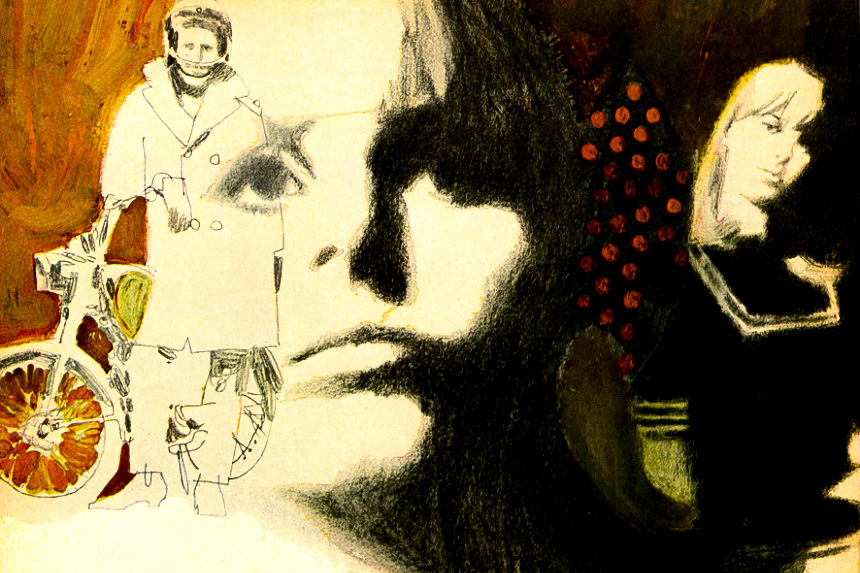

Kentuckian James Baker Hall was the state’s Poet Laureate in 2001 at the tail end of his career as a writer and photographer. For his short stories, he won the Pushcart Prize and the O. Henry Prize. The latter came for his 1967 story, “A Kind of Savage,” published in the Post. The witty take on sixties campus life depicts a traditional school for girls shaken by a troublemaker Freshman with a taste for jazz and bearded Communists.

Published on February 11, 1967

For the second time in three weeks the housemother from Brewster Hall, Elizabeth Dickinson, class of ’29, was sitting in the Dean’s office yacking on and on about this girl from Lexington, Kentucky, who was going to wreck the entire dorm if something wasn’t done. Knowing Elizabeth (dear old Elizabeth), the Dean halved everything she said and discounted the tone completely — which left little that could be construed as a dean’s business. Courtney Pettit this, Courtney Pettit that! For lack of any other way to entertain herself, Dean Bradford leaned forward in her chair in a private parody of interest and attention.

Elizabeth Dickinson was a frail, nervous woman who whipped lickety-split along the campus walks with her head buried on her chest; every few yards her face would pop up, smiling, only to disappear again abruptly. For a while the Dean had thought that the housemother had a tic rather than any real interest in the world, but Elizabeth Dickinson knew as much about what was going on at Talcott College, from the lowest freshman right up through the President, as anyone around. The Dean often thought now that if you could draw her hair back while she was trotting along with her head down, you would find her ears standing at alert like a dog’s. It wasn’t simply Elizabeth Dickinson, class of ‘29, that brought out that sort of meanness in the Dean; it was Elizabeth Dickinson as one of many. They were like the Chinese Communists, these old alumnae still attached to the college; what they lacked in equipment they made up for in dedication and tactics and sheer number — they just kept coming in human waves. A whole squad of them operated out of the very place where the Dean lived and ate, and one or two evenings of every week she fled straight from her office into New Haven; it was either that or end up being insulting. Or, worse still, dead.

“If you and the girls can’t handle something like this, what can you handle, Elizabeth?” the Dean said. “I don’t know this Pettit girl nearly as well as you do, of course, but she impressed me as a very quiet and accommodating little girl.”

“That’s the way she impressed me! That’s the way she impresses everybody!”

What the housemother didn’t understand, what very few of the little old ladies around Talcott College understood, was that the refinements and distinctions that meant so much to them were largely lost on the girls, who saw you as either for them or against them; either you were on the side of life, of freedom and adventure, or you were some version of death itself. If they ever got the idea that you were an old maid, you’d had it as an influence in their lives. Not too many years ago Dean Bradford would have tried to get Elizabeth Dickinson to see that, but now she knew better than to try. Considering the sort of women that Talcott was trying to cultivate, and the personnel they had to do it with (on paper, half the faculty was male, but it was hard to tell sometimes which half), the Dean was inclined to marvel at what success the college had.

