Claud Cockburn first received acclaim for his work as a journalist in England during the 1930s. He became most famous, however, for his affiliation with the British Communist Party during the Cold War. To avoid unwanted press, Cockburn began writing under the pseudonym James Helvick. He used the name to publish a number of works, including his 1951 novel Beat the Devil and the following story printed in the Post.

Published on October 17, 1959

A couple of ounces of pure, unblended English rain slid off the extended leaves of a wizened oak tree and struck Francis Manning just above the back of his collar.

“To think,” he said, “that that tree has been waiting to do that to me since the time of William the Conqueror.”

Nancy Manning said, “Hush, you’ll disturb the game.”

Francis Manning said, “Did you say game?” He looked at his wife sternly, but she continued to focus on the cricketers. Her expression was one of reverent attention. She was thinking about Sir Arthur Ludd.

Francis thought about him, too, with mingled awe, resentment and censure. He was irritably aware that it was this Ludd who, by remote control, had guided them and their daughter Francesca to the position in which they now found themselves — that is to say, England, inside a ruin, beside a lawn, on a bench, watching a cricket match.

During one of those regularly recurrent pauses — between what are called “overs” — which, as in Oriental music, are the very essence of cricket, Francis Manning said: “I yield to no man in my respect for Sir Arthur Ludd. I accept that he had the highest mind you or anyone else ever saw. I just want to say that there are times when I could wish you had never met him.”

He knew that this remark was unworthy of him, that he should no more criticize Nancy’s relationship with Sir Arthur Ludd than he would attack her for being moved by St. George, Sir Isaac Newton or the Charge of the Light Brigade. No fair-minded man could dare say that it was Sir Arthur Ludd’s fault that he had made such an impression upon Nancy all those years ago in blitztime England, where, by crude overstatements of her age and experience, she had promoted herself a tiny uniformed job ministering to the American Forces at Rainbow Corner and other relief points. Nor could you fault Nancy on account of the deep and lasting emotions aroused in her by this dedicated baronet, wounded at Dunkirk, invalided, an occasional lecturer to troops on technical aspects of warfare. It was in this capacity that he had first met Nancy. But he had also been immediately welcomed to the laboratories and back rooms of the Ministries of Aviation and Supply, where the brightest and most profound of Britain’s technicians were winning the war. Knowledgeable people said he was the brightest and most profound of them all. He also knew the work of the Restoration Dramatists by heart, and for relaxation used to translate them into Aristophanic Greek.

Nancy looked at her husband, saying nothing, for fear of disturbing the hush of the cricket field, but telling him with her beautiful eyes that he had said a coarse and hurtful thing. She had never concealed her feelings about Sir Arthur Ludd. Her memories of him during those months in England were not guilty but ennobling. She had made it clear when she married Francis that she intended to bring these memories along, together with a few pieces of fine furniture and glassware from her old family home in Vermont. Far from cluttering their Manhattan apartment, they would all serve to lend it a note of dignity.

And indeed the wraith of Sir Arthur had in one sense behaved itself unobtrusively. He was rarely spoken of. But one was made sharply aware that from time to time Nancy pursued one train of thought or course of action, rather than another, because she felt it to be in line with the ideals of Ludd. And sometimes when she criticized Francis, and later their daughter Francesca, Francis and Francesca instinctively knew that they must have done something or expressed some thought of a definitely un-Ludd nature.

It was unquestionably “Luddism” — as Francis referred to it when vexed — which had made up Nancy’s mind that this year they would go to England for the summer. At seventeen, Francesca did not seem always apt to appreciate the sort of things Sir Arthur Ludd “stood for.”

He stood for the real England. Not, as Nancy emphasized, that he had been narrow-minded. He had stood, as she recalled, for the real France and the real America too. These were all hard to find. You needed rigorous mental and spiritual training to get to them.

A determined trek to the real England would, Nancy said, do Francesca, and indeed all of them, a world of good. It would lift them, she implied, up toward the Ludd standard. It would be a gesture toward the higher values. Because Francis and Francesca had both chanced to be thinking in terms of Maine, the intervention of the unseen hand of Ludd in their holiday plans seemed particularly irksome.

