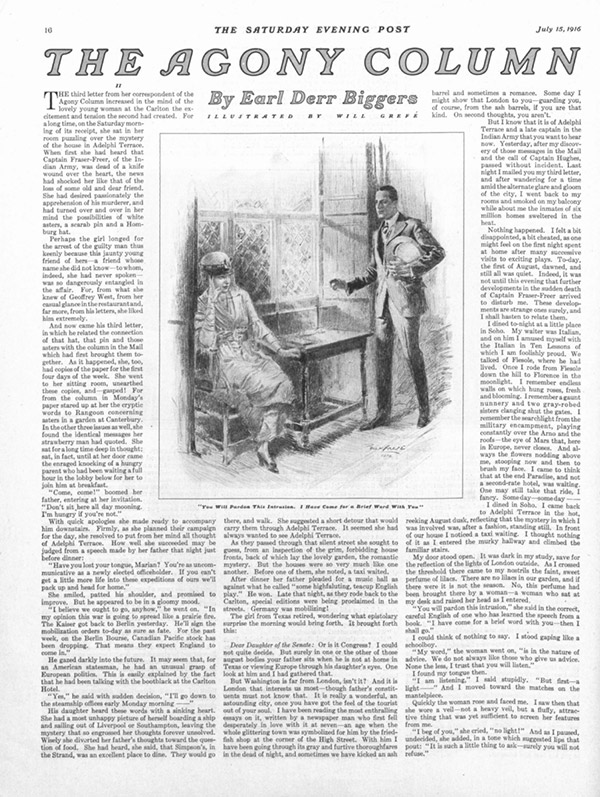

In part two of this classic crime serial, Earl Derr Biggers continues to weave a story of intrigue and deceit centered around a mysterious newspaper column. Biggers is most famous for his recurring fictional sleuth Charlie Chan as well as his popular novel Seven Keys to Baldplate, which was adapted into a Broadway stage play and later into multiple films.

Published on July 15, 1916

The third letter from her correspondent of the Agony Column increased in the mind of the lovely young woman at the Carlton the excitement and tension the second had created. For a long time, on the Saturday morning of its receipt, she sat in her room puzzling over the mystery of the house in Adelphi Terrace. When first she had heard that Captain Fraser-Freer, of the Indian Army, was dead of a knife wound over the heart, the news had shocked her like that of the loss of some old and dear friend. She had desired passionately the apprehension of his murderer, and had turned over and over in her mind the possibilities of white asters, a scarab pin and a Homburg hat.

Perhaps the girl longed for the arrest of the guilty man thus keenly because this jaunty young friend of hers — a friend whose name she did not know — to whom, indeed, she had never spoken — was so dangerously entangled in the affair. For, from what she knew of Geoffrey West, from her casual glance in the restaurant and, far more, from his letters, she liked him extremely.

And now came his third letter, in which he related the connection of that hat, that pin and those asters with the column in the Mail which had first brought them together. As it happened, she, too, had copies of the paper for the first four days of the week. She went to her sitting room, unearthed these copies, and — gasped! For from the column in Monday’s paper stared up at her the cryptic words to Rangoon concerning asters in a garden at Canterbury. In the other three issues as well, she found the identical messages her strawberry man had quoted. She sat for a long time deep in thought; sat, in fact, until at her door came the enraged knocking of a hungry parent who had been waiting a full hour in the lobby below for her to join him at breakfast.

“Come, come!” boomed her father, entering at her invitation. “Don’t sit here all day mooning. I’m hungry if you’re not.”

With quick apologies she made ready to accompany him downstairs. Firmly, as she planned their campaign for the day, she resolved to put from her mind all thought of Adelphi Terrace. How well she succeeded may be judged from a speech made by her father that night just before dinner:

“Have you lost your tongue, Marian? You’re as uncommunicative as a newly elected officeholder. If you can’t get a little more life into these expeditions of ours we’ll pack up and head for home.”

She smiled, patted his shoulder, and promised to improve. But he appeared to be in a gloomy mood.

“I believe we ought to go, anyhow,” he went on. “In my opinion this war is going to spread like a prairie fire. The Kaiser got back to Berlin yesterday. He’ll sign the mobilization orders today as sure as fate. For the past week, on the Berlin Bourse, Canadian Pacific stock has been dropping. That means they expect England to come in.”

He gazed darkly into the future. It may seem that, for an American statesman, he had an unusual grasp of European politics. This is easily explained by the fact that he had been talking with the bootblack at the Carlton Hotel.

“Yes,” he said with sudden decision, “I’ll go down to the steamship offices early Monday morning — ”

His daughter heard these words with a sinking heart. She had a most unhappy picture of herself boarding a ship and sailing out of Liverpool or Southampton, leaving the mystery that so engrossed her thoughts forever unsolved. Wisely she diverted her father’s thoughts toward the question of food. She had heard, she said, that Simpson’s, in the Strand, was an excellent place to dine. They would go there, and walk. She suggested a short detour that would carry them through Adelphi Terrace. It seemed she had always wanted to see Adelphi Terrace.

