Oma Almona Davies was a regular contributor to The Saturday Evening Post throughout the 1920’s. For “A Ring With Rubies At”, we find her collaborating with the iconic post illustrator Tony Sarg to tell a story of romance, robbery, and danger, all centered around a magazine advertisement similar to those found in the Post at the time.

Published on May 10, 1924

Elisha Maice was on his way to kill the Hepple girl. His thoughts were as fiery as his hair, as deep as his blue, green-flecked eyes, as purposeful as the forward jut of his chin.

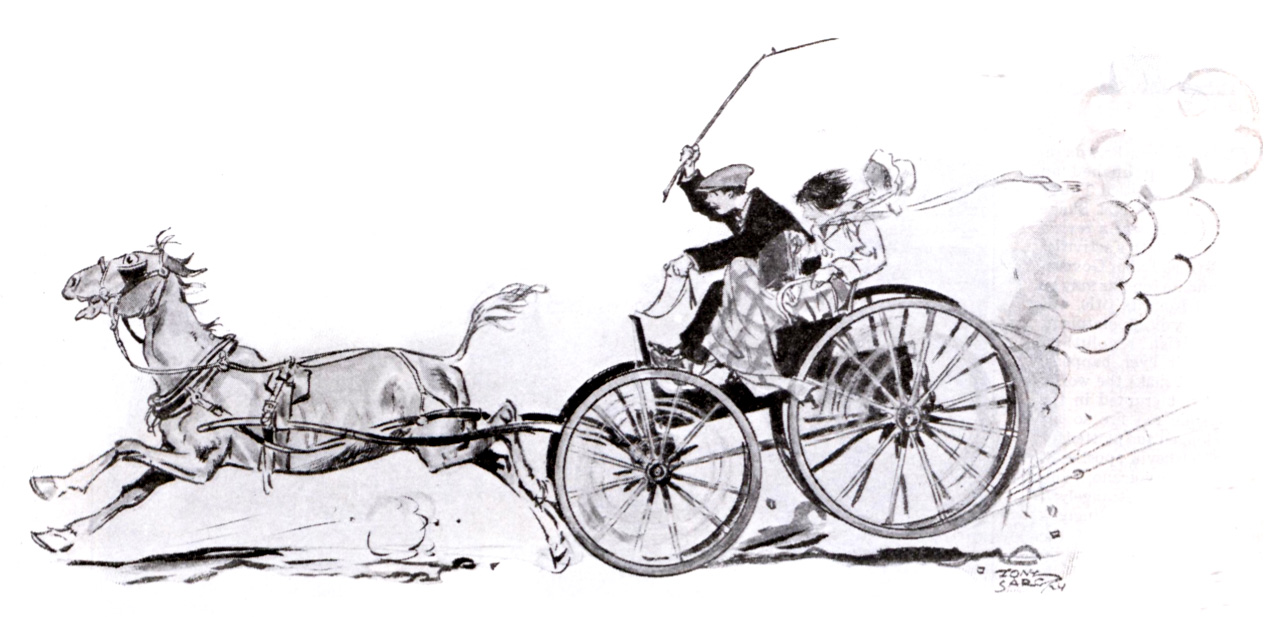

In amorphous hunch upon the seat of the top buggy, he pestered the horse’s rump with an ineffectual peach shoot while he passionately reviewed the previous half hour of his history. The galling thing was, of course, that he had been yanked upward by the neck scruff at the momentous instant in which he had decided his financial destiny.

For there he had been, a half hour before, with elbows taut upon the warm kitchen table, a 15-year-old man with twelve dollars and seventy-five cents banked in canvas bag upon his bosom, in travail as to whether he would become a cattle king or a hog baron. There had he been when he had rendered final decision in favor of the barony, the superior eagerness of the hog tribe to reproduce its own being the unanswerable argument in its favor. It had been at that climactic moment that Adam had leaped in, ox goad in fist, eyes wild.

“The bull’s outbusted the hind fence! You got to make me an errant. Make quick now!”

And as the potential baron, with hogs teeming by the thousand about him, had sat staring, he had been dragged from his chair, hoisted across the freezing ruts of the barnyard and dumped over the wheel into the top buggy.

“You got to git my girl from Schindler’s to Hoopstetter’s! Make hurry quick! And you fix a dates fur me — you tell her I’m a-settin’ up Saturday night agin!”

Oh, Elisha had protested at mention of the Hepple girl of course! He had started to kick out of the buggy. But Adam had plastered his eighteen-year spread of hand against Elisha’s middle and had pasted him against the seat again.

“Dast you! And you take good care to my girl or I’ll — ” And then, because he was Adam, and Elisha’s mother as well as his brother, he had grinned, rammed a huge paw into his pocket and had flung a dime upon the buggy seat. Then he had run, gripping his ox goad and hallooing to their father, who was already lunging toward the far end of the field.

In the clear flame of his anger against Adam, the bull and the Hepple girl, Elisha saw the problem of his life distinctly. His problem was to put into word and into action the fact that he was a man. Never before had he objected to being Adam’s younger brother — being anything to Adam had been enough. But now that he was being dragged into entangling alliances with Adam’s sticky girls, the relationship, as such, must cease

Here he was on his way — on Adam’s way — to the Hepple girl. He had to get her from her Schindler uncle in the village to her Hoopstetter uncle in the country. Why couldn’t Adam have let Schindler get her to Hoopstetter? And, back of all that, what did she want to come visiting around Buthouse County for anyway? If she was in a factory in the city, why didn’t she stay factor-ing then?

A groan escaped him as he beheld the red top of the Schindler house above its fir hedge.

From Schindlers of assorted sizes and sexes who swarmed into the side yard emerged finally the Hepple girl. She was supported toward the vehicle by a slender male Schindler with thin damp-looking hair. Supported is a carelessly chosen word, however; the young man’s legs seemed scarcely adequate to support his own frame — they gave the impression of being just on the point of swaying from beneath him. He nested his twiglike fingers about the girl’s elbow and she sprang lightly into the seat beside Elisha.

“This here’s Adam’s brother, ain’t? This here’s Elijah Maice, Herbie.”

The Herbie young man flicked an eyelash toward Elisha.

“Elijah, huh? Well, don’t let his ravens get you anyway! And don’t go forgetting your little city cousin while you’re out there among the hog raisers!”

“Oh, ain’t you awful?” giggled the Hepple girl. “Gid dup!” shouted Elisha. “Ain’t he awful yet?” The Hepple girl was the twitchy kind. She twitched at her glove, at a magazine, at the laprobe. “We ain’t relationed together. He just plagues me. He’s Uncle Jacob’s nephew, and I’m Aunt Mat’s niece.”

Elisha spat.

“Course he’s high educated that way. He’s got a decree, or whatever, at the law. He’s the leading and only lawyer at Heitwille a’ready.”

From the corner of his eye Elisha appraised that she was thin enough to be bounced out by a sizable rut. Suppose he maneuvered the wheels at just the right angle — she wouldn’t land hard, there wasn’t enough to her. Even if he did finally go back for her — if he did — the breath might be jolted out of her so that she’d be quiet anyway. He could see her sitting there by the side of the road.