Before the appointment was over, the Dean was feeling sorry for Elizabeth and a little guilty about being unable to take her problems more seriously. By way of making amends, she invited herself over for a drink late that afternoon. She thought it was clear that this would be a purely social call, but the housemother misconstrued the whole thing; when the Dean arrived, expecting to flop down in a chair with a drink, there in the living room were three of Elizabeth’s girls — Courtney’s ex-roommate, the dorm president, and the chairman of the dorm discipline committee — and the Dean found herself listening to the same garbage she’d heard that morning. Courtney Pettit this, Courtney Pettit that, all over again. Somebody was always having to get up and let her in after the doors were locked; she stayed up all night and slept all day and never seemed to study; penalizing her with extra duties simply meant risking further humiliation because it was hard enough getting her to do her own share in the first place. It all struck the Dean as enough to make you fall in love with Courtney Pettit, sight unseen.

The girls left, and as she was having her drink with Elizabeth, she said, “What’s this I hear about you hanging out your laundry on Miss Finch’s lawn?”

The housemother, taking her ritual walk about the campus on a recent Sunday morning, had discovered two undergarments — one male, one female — tied to the branch of a tree on the President’s lawn.

“What?” Elizabeth exclaimed. “Where in the world did you hear that?”

“From Miss Finch herself. She said she happened to look out of the window, and there you were hanging things out to dry on her trees.”

“I was taking them down! Lord have mercy, I — Oh, you had me scared to death!” The housemother, blushing, shook her head in bewilderment at the Dean’s imagination. “No wonder the girls love you.”

“I thought they were scared of me.”

“Oh, underneath it all they love you. Dearly! You’re really so young at heart. They identify with you.”

“Let me catch one doing that! I haven’t got a heart, Elizabeth, just a gizzard.”

On the way home she grew conscience-stricken for having abused the poor timid woman all over again. Unlike some of the little old ladies on the faculty, Elizabeth Dickinson had no say in the college, so she was relatively harmless; what’s more, compared with most of the old maids that the Dean was obliged to deal with day in and day out, Elizabeth was open and lively. That was cutting it pretty thin, aligning Elizabeth Dickinson with the life force, but as the girls would tell you, you had to get your kicks where you found them, and in a woman’s college you could end up sometimes cutting things pretty thin.

The Dean had nothing against the college or her job that being able to get away from it every night wouldn’t have relieved — or so she was fond of telling herself. When she’d first come there, after the war (she and Miss Finch had been in the Marines together, a fact that still set everybody — students, faculty, alumnae — off in seventeen different directions at once), she’d promised herself, even told Miss Finch, that if she wasn’t allowed to live in New Haven after a time, she would find herself another job. That was a good many years ago, and she’d never mentioned it again. For one thing, she found the way of life on campus much less sterile and parochial than she’d imagined. It was, in fact, very lively in a quiet way — the lake, the arboretum, the library, the talk — and she’d found it possible to live a deeply civilized life. Still, she would probably have moved to New Haven long ago but for the fact that more and more of the young faculty, especially the men, were trying to do that. The administration had not been forced to draw the line yet, but Miss Finch had gone out of her way on numerous occasions to let it be known that she didn’t intend trying to run a residential college with a commuting faculty. If the Dean hadn’t been a dean, she would have gone ahead anyhow, knowing that quite a few others were getting by with it, but being in the administration carried a special burden in the matter, as in so many others.

A lot of people were saying that Courtney Pettit would never fit in. that she was the most egregious mistake Talcott College had made in years, but when the Dean finally did agree to call Courtney in, it was more from curiosity than concern.

She was all prepared, when Courtney came in, for another of those full-dress debates in which the college was accused of being an oppressive reactionary matriarchy, but Courtney showed no interest in representing the forces of life and freedom. She was the first to point out that Talcott College was Talcott College, that she had known more or less what she was getting into when she came, and that she could always leave if she didn’t like it. It was like interviewing a Girl Scout with bad grades, not a chick who was feared to have revolution in her blood.

“Gosh, Miss Bradford,” Courtney said. “I try, I really do.”

“What’s so immensely difficult about obeying a few simple rules?”

“It’s terrible, I know.”

“You haven’t been to English in three weeks. How long do you think you can keep your grades up without attending classes?”