As they passed through that silent street she sought to guess, from an inspection of the grim, forbidding house fronts, back of which lay the lovely garden, the romantic mystery. But the houses were so very much dike one another. Before one of them, she noted, a taxi waited.

After dinner her father pleaded for a music hall as against what he called “some highfaluting, teacup English play.” He won. Late that night, as they rode back to the Carlton, special editions were being proclaimed in the streets. Germany was mobilizing!

The girl from Texas retired, wondering what epistolary surprise the morning would bring forth. It brought forth this:

Dear Daughter of the Senate:

Or is it Congress? I could not quite decide. But surely in one or the other of those august bodies your father sits when he is not at home in Texas or viewing Europe through his daughter’s eyes. One look at him and I had gathered that.

But Washington is far from London, isn’t it? And it is London that interests us most — though father’s constituents must not know that. It is really a wonderful, an astounding city, once you have got the feel of the tourist out of your soul. I have been reading the most enthralling essays on it, written by a newspaper man who first fell desperately in love with it at seven — an age when the whole glittering town was symbolized for him by the fried fish shop at the corner of the High Street. With him I have been going through its gray and furtive thoroughfares in the dead of night, and sometimes we have kicked an ash barrel and sometimes a romance. Someday I might show that London to you — guarding you, of course, from the ash barrels, if you are that kind. On second thoughts, you aren’t.

But I know that it is of Adelphi Terrace and a late captain in the Indian Army that you want to hear now. Yesterday, after my discovery of those messages in the Mail and the call of Captain Hughes, passed without incident. Last night I mailed you my third letter, and after wandering for a time amid the alternate glare and gloom of the city, I went back to my rooms and smoked on my balcony while about me the inmates of six million homes sweltered in the heat.

Nothing happened. I felt a bit disappointed, a bit cheated, as one might feel on the first night spent at home after many successive visits to exciting plays. Today, the first of August, dawned, and still all was quiet. Indeed, it was not until this evening that further developments in the sudden death of Captain Fraser-Freer arrived to disturb me. These developments are strange ones surely, and I shall hasten to relate them.

I dined tonight at a little place in Soho. My waiter was Italian, and on him I amused myself with the Italian in Ten Lessons of which I am foolishly proud. We talked of Fiesole, where he had lived. Once I rode from Fiesole down the hill to Florence in the moonlight. I remember endless walls on which hung roses, fresh and blooming. I remember a gaunt nunnery and two gray-robed sisters clanging shut the gates. I remember the searchlight from the military encampment, playing constantly over the Arno and the roofs — the eye of Mars that, here in Europe, never closes. And always the flowers nodding above me, stooping now and then to brush my face. I came to think that at the end Paradise, and not a second-rate hotel, was waiting. One may still take that ride, I fancy. Some day — some day —

I dined in Soho. I came back to Adelphi Terrace in the hot, reeking August dusk, reflecting that the mystery in which I was involved was, after a fashion, standing still. In front of our house I noticed a taxi waiting. I thought nothing of it as I entered the murky hallway and climbed the familiar stairs. My door stood open. It was dark in my study, save for the reflection of the lights of London outside. As I crossed the threshold there came to my nostrils the faint, sweet perfume of lilacs. There are no lilacs in our garden, and if there were it is not the season. No, this perfume had been brought there by a woman — a woman who sat at my desk and raised her head as I entered.

“You will pardon this intrusion,” she said in the correct, careful English of one who has learned the speech from a book. “I have come for a brief word with you — then I shall go.”

I could think of nothing to say. I stood gaping like a schoolboy.

“My word,” the woman went on, “is in the nature of advice. We do not always like those who give us advice. None the less, I trust that you will listen.”

I found my tongue then.

“I am listening,” I said stupidly. “But first — light.” And I moved toward the matches on the mantelpiece.

Quickly the woman rose and faced me. I saw then that she wore a veil — not a heavy veil, but a fluffy, attractive thing that was yet sufficient to screen her features from me.

“I beg of you,” she cried, “no light!” And as I paused, undecided, she added, in a tone which suggested lips that pout: “It is such a little thing to ask — surely you will not refuse.”

I suppose I should have insisted. But her voice was charming, her manner perfect, and that odor of lilacs reminiscent of a garden I knew long ago, at home.

“Very well,” said I.

“Oh — I am grateful to you,” she answered. Her tone changed. “I understand that, shortly after seven o’clock last Thursday evening, you heard in the room above you the sounds of a struggle. Such has been your testimony to the police?”

“It has,” said I.

“Are you quite certain as to the hour?” I felt that she was smiling at me. “Might it not have been later — or earlier?”

“I am sure it was just after seven,” I replied. “I’ll tell you why: I had just returned from dinner and while I was unlocking the door Big Ben on the House of Parliament struck — “

She raised her hand.

“No matter,” she said, and there was a touch of irony in her voice. “You are no longer sure of that. Thinking it over, you have come to the conclusion that it may have been barely six-thirty when you heard the noise of a struggle.”

“Indeed?” said I. I tried to sound sarcastic, but I was really too astonished by her tone.

