Even though Joseph Hergesheimer lost almost all of his notoriety by the time of his death in 1954, he was widely regarded as one of the most popular and important writers of the 1920s. Hergesheimer’s style was known as the “aesthetic” school at the time and he was often grouped together with James Branch Cabell and F. Scott Fitzgerald for their novels about America’s most wealthy. Hergesheimer’s fiction explored class struggle alongside beautifully crafted scenes of nature and the frontier. He published several short stories in the Post including “Early Americana” which follows the irritable experience of a Kentucky heir during his return home after years in the West.

Published August 27, 1921

Nothing broke in on the tranquil seclusion of the garden but the floating sunbeams and the songs of the mocking birds. The high formal privet hedge shut out the yellow sand-and- clay road and all that passed over it. It seemed to be a barrier for the impalpable as well as for the actual; within, the cross currents of troubled existence, the disturbing sense of illimitable space, space just then loud with calamity, had no being. The garden, a long rectangle against the wide white face of the house, was divided again into small rectangles and plots by paths and low square-cut hedges and borders. There were many flowers, flowers laid like bright old-fashioned ribbons or spread like shawls of lavender and rose and gold silks; the cool depth of the flagged porch was banked with them, blazing sheafs cut and placed in terra-cotta bowls, pots of growing flowers, clear blue and silver-white and crimson, so that the reflected light there was kaleidoscopic with splintering, swordlike colors. But the tone of the garden, the close, was predominantly green. Filtered through the green leaves, held by the hedges, low and high, the air assumed a transparent and leafy shade intensified by the dispersed amber sunlight. The mocking birds with their experimental liquid melodies were not now alone; for the brown thrushes had arrived and were singing; and others, gay, scarlet, in feather but songless, were flashing through the serenity so absolute that it might have been shut in glass.

Standing just off the porch, his shoes yellow with the dust of the road, Rudd Selborne listened subconsciously for some harsher reassuring sound, a satisfying noise, in reality; but none was audible. Then he wished that his father would appear so that they might finish as quickly as possible what must be a difficult, probably even an ill-tempered scene. This latter possibility Rudd, better realizing Charles Selborne, recalled; his father might with every reason be bitter; there would be no lack of force, of decision, in what he would say; but its expression would be even.

Rudd wondered with a sense of angry impotence at the tremendous, the ridiculous difference between his father and himself. It was blamed hard on both of them. At one time his oddness — the word was the family’s rather than his — was attributed to stubborn youth; but that wouldn’t do any longer, now that he had passed his twenty-sixth birthday. No, his vagrancy — another outside phrase; his Aunt Sana’s — could not be counted a mere dislike of school, of authority. There he paused, frowning. He was slender, well put together; but in appearance Rudd lost the advantage of that because of a pronounced stoop which gave him an air of listlessness, a lax indifference. And this was further marked by an expression of sleepiness that dwelt habitually in his lowered face and half-shut eyes. It was this, perhaps, which gave his rare quick upward glances their surprising blueness, the conveyed impression of an instant penetration, a disconcerting understanding. He threw his head up now, his mouth hard and eyes cold, and gazed over the clipped verdure, the planned vistas ending in white marbles and a fountain dripping with faint music into its carved basin. But whatever conclusion he might have reached was dissipated by the decided, unmistakable walk of his father across the flagging.

“Well, Rudd, so you are back,” he said at once, as directly as possible; and he extended a firm, beautifully kept hand. This left Rudd Selborne at a disadvantage; his father’s manner was like the insulation of a wire — it enclosed utterly what currents, what fire might be within. “You have been a long time away this trip; close on two years,” the elder continued, sitting in a woven-reed chair with glazed-chintz cushions. “Where were you?”

“Mostly in Oregon,” Rudd replied, still standing. Then adding the explanatory word “Apples,” he sat on the porch’s edge, his carelessly dressed figure conspicuous against the banked and gorgeous flowers. “I played around the Texas oil wells first, and got south as far as Aransas Pass, and then turned west. It’s curious,” he said reflectively, as though to himself; “I am always drifting to the West.”

A prolonged silence followed this, through which Charles Selborne’s hands were lightly folded on his immaculate striped-flannel knees. He had thick gray hair and a long tanned face across which his eyebrows and a brushed mustache lay in heavy parallel lines.

“I am wondering,” he finally spoke, “what exactly to say to you, how to begin; it is, at last, very important.”