What he really did see at that moment was another appraising eye. Upon him! A gray eye with an astonishingly black pupil. A pupil astonishingly penetrating!

He raised the reins high and slapped them down mercilessly. Old Bess flipped backward an outrages ear and lunged into a resentful canter. The Hepple girl bounced forward, then back—and settled closer to Elisha.

“Ain’t it kind o’ crispy though, now the sun’s gettin’ ready to set on us?”

Elisha heaved violently to his own corner. He felt the black pupils again turning toward him.

“It wonders me still,” pursued the Hepple girl, and her voice was soft now in meditation; “I thought Adam was sayin’ where he had a little brother. And here you’re a man a’ready. That does now make a supprise fur me.”

“Huh?” Elisha snorted, and was immediately sorry. He had made an iron resolution to suffer in silence his three miles of humiliation.

“Yes, I would guess anyhow! But mebbe he was playin’ off a joke on me. Or else, was you, mebbe, his big brother?”

“He ain’t got but one,” grunted Elisha. He surreptitiously glanced down the length of his arm, flexed its muscles. His secret shame had always been that he was not huge, like Adam!

“Now me, I’m so runty that way,” sighed his companion.

“You are that,” muttered Elisha.

“Course a body can’t help fur their size. But I guess that’s why I always take to big men mebbe.” Elisha shuddered. “Well, and women too. Aunt Mat always says, ‘My, I wisht if I wasn’t more’n two hunert, so I could be stylish like you,’ she says. But I say back always, ‘Well, what does it fetch to be stylish? Look oncet at Cousin Herbie. He might be stylish, but he’s awful skinny. Them kind don’t make nothing with me. I like fur to see ‘em heartier and more, now, comfortable lookin’,’ I says. ‘Comfort yet is what makes with me,’ I says.”

Elisha looked down distrustfully at an extremely pointed shoe slanted upward from beneath the robe. His companion immediately gave a wrenlike nod.

“I know. It looks some squinchy. But it ain’t. I’m just natured to that shape a’ready.”

Elisha again went sharply in search of his breath. What was this he had in the buggy with him anyway? He had never seen such swift reaction, such uncanny divination. He had always thought you had to tell a girl anything twice over before she got it. And here, almost before he had a thought, she was expressing it for him! And that foot now — was it possible that a woman’s foot really did grow into a point? Could it be that a girl did quicken into some strange new thing somewhere along? That she wasn’t just a meager edition of a man, weaker in both mind and body?

He squared heavily about and looked full at the Hepple girl. She twitched lightly about and looked full at him. Her eyelashes rayed out, very black and very long; their tips seemed caught together by twos and threes — caught together — caught — He gasped; his foot jerked heavily upward as though from some entanglement. The jerk pried loose his eyes.

He wouldn’t look at her again. What was the matter with him? A rein dropped from his demoralized fingers. He swooped after it. And as he came up, something slowly pushed his head around so that he looked at her again. Her eyes were still upon him. Her very soft, very red lips parted slowly, slowly curved.

He definitely clutched at anger. He grabbed the peach shoot and sliced blindly. It broke over the dashboard, dangled. He hurled it away and hissed wrathfully after it.

“What you intrusted in?” Should he answer her? “Poland Chinas,” he grudged. “Me too! I do now take to them Oriental things till it is somepun supprising. My, ain’t you up-to-the-minute though?”

“Pigs!” shouted Elisha. “Hogs! Boars!” She was a dopple after all! Didn’t even know Poland Chinas!

She considered. Then she gazed at him, gently forgiving.

“To be sure, pigs. Polish Chinas. But they come from China first off. And if they come from China, they’re what you call it Oriental, ain’t not?”

Each hair upon Elisha’s head rose in fiery curiosity. “China, still? From acrost the oceans over?”

The Hepple girl nodded decisively. “In such ships oncet.”

Elisha pondered this revelation of porcine genealogy. The girl gave a little sigh.

“But, anyways, what does it make? This here is what makes with me: Fur to find somebody where has the same intrusts like what I have a’ready. I do, now, take to such little pigs. I can’t otherwise help fur it. And I would bet, now, you’ve decided to go into pigs!”

Breath-taking! Elisha leaned back somewhat weakly.

“Well, anyway,” he admitted, “I took the prize for Juniors at the Grange two months back a’ready. Twohunert-and-sixty-pound shoat. Ten dollars.”

“Ten dollars still!” gasped his companion. “Since I am born a’ready, I ain’t hearing of nothing so intrusting!” She snuggled closer.

Elisha tipped his cap rakishly. He tossed off, “That ain’t nothing. I’ll git mebbe twenty, twenty-five, more on her yet. Till it comes next week, pop will be loadin’ stock fur the market onto a box car, and I’ll be a-fetchin’ off my share alongside the other — the other men.”

Then said the Hepple girl an amazing thing. “Before ever you was turnin’ in at Schindler’s, I seen it at you. Yes I seen it at you where you was one of the money men of Buthouse County a’ready.”

And she wasn’t joking! He swung upon her quickly to catch her. She was gazing up at him as innocently as a babe, and as helplessly, as helplessly. Her lips were parted as in breathless adoration, her eyes upturned deep pools, into which one might slip — or plunge —

“Whoa!” yelled Elisha, and subdued his steed from a gentle trot to a walk. “Whoa, anyway! What do youse want to make such hurry fur?”

His left side was growing very warm; oh, very! The girl looked bony, but she wasn’t. She flanked him closely, softly, like such a hot- water bottle; or, no, hotter, hotter, like one them mustard plasters now. His heart thump-thumped, thump-thumped. She lay against his heart! He had a sudden conviction, all pain, all pleasure, that he could not move if he tried! He was terrified, he was paralyzed; he had never been so desperately happy in his life.

As though soft veils had been laid over his ears, he heard her voice coming up, coming up, as though from far below: “Yes, well. I guess I would up and give it away if I would ever get such a ten dollars. Yes, I guess I would go to work and make some such inwestment at friendship, like I read off somewheres. And that would be awful silly, ain’t?”

“Yes,” agreed Elisha hoarsely.

Elisha, in fact, was in mood to agree with everybody. A half hour later when Mrs. Hoopstetter swam into the periphery of his bedazzled vision, he agreed with her. Mrs. Hoopstetter, with hairpin antenna emerging from the black coil upon the top of her head, her rounding form incased in black calico with red polka dots, bore an unmistakable resemblance to a potato bug as she ambled toward them from her kitchen door.

“Well, was this, now, Cory Hepple? Ain’t you growed though, since you was a baby a’ready? And if this here ain’t Elisha a-fetchin’ you! Come insides and set along fur supper, Elisha. The Wieners is all made and the coffee’s on the boil.”

Still later he agreed with Cora Hepple when she indicated that he was to sit down beside her upon the settee and to devour with her the magazine which she had carried from the Schindlers’.The name of the publication as it was emblazoned above a polychrome pirate rampant upon its cover was Up to the Minute; and its date was the month previous.