“Yes — indeed!” she replied. “That is what you will tell Inspector Bray when next you see him. ‘It may have been six-thirty,’ you will tell him. ‘I have thought it over and I am not certain.”

“Even for a very charming lady,” I said, “I cannot misrepresent the facts in a matter so important. It was after seven — ”

“I am not asking you to do a favor for a lady,” she replied. “I am asking you to do a favor for yourself. If you refuse the consequences may be most unpleasant.”

“I’m rather at a loss — ” I began.

She was silent for a moment. Then she turned and I felt her looking at me through the veil.

“Who was Archibald Enright?” she demanded. My heart sank. I recognized the weapon in her hands. “The police,” she went on, “do not yet know that the letter of introduction you brought to the captain was signed by a man who addressed Fraser-Freer as Dear Cousin, but who is completely unknown to the family. Once that information reaches Scotland Yard, your chance of escaping arrest is slim.

“They may not be able to fasten this crime upon you, but there will be complications most distasteful. One’s liberty is well worth keeping — and then, too, before the case ends, there will be wide publicity — ”

“Well?” said I.

“That is why you are going to suffer a lapse of memory in the matter of the hour at which you heard that struggle. As you think it over, it is going to occur to you that it may have been six-thirty, not seven. Otherwise — ”

“Go on.”

“Otherwise the letter of introduction you gave to the captain will be. sent anonymously to Inspector Bray.”

“You have that letter!” I cried.

“Not I,” she answered. “But it will be sent to Bray. It will be pointed out to him that you were posing under false colors. You could not escape!”

I was most uncomfortable. The net of suspicion seemed closing in about me. But I was resentful, too, of the confidence in this woman’s voice.

“Nonetheless,” said I, “I refuse to change my testimony. The truth is the truth — ”

The woman had moved to the door. She turned.

“Tomorrow,” she replied, “it is not unlikely you will see Inspector Bray. As I said, I came here to give you advice. You had better take it. What does it matter — a half hour this way or that? And the difference is prison for you. Good night.”

She was gone. I followed into the hall. Below, in the street, I heard the rattle of her taxi.

I went back into my room and sat down. I was upset, and no mistake. Outside my windows the continuous symphony of the city played on — the busses, the trams, the never-silent voices. I gazed out. What a tremendous acreage of dank brick houses and dank British souls! I felt horribly alone. I may add that I felt a bit frightened, as though that great city were slowly closing in on me.

Who was this woman of mystery? What place had she held in the life — and perhaps in the death — of Captain Fraser-Freer? Why should she come boldly to my rooms to make her impossible demand?

I resolved that, even at the risk of my own comfort, I would stick to the truth. And to that resolve I would have clung had I not shortly received another visit — this one far more inexplicable, far more surprising, than the first.

It was about nine o’clock when Walters tapped at my door and told me two gentlemen wished to see me. A moment later into my study walked Lieutenant Norman Fraser-Freer and a fine old gentleman with a face that suggested some faded portrait hanging on an aristocrat’s wall. I had never seen him before.

“I hope it is quite convenient for you to see us,” said young Fraser-Freer.

I assured him that it was. The boy’s face was drawn and haggard; there was terrible suffering in his eyes, yet about him hung, like a halo, the glory of a great resolution.

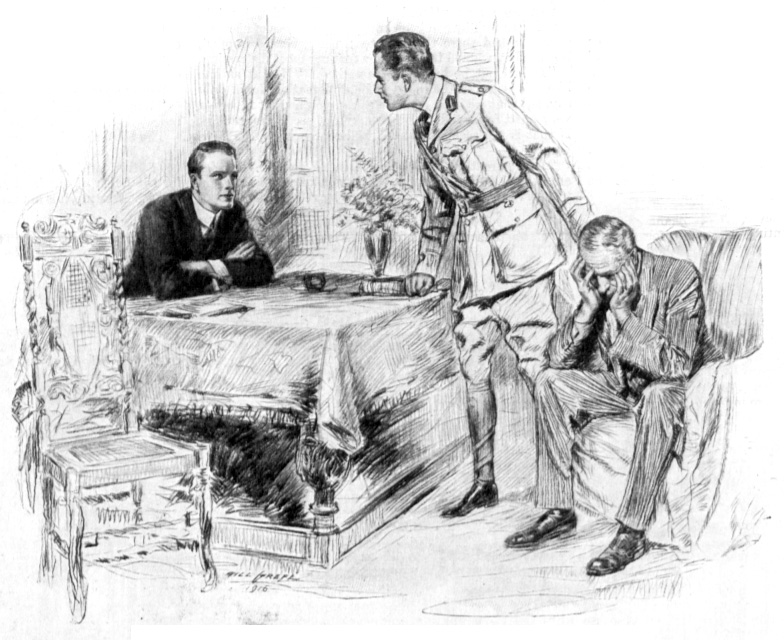

“May I present my father?” he said. “General Fraser-Freer, retired. We have come on a matter of supreme importance. The old man muttered something I could not catch.”

I could see that he had been hard hit by the loss of his elder son. I asked them to be seated; the general complied, but the boy walked the floor in a manner most distressing.