To Jay Porter, who found himself sitting here damply with the three Mannings watching this cricket, the ghostly presence of Sir Arthur Ludd was even more oppressive. This youth Porter, from Indianapolis, being exposed temporarily to an Oxford education, had latched onto the Mannings while they were viewing Oxford at the end of the summer term. He had rejoiced to find himself at a table with fellow Americans in an overcrowded Oxford restaurant. He rejoiced further to note that one of these fellow citizens was a glorious girl gleaming at him only the table’s breadth away. There was conversation. There were introductions. Parents, in such circumstances, must be accepted as a necessary evil. Jay found the Mannings not evil at all. Yet there were times when he felt that the delightful Mrs. Manning was measuring him with her beautiful eyes against some invisible marking, and finding that he did not measure up.

He mentioned his impression to Francesca. “Probably it’s Ludd,” she said. “Maybe he finds you wanting — in nobility of character, high-mindedness, other-worldliness, strength of purpose, modesty, intellectual genius. Some je ne sais quoi that you don’t happen to have.”

“He’s a liar,” said Jay. “Who is he?”

Francesca explained about Sir Arthur Ludd.

“You don’t even know him?”

“Only mother does,” said Francesca. “But on a spiritual plane I’d say I’m well acquainted with him. I’m familiar with all his little ways.”

“And so it comes to pass,” said Jay, fixing her with burning eyes, “that under the dominance of this myth from the past, you trail about this country suffering experiences sometimes bizarre, sometimes merely horrible, and sometimes both at once, like this. Do you suppose, by the way, that this is the real England?”

“Nothing else was,” said Francesca, wriggling agreeably under the slither of the remaining raindrops over her skin. “People kept telling us ‘this isn’t the real England,’ and then we came to this historic township here with its castle famed in legend, and a cricket match going on and all. And if that isn’t the real England we’ll maybe have to throw in our hand.

“So there we all are,” said Jay, “poor hapless puppets in the hands of Ludd, the sadistic scientist from outer space.”

He sighed, continuing to gaze at Francesca. “You’re not keeping your mind on the game,” she said.

“Like a fish,” he said.

“Me? Like a fish?” Her voice rose to a small shriek. “I like that! Honestly — ”

“Like a fish out of water, I meant,” said Jay hurriedly. “Beautiful, gleaming and wriggling and all in the wrong environment and element.” He peered angrily around at the mackintoshed figures distributed sparsely about the benches.

“Well, mother thinks you’re an undesirable element,” said Francesca. “She feels we didn’t come here to pick up people like you that we could meet by the dozen back home.”

Nancy was turning to shush them again when an intense noise zipped across the playing field like a projectile and seemed to explode at the Mannings’ very feet. The players froze, then stared at the benches on the further side of the field. A moment later the noise was repeated. and this time was distinguishable as human speech.

“Nancy!” was the sound it made; and again, “Hi! Nancy!”

Looked at askance by the players, flaunting a raincoat like a cloak draped from the shoulders of a rowdy sports coat, a bulky figure came straight across the field in a swaggering hobble. From a distance of thirty yards the man began to wave enthusiastically and actually to converse, as though he were talking across the width of a drawing room.

“Nancy, my dear!” he shouted. “Ages since I saw you! What on earth have you been doing with yourself? How’ve you been? Awful lot of ’flu about this year, though mind you the reports may be exaggerated. Nothing to be frightened of.”

By this time he was clumsily hurdling the intervening benches. Members of the Manning party saw looming above them a shoe-leathery face, scarred here and there, it seemed, by a slip of the cobbler’s hand; a Roman nose protruding nobly from it; and eyes both roving and intent with a droop of the left eyelid that made you think of a pirate’s patch.

“Arthur!” said Nancy. “It’s just wonderful to see you. Francis, this is Sir Arthur Ludd. Arthur, this is my husband.”

“Splendid! Splendid!” said Sir Arthur. They started to make room for him on their bench, but he had already hobbled round it and seated himself on the bench immediately behind them.