Then, for the moment deserting that necessity, he told Rudd that his sister and her husband were there. Rudd nodded.

“What is he really like?” he asked.

“I like Saxby very well indeed,” the other replied; “I am very glad to have Greta married in England, and to him. It helps to close up the bonds between us. The whole connection is good, and, besides that, it is so pleasant and convenient to have Chinahouse and the other places to stay in. But this is far from our affair, yours and mine. We had better return to that before the others come back and interrupt us. What I want to be, since I’ve pretty much lost all my patience, is fair; fair but final. This over, I shall have little or nothing left to say on the subject, perhaps, in a certain case, to you.

“I’ve tried my damnedest, Rudd, but I can’t, I simply can’t understand you. If you were a fool or actually wild, that would be one thing. I could deal with that; it is not, unfortunately, unheard of in the family. But all that I can dimly make out, where you are concerned, is that you have a taste for common — yes, vulgar things. No, don’t interrupt me. Your chance to talk, to explain yourself, will come later. You must listen to me now. If, as I said, you were only stupid—” Charles Selborne’s voice bore a perceptible trace of regret that this comprehensible state were not true. “Yet at school all the masters agreed that you had a capital head — if and when you chose to use it. However, look back at your record there. Practically you finished, got hold of nothing; you were even — this seems strangest of all — indifferent to the games, to sport.”

“The games all struck me as being so set and silly,” Rudd put in.

While the Selbornes are one of the great sporting traditions of the country! However, we’ll let that go; I dare say it’s unimportant compared to the rest. This is what, principally, I am forced to say to you” — the clasped hands had an appearance of tightening, a higher color showed through the tan of Charles Selborne’s face — “the past, the present, cannot be the future. You must change! I am not threatening you, Rudd. I don’t believe in threats. I shan’t even speak of cutting you off. However you may feel, I have no taste to think of you as a pauper. Money, a great deal of money, will always be yours. But you can’t continue roving as you have in the past six or seven years. It is too humiliating for us here; you are becoming too cheap a figure. Exploration, yes; or game, big and small; rubber in South America; rubies in Burma. But just to wander in common capacities in the least interesting parts of the United States — no!

“What is it in you? Can you tell me? Can you explain yourself? For now is the moment. I have determined to come to an understanding with you. I won’t put up with this — never knowing where you are or what to say for you — any longer.

“Either you are a gentleman, a Selborne, or you are not. From now on I can see this much — you will be dignified or, where your world matters, damned.”

II

Rudd Selborne’s gaze remained fixed on his worn shoes, so sharply different from the russet and white buckskin of his father’s.

“What brought me here,” he explained, “was that I read in a paper of Aunt Sana’s death; you’d miss her, I knew.”

His father nodded. “It isn’t what brings you back that puzzles me, but what takes you away.”

Rudd’s glance was swift but not furtive. A frown gathered above his eyes, and in his difficulty he ran his fingers through his slightly curling light hair.

“I can tell you only in a roundabout way,” he proceeded, and then he made a gesture, at once repressed and violent, toward the garden. “It’s all so finished here,” he almost cried; “there isn’t a twig on the paths, not a piece of grass out of place. It doesn’t give you anything! The games at school — and the shooting you spoke of — they are the same. There isn’t any chance in them, they are all laid out, tied up in rules.

“And when you do make a goal or kill an animal, what is it, after all? You don’t really take a chance; you risk nothing. I didn’t, you’ll remember, like the war any better. I saw enough of it to know, and there was something the matter with it — the same emptiness, at bottom. It never seemed quite real to me.”

“There, at least, you are no more than idiotic.”

“I didn’t expect you’d agree with me; I was only trying to tell you. The life here with Greta and her husband and, in a way, you, while I can see that others might find it splendid, is like the garden — all hedges and clippers and regulations. I like to see things coming on, new things, or — real, like the pit of a steel mill, or hundreds of acres of young fruit. And I like to be with and talk to the people around them. Then there’s the West itself; that’s as strong as anything.”

He stopped with the baffled feeling of having explained nothing, made nothing clear.