“Probably not even one more day. I’ve been lucky on all those English papers.”

“Why didn’t you wait on tables the other morning when you were supposed to? Now don’t give me that stuff about how ashamed you are. I want the reasons — one, two, three.”

“I was in bed.”

“My dear child, we were all in bed until we got up. Did it ever occur to you that if you came back to the dorm on time and went to bed at some decent hour, you wouldn’t be so sleepy?”

“Yes ma’am, I know it. I’ve tried to go to bed early, but I always end up just lying there wide awake for hours and hours. I reckon it’s my metabolism.”

“Your metabolism, huh?”

“Oh, don’t make fun of me, Miss Bradford. It’s the truth, it really is!”

“You’re driving Miss Dickinson to distraction, I trust you realize that.”

“Yes ma’am.”

There was a long silence.

“Well? Is that a matter of indifference to you?”

“No ma’am. I’m sorry about Miss Dickinson. I realize she has a hard time.”

The Dean looked up sharply. “What do you mean by that?”

“Nothing,” Courtney said. “Heavensakes, I don’t have anything against Miss Dickinson or any of the girls, I really don’t.”

“Either you’re going to learn how to get along in the dorm, or you’re going to end up before the Student Council. Do you understand what that means? It’s up to you.”

“Yes ma’am, I know it,” Courtney said. “I’m going to get a good night’s sleep tonight and start working off all those penalties tomorrow.”

She waited on tables three times a day all that week, and when Elizabeth Dickinson called, wanting to know what in the world the Dean had done, the Dean was tempted to suggest that Courtney Pettit, far from being disrespectful of authority, understood and appreciated it quite well, because she responded only to the real thing; but instead, a little ashamed of the frequency with which she used housemothers and virgin girls to take an attractive measure of herself, she told Elizabeth simply that she’d done her bit and the whole thing was now back in the laps of the powers at Brewster Hall, where it should have stayed all along.

At the dorm, though, few believed that Courtney Pettit really wanted to reform, and the first time she didn’t show up for breakfast duty, they were laying for her. The word spread over the dining room like news of an international crisis, leaving silence in its wake. The girls turned their chairs away from the tables; the waitresses. wearing their aprons like placards, lined up against the wall in protest; everybody trained attention on the door, waiting for the delinquent Courtney. A few girls got their own breakfasts, boycotting the protest, but the rest just sat indignantly, refusing to take a bite until Courtney Pettit reported for duty. They waited five minutes. Ten. Fifteen. They couldn’t sit around waiting all morning — most of them had an eight o’clock class — so they hastily assembled an ad hoc committee to roust Courtney out of bed. The five girls boarded the elevator and waited in grim silence, like a bunch of Marines in a landing barge, until someone pushed the button. When the committee got back, somebody pointed out that it was no good getting Courtney up because they had no way to keep her from going back to bed again. Somebody else suggested that getting Courtney Pettit to fulfill her responsibilities was considerably more trouble than it was worth, and that the reasonable thing was for them to go on about their business as though she didn’t exist. Somebody else pointed out that, yes, that was true, and it was probably exactly what Courtney was counting on; she was putting them on no matter which way they turned. A senior jumped up to say that she had taken as much guff off a freshman as she intended to take, that she personally had served that little bitch her meals a half dozen times and would be damned if she would let her get out of New England without paying her debts; there was nothing personal about it, it was a matter of social justice. With that the whole dining room exploded into factions, and the upshot was that most of the girls had to go without breakfast in order to make their classes.

It was midwinter before the Student Council got anywhere near as worked up as the girls from Brewster Hall. The first time they called Courtney in they contented themselves with reviewing the trouble she’d caused and issuing rather severe warnings about what would happen if she persisted in thinking she was a law unto herself. Courtney was contrite, and left quite obviously chastened. Some of the Council members were seeing her for the first time, and they agreed afterward, despite the loud protests of the representative from Brewster, that anybody who could be upset by that little girl was looking for somebody to be upset by. “Just wait,” the Brewster girl kept saying, “just wait and you’ll see,” and the more she said it the more fun they made of her.