“No use trying to talk now in this utter discomfort,” he said, leaning forward. “What we’ll do is, we’ll watch this thing for a bit and then we’ll all go and I mean to say as it were.”

Peering around for a moment, Jay saw him extend his legs and throw himself into a semisupine attitude, his arms extended in each direction along the back of the bench.

Francis, Francesca and Jay Porter turned their attention to the game in an awed silence. The personal materialization of Sir Arthur Ludd was as disconcerting as would be a sudden wave and cheery greeting from a symbolic statue on some public building. His presence immediately behind made them all feel that it was their duty to watch England’s national game with an increased semblance of interest.

The ecclesiastical quiet, briefly broken by the eruption of Sir Arthur, had again settled over the field, emphasized rather than shattered by the sound which, Jay was happy to remember, was properly known as the “crack of leather on willow.” The fans maintained an almost eerie silence, commenting on the game chiefly by nods, shakes of the head, and an occasional sigh as of scorn or despair.

“Surely,” whispered Jay to Francesca, “there’s a bit in this piece where someone calls out ‘Play up, and play the game!’ Or have I my facts wrong?”

He had not. At that very moment a hoarse voice shattered the moist peace with an abrupt staccato cry.

“Play up, and play the game!” was its utterance. It ceased, cut off as sharply as it had begun.

Electrified by this noise which came from immediately behind them, the Mannings and Jay Porter looked round. Sir Arthur Ludd was still in his partially recumbent position. His chin had fallen forward to rest on his gaudy tie, the snap brim of his hat almost covered his face. Some of the fans had turned round, too, in irritable curiosity, but there was nothing to connect Sir Arthur with that in spiriting exhortation.

Uneasily the spectators in front of him settled down to appreciate whatever was going on on the pitch. They did not settle for long. The shattering voice came again.

“Jolly well bowled, sir!” it suddenly shouted, “Jolly well bowled!”

Since the bowler was not in action at all at the moment, this piercing piece of applause struck spectators and players alike as painfully irrelevant. All gazed in the direction of Sir Arthur, but it was as though he had never moved. A man sitting next to him gave him an exasperated little nudge, and at the same time moved himself an inch or two away from him on the bench in a gesture of disassociation. Sir Arthur snapped up his chin and pushed his hat back on his head and looked about him with a lofty expression. The people who had been eying him censoriously quickly looked away again. He leaned forward and tapped Francis on the shoulder.

“I don’t know how you feel about it, old boy,” he said, “but it seems to me we’ve seen about enough of this. There’s a bar in the pavilion. Why don’t we all go and so to speak — ”

Nancy’s expression, as Sir Arthur led the way toward a chalet-type wooden building at the end of the field, said that this certainly was going to be a privilege.

“Mother looks,” said Francesca, “as though she was hoping for the best from us and expecting the worst.”

Grimly, Francis braced himself for some high-minded conversation. He felt it his duty to his wife to tell Francesca and Jay to brace themselves for the same. Francesca sighed. Jay Porter looked lovingly at her and glared at the swaggering raincoat ahead of them.

“J’ever hear,” Sir Arthur was saying as they filed into the pavilion, “that story I read somewhere about the man that died suddenly while watching a cricket match? Over three inches of rain had fallen for seven runs, and it was supposed the excitement killed him.” He laughed loudly. A party of Anglo-Englishmen at one end of the small bar displayed disgust at the unseemly jest. Two American airmen at the other end sniggered happily. Sir Arthur rounded on them.

“Just because,” he said sternly, “you people prefer playing rounders with a hard ball, there’s no occasion to sneer at our national game.”

“Well, anyway we paid to see it, didn’t we?” said one of the airmen.

“Not at all,” said Sir Arthur. “You paid to see these magnificent grounds and this historic castle, including its horrific dungeons and the boudoir where Henry VIII possibly made his first pass at Anne Boleyn. And then, today being Saturday, you’ve got the splendid display of cricket at its best thrown in. How much more, may I ask, do you expect for a lousy four shillings and sixpence, with just a very few extras here and there?” The airmen looked at him as unfavorable as did the English party at the other end of the bar.