“I shall not be long,” he remarked. “Nor at a time like this is one in the mood to be diplomatic. I will only say, sir, that we have come to ask of you a great favor — a very great favor indeed. You may not see fit to grant it. If that is the case we cannot well reproach you. But if you can —”

“It is a great favor, sir!” broke in the general. “And I am in the odd position where I do not know whether you will serve me best by granting it or by refusing to do so.”

“Father — please — if you, don’t mind — ” The boy’s voice was kindly but determined. He turned to me.

“Sir — you have testified to the police that it was a bit past seven when you heard in the room above the sounds of the struggle which — which — You understand.”

In view of the mission of the caller who had departed a scant hour previously, the boy’s question startled me.

“Such was my testimony,” I answered. “It was the truth.”

“Naturally,” said Lieutenant Fraser-Freer. “Buter — as a matter of fact, we are here to ask that you alter your testimony. Could you, as a favor to us who have suffered so cruel a loss — a favor we should never forget — could you not make the hour of that struggle half after six?”

I was quite overwhelmed. “Your — reasons?” I managed at last to ask.

“I am not able to give them to you in full,” the boy answered. “I can only say this: It happens that at seven o’clock last Thursday night I was dining with friends at the Savoy — friends who would not be likely to forget the occasion.”

The old general leaped to his feet.

“Norman,” he cried, “I cannot let you do this thing! I simply will not — ”

“Hush, father,” said the boy wearily. “We have threshed it all out. You have promised — ”

The old man sank back into the chair and buried his face in his hands.

“If you are willing to change your testimony,” young Fraser-Freer went on to me, “I shall at once confess to the police that it was I who — who murdered my brother. They suspect me. They know that late last Thursday afternoon I purchased a revolver, for which, they believe, at the last moment I substituted the knife. They know that I was in debt to him; that we had quarreled about money matters; that by his death I, and I alone, could profit.”

He broke off suddenly and came toward me, holding out his arms with a pleading gesture I can never forget.

“Do this for me!” he cried. “Let me confess! Let me end this whole horrible business here and now.”

Surely no man had ever to answer such an appeal before.

“Why?” I found myself saying, and over and over I repeated it — “Why? Why?”

The lieutenant faced me, and I hope never again to see such a look in a man’s eyes.

“I loved him!” he cried. “That is why. For his honor, for the honor of our family, I am making this request of you. Believe me, it is not easy. I can tell you no more than that. You knew my brother?”

“Slightly.”

“Then, for his sake — do this thing I ask.”

“But — murder — ”

“You heard the sounds of a struggle. I shall say that we quarreled — that I struck in self defense.” He turned to his father. “It will mean only a few years in prison — I can bear that!” he cried. “For the honor of our name!”

The old man groaned, but did not raise his head. The boy walked back and forth over my faded carpet like a lion caged. I stood wandering what answer I should make.

“I know what you are thinking,” said the lieutenant. “You cannot credit your ears. But you have heard correctly. And now — as you might put it — it is up to you. I have been in your country.” He smiled pitifully. “I think I know you Americans. You are not the sort to refuse a man when he is sore beset — as-I am.”

I looked from him to the general and back again.

“I must think this over,” I answered, my mind going at once to Colonel Hughes. “Later — say tomorrow — you shall have my decision.”

“Tomorrow,” said the boy, “we shall both be called before. Inspector Bray. I shall know your answer then — and I hope with all my heart it will be yes.”

There were a few mumbled words of farewell and he and the broken old man went out. As soon as the street door closed behind them I hurried to the telephone and called a number Colonel Hughes had given me. It was with a feeling of relief that I heard his voice come back over the wire. I told him I must see him at once. He replied that by a singular chance he had been on the point of starting for my rooms.

In the half hour that elapsed before the coming of the colonel I walked about like a man in a trance. He was barely inside my door when I began pouring out to him the story of those two remarkable visits. He made little comment on the woman’s call beyond asking me whether I could describe her; and he smiled when I mentioned lilac perfume. At mention of young Fraser-Freer’s preposterous request he whistled.

“By gad!” he said. “Interesting — most interesting! I am not surprised, however. That boy has the stuff in him.”

“But what shall I do?” I demanded.

Colonel Hughes smiled. “It makes little difference what you do,” he said.

“Norman Fraser-Freer did not kill his brother, and that will be proved in due time.”

He considered for a moment. “Bray no doubt would be glad to have you alter your testimony, since he is trying to fasten the crime on the young lieutenant. On the whole, if I were you, I think that when the opportunity comes tomorrow I should humor the inspector.”

“You mean — tell him I am no longer certain as to the hour of that struggle?”

“Precisely. I give you my word that young Fraser-Freer will not be permanently incriminated by such an act on your part. And incidentally you will be aiding me.”

“Very well,” said I. “But I don’t understand this at all.”

“No — of course not. I wish I could explain to you; but I cannot. I will say this — the death of Captain Fraser-Freer is regarded as a most significant thing by the War Office. Thus it happens that two distinct hunts for his assassin are underway — one conducted by Bray, the other by me. Bray does not suspect that I am working on the case and I want to keep him in the dark as long as possible.