That Miss Hepple was a devotee of literature might have been inferred from the general indication of wear and tear upon the publication; but she disclaimed any tendencies in this direction when Elisha cast a gloomy eye upon it and gloomily shook his head in answer to her question.

“Nor me neither,” she confessed promptly. “I ain’t addicted to readin’ off just one word and then another. That there’s a waste of time, ain’t? But I do sometimes go to work and read what it makes at the adwertisements. Now, fur instinc’, it wouldn’t wonder me none if we was to run into some such pigs over behind.”

Fascinating as were pigs, however, they were not so fascinating to Elisha at that moment as the fingers which were flying in search of them. The lamplight coruscated over the nails which tipped them like they were—well, like they were freshly shellacked, now. He drew his brows as he gazed from them to his own, dull and spatulate, and finally queried bluntly: “What is it at them? Warnish or whatever?”

She looked up at him inquiringly, then laughed softly, tipping up one shoulder, then the other.

“Oh, I’m just natured that way at the nails. It’s fierce, ain’t not?”

“Yes,” breathed Elisha. Pointed feet — shining nails. He slid from her. And why not? It is an awesome experience to discover a new creation.

She uttered a sharp exclamation, laid the magazine flat upon her knees and placed five of her amazing finger nails upon her heart.

“Och, my! That there makes me dizzy at the head! Why, it’s just what I been always dreaming about!”

Elisha looked down at the page. He saw nothing remarkable. “It ain’t nothing but a ring,” he said.

“A ring!” gasped Miss Cora. “A ring with rubies at!” She thrust the publication into his hands. “Read it oncet!”

Above, below and surrounding a particularly angry-looking ring from the stone of which fiery rays darted to the bounds of the column were the words:

STARTLING GEM OFFER

Our exclusive MILLENNIUM RING, known to satisfied thousands. Blue-white stone, perfect cut, set in elegant white-gold cup, surrounded by

CHOICE OF EMERALDS OR RUBIES CREDIT TO OUR FRIENDS This means you!

EXTRA SPECIAL

at $29.50Simply enclose $10.00. Balance $2.50 per week. Our investment in friendship. We take all chances

LIMITED SUPPLY ORDER NOW

Elisha shook his head darkly and handed back the magazine.

“Say, now,” he warned, gazing down at the innocent little creature curled up beside him, “don’t go fallin’ ower this here! It might be some such trick in it. Them city sharpers — ”

But look who it is a’ready! The Old Honest Goldsmith, H. Chadwick, Inc. I’ve knew about Mr. Inc since I was born a’ready. But what does it make to talk?” She spread her ten tiny empty fingers in a gesture of resignation over the piercing rays of the ring. “It ain’t nobody where would go makin’ such expensive inwestments at friendship just ower me! Eut och, my! If anybody up and got me such a ring with rubies at I wouldn’t have eyes for nobody else, it would go that silly with me. I have afraid anyway — ”

But she was not so smitten with fear at that moment as was Elisha. He sprang up, kneecap cracking. His body slanted tensely toward the closed kitchen door, through which a voice was thundering:

“What does he mean by somepun like this anyhow? Lettin’ the cow to milk fur me! It should give a good thrashing fur that one!”

“Your pop!” gasped the girl with lightning intuition.

Elisha did not pause to identify his parent verbally. He was already wresting open a door on the opposite side of the room. He whizzed through the chill dank of a parlor, wrangled a huge brass key at the ceremonial front door and zoomed out into the blackness of a porch.

“I got to go. It’s gittin’ late on me,” he clattered back over his shoulder.

But he had not counted upon the celerity of his hostess. She was there beside him. Even as he landed upon the top step she thrust something beneath his arm.

“Take it along with! We ain’t looked fur them China pigs!”

Elisha had no need to urge upon old Bess that time was the essence of their contract; she had not yet had her supper. She legged off the mile and a quarter between the two farms with such impatience that Elisha had fed her and had bedded both her and himself before he heard a door slammed in paternal wrath beneath him. He lay quivering in the bed beside the sleep-drenched Adam until he heard his father’s footsteps clanking off to their own room; then he nested down with a great sigh.

It was long before the boy Elisha really slept. And yet, was it the boy Elisha who lay taut between the blankets that night, his forward jut of chin thrusting upward into the crisp air, his deep eyes matching the depth of shadow in the room? Had not the boy Elisha gone to sleep, beyond recall, two, three hours before? It was a naked soul, an elemental, at grips for the first time with the most powerful of the powers of the air. For assuredly it was not a man, this skinny thing which had finally much ado to keep from blubbering, from clutching at the big warm Adam and blubbering that he hadn’t meant to do it, he hadn’t meant to take Adam’s sweetheart from him; but she just would have him, she just would!

Between his tossings, as he lay still-eyed, came again and again a memory seemingly detached from all he was thinking and all he was feeling: A long, long time ago when he was six and Adam was nine, the two of them, stumbling down the hill, behind their father, from the new grave under the beeches — Adam clutching his fingers until they hurt and whispering thinly: “You got me anyway! You got me anyway!”

And this was the Adam the was hurting! This was the Adam he was robbing!

He awoke, as usual, to the vigorous rattling of the stove in the room below. Adam did everything, not quickly, but vigorously. No brighter pans than Adam’s in any kitchen of Buthouse County; no straighter furrow in any field. No better corn cakes turned for any table; no cleaner garden patch behind any house. It always had been rather fun to keep house with Adam; it had seemed no woman’s task as Adam had carried it on, with slashing broom and swishing brush.

But today it was no fun. Elisha slunk about, with eyes down. Oh, he was heartbreakingly sorry for Adam!

And yet his heart beat with terrific triumph. Triumph that took him spasmodically by the legs and flipped him into a handspring. Triumph that took him by the wrist and made him shy a hatful of duck eggs, one by one, against the corncrib.

But there was no compromise in him. The jut of his chin was thrust definitely toward manhood — manhood symbolized, curiously enough, by that girl a mile and a quarter distant. A mile and a quarter? A world distant! And time — this was Friday — tomorrow Saturday. Well, Saturday night, then.

Upon his shoulder fell a heavy hand.

“Now, what about Saturday night?” demanded Adam. “Was you tellin’ her a’ready I am keepin’ comp’ny with her Saturday night?”

Like a bronze frog Elisha squatted, motionless. The hand twisted impatiently. Elisha slowly reached for a weed, slowly plucked it.

“It’s somebody else — settin’ up, keepin’ comp’ny — Saturday night,” he brought out. The hand jerked him, dangling slantwise, to his feet.”Somebody else?” roared Adam. “Who else, then? Answer me up now! That sleazy Schindler?”

“She — ain’t sayin’.”

“She better not be sayin’!” gritted the terrific Adam. When he knotted his fist like that the wrist tendons whipped out like live cords. “He’ll git the right to git his neck twisted off fur him.” He stalked away, kicking the clods.

Elisha oozed down upon the ground. He gazed after Adam, then he knotted his own fist and stared down upon his wrist; there were no cords there! Well, maybe, just maybe, he wouldn’t interfere with Adam, Saturday night. But at that moment between his young ribs began to creep and whimper an alien thing, a spawn of distemper which was finally to strangle—and strangle—his love for Adam.