“J’ever notice,” said Sir Arthur to Nancy, “that something about the game of cricket brings out the worst in everyone? Evil, sour expressions are what we see around a cricket ground. Though mind you,” he added loudly, “it may be of course that only sour and evil people ever go to watch such games.”

“But you were watching, Sir Arthur,” said Francesca. “You were shouting and encouraging them.”

“Wasn’t actually watching,” said Sir Arthur; “just sitting meditating, more or less contemplating my navel. But the crowd likes to hear a cry of ‘Well caught’ or something of the kind from time to time, so I give it them every so often.”

“But why do you come at all if that’s how you feel about it?”

“To make money,” said Sir Arthur. “Ever since I opened the castle grounds to the public I spend every Saturday at least padding about, helping to sort of, as it were. By all means buy us another big drink all round, Manning old man. As I say, it encourages the masses to see the owner in the flesh. People natter about the Duke of Bedford and that three-ring circus or whatever it is he runs at his place, but what I say is where else can you put down a mere four and six pence and be sure of seeing a baronet of ancient lineage and a brilliant scientist to boot?”

He slapped his hand on the bar and looked challengingly around at the company.

“So this is your place?” said Nancy. “I do admire your enterprise, but it must be sad having to sort of hire it out this way. I remember how you used to feel about the family traditions.”

“Comes to that,” said Sir Arthur, “the Ludds have always been in the looting line from way back. Looting and low cunning — that’s how we got the castle in the first place, changing sides at the right moment in the Wars of the Roses. I love to hear the jingle of the cash register behind the bar there, and the merry click of the turnstiles. I love money; don’t you, Manning?”

“Great stuff!” said Manning, in a tone hearty but bewildered.

“And of course the money goes to keeping up your laboratory,” said Nancy. “I read in a magazine somewhere that some o f your researches might ultimately save as many lives as penicillin.”

“Oh, I chisel most of the lab money out of the government,” said Sir Arthur. “Easy enough, you know, if you know where to start chiseling. Thank God, a little title and the old-school tie are still sometimes worth a bit more than honest merit. I spend most of what I make out of this castle racket on strictly personal luxuries — wine, really good cigars, you know, that type of thing.”

“And all the time,” breathed Nancy rather anxiously, “you may be on the verge of something that will save all those billions of lives.”

“Can’t say,” said Sir Arthur. “It’s a tossup. I’m the best man in England in my line, but even so it’s just a tossup. And by George! when one looks around at the citizenry one wonders whether there hasn’t been a bit too much life saving in the past. I intend no personal offense,” he added with an unctious smile at one of the Englishmen who seemed to be on the point of angry protest. “Dear Nancy, how happy I am to see you. Should we all take a little stroll round the place? I like to have a quick look round before closing time.”

Beside a path behind the pavilion an irregular semicircle of large stones was visible in the rank grass. A neatly painted notice said: “Possible site of Druid ring and altar. Here young maidens may have been bound shrieking on a midsummer’s night, and at dawn pitilessly sacrificed to the Sun God.”

“They may, at that,” said Sir Arthur.

“Is there historic evidence for it?” asked Jay.

“Naturally not,” said Sir Arthur. “We are dealing here with the prehistoric.”

Where the path adjoined a well-trodden dirt track a signpost announced: “To the camp for nudists.”

“A small idea I picked up from the Duke of Bedford again,” said Sir Arthur. “The papers were full of his plans for inviting one of the nudist societies to camp on his grounds.”

“I don’t know that I specially want to see a lot of nudists,” said Francesca, as they moved in the direction of the sign.

“You aren’t likely to,” said Sir Arthur. “It’s all right for Bedford down there by the muggy Thames, but I can’t see any society of nudists being fools enough to come up to a chilly rainswept place like this. I don’t want any charges of misrepresentation, and this, as the sign indicates to everyone of average intelligence, is simply a camp available to nudists should they wish to take advantage of it. Do any business today, Tom?” he inquired of an elderly man who was folding a small collapsible chair and preparing to leave his position in front of a low fence, enclosing what seemed to be an extensive copse where the undergrowth grew thick beneath the trees. “Tom,” explained Sir Arthur, “has the binocular concession here. Lets them out at a shilling a time for people who want to get a good view of any nudists there may happen to be.”