You may choose which of these investigations you wish to be identified with.”

“I think,” said I, “that I prefer you to Bray.”

“Good boy!” he answered. “You have not gone wrong. And you can do me a service this evening, which is why I was on the point of coming here, even before you telephoned me. I take it that you remember and could identify the chap who called himself Archibald Enwright — the man who gave you that letter to the captain.”

“I surely could,” said I. “Then, if you can spare me an hour, get your hat.”

And so it happens, lady of the Carlton, that I have just been to Limehouse. You do not know where Limehouse is and I trust you never will. It is picturesque; it is revolting; it is colorful and wicked. The weird odors of it still fill my nostrils; the sinister portrait of it is still before my eyes. It is the Chinatown of London — Limehouse. Down in the dregs of the town — with West India Dock Road for its spinal column — it lies, redolent of ways that are dark and tricks that are vain: Not only the heathen Chinee so peculiar shuffles through its dim-lit alleys, but the scum of the earth, of many colors and of many climes. The Arab and the Hindu, the Malayan and the Jan, black men from the Congo and fair men from Scandinavia — these you may meet there — the outpourings of all the ships that sail the Seven Seas. There many drunken beasts, with their pay in their pockets, seek each his favorite sin; and for those who love most the opium, there is, at all too regular intervals, the Sign of the Open Lamp.

We went there, Colonel Hughes and I. Up and down the narrow Causeway, yellow at intervals with the light from gloomy shops, dark mostly because of-tightly closed shutters through which only thin jets found their way, we walked until we came and stood at last in shadow outside the black doorway of Harry San Li’s so-called restaurant. We waited ten -minutes, fifteen minutes, and then a man came down the Causeway and paused before that door. There was something familiar in his jaunty walk. Then the faint glow of the lamp that was the indication of Harry San’s real business lit his pale face, and P knew that I had seen him last-in the cool evening at Interlaken, Where Limehouse could not have lived a moment, with the Jungfrau frowning down upon it.

“Enwright?” whispered Hughes. “Not a doubt of it!” said I.

“Good” he replied with fervor. And now another man shuffled down the street and stood suddenly straight and waiting before the colonel. “Stay with him,” said Hughes softly. “Don’t let him get out of your sight.”

“Good, sir,” said the man; and, saluting, he passed on up the stairs and whistled softly at that black, depressing door.

The clock above the Millwall Docks was striking eleven as the colonel and I caught a bus that should carry us back to a brighter, happier London. Hughes spoke but seldom on that ride; and, repeating his advice that I humor Inspector Bray on the morrow, he left me in the Strand.

So, my lady, here I sit in my study, waiting for that most important day that is shortly to dawn. A full evening, you must admit. A woman with the perfume of lilacs about her has threatened that unless I lie I shall encounter consequences most unpleasant. A handsome young lieutenant has begged me to tell that same lie for the honor of his family, and thus condemn him to certain arrest and imprisonment. And I have been down into hell tonight and seen Archibald Enwright, of Interlaken, conniving with the devil.

I presume I should go to bed; but I know I cannot sleep. Tomorrow is to be, beyond all question, a red letter day in the matter of the captain’s murder. And once again, against my will, I am down to play a leading part.

The symphony of this great, gray, sad city is a mere hum in the distance now, for it is nearly midnight. I shall mail this letter to you — post it, I should say, since I am in London — and then I shall wait in my dim rooms for the dawn. And as I wait I shall be thinking not always of the captain, or his brother, or of Hughes, or Limehouse and Enwright, but often — oh, very often — of you.

In my last letter I scoffed at the idea of a great war. But when we came back from Limehouse tonight the papers told us that the Kaiser had signed the order to mobilize. Austria in; Serbia in; Germany, Russia and France in. Hughes tells me that England is shortly to follow, and I suppose there is no doubt of it. It is a frightful thing — this future that looms before us; and I pray that for you at least it may hold only happiness.

For, ray-lady, when I write good night, I speak it aloud as I write; and there is in my voice more than I dare tell you of now.

THE AGONY COLUMN MAN.

Not unwelcome to the violet eyes of the girl from Texas were the last words of this letter, read in her room that Sunday morning. But the lines predicting England’s early entrance into the war recalled to her mind a most undesirable contingency. On the previous night, when the war extras came out confirming the forecast of his favorite bootblack, her usually calm father had shown signs of panic. He was not a man slow to act. And she knew that, putty though he was in her hands in matters which he did not regard as important, he could also be firm where he thought firmness necessary. America looked even better to him than usual, and he had made-up his mind to go there immediately. There was no use in arguing with him.

At this point came a knock at her door and her father entered. One look at his face — red, perspiring and decidedly unhappy — served to cheer his daughter.

“Been down to the steamship offices,” he panted, mopping his bald head. “They’re open today, just like it was a weekday — but they might as well be closed. There’s nothing doing. Every boat’s booked up to the rails and we can’t get out of here for two weeks — maybe more.”

“I’m sorry,” said his daughter.