Hot of eye, hot of heart, he watched Adam on Saturday night as he bathed in the zinc tub behind the kitchen stove, as he covered his long clean muscles with splendid raiment, as he carefully parted the bronze glow of his hair and carefully curled up the lopside of it over his finger, as he donned his hat with slow deference to this same curl that it might follow the upward tilt of the felt. Adam never knew that when he closed the door upon his festive person, a man with the ache to kill shot to his feet with clenching fist and kicked murderously the leg of the table with the brass toeguard of his shoe.

But — he couldn’t endure it! He cast a quick glance upon his father mumbling over the livestock quotations, raped his hat and coat from their nail and let himself out of the door. Down the lane crisped Adam’s wheels upon the frozen ground; down the lane sped Elisha. He caught the tail of the buggy at last, jerked along agonizedly with it for a moment, then with a mighty heave landed in a clutching heap upon its narrow tail.

Ignominious, of course, jolting along back to back with Adam, the tailboard bruising into his flesh with every rut. But he was going, at any rate; he was getting there!

He got there, and he crouched like a the Hoopsetter wagonshed while Adam blanketed old Bess. Like a mouse scurried to the window of the living room.

There, there she was—upon the settee just as he had held her in memory! The light from the hanging lamp made a nimbus of her dark curling hair. Her little feet, those pointed feet, were tipping gently this way and that. And her eyes, those wide innocent eyes, were also turning, first this way, then that. Upon whom? Upon the male Schindler and upon Adam, upon a disgruntled Schindler and upon a glum Adam with arms upright like stanchions upon his knees. There they sat, the three of them; and outside, loving, hating, Elisha. Outside, feasting, starving, Elisha.

Outside, that was it. Shivering’ for a quarter of an hour, there, outside. With a hard gulp he swung from that window at last. He had determined what he would do. He would do that which he had told himself for two days that he could not do.

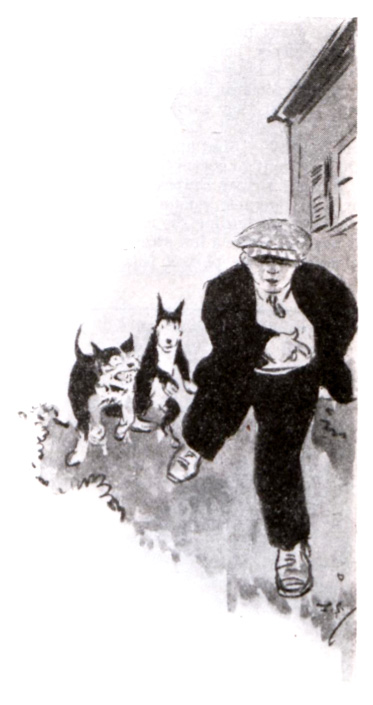

He could not do it fast enough now. He lunged into a run, the aroused Hoopstetter hounds in full yelp behind him. The whole universe seemed in clamor. He liked it. It seemed right, considering the momentous thing he was about to undertake.

The house was dark, as he had expected, but he paused for an alert moment inside the door, his ear cocked cannily upward toward his father’s bedroom. Then he tiptoed into the parlor and abstracted from the paternal stock of stationery between the leaves of the family Bible an envelope, a sheet of paper and a stamp. There was no need to withdraw from the lair beneath his own mattress the phrenetic pirate guarding the Startling Gem Offer of H. Chadwick, Inc. Did he not know by heart every syllable of the Old Honest Goldsmith?

Under slowly weaving tongue Elisha composed his first business letter, which for brevity has probably never been excelled in all the annals of financial correspondence:

Heitville Rural F D

Dear sir Mr Inc I send you still ten dollars. You send me Milennium Ring A3035 as per

stricly confidential. With rubies at.

yours truely

ELISHA MAICE

The letter was only the husk of renunciation, of course. He swallowed the bitter kernel when he gazed his last upon the ten-dollar bill which had lain so warmingly above his heart. It dimmed into twice, thrice its size as he bungled it into the narrow white casket of his hopes beside the letter to Mr. Inc.

Well, anyway, the little canvas bag was not empty; it still contained two dollars and seventy-five cents — no, eighty-five, with Adam’s dime. Two fifty for the first weekly payment, and something over. And within the week his father would be back from the stock market. It was all so safe, this investment in friendship in which Mr. Inc took all chances.

What really troubled him as he set out at once on a trot to the mail box at the crossroads — for had not Mr. Inc warned that he had but a Limited Supply? — what really troubled him on that half-mile trip was that he had not been able to accept the Old Honest Goldsmith’s Sacrifice to the Public as set forth upon another full page of the magazine: The Mammoth Complex Dinner Ring; a Constellation of Seven Large Diamonds: Only $49.50, $15.00 down, $5.00 weekly. But, anyway, she had said she liked rubies. He saw again her ten tiny empty fingers spread above the pictorial rays of his ring — her ring — their ring. How surprised she would be when she opened the Royal Purple Plush Gift Case!

He could keep his secret, Elisha could! But he kept it at fearful odds when he sat once more upon the settee and proffered the portentous magazine to its owner.

“And was you findin’ pigs at? Or, mebbe, somepun else intrusting?” she queried softly.

Elisha dug his heel into the carpet and shook his head. But she looked so concerned, so unutterably downcast that he found himself encouraging:

“Not anyways pigs. But I’m a-findin’ somepun else. I’m a-findin’ somepun else yet in that there book.”

She looked up at him quickly. Then she trilled into gratified laughter. “What, anyway?” she whispered. “Tell me oncet!” He could feel the little confiding heap of her against his elbow. He heaved chastely from her.

Entered Mr. Hoopstetter with rattling newspaper and clanking boot.

“Is Maice a-loadin’ his hogs Monday, then?” he queried grossly as he turned up the wick of the lamp. It reads here where the market goes draggy at the soft pigs. I ain’t a-lettin’ mine till the price stiffens at them, that I give you.”

Ominous words over which Elisha might well have felt apprehension, considering that his own financial solvency depended upon the prompt conveyance of his shoat to market! But all he was feeling for the moment was an intense dislike of the Hoopstetters; for Mr. Hoopstetter, who scraped his chair noisily underneath the hanging lamp; for Mrs. Hoopstetter, who ambled in with gingham apron overflowing with woolen socks, a darning needle stilettoed into her bosom.

They were always there, the Hoopstetters. It seemed as though Miss Cora Hepple was the only person in the world who recognized that he was a man.

“You ain’t gittin’ stuck after Cory, ain’t you?” Thus Mr. Hoopstetter with ponderous playfulness during that first week of Elisha’s daily visits.

Oh, yes, sometime during the day or during the evening Elisha managed to cover that mile and a quarter between the two farms. Sometimes he had only the two Hoopstetters to contend with; sometimes he had Adam, sometimes the damp-haired Schindler; sometimes he, Adam and Schindler sat in a jagged semicircle of hate beneath the hanging lamp. But Elisha gritted his teeth and held his place; he was openly in the running; he was shamelessly sure of his position with the lady. He knew that she simply endured the others because she was too gentle to rid herself of them.