For several weeks Courtney behaved herself, but then all of a sudden everything was right back where it had started, and this time the Council decided to confine her to the campus on weekends for a month. For the first time since Courtney had taken up residence in Brewster Hall the girls listened without complaint, at least on the weekends, to the jazz she played all night in her room. In fact, some of the more vindictive made a ritual of going to her door at date time on Friday and Saturday and Sunday nights and yoo-hooing good-bye to her. Everybody, Courtney very much included, seemed more or less satisfied that she’d gotten what she deserved, until she was seen in New Haven late the last of those Saturday nights — while back at the dorm the housemother and the Student Council representative, among others, were listening to all that jazz. A quick investigation revealed the possibility that Courtney had been taking her privileges all along, but it couldn’t be proved, and so the Council, influenced again by Courtney’s disavowals and pleas and resolutions, only repeated the original punishment. This time there was no jazz at all; in fact, in a touchingly conspicuous effort to overcome suspicion, Courtney kept out in the open in the library virtually every night until it closed. But then, with even the more skeptical admitting it was unlikely that she would try to pull anything now, she was seen in New Haven again, eating breakfast one Sunday morning with a bearded fellow, and the Student Council called a special meeting to lower the boom. Before long they had her confined to her room night and day, seven days a week, except for classes — at least on paper they had her confined to her room — and the entire college was up in arms. The editor of the paper put the student government on the spot by pointing out what everybody was becoming more and more aware of — the Council had no power that couldn’t be ignored by each and every student. One group within the Council wanted to salvage what prestige it could by trying to cultivate Courtney’s impulse to reform, another wanted to pursue the hard line with ultimatums that even they weren’t sure they could enforce. Finally, in frustration, the Council made an unprecedented request that the administration take Courtney Pettit off their hands.

“What choice have we got?” the President asked the Dean. “The girls have done all they can do.”

“What about allowing the Council to recommend probation or expulsion? It would give them at least the semblance of some real power.”

There was a long silence at Miss Finch’s end of the phone.

“Subject to the approval of the faculty adviser or something like that,” the Dean added.

Finally, Miss Finch said, “No, that could end up getting us all in a lot of trouble. I don’t think we ought to encourage them to think they’ve got anything to say about that at all. What is it about this girl anyway? You’re fond of her, aren’t you?”

“She’s tremendously entertaining,” the Dean said. “More than that, actually: she doesn’t for a minute expect or even want the college to underwrite her behavior. It’s extraordinary. I haven’t seen a girl like that in all my years here.

She can give a more intelligent and eloquent defense of the way things are around here than some of those Westchester girls on the Council. Their trouble is, they think they’d be immensely better off if they could get rid of Courtney Pettit, when the truth of the matter is that they’d have to invent her if she didn’t exist.”

“Does she want to be expelled? Is she just leading everybody on?”

“If she were a little older I’d be inclined to think maybe she was one of the world’s great straight-faced comedians, but I really doubt it now. You know how kids that age are: there are probably three or four mutually exclusive Courtney Pettits crashing around inside that girl, and whenever one gets on top for any length of time, there’s bound to be a palace revolution. She’s like the wolfman — about once a month the Talcott gentility and respectability has a full-moon effect on her; it turns her into a kind of savage. It’s an adolescent response to the same damn conflict that produces people like … ” The Dean named several of the more publicly tortured and convoluted personalities around the college.

“Look,” Miss Finch said, “you go ahead and handle it in whatever way you see fit. Just keep me posted. If we’re going to let somebody wreck the college for the sake of being entertained, I don’t want to miss any of it.”

“I’m not going to let her go too far, don’t worry about that.”

When she put the phone down, the Dean began dictating a note requesting Courtney to make an appearance tomorrow at eleven, but then she grew impatient with all that formality and told her secretary to get the girl on the phone. And when Courtney came in the next morning, the Dean laid it on the line: She was going to have one more chance to respect the authority of the Council; after that she’d find herself confronted with the administration. By way of dramatizing that she meant every word she said, the Dean announced that there would be another meeting of the Council, and that she personally would be there, in the role of an observer.

“Well, how about it?” she asked.

“Gee whiz,” Courtney said. “If I have to meet with those mixed-up girls many more times I’ll go out of my mind.”

After Courtney left, the Dean thought of calling Miss Finch to share that remark with her, but chickened out at the last minute. She tried to think of somebody she could call; there were plenty of people around who would appreciate what Courtney had said, but none that she could phone for just that. Finally, she buzzed for her secretary.

The typing stopped, and the secretary appeared in the doorway, her glasses in her hand. “Did you want me?” Just the sight of her, another stolid well-meaning old lady for whom the college was life, suddenly moved the Dean.