“No, you ain’t! You’re delighted. You think it’s romantic to get caught like this. Wish I had the enthusiasm of youth.” He fanned himself with a newspaper. “Lucky I went over to the express office yesterday and loaded up on gold. I reckon when the blow falls it’ll be tolerable hard to cash checks in this man’s town.”

“That was a good idea.”

“Ready for breakfast?” he inquired.

“Quite ready,” she smiled.

They went below, she humming a song from a revue, while he glared at her. She was very glad they were to be in London a little longer. She felt she could not go, with that mystery still unsolved.

The last peace Sunday London was to know in many weary months went by, a tense and anxious day. Early on Monday the fifth letter from the young man of the Agony Column arrived, and when the girl from Texas read it she knew that under no circumstances could she leave London now. It ran:

Dear Lady from Home:

I call you that because the word home has for me, this hot afternoon in London, about the sweetest sound word ever had. I can see, when I close my eyes, Broadway at midday; Fifth Avenue, gay and colorful, even with all the best people away; Washington Square, cool under the trees, lovely and desirable despite the presence everywhere of alien neighbors from the district to the South. I long for home with an ardent longing; never was London so cruel, so hopeless, so drab, in ink eyes. For, as I write this, a constable sits at my elbow, and he and I are shortly to start for Scotland Yard: I have been arrested as a suspect in the case of Captain Fraser-Freer’s murder!

I predicted last night that this was to be a red letter day in the history of that case, and I also saw myself an unwilling actor in the drama. But little did I suspect the series of astonishing events that was to come with the morning; little did I dream that the net I have been dreading would today engulf me. I can scarcely blame Inspector Bray for holding me; what I cannot understand is why Colonel Hughes —

But you want, of course, the whole story from the beginning; and I shall give it to you. At eleven o’clock this morning a constable called on me at my rooms and informed me that I was wanted at once by the Chief Inspector at the Yard.

We climbed — the constable and I — a narrow stone stairway somewhere at the back of New Scotland Yard, and so came to the inspector’s room. Bray was waiting for us, smiling and confident. I remember — silly as the detail is — that he wore in his buttonhole a white rose. His manner of greeting me was more genial than usual. He began by informing me that the police had apprehended the man who, they believed, was guilty of the captain’s murder.

“There is one detail to be cleared up,” he said. “You told me the other night that it was shortly after seven o’clock when you heard the sounds of struggle in the room above you. You were somewhat excited at the time, and under similar circumstances men have been known to make mistakes. Have you considered the matter since? Is it not possible that you were in error in regard to the hour?”

I recalled Hughes’ advice to humor the inspector; and I said that; having thought it over, I was not quite sure. It might have been earlier than seven — say six-thirty.

“Exactly,” said Bray. He seemed rather pleased. “The natural stress of the moment — I understand. Wilkinson, bring in your prisoner.”

The constable addressed turned and left the room, coming back a moment later with Lieutenant Norman Fraser-Freer. The boy was pale; I could see at a glance that he had not slept for several nights.

“Lieutenant,” said Bray very sharply, “will you tell me — is it true that your brother, the late captain, had loaned you a large sum of money a year or so ago?”

“Quite true,” answered the lieutenant in a low voice.

“You and he had quarreled about the amount of money you spent? Yes!”

“By his death you became the sole heir of your father, the general. Your position with the money-lenders was quite altered. Am I right?”

“I fancy so.”

“Last Thursday afternoon you went to the Army and Navy Stores and-purchased a revolver. You already had your service weapon, but to shoot a man with a bullet from that would be to make the hunt of the police for the murderer absurdly simple.

The boy made no answer.

“Let us suppose,” Bray went on, “that last Thursday evening at half after six you called on your brother in his rooms at Adelphi Terrace. There was an argument about money. You became enraged. You saw him and him alone between you and the fortune you needed so badly. Then — 1 am only supposing — you noticed on his table an odd knife he had brought from India — safer — more silent — than a gun. You seized it — ”

“Why suppose?” the boy broke in. “I’m not trying to conceal anything. You’re right — I did it! I killed my brother! Now let us get the whole business over as soon as may be.”

Into the face of Inspector Bray there came at that moment a look that has been puzzling me ever since — a look that has recurred to my mind again and again, even in the stress and storm of this eventful day. It was only too evident that this confession came to him as a shock. I presume so easy a victory seemed hollow to him; he was wishing the boy had put up a fight. Policemen are probably that way.

“My boy,” he said, “I am sorry for you. My course is clear. If you will go with one of my men — ”

It was at this point that the door of the inspector’s room opened and Colonel Hughes, cool and smiling, walked in. Bray chuckled at the sight of the military man.

“Ah, colonel,” he cried, “you make a good entrance! This morning, when I discovered I had the honor of having you associated with me in the search for the captain’s murderer, you were foolish enough to make a little wager

“I remember,” Hughes answered. “A scarab pin against — a Homburg hat.”

“Precisely,” said Bray. “You wagered that you, and not I, would discover the guilty man. Well, colonel, you owe me a scarab. Lieutenant Norman Fraser-Freer has just told me that he killed his brother, and I was on the point of taking down his full confession.”,

“Indeed!” replied Hughes calmly. “Interesting — most interesting! But before we consider the wager lost — before you force. the lieutenant to confess in full — I should like the floor.”