If he was sure of the eternal bond between them during the first five days of their acquaintance, he was doubly sure after that. For on the fifth day appeared beneath the rusty tin flag on the Maice mail box, the ring. Be it said in honor of Elisha’s rare restraint that he had it in his possession, in a hot lump, in a cold lump, in the canvas bag upon his chest for a full hour and a quarter before he delivered it. It came in the morning; he would wait until night. But night was an eternity distant; anything might happen; they might both be stricken dead! And with night might come Schindler or Adam or both. He dropped his ax at the woodpile, sauntered slowly under Adam’s eye to the barn and through it, then tore across fields.

Of course, though, somebody had to interfere! Elisha dodging from one door to another of the Hoopstetter domicile, buffed full into Mrs. Hoopstetter as she ambled around the corner of the house.

“Bei meiner seele!” she gasped, rocking tumultuously. “It’s Elisha oncet! But you look some pale, bubbie. Ain’t you anything so well? Did you got a pain at your stummick or wherever?”

Was ever swain in travail to present a love token interrogated as to the condition of his internal organs? Elisha groaned.

Appeared in the window behind him a pink sunbonnet. He cast upon it a glance of despair.

“I see a’ready where I have overstepped myself,” chuckled Mrs. Hoopstetter with obscene mirth. “He has got it at the heart still. Not anyways at the stummick.”

By lover’s guile Elisha abstracted his lady to a position behind the barn, and ensconced her upon a wagon tongue. His fingers, numb with ecstasy, fumbled forth the plush case. The sliding door crashed open behind them. Mr. Hoopstetter strode triumphantly forth, girt with a pitchfork, and bearing a large conical trap in which a small rodent squeaked frenzy.

Elisha rose in stiff-legged rage and retired his companion, squealing delicately, from the arena of slaughter. The animal in his trap could not have felt more baited than did Elisha as he cast a hunted eye about him. The landscape proffered no inviolable shelter; the fields, the flat garden patch behind the house, the family orchard with its leafless trees Toward the orchard strode Elisha with the pink sunbonnet in wake.

Arrived to the rear of these puny trunks, Elisha again brought forth the Royal Purple Plush Gift Case. For five days he had been framing verbal sentiments appropriate for the occasion, but the untoward circumstances of th’ hour and his own overwhelming emotions of the moment choked the words at the thither end of his Adam’s apple. He silently extended the box and leaned back pallidly against an apple tree.

The moment was more satisfying, much more, than he had even anticipated. She gave a little cry, then a gasp, then another little cry. She plucked the ring quickly from the box and slipped it upon her finger. “A ring — with rubies at!” she breathed; and kissed it!

She flung toward him and reached up her arms. Elisha backed blindly. He took one of her hands and shook it earnestly. She looked up at him, puzzled, a red curl swirling up into her cheeks. She laughed, as though uncertain what to do next; and stood, turning the ring this way and that.

“Ain’t it is wonderful? And such a supprise on me! Och, my! Since I am born a’ready, I ain’t seeing such a grandness!”

Elisha said nothing. He merely looked, his hand at his throat. It was his moment. Nothing would ever take it from him. He would see it always as he saw it then: The trees with their limbs naked in their sleep, and beneath them the girl, vivid, quivering, a slender lance of life, twisting this way and that upon her pointed toes, her bright glance flashing from him to the red stones upon her finger.

“My, ain’t you the swell feller though! And the good guesser yet! I was wishing long a’ready fur a ring with rubies at. It will git me proud to my head, I have afraid, anyway!”

When at last Elisha found himself treading the impalpable air toward the rear of the house, he halted her abruptly at the garden gate.

“Look here,” he panted, his greenflecked eyes upon her, “you leave me be your steady friend. Youse won’t be leavin’ them other two set up by you no more, ain’t not?”

The girl went slowly through the gate and faced him across the pickets. “Well, this here is how it goes with me. I am softhearted that much that I can’t, just to say, go sassing them off. Herbie he’s my cousin — from — marriages that way; and Adam he’s your brother, ain’t not?”

“No!” shouted Elisha, and added with dizzy penitence: “Anyways if he is, he ain’t no more.” He plucked at her sleeve as she turned from him. “But pass me your promise, anyways, where you ain’t travelin’ with him to the Ewangelical picnic. Nor with Schindler neither. Pass me your word you’re goin’ with me and not nobody else. Till it comes Saturday a week?”

“Saturday a week?” she mused, chewing the string of her sunbonnet. Then she laughed suddenly. “That I will oncet. I’ll go with you and I’ll stay with and I’ll come home with. I pass you my promise on that!” She glanced over her shoulder, twisted off the ring and clapped it into her pocket. “There’s Uncle Willie!” she whispered. “And this here’s our secert! Just us both two together! Ain’t not?”

For, of course, a Hoopstetter had to churn across that ineffable moment. Mr. Hoopstetter, angrily sideswiping at the ends of his mustache with his side teeth, crossed the back yard toward the tool house. He was carrying the large glass bowl of the hanging lamp.

“Such a wear on the coal oil!” he groaned loudly. “Sooner I git it filled, sooner it goes empty on me agin! I will give them mealymouths dare fur to pack their own oil along, that I will oncet!”

“Sh-h-h!” pierced Mrs. Hoopstetter from the kitchen door.

Scratching exultant ribs, Elisha hurdled homeward. She was going with him to the great social event of the year, the Evangelical Sunday-school picnic! Arm in arm they would parade all day, to the bitter envy of Adam, Schindler and other desolated suitors! And after that, there would be no question as to whom she belonged to; she would be sealed to him and to him only! As he vaulted the last fence he saw Adam swinging his discarded ax. After all, good old Adam! Poor old Adam!

Adam spoiled it all. Leaning upon the ax handle he smiled under frowning brows. “I’m a-goin’ to work and thrash you one if you don’t stop pesterin’ my girl. Now mind it! And here’s somepun else: You got to stop follerin’ me nights or I’ll give you a shamed face in front of her, for I’ll go to work and lay youse ower my knee yet. What do you conceit you are, anyhow, carrot-top? A man a’ready?” Elisha’s eyes darkened from blue to black. His shoulders drew stiffly upward; he lowered his fiery young head like a young bullock and dived straight for his brother’s middle. A second later he was being held at arm’s length like a helpless manikin. He saw haze. He hissed and drooled.

“Why!” gasped Adam. “Why!” He dropped Elisha. “Poor little brat!” He stared at him in amazed comprehension.

Poor! Little! Brat! Each one an insult. All three, a triple insult.

“I hate you!” stifled Elisha. “I — hate you!”

He did. From that moment he hated Adam as fiercely as he had loved him. And he hated most the things he had loved most — Adam’s strength, his good looks, his kindness.

The hate swelled within him as the slow hours of that day passed until it seemed that it was all of him, that there was room for nothing else. But there was. There was room for active apprehension. It was his father who introduced the new agony.