“Guess what I told Miss Finch when she told me to have another talk with that Pettit girl.”

The secretary confessed that she couldn’t guess.

“I told her,” the Dean said, “that if I had to meet with that mixed-up girl many more times I’d go out of my mind.”

“You know,” the secretary said solemnly, “just to talk to that girl, you’d never know she was that way. All these girls running around in sweat shirts and blue jeans, they’re the ones who don’t go to chapel.”

The Council put off the meeting for a week in order to prepare for it; despite the Dean’s disclaimers, they believed they were being called on to show cause why the case should be taken to the administration, and they weren’t about to be made fools of again.

The meeting, when it came, was a solemn occasion. The Council president sat at one end of the great oval table and Courtney at the other, linked by girls around both sides, many with manila folders before them. One girl submitted the fact that, according to certain reliable sources at Yale, Courtney’s bearded boyfriend in New Haven was a Communist. Another girl (the head of the campus chapter of Young Americans for Freedom, a girl who was fond of calling William F. Buckley Jr. “Bill” and of knowing exactly what he was up to whenever the fuzzy-headed liberals said he was up to no good) brought up the subject of what her father would think of Talcott College for condoning “a girl like that.” Obviously no one at the table thought for a minute that Courtney had stayed out all night with a bearded Communist to eat ice cream at Ho Jo’s, but all of them saw the need to stick to matters that were their business and to accusations that could be proved if necessary.

“Every girl on this campus takes the honor of the college with her wherever she goes,” the first girl said. “She’s desecrating us all! She’s desecrating you, and you, and you” — she went around the room — “she’s desecrating Dean Bradford, she’s desecrating me!” She subsided into an emotional silence, her hand pressed to her chest.

“Courtney?” the Council president said.

“Gee,” Courtney said, “I hadn’t thought of it that way.”

“Do you understand how we feel?”

“You mean ‘desecrated’?”

“I mean, do you understand or don’t you!”

“It’s not a question of her understanding it,” the first girl said. “Any degenerate can understand it. It’s a question of whether she respects it!”

“Golly,” Courtney said. “I can’t respect desecration — that’s sick. Desecration gives me the willies.”

“That’s not what I mean!”

“How am I going to keep somebody like you from feeling desecrated?” Courtney wanted to know. “If you feel desecrated, that’s your problem, huh? Not mine. When it comes to feeling desecrated, it’s every man for himself.”

That did it. Up until then the proceedings had been fairly orderly, partly for the Dean’s sake and partly out of the girls’ recognition of the fact that things could easily get ugly if they weren’t careful, but that last insolence loosed the hounds in them: They accused Courtney of being a dirty, drunken little slut. What they had been advertising as moral indignation was suddenly revealed to be nothing but hatred posing as righteousness. The Dean, assuming that Courtney was unaffected, that she would sit it out calmly and shame them all, was embarrassed for the girls and for herself too. She was about to leave the room, as a way of registering her protest and bringing the girls back to their senses, when the whole business took an abrupt turn.

Suddenly everybody was staring at the girl sitting there at the end of the oversized table, the fingers of both hands hooked over the edge. Courtney wasn’t looking at anyone; she was just staring straight ahead, her round, innocent eyes sorrowful and hurt. She was close to tears.

“I try,” she said, shaking her head, “I really do. I try as hard as I can. I don’t want to cause trouble, I really don’t.”

No one knew what to say.

Finally, the Council president pointed out that people had to be judged finally by what they did, not by what they intended to do. No girl there in that room had been admitted to Talcott College just because she’d tried hard, and no one would be graduated, no matter how hard she tried, unless she met certain objective requirements. It was just the right tone, conciliatory without being soft, apologetic without compromising the hard justice of the Council’s position. All the girls nodded with relief and pride.

Then someone wanted to know, well, where did they stand? At which point, again to everyone’s surprise, Courtney got out a typewritten statement and read it. No one, not even the Dean, doubted for a minute that she meant what she was saying. She spoke of the fall colors around the lake, the red and yellow and orange of sumac and maple, and of the fallen leaves scattered across the lawns and paths and parking lots; she called to mind the sound of the chapel bells, and the view of the lakeside tennis courts from the path up the hill; she spoke of the great rambunctious Brueghel scenes at dusk on a bitter winter day, when the frozen lake was crowded with skaters and dogs and racing children with hockey sticks; she spoke of the common rooms where some barefoot girl in a robe was forever ironing, of the long bull sessions with girls wandering in for a while and then back out again, of the transformation every weekend of teenagers into chic young women in heels; she spoke of snow-plows clearing the campus roads late at night, of the look of the lighted dorms on the snowy hillsides around the quad, of the couples courting outside those dorms just before the doors were locked, of the concerts, the plays, the readings, the lectures; she spoke of girls sunbathing on the roofs in spring, of the redwing blackbirds singing in the field below the gym, of the boys coming in from Yale and Wesleyan and Princeton and Amherst and colleges all over New England.