“Only six bob today, sir,” said the old man. “There ain’t the interest in the naked human form there used to be. I suppose the movies have damped the ardor, as you might say.”

“But if there aren’t any nudists there anyway?” said Jay.

“In my young days,” said the old man sternly, “we’d have paid our bob just on the off chance.” He looked Jay up and down with sad contempt and ambled away, the binoculars which had been in such poor demand bumping against his hip.

As they approached the castle itself, the last of the bedraggled visitors were leaving, complaining loudly among themselves at the extortionate price they had been asked for tea and buns. “Imagine that,” said Sir Arthur. “Complaining about a few bob extra for tea in such sur- roundings. Some of these people have no historic sense.”

“Rugged-looking old place,” commented Francis Manning.

“You bet it’s rugged,” said Sir Arthur. “I had to pay a gang of workmen a packet to knock it about till it got the proper fifteenth-century tone. Actually, most of it was run up less than a hundred years ago by my great-grandfather when he made a bit of money out of a small coal mine he chanced to find. At that, he forgot battlements. Had to put them on myself. In my opinion to invite the public to a castle that has no battlements is equivalent to obtaining money under false pretenses. It’s the same with dungeons.”

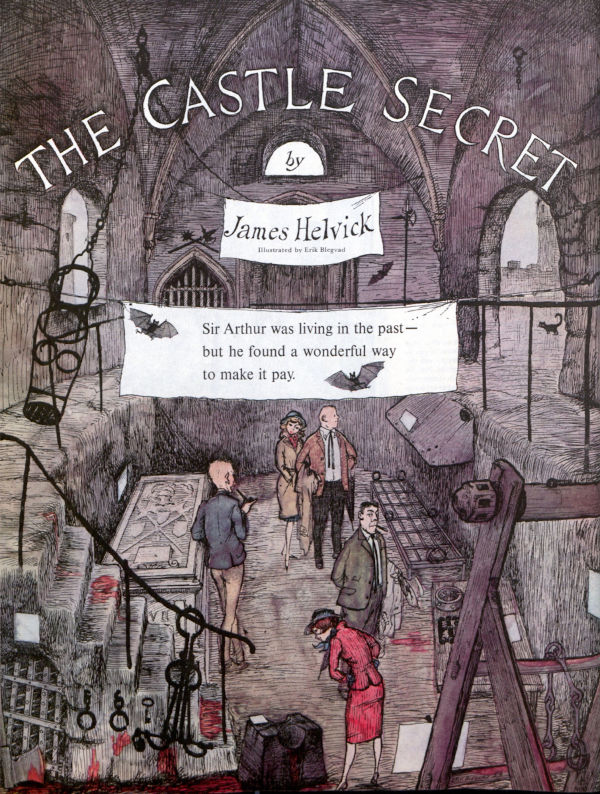

By way of a long winding staircase they descended to the dungeons. Here was black gloom, alleviated only by the faint light from slits high in the walls.

“Mind the rack, my poppet!” Sir Arthur cried in agitation as Nancy bumped against a dimly seen contrivance of poles, rollers and pulleys. “It’s good, but it’s flimsy. I knocked it together myself. And now that all those eager students of the medieval way of life have gone, we might have a little light on the scene.” He snapped a switch, flooding the large circular room with electric light. “When I opened for business,” he said, “believe it or not, this place was scarcely furnished. Not a rack, not a thumbscrew, not a garrote in the place. Terrible condition to leave a dungeon in.” While his visitors surveyed a satisfying array of instruments of torture, each with its notice luridly describing its uses, Sir Arthur approached what seemed to be a stone coffin set against one of the walls. Its top was roughly chiseled with some vaguely heraldic device and the notice beside it said: “Tomb of the first Sir Arthur Ludd circa 1300. Please do not touch.” Sir Arthur drew a key from his pocket, inserted it in a lock cunningly concealed in the heraldry, and threw back the lid.