Maice Senior was a stern, silent man. Silent Silas, the county called him. His tongue muscles might have grown flabby had he not exercised them nightly over the newspaper. He invariably read aloud, mumbling the news, droning the quotations. He read even the quotations which did not financially concern him, such as Drugs and Dyes, Metals, Hides and Leather, Turpentine and Oils. He usually fell asleep midway of Turpentine and Oils, awoke strangling, blew his nose and went off to bed.

This night Elisha, somberly hunched over the stove with his back toward the others, would have been oblivious of anything unusual, had not Adam suddenly clanked down the tools with which he was half-soling Elisha’s shoes and inquired in a strange voice: “What was that now? Was the hogs fell agin?”

Mr. Maice droned again: “‘Slow, mostly 25 to 50 cents lower. Packer top $6.10. Shipper top $6.00. Packing sows, fairly active, $5.25. Few fat pigs, steady, around $5.25.’”

Adam did not take up his tools. After a moment he ventured: “Then you wouldn’t, mebbe, be a-loadin’ them — this week?”

Mr. Maice snorted grimly and shook his thick grizzled thatch. He adjusted his paper and started upon Hides and Leather.

Still Adam’s tools remained silent. Elisha turned startled, bloodshot eyes toward his father and shrilly challenged forth his one remark of the evening: “My shoat’s Packer Top, $6.10!”

“Wet Salted Markets Finn,’” intoned his father. “‘Skins Stronger. Tallow Markets Easier. Take off of. Butcher Pelts steady —’”

Elisha slept little that night, not at all in the early hours. How could he, with insolvency pressing upon him, blacker than the night about him? Soon, horribly soon, his first weekly payment would be due. He clutched at the canvas bag beneath his nightshirt and tried to imagine that it still contained two dollars and eighty-five cents. But it did not. It contained one dollar and sixty cents. Yet he could not regret the red tie and the red-striped socks which had so devastated his hoard. Had she not said she liked red? He could even, in that sorry pass, have laughed aloud at Adam. Adam had recently purchased a green tie and a hat with a green band. Oh, yes, he was hating Adam as he lay there! He lay on the edge of the bed; he would not have touched Adam’s body for the world; he had even considered sleeping in the barn. He started at a voice in the darkness: “Say, give me the lend of that there ten dollars, wouldn’t you? Just till pop goes comin’ back from the hogs?” Elisha lay taut. “No,” he finally brought forth. Adam tossed restlessly. “Aw, now, say!

Leave me git the lend of them ten dollars and I’ll put a dollar or whatever to it.” Silence. I’ll swaller back what I said about my girl, all, if that’s what’s eatin’ you. I give you dare fur to tag me to Hoopstetter’s ower.”

His girl! Tag him! Elisha projected his outraged self perilously over the edge of the bed. “Take another guess if you think it!” he sliced. “I guess youse couldn’t git nothing off a poor little brat’!”

He lay in tremble. For a few moments he heard nothing, felt nothing, tasted nothing, but his own bitter words. He was tense for Adam to speak again. Adam did not. That hurt.

He was surprised that Adam, also, was in financial straits. But it was easily accounted for. Adaam had purchased the top buggy a week after the girl had twinkled into Buthouse County upon her amazing little feet. Adam had gotten the buggy for the girl; and now he had gotten the girl from Adam. After all, poor old Adam! He began to hate hating. Loving, now, you just couldn’t help; it just came. But hating tore you. And yet you couldn’t stop.

There he was; and the fun was all gone during the days that followed. And yet he had never been so fiercely happy in his life. Fiercely, that was it, when he was with the girl.” I do now take to you that much! she would say; and Elisha would shiver hotly down his back. But away from her, that was different; away from her, fumbling at the limp bag and speculating as to how long the unknown Mr. Inc would be willing to take all chances; away from her, harking with smitten ears to the evening reports of a dropping hog market; away from her with a strange alienated Adam stumping glumly about house and field. Gone the martial slash of broom and shovel and brush and ax; gone the banter with which Adam the resourceful had imparted a tang to life. “It’s time fur to milk the milk!” he was used to yodel as he swung the pail from its high hook and tossed it to Elisha. Now Elisha reached for it in silence, in silence filled it and in silence slopped with it to the spring house.

Once he slanted his tormented forehead against the rough red pelt of the cow, bruised it there, as he thought that he would give anything, even the girl, if he could only tack back to the old happy days with Adam. But that was a black thought, treacherous to the girl; he knew it that night when she took the ring from her pocket, slipped it on and murmured: “My, I do now set awful store by this tony ring! And mebbe I ain’t settin’ store by youse, too, Elisha!” The rapture of the moment was chilled for Elisha by a curious defection of his eyesight. Glancing down upon the jewels he saw them as green instead of red.

“Why, what is it at them?” he stammered.

Miss Hepple giggled, thrust her fingers into her pocket, twisted from him, and a moment later the rubies flashed before him. “Was you blind or whatever?” she twitted him.

Mr. Inc did not keep him long in suspense — or did he only deepen his suspense? The Old Honest Goldsmith began to use stationery recklessly. Elisha, cannily meeting the mail carrier a full quarter mile from the house, had delivered into his prescient fingers once, twice, thrice, typewritten statements and letters from which emanated a chill formality lacking in the initial correspondence between them.

Stumbling homeward with the latest of these documents, Elisha read and reread the ominous statement: “If the obligation is not paid forthwith, we will take such other and further steps as may be necessary to protect our interests in the matter.” How long was “forthwith”? What would be the “steps”? Elisha sagged down under some sumacs to consider these momentous questions.

He was presently distracted for a moment. At a point where the mail man’s circling detour rejoined the main road Elisha saw Adam striding forth to meet the gig.

He was handed something; he went slowly up the road, head down. Was Adam, too, hailing the mail man surreptitiously?

Elisha returned home by way of the Hoopstetters’. His sojourn under the sumacs had yielded a single forlorn possibility. If it failed, ruin was upon him. But if he could get possession of the ring and return it in hasty loan to the importunate Mr. Inc, would not the jeweler be appeased until such time as he could redeem it? If he could.

But he couldn’t. He saw that at once when Miss Cora Hepple clapped her hand over her pocket and backed from him. “I’m that fond fur it, I would up and die if I was to lend it away!” she informed him.

“Just till it comes next week!” Elisha pleaded desperately. He shifted heavily from one foot to the other, then made terrific compromise with Fate: “Give me it oncet, and I’ll change it off fur the Mammoth Complex Dinner Ring. Seven large diamonds. Forty-nine fifty still.”

This gave Miss Hepple pause. Her red little mouth quirked, considering. “I tell you,” she confided, “I give you dare fur to borrow it at the picnic. Or was you, mebbe, fergittin’ to remember I was keepin’ cornp’ny with just only youse that day?

Was he forgetting? But — the picnic was still six days distant!

Under the barn rafters that afternoon, upon the haymow, he composed another frantic letter to his creditor. Adam’s voice came from below.