“Certainly,” smiled Bray.

“When you were kind enough to let me have two of your men this morning,” said Hughes, “I told you I contemplated the arrest of a lady. I have brought that lady to Scotland Yard with me.” He stepped to the door, opened it and beckoned. A tall, blond, handsome woman of about thirty-five entered; and instantly to my nostrils came the pronounced odor of lilacs. “Allow me, inspector,” went on the colonel, “to introduce to you the Countess Sophie de Graf, late of Berlin, late of Delhi and Rangoon, now of 17 Leitrim Grove, Battersea Park Road.”

The woman faced Bray; and there was a terrified, hunted look in her eyes.

“You are the inspector?” she asked. “I am,” said Bray.

“And a man — I can see that,” she went on, her eyes flashing angrily at Hughes. “I appeal to you to protect me from the brutal questioning of this — this fiend.”

“You are hardly complimentary, countess,” Hughes smiled. “But I am willing to forgive you if you will tell the inspector the story that you have recently related to me.”

The woman shut her lips tightly and for a long moment gazed into the eyes of Inspector Bray.

“He” — she said at last, nodding in the direction of Colonel Hughes — “he got it out of me — how, I don’t know.”

“Got what out of you?” Bray’s little eyes were blinking.

“At six-thirty o’clock last Thursday evening,” said the woman, “I went to the rooms of Captain Fraser-Freer, in Adelphi Terrace. An argument arose. I seized from his table an Indian dagger that was lying there — I stabbed him just above the heart!”

In that room in Scotland Yard a tense silence fell. For the first time we were all conscious of the tiny clock on the inspector’s desk, for it ticked now with a loudness sudden and startling. I gazed at the faces about me. Bray’s showed a momentary surprise — then the mask fell again. Lieutenant Fraser-Freer was plainly amazed. On the face of Colonel Hughes I saw what struck me as an open sneer.

“Go on, countess,” he smiled.

She shrugged her shoulders and turned toward him a disdainful back. Her eyes were all for Bray.

“It’s very brief, the story,” she said hastily — I thought almost apologetically. “I had known the captain in Rangoon. My husband was in business there — an exporter of rice — and Captain Fraser-Freer came often to our house. We — he was a charming man, the captain — “

“Go on!” ordered Hughes.

“We fell desperately in love,” said the countess. “When he returned to England, though supposedly on a furlough, he told me he would never return to Rangoon. He expected a transfer to Egypt. So it was arranged that I should desert my husband and follow on the next boat. I did so — believing in the captain — thinking he really cared for me — I gave up everything for him. And then her voice broke and she took out a handkerchief. Again that odor of lilacs in the room.

“For a time I saw the captain often in London; and then I began to notice a change. Back among his own kind, with the lonely days in India a mere memory — he seemed no longer to — to care for me. Then — last Thursday morning — he called on me to tell me that he was through; that he would never see me again — in fact, that he was to marry a girl of his own people who had been waiting.

The woman looked piteously about at us.

“I was desperate,” she pleaded. “I had given up all that life held for me — given it up for a man who now looked at me coldly and spoke of marrying another. Can you wonder that I went in the evening to his rooms — went to plead with him — to beg, almost on my knees? It was no use. He was done with me — he said that over and over. Overwhelmed with blind rage and despair, I snatched up that knife from the table and plunged it into his heart. At once I was filled with remorse.

“One moment,” broke in Hughes. “You may keep the details of your subsequent actions until later. I should like to compliment you, countess. You tell it better each time.”

He came over and faced Bray. I thought there was a distinct note of hostility in his voice.

“Checkmate, inspector!” he said.

Bray made no reply. He sat there staring up at the colonel, his face turned to stone.

“The scarab pin,” went on Hughes, “is not yet forthcoming. We are tied for honors, my friend. You have your confession, but I have one to match it.”

“All this is beyond me,” snapped Bray.

“A bit beyond me, too,” the colonel answered. “Here are two people who wish us to believe that on the evening of Thursday last, at half after six of the clock, each sought out Captain Fraser-Freer in his rooms and murdered him.”

He walked to the window and then wheeled dramatically.

“The strangest part of it all is,” he added, “that at six-thirty o’clock last Thursday evening, at an obscure restaurant in Soho — Frigacci’s — these two people were having tea together!”

I must admit that, as the colonel calmly offered this information, I suddenly went limp all over at a realization of the endless maze of mystery in which we were involved. The woman gave a little cry and Lieutenant Fraser-Freer leaped to his feet.

“How the devil do you know that?” he cried.

“I know it,” said Colonel Hughes, “because one of my men happened to be having tea at a table nearby. He happened to be having tea there for the reason that ever since the arrival of this lady in London, at the request of her friends in India, I have been keeping track of her every move; just as I kept watch over your late brother, the captain.”

Without a word Lieutenant Fraser-Freer dropped into a chair and buried his face in his hands.