“In addition to thumbscrews and such,” he said, “another thing I personally expect to find in a cellar is booze. Now what will you so to speak — ”

The supposed tomb of the first Sir Arthur was indeed well stocked both as to quantity and variety of liquor. “Porter, my dear boy,” said Sir Arthur to Jay, pouring whisky lavishly and setting the glasses on a table otherwise occupied only by a number of skulls, “just pull up a couple of coffins from the corner over there, will you, and we’ll make ourselves comfortable.”

Having drained his glass and refilled it, Sir Arthur patted Nancy cozily on the thigh and looked her over admiringly. “Lovely,” he said. “All such changes as can be observed are for the better. You don’t mind” — he turned to Francis — “my making passes at your wife? It isn’t as though I saw her every day.”

Francis also drained his glass and re-filled it. “It seems to me,” he said, his voice rising somewhat, “that you’ve been making passes at my wife for the past eighteen years or so. Furthermore, she has reciprocated your — so far as I am concerned — unwelcome advances. You and your high-mindedness! I could sue you for alienation of respect.”

“What the devil d’you mean?” boomed Sir Arthur, his nose deep in his glass. “Are you aspersing this woman? I could sue you for slander. We may be a second-rate power, but we’ve still got our lawyers.”

Nancy rose suddenly and stood over Sir Arthur, her foot tapping dangerously on the stone floor.

“You’re entertaining us very nicely, Arthur,” she said, “but what about your ideals and higher aspirations that you used to tell me about?”

“Yes, indeed,” interrupted Francesca. “Those ideals and standards of yours have been pushing me around for years.”

“And I, let me tell you,” said Jay Porter, also rising and standing over the baronet, “have suffered the indignity of being looked on as an unworthy squire of this beautiful and innocent girl because the Ludd yardstick says so. You’ve deliberately humiliated me.”

“But I mean as it were sort of,” said Sir Arthur, “I’m a perfectly ordinary sort of a chap.”

“That’s not the way we heard it,” said Francis.

“You wormed yourself into our home as a paragon,” said Francesca. “You caused friction and resentment.”

A mournful voice was heard calling from a long way off at the top of the stairs.

“Have you got the key of the blood cupboard there, Sir Arthur? Execution block needs a new coating. Lot of visitors today and you can’t stop some of them fingering the bloodstains.”

Sir Arthur got to his feet. “Excuse me,” he said. “There’s a special bloodstain I make up in the lab. They must put it on in the evening; otherwise it’s still sticky in the morning. Bit too realistic.”

The visitors stared at one another as the noise of his feet stumped away up the stairs.

“And that plausible rogue,” said Francis after a silence, “has been imposing on us all these years.”

“He’s a genuine scientist,” said Nancy.

“I don’t doubt it. The point is that as a high-minded arbiter of ethical and social behavior he has been an impostor all this time. I told you I wished you had never met him.”

“But I’m so glad I’ve met him again,” said Nancy. “Otherwise he’d have gone on and on forever being a cause of friction. As a common human being he’s harmless.”

“As a common human being,” said Francesca, “he’s sort of nice.”

“Maybe,” said Francis, “but as an ideal he was hell.”

“But he won’t be any more,” said Nancy. “As an ideal I’ve dropped him.”

Francis kissed her warmly.

“In that case, may I yet dare to hope?” said Jay Porter. He kissed Francesca lightly on the cheek.

Sir Arthur came stamping down the stairs. “Had to find the key for him,” he said. “People like blood. Have some more whisky. But wait a minute!” He had an air of sudden recollection.

“Weren’t we just having an awful row?”

“It’s over,” said Francis. “You’ve exploded and we like you better that way.” “Your presence in the flesh has brought happiness and harmony to all” said Jay. “Now that you’re a human being,” said Francesca, “I shall call you uncle.mI think I’ll kiss you.”

“Do that,” said Sir Arthur, “and then I’ll kiss your mother.”

“Meanwhile, I’ll have some more whisky,” said Francis.

“It’s good stuff,” said Sir Arthur. “Been maturing for an awful long time. The only genuine antique on the place.”

Featured image: The visitors surveyed the instruments of torture, each with a notice of luridly describing its uses. (Erik Blegvad, SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now