In closing she read the Donne passage about how no man is an island unto himself but each a part of the main, and when she finished the room was absolutely silent again. The Dean found herself deeply moved.

The Council president looked slowly around the room. “I don’t think anything more needs to be said.”

“I don’t think anything more could be,” someone said.

For several weeks the Dean waited for something to happen, but nothing did. She wasn’t particularly comfortable with the idea that Courtney was on her way to becoming a thorough- bred Talcott girl, but it had happened before and no doubt would again. In time even Elizabeth Dickinson went on record as giving the girl a chance to grow up and become civilized. The Dean was about ready to chalk up another one for good old Talcott College when she got a note from the Dean of one of the sister colleges saying that she ought to know that some girl at Talcott, claiming to have the name and address of the greatest lover in France, was trying to organize a summer pilgrimage composed of one girl from each of the sister colleges.

And the very next Saturday, Courtney stayed out all night without signing out, and didn’t return until a little before nine the next morning. The girls were pouring out of the dorms on their way to church when a bright red sports car, driven by a bearded man and followed by four motor scooters. idled in, deposited Courtney unceremoniously in front of Brewster. and idled back out again, the string of scooters wagging behind the sports car like a tired tail. The doors of the dormitory were wide open, but Courtney, who was still drunk, stood on the stone wall around the beech tree demanding to be let in. “Open up!” she kept shouting, as though it were late at night and the place locked up tight. “Open up!” Then she jumped off the wall, climbed into the housemother’s car, which was parked near the door, and started blowing the horn, stiff-arming it with both hands. Before long every girl in the dorm was downstairs and out on the sidewalk. They had to wrestle Courtney inside and onto the elevator. Poor Elizabeth Dickinson spent the rest of the day under sedatives.

The next morning the Dean scotched all formalities and dialed Courtney’s number herself. The phone rang and rang, but no one answered. The Dean sat there, elbows on the desk, and waited. There was something exhilarating in the fact that Courtney hadn’t become a Talcott girl after all, but it was the sort of feeling she knew she couldn’t indulge. Finally, Courtney picked up the phone.

“Courtney?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Dean Bradford.”

“Yes ma’am.”

Silence.

“Your metabolism is rather sluggish today. I’ve been ringing for five minutes.”

“Yes ma’am, you know, I heard something ringing, but I thought it was the alarm.”

“It is the alarm, my dear.” The Dean paused, but nothing came over the phone except Courtney’s breathing.

“Can’t you say anything but ‘Yes ma’am’?”

“Yes ma’am. I mean, no ma’am.” Courtney laughed. “Sometimes I reckon I just don’t know what it is people want me to say.”

“What does that mean?”

“Well, sometimes I just don’t know what you-all want.”

You-all, huh? The Dean stalled for as long as she dared, hunting for an oblique way to distinguish herself from Elizabeth Dickinson and the Talcott girls, but she knew that Courtney had her.

“What we-all want, my dear, is for you to abide by the rules. That’s all, I can assure you.”

There was a long silence, by which Courtney managed to insinuate — or so it seemed to the Dean — that she knew that was a lot of guff, and that the Dean knew it too.

“I’ll give you an hour to get dressed and get over here, Courtney. If you’re not here in an hour — don’t come.”

By the time the girl arrived, the Dean had spoken with her parents, with Miss Finch, and with the housemother. Campus life could no longer tolerate Courtney (even the girl’s father wanted her expelled), but the Dean, despite her own qualms, finally persuaded everybody that Courtney should be allowed to finish out the few remaining weeks of the year by living, under dormitory rules, with an uncle in New Haven.

The poor uncle was an elderly lawyer who had seen her no more than a dozen times in his life — one day he and his wife were living the perfectly civilized life of a New England couple of means, and the next Courtney Pettit was in residence. The rules were hard enough for the Talcott people themselves to understand, so it was no wonder he found them utterly confusing. Almost every day either he or his wife phoned to check Courtney’s interpretations with the Dean’s office.

