When it comes to controversial Supreme Court decisions, Plessy v. Ferguson remains a flashpoint. The 1896 decision perpetuated segregation if the transportation or facility in question was “equal” in quality to the thing that was serving the white population. Of course, the facilities in question were rarely equal in quality, design, or funding. In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education smashed that notion in a decision that rendered segregation of public schools to be unconstitutional. However, two cases decided in 1950 laid the groundwork for Brown by challenging “separate but equal” in higher education. Those cases were Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, and their decisions were returned 70 years ago today.

Sweatt v. Painter involved Herman Marion Sweatt. Sweatt, who was black, applied to the University of Texas School of Law, but was denied admission. The rationale handed down by the University president Theophilus Painter was that the constitution of the state of Texas banned integrated education. Sweatt’s original suit received a continuation in state district court, which was a stall tactic for the school. The University of Texas then put together a law school in Houston for black students, which wasn’t even in the same city (Austin) as the original School of Law. With the support of the NAACP, Sweatt took the case to federal court on the grounds that the facilities, while separate, were in no way equal.

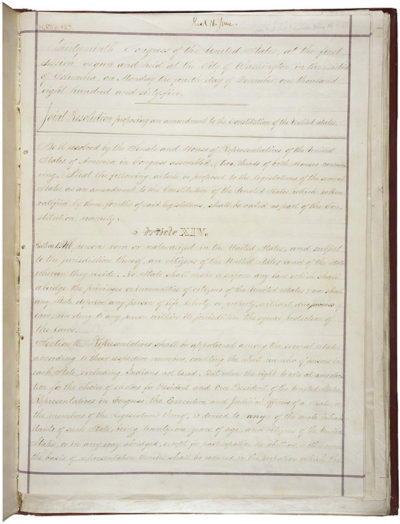

The Supreme Court decided in favor of Sweatt, agreeing that the facilities created for black students suffered greatly in comparison. Examples in the unanimous decision included the smaller number of faculty, the vast disparity in library size, and a variety of other facilities issues. The Court also cited the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment as the constitutional basis upon which Sweatt should be admitted.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents involved graduate programs at the University of Oklahoma. George W. McLaurin had earned a Master’s in Education from University of Kansas, but was denied the opportunity to pursue his Doctorate at Oklahoma. McLaurin sued in U.S. District Court, invoking the 14th Amendment, and won. The school admitted him, but forced him into separate facilities, even occasionally making him eat at times when white students weren’t present. McLaurin petitioned the District Court for redress, but was denied, so he took the case to the Supreme Court. In another unanimous decision that also leaned on the 14th Amendment, the Court held that the school couldn’t restrict McLaurin in that manner.

The two cases set the stage for Brown v. Board of Education four years later. Another influential case leading up to Brown was Mendez v. Westminster, which allowed the integration of Mexican-American students into the California school system. The Supreme Court Justices deciding on Brown would also invoke the 14th Amendment and unanimously vote to overturn the “separate but equal” notion that had been enshrined in Plessy.

Sweatt and McLaurin may not be as widely known, but they remain significant steps along the way toward realizing an equal vision of education in America. They set important precedents that allowed bigger decisions to be made later. 70 years on, in an America that still struggles mightily with a legacy of segregation and mistreatment, it’s important to acknowledge that the smaller victories can still bring about greater triumphs.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now