“Say, pop, market’s up a quarter cent. And the agent at the freight says we could git a empty box car off the siding. I could go drivin”em in this after; and youse could start behind daylight tomorrow. He says. Where he’ll go hookin’ the car at the freighter where pulls through at four of the A.M. The market might go to work and fall on us agin if we go waitin’.”

Elisha stiffened with his held breath. But he could hear only a discouraging mumble. Ordinarily in the Maice family that would have ended it. “But,” Adam’s voice whanged nervously, “we’re just throwin’ good corn into them! We’re a-losin’ at them day after day. We could git — ruined over them!” This last held the crack of hysteria. There was silence.

Even hating Adam as he did, Elisha could not forbear a grudging admiration. No one had ever stood up to his father like that. But — ruin! And Adam didn’t know, and his father didn’t know, how closely the ugly word was hovering over the peak of the haymow at that moment. It all depended upon the time in which Mr. Inc would take those portentous steps as to whether Elisha would be crushed beneath them or not.

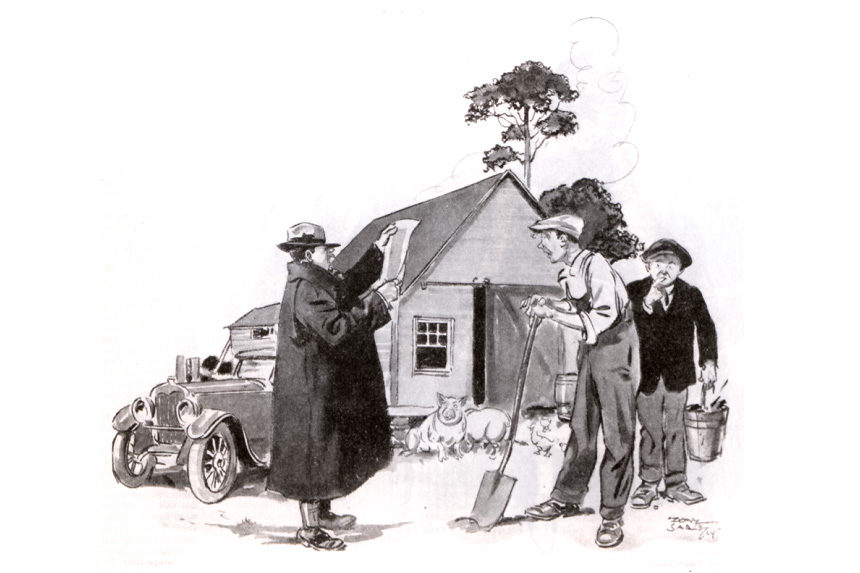

And yet he did not recognize the steps when he finally heard them approaching. They approached, in fact, upon wheels. Three afternoons later when he was cleaning the stalls, he heard an increasing roar, then a series of dying bangs. He ran to the door.

The male Schindler throned in the barnyard in his small automobile. Adam stood rigid, shovel in hand.

The visitor was exaggeratedly slow as he unbuttoned his overcoat, unbuttoned his coat, felt in one inside pocket and then the other, and finally pulled forth a long envelope. No judge upon tribunal ever looked down upon the docks with more implacability than did Mr. Schindler as his gaze swept from Adam to Elisha.

“I have here a certain legal dokiment which authorizes me to replevy two certain properties described as follows and to wit in this here letter which I hold at the present minute in this here hand.”

He paused and again surveyed his quarry with judicial omnipotence.

Adam shook his shovel. “Git it through, then! But speak it in English!”

The visitor stiffened and scowled. “The H. Chadwick Company, Inc., has up and constituted me their attorney-at-law and as such I hereby make demands upon you and each of you for delivery of the possession of said two rings for which you have failured to comply with the contracts you have entered into with said company a’ready. And as aforesaid I now make demands for the conveyance to me of those two certain properties known and described in said letter as rings.”

“Rings!” roared Adam. “I ain’t never bought no two rings! If your bum comp’ny goes a-tryin’ to git any two rings off me, they’ll git their heads busted off fur ‘em. I went and bought a ring, yes, that much I give you. But I ain’t got it by me and I can’t git it, and that’s all to it.”

“There’s two defendants in this here action,” intoned Schindler imperturbably, “and they’re specified in this here interment as Elisha James Maice and Adam Charles Maice. And if you failure to yield up said rings into my possessions herewith, I will require you and each of you to pay me a large attorney’s fee all of which is provided for in said contracts — ”

He stopped, mouth open, and gazed upon his disrupted audience. At mention of their respective names, Adam had whirled toward the pallid Elisha.

“Look here!” he said hoarsely. “You ain’t up and bought no ring! Answer me up now! You ain’t bought no ring!”

Elisha wriggled futilely under his stout hand. “I guess I had dare to buy it if I wanted to,” he said stubbornly.

Adam took his breath on a hissing intake. “You little dopple! Give it up, then!” He shook him. “Give it up! He’s got the right to lawyer it off you!”

Elisha’s throat was beginning to hurt. “I can’t,” he choked. His agonized glance flew involuntarily toward the Hoopstetters’.

“It ain’t — there?” demanded Adam. “She — she ain’t took — a ring — off you?”

Elisha gulped.

Adam’s hand fell. He, too, gazed for a silent moment toward the Hoopstetters’; and in that moment faith, hope and even charity died from his face.

He walked slowly toward the machine. “We got the two rings all right,” he remarked heavily. “But we ain’t got ‘em by us. They’re ower by — Hoopstetter’s.”

The papers crackling ostentatiously between the legal fingers lowered suddenly. The legal person himself metamorphosed before their eyes from the leading and only lawyer in Heitville to a Herbie young man with weak, very damp-looking hair.

“You don’t mean —Hoopstetters’? “he fumbled. His incredulous eyes wavered from Adam to Elisha. “Why, it ain’t true! I know it ain’t true! Why, she told me she ain’t got but one—and you never give her that!” He clutched at dignity, at authority. “Get in here!” he commanded. “We will see oncet!”

In the Hoopstetter lane Mrs. Hoopstetter was ambling about a small, freshly started bonfire, prodding it with the handle of a defunct broom. As the equipage with its freight of young masculinity ground to a stop beside her she chastely thrust further within the wreckage a pair of pink stays.

“Was you comin’ from seein’ her off, then?” she greeted them.

“Off?” squeaked Herbie. “Off?” bellowed Adam. Elisha merely formed the 0. Mrs. Hoopstetter reared back in amazement. “To be sure, off. Back on the trainroad to Stutz City. But ain’t she tellin’ youse? She had got only leave or what you call it fur two months. So, when her off was all, back she had got to go to the fact’ry agin. But, my souls” — her jovial gaze swept from one to the other of the stricken faces in the car —”don’t do it to go takin’ it so hard now! I ain’t a-crying none, nor neither is mister yet.” Mrs. Hoopstetter leaned like an oracle upon her staff and thus cryptically spake: “There’s comp’ny, that I give you; and then agin, there’s other comp’ny. Some such you cry somepun ower; and then agin, some such others you ain’t.” She turned and jabbed at a phrenetic pirate, who, though the flames were licking about him, still breathed polychrome defiance toward the faces above him.