The weekday eleven o’clock check-in, did that mean the girls had to be in their rooms or merely on the premises? He was asking because Courtney had sat in a car out in front of the house the previous night from eleven until nearly one A.M. No, the Dean said, eleven o’clock meant in the house with the doors locked. So the next night Courtney brought her New Haven friends in with her, five of them with three guitars. Neither he nor his wife had anything against young people having a good time, the uncle told the Dean, but he felt obliged to see that Courtney kept her part of the bargain, and he was beginning to suspect that she was taking advantage of his lack of familiarity with the rules. He hoped he wasn’t being merely old-fashioned, but to be quite frank neither he nor his wife found much to appreciate in the young people she was bringing into their house — they certainly weren’t the sort one would expect a Talcott girl to be running around with. A few days later he called the Dean the first thing in the morning and said that if that girl wasn’t out of his house by dinner time, he was going to call her father to come after her.

The Dean got Courtney out of class to the phone.

“Guess who.”

“Dean Bradford?”

“Guess what.”

“I’ve had it,” Courtney said.

“You said it, honey.”

“What’s the matter now?”

“You’re attending classes at Talcott College, and you’re no longer a student here. that’s what’s the matter.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

“Gee.”

A long silence. Did Courtney honestly not care? Hard as it was for her to face, the Dean was afraid that this girl was insisting on their differences, and she felt betrayed. She knew that when it was all over, when she was left with those who cared about nothing else, that she would want Courtney not to have cared at all, that she would be drawn to the idea that there was somebody out there in the world who appreciated everything that Talcott had to offer and was still able to toss it all away with ease. Now, though, there was something in the Dean that wanted to see a little chink in the girl’s armor. “How’s the pilgrimage to France shaping up?”

“How did you find out about that?”

“I just assumed that’s what you’d be doing this summer.”

Courtney laughed appreciatively. “It’s falling through. I’ve got a Cliffy and a girl from Barnard, but the others aren’t coming through. Everybody over at Vassar is shook about the school’s reputation. I haven’t heard a word from Smith — are there people still sort of moving around and breathing over there at Smith?”

“Some, sort of,” the Dean said.

Another silence.

“Your bearded Communist boyfriend, don’t you think that’s going just a bit far? I mean aesthetically? You disappoint me at times, Courtney.”

“He’s not a Communist, Miss Bradford.”

Okay, so he wasn’t a Communist. She ought to have known — another point for Courtney Pettit.

“I suppose you were just too ashamed to admit it, though.”

Courtney laughed again, and the Dean found herself responding to the girl’s appreciation.

“I went out on a limb for you, I trust you realize that.”

“Yes ma’am, I know you did.”

A pause.

“Do you want to come over here and talk about it? There’s nothing that can be done, but we can talk about it.” The minute she’d said that, she was sorry.

“I will if you want me to,” Courtney said.

A long silence this time.

The Dean was suddenly disgusted with her own naïveté and weakness. “Forget it,” she said. “Just get the hell out of here, will you? I don’t want to see you around here after today, do you understand?”

“Yes ma’am.”

Late that afternoon, Elizabeth Dickinson telephoned to find out what had happened, and as the Dean sat there at her desk listening to the housemother go on about the whole affair, she saw three girls pull off their shoes and walk across the lawn outside her window, dragging their feet sensually through the grass. Suddenly they tossed their books to the ground and raced up the long steep terrace, laughing and screaming, slowing as they approached the top, pulling their long shadows, until they were barely moving. Then, like stunt planes peeling off, they angled along the ridge of the terrace for a few yards, picking up speed again, and then they dove to the ground, one behind the other, and let themselves go, rolling like logs back down the hill. Their laughter rang out in the clear spring air; along the campus walks girls stopped and smiled and hugged their books and watched. Down they came, faster and faster, their supple bodies spinning through the lush grass, their skirts and blouses and legs and arms and hair a blur of freewheeling light on the green hillside. Unconsciously, the Dean lowered the phone against her neck, pressing Elizabeth Dickinson’s voice out of hearing for the moment, and held her breath — held it for the girls’ safety, for the sheer beauty of the life that was in them.

Elizabeth Dickinson said, “You know, there are some people who just don’t appreciate Talcott College, and they just don’t belong here — it’s as simple as that.”