“I’m sorry, my son,” said Hughes. “Really, I am. You made a heroic effort to keep the facts from coming out — a man’s-size effort it was. But the War Office knew long before you did that your brother had succumbed to this woman’s lure — that he was serving her and Berlin, and not his own country, England.”

Fraser-Freer raised his head. When he spoke there was in his voice an emotion vastly more sincere than that which had moved him when he made his absurd confession.

“The game’s up,” he said. “I have done all I could. This will kill my father, I am afraid. Ours has been an honorable name, colonel; you know that — a long line of military men whose loyalty to their country has never before been in question. I thought my confession would end the whole nasty business, that the investigations would stop, and that I might be able to keep forever unknown this horrible thing about him — about my brother.”

Colonel Hughes laid his hand on the boy’s shoulder, and the latter went on:

“They reached me — those frightful insinuations about Stephen — in a roundabout way; and when he came home from India I resolved to watch him. I saw him go often to the house of this woman. I satisfied myself that she was the same one involved in the stories coming from Rangoon; then, under another name; I managed to meet her. I hinted to her that I myself was none too loyal; not completely, but to a limited extent, I won her confidence. Gradually I became convinced that my brother was indeed disloyal to his country, to his name, to us all. It was at that tea time you have mentioned when I finally made up my mind. I had already bought a revolver; and, with it in my pocket, I went to the Savoy for tea.”

He rose and paced the floor.

“After tea I went to Stephen’s rooms. I was resolved to have it out with him, to put the matter to him bluntly; and if he had no explanation to give me I intended to kill him then and there. So, you see, I was guilty in intention if not in reality. I entered his study. It was filled with strangers. On his sofa I saw my brother Stephen lying — stabbed above the heart — dead!” There was a moment’s silence. “That is all,” said Lieutenant Fraser-Freer.

“I take it,” said Hughes kindly, “that we have finished with the lieutenant. Eh, inspector?”

“Yes,” said Bray shortly. “You may go.”

“Thank you,” the boy answered. As he went out he said brokenly to Hughes: “I must find him — my father.”

Bray sat in his chair, staring hard ahead, his jaw thrust out angrily. Suddenly he turned on Hughes.

“You don’t play fair,” he said. “I wasn’t told anything of the status of the captain at the War Office. This is all news to me.”

“Very well,” smiled Hughes. “The bet is off if you like.”

“No, by heaven!” Bray cried. “It’s still on, and I’ll win it yet. A fine morning’s work I suppose you think you’ve done. But are we any nearer to finding the murderer? Tell me that.”

“Only a bit nearer, at any rate,” replied Hughes suavely. “This lady, of course, remains in custody.”

“Yes, yes,” answered the inspector. “Take her away!” he ordered.

A constable came forward for the countess and Colonel Hughes gallantly held open the door.

“You will have an opportunity, Sophie,” he said, “ to think up another story. You are clever — it will not be hard.”

She gave him a black look and went out. Bray got up from his desk. He and Colonel Hughes stood facing each other across a table, and to me there was something in the manner of each that suggested eternal conflict.

“Well?” sneered Bray.

“There is one possibility we have overlooked,” Hughes answered. He turned toward me and I was startled by the coldness in his eyes. “Do you know, inspector,” he went on, “that this American came to London with a letter of introduction to the captain — a letter from the captain’s cousin, one Archibald Enwright? And do you know that Fraser-Freer had no cousin of that name?”

“No!” said Bray.

“It happens to be the truth,” said Hughes. “The American has confessed as much to me.”

“Then,” said Bray to me, and his little blinking eyes were on me with a narrow calculating glance that sent the shivers up and down my spine, “you are under arrest. I have exempted_ so far because of your friend at the United States consulate. That exemption ends now.”

I was thunderstruck. I turned to the colonel, the man who had suggested that I seek him out if I needed a friend — the man I had looked to save me from just such a contingency as this. But his eyes were quite fishy and unsympathetic.

“Quite correct, inspector,” he said. “Lock him up!” And as I began to protest he passed very close to me and spoke in a low voice: “Say nothing. Wait!”

I pleaded to be allowed too back to my rooms, to communicate with my friends, and pay a visit to our consulate and to the Embassy; and at the colonel’s suggestion Bray agreed to this somewhat irregular course. So this afternoon I have been abroad with a constable, and while I wrote this long letter to you he has been fidgeting in my easy-chair. Now he informs me that his patience is exhausted and that I must go at once.

So there is no time to wonder; no time to speculate as to the future, as to the colonel’s sudden turn against me or the promise of his whisper in my ear. I shall, no doubt, spend the night behind those hideous, forbidding walls that your guide has pointed out to you as New Scotland Yard. And when I shall write again, when I shall end this series of letters so filled with

The constable will not wait. He is as impatient as a child. Surely he is lying when he says I have kept him here an hour.

Wherever I am, dear lady, whatever be the end of this amazing tangle, you may be sure the thought of you

Confound the man!

YOURS, IN DURANCE VILE.

TO BE CONTINUED

Featured image: “You will pardon this intrusion. I have come for a brief word with you.” (Illustrated by Will Grefé / SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now