“But — she can’t be gone!” gibbered the demoralized Herbie. “Why, she was going to the picnic with me!”

Adam leaped from his seat. “With you? I guess anyhow not!” He jerked, glowering, toward Mrs. Hoopstetter: “When did

she went, then?”

“Well,” calculated Mrs. Hoopstetter,

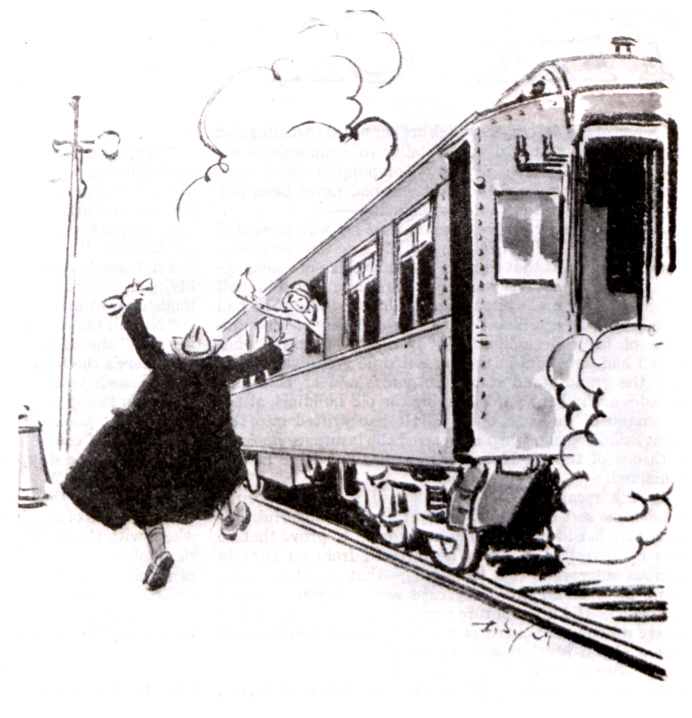

“I guess it was, mebbe, ten minutes back a’ready, or either eleven. The hired man packed her to the water tank where you make that way with the flag. Yes, mebbe you could ketch it, Herbie, if you make hurry plenty. But it does now wonder me terrible why she ain’t — ”

What she wondered was lost in the startled whir of the engine. But one remark was made during the journey. “She’s takin’ on water,” Schindler gritted as they whirled through a covered bridge and caught sight of the water tank, and at its base a huge dun caterpillar in three segments. Schindler was once more the stern exponent of the law; his fragile machine fairly careened under the weight of his Jovian frown.

Elisha numbly shunted his legs from the car and numbly followed the others around the end of the train. His middle went limp when he saw her. He knew she could explain; he had not lost faith in her for a momerit. She was leaning out of an open window; her head was turned from them; she was talking animatedly to the conductor.

“I should guess I ain’t from these here jaky parts! To see that, I guess it wouldn’t take no dummy. And, say, mebbe youre think I ain’t glad to git back where it makes more lively.” She saw them, then; at least she saw two of them; Elisha could not drive his wretched self forward. He saw her clap smitten fingers to her face. He saw Schindler grab his papers from his pocket and wave them before her. He saw her red lip curl back over her teeth—but it was not the smile he knew. And after moments he heard her—or did he hear her? — those strident tones!

“The law on me yet! I never heard the likeness! For just only takin’ such presents that way! Ain’t you the smarties, though? Well, I ain’t givin”em back, and that’s flat enough plenty!”

A red flag of defiance shot through her cheeks; but her eyes blinked with fright. They flew desperately toward the engine.

The conductor laughed. Others began to laugh. Heads appeared in windows, projected out from the platforms. Elisha could not bear it. He sprang forward.

“Don’t fault her none!” he choked. “I give it her fur keeps!”

Adam swept him back with a powerful arm.

If she saw him she gave no sign. Her trapped eyes swept him impersonally as they darted this way and that. Her knuckles clenched stubbornly against the window ledge. Then with one of her swift gestures she stripped.a ring set with rubies over a burnished nail, stripped a ring set with emeralds over another burnished nail, and dropped them like hot coals into Schindler’s upturned palm.

The antiquated engine gave a snort, ending in a long sigh. The train shuddered. The conductor with a cry of warning sprang upon the step.

“Here, you!” yelled Herbie Schindler. “That ain’t all! You give up that there other! My ring!”

He sprang toward the steps. The conductor sternly shouted him back. He ran along by the side of the moving train, screaming incoherence. From a window waved a hand with shining nails, and upon it a Mammoth Complex Dinner Ring. Schindler backed toward the tank, staring vacantly.

“Forty-nine fifty! In a lump! Forty-nine fifty yet!’

They all stared vacantly at the train as it puffed angrily from them. No one moved. No one spoke. They scarcely breathed. The tension grew, and grew terrific.

Emotions wound and tangled — tighter — tighter.

Schindler rasped in with a grinding swing of his heel and a scratchy laugh: “The little feist! I’ll fetch her yet and twist her that ring off! The skinny little devil!”

Elisha turned glassy eyes upon him. He slowly swelled; he slowly hunched. He lunged toward the legal ribs, striking out with both fists.

Schindler staggered; then with a backswipe of his long arm cut Elisha to the ground. With a roar Adam was upon him. They went down in tight crash.

They clenched and rolled there below the water tank. Elisha wound his arms tautly about his body and danced round and round them. He plucked at them, at Adam and at Schindler; he ached to be wedged between them, battering and being battered.

It was over in a minute, of course. Schindler was no match for Adam. Adam got up and stared down at the other.

Schindler waved his arms like feeble antenna and swayed to his feet. He felt of his nose, of his forehead. His fingers cruised his pockets. Adam whipped out a bandanna. “Here, the,” he said.

Schindler took it and mopped his forehead. He smiled, and looked down. Adam smiled, and looked down. Without another word they turned toward the machine.

But Elisha had had no relief. He made little whimpering sounds like a small animal in pain. He walked crookedly and he walked past the car.

Adam grabbed him and hoisted him into the tonneau. The fields seemed to tip up on either side and to make a dim funnel through which they rushed.

But it seemed to him afterward that Adam had reached out and had clutched his fingers until they hurt. It seemed to him he had heard him whisper thinly: “You got me anyway! You got me anyway!”

They got out. But the machine hesitated. The legal gentleman, with a red lump hoisting his damp hair in the exact middle of his forehead, hesitated. He looked down earnestly at Elisha.

“You know, there’s a proviso in those contracts. It says you can return the goods and select anything else from their catalogue. That’s fair enough. There’s watches and pens and things, I might, mebbe, hold onto them rings for a few days

Elisha walked on into the barn. He turned round and round in an empty stall and looked at it as though he had never seen it before.

Yodeled a voice behind him: “It’s time fur to milk the milk!”

Elisha for the first time failed to catch the pail as Adam tossed it to him. But it rolled with such grotesque purposefulness to his very feet that he smiled — crookedly.

Featured image: “I have here a certain legal dokiment which authorizes me to replevy two certain properties.”

Illustrations by Tony Sarg

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now