“Maybe you’re right.” the Dean said. Why was it she couldn’t acknowledge the claims those girls out there had on her without getting involved with the likes of Courtney Pettit? Sometimes her life seemed to be nothing but a crude mockery of the distinctions her mind lived on. “But nothing’s as simple as that,” she said to Elizabeth.

One drink that evening before dinner and she knew that she couldn’t face the little old ladies in the dining room, so she just sat there in front of her TV in a kind of stupor, eating blue cheese and crackers and drinking bourbon. After a while she dozed off, woke, and struggled into the bedroom. Several minutes later she found herself sitting on the side of the bed with her shoes and stockings off and her blouse unbuttoned, but she couldn’t figure out whether she was supposed to be dressing or undressing.

The phone rang, piercing her stupor. It was Miss Forman, the head of Physical Education, calling from the next apartment house. She needed the Dean’s help with a little problem. The matron over at the gym had just phoned to say that the new young man in English, Mr. Klein. had played squash with a friend during the dinner hour and hadn’t returned the squash-courts key. Since Mr. Klein was just across the hall there from the Dean, Miss Forman wondered if she would mind inquiring about the key. Why, of course the Dean said, she’d be glad to. As it turned out, Mr. Klein hadn’t pocketed the key — how could he? he said; it was wired to an old Ping-Pong paddle — he had left it, not at the matron’s window, but around the corner on her desk, where he’d assumed it was conspicuous enough. The Dean phoned the information to Miss Forman and, though it was still early, went to bed.

It wasn’t until the next morning that it hit her just how odd the whole business about the key really was. In the first place, what the dickens were they locking the squash courts for? Bravado? In the second place, with all the duplicate keys around, surely there was no immediate need to recover the one Mr. Klein had used — they were just antsy at the idea of a man (a new young man at that!) running off with a key to something they’d locked up. And even if they’d needed that particular key that very night, and been reasonable in suspecting that someone had run off with it, paddle and all, why had the matron called Miss Forman instead of Mr. Klein himself? And why had Miss Forman. instead of contacting Mr. Klein directly, carried the matron’s foolishness just that much farther? And worse still, the Dean thought, what about herself? What really shook her up wasn’t that she’d gone along with the whole silly thing, but that she hadn’t seen anything silly about it. It had seemed a perfectly natural little problem being solved in a perfectly natural way — if a man runs off with one of your keys, then naturally you’ve got to get it back immediately, and naturally you can’t just ask him for it. One doesn’t go around insulting people, even when they do behave suspiciously! The Dean tried to make allowances for herself — she’d been drinking, hadn’t she? — but she’d destroyed that excuse too many times in dealing with the girls. The real trouble, of course, was that all of it was perfectly natural — natural to the little old ladies at Talcott College.

The next morning, before she had a chance to change her mind, the Dean took an apartment in New Haven and informed the housing office that she was moving out; that afternoon she left her office early and loaded the back seat of her car with her belongings. If she got fired, well then she would just have to get fired, for it seemed clearly a matter of life and death to get some distance between herself and the college.

As she was waiting at the gate for a break in the rush hour traffic, a horn beeped, and there behind her in a sleek little red sports car with the top down were Courtney Pettit and her bearded boyfriend. The Dean’s heart jumped. Her eyes met Courtney’s in the rear-view mirror, and they both smiled politely, the smiles growing steadily richer until, in unison, they burst out laughing. The moment was shattered, though, when the horn beeped again, this time with unmistakable mockery, telling her to move out or move over. The Dean’s smile vanished, but Courtney only laughed that much harder. What they would infer from her loaded car the Dean didn’t know, but she felt revealed before them, as though they were seeing something that she did not want them, of all people, to see. If they tooted that horn again, she would scream! No. she would just sit there, by God. until they quieted down, and then she would — Suddenly they swung out behind her, and with Courtney’s head flung back in laughter, proceeded to show her how it was done. The Dean had been thinking that she would get out and walk back there calmly and say that maybe they weren’t intimidated by rush-hour drivers, but she was just a hung-up Talcott lady herself and there was no telling how soon she would find her way into that kind of traffic — and then they shot around her, bluffed their way recklessly in, and roared off toward New Haven, trailing Courtney’s laughter like tin cans behind a marriage car, leaving her there alone at the college gate.

Featured image: Illustration by Mark English / SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now