“What I can’t overlook,” his father insisted, “is your indifference to responsibility, to name and power. You have the two latter, and the first should be inbred in you. There was never a time in the history of our country, of the world, when responsibility such as ours was more badly needed. Men of property, gentlemen, must show a solid strong front to the hysterical mass. We have to lead, not only by power but by example. That annoys me further; on your mother’s side, through Kentucky, and on mine, Rhode Island, you go back to the very beginnings of your land. You are as American in the best sense, at least by birth, as it is possible to be. Yet you act like any inconsequential immigrant. Haven’t you any sense of nationality, of duty? Hasn’t the dignity of a career, in the diplomatic service or even politics, occurred to you? Must you ignore every opportunity?”

“It sounds pretty bad, doesn’t it?” Rudd agreed. “And I can’t explain it any more without making it sound worse. But you might as well have it and get it out of the way. I haven’t the slightest feeling about diplomacy and those other things; and, while I realize I’m American enough, somehow I can’t connect that with what I run into here. I mean the Kentucky border. The idea of one seems to be so different from the idea of the other. It’s like paying to see Buffalo Bill and being taken into an English comedy, if you get what I mean.”

“It sounds to me,” Charles Selborne said, “as though you had no patriotism.”

“I haven’t,” Rudd quickly replied; “not any that you would recognize. If it weren’t for what I — I owe to you, I’d never come back into this again. I feel right now, talking to you, a sort of dislike for all the places and people here and at Newport or wherever they are. No, perhaps it isn’t that — they can do what they like so long as they don’t expect me to do it too.”

His voice grew rebellious, even sullen, and his head was bent so low that only the crown of his light hair was visible.

“You are rapidly destroying whatever opinion I once had of your intelligence,” the elder asserted crisply. “I am inclined to have less and less patience with you. When I began this talk it was with the idea that a great deal could still safely be left to you. I was wrong and see that it can’t. Well, here it is — you must stay with your family and traditions. I will not have you disappearing again and again, and after a year or more turning up in such ridiculous clothes. I don’t care what you do, so that it is recognizable — sail yachts, breed hunters, collect butterflies. But after this I am through with your tramping; it is, you know, precisely that — you are a tramp. A Selborne a tramp!”

Rudd rose, his expression still stubborn, noncommittal. “I’ll do what I can,” he said at last; “I won’t promise anything. It’s queer you won’t see that all I’m after is independence. That’s it, really; that’s it back of all the rest. I am not independent here, where everything is thought out for me. I have to do things whether I like them or not, feel like doing them or don’t. And you all have to do them in the same way too. Why, everybody even talks alike, the same slang in the same accent, and if you’re different you get the blank stare. As for the girls —”

He paused, and Charles Selborne shot from under his heavy eyebrows a swift speculative glance at his son.

“My own opinion is,” he declared, “that the girls are superior to the men. Certainly they seem to have more vitality and initiative. Several here this winter are very charming and easy to look at — Margrete Hastings particularly; and a great many admire Ann Waite, but I must say she is too erratic to charm me. The height of ambition for some of these young girls is to look as though they came from the exterior boulevards of Paris.”

Rudd Selborne was potently not interested in that; he had grown restless at so much talk; and at the sound of wheels on the drive he nodded, paused a moment, and then went into the house. A footman met him in the hall, prepared to show Rudd where his bag had been put; where, in his father’s house, he was to sleep. The room was extremely pleasant; the mahogany furniture, old and soft in color, took an added grace from the high white paneling against which it was set; long casement windows open to the garden, the fading sunlight and the mocking birds, admitted, as well, a warm and languorous and scented air. Some of his clothes, the servant informed him, had been brought down from the North; he would find them in the closet. When the door closed upon the man, in a canary-colored waistcoat, Rudd took off his coat, rolled up his sleeves and sat gazing moodily at his bag, a cheap affair of imitation leather, purchased in Portland.

Already, at home, if it could be called that, hardly more than an hour, he felt constricted, irritable. It was in the atmosphere about him — the quality against which instinctively he rebelled. Here he might just as well have been one of those cut flowers stuck into a pot on the porch. In a way his father was right; it was a damned shame that with so much ready to be enjoyed he couldn’t enjoy it. All that money! Perhaps because he had always taken money for granted he paid little attention to it; in his existence it had slight, if any, value. He didn’t require expensive things; cheap clothes, casual food, bare surroundings satisfied him as fully as the most elaborate. The truth was, he realized, that he never thought of them. His bag, for example, sodden and torn and smeared, its painted pretense dispelled, seemed just as good to him as pigskin heavy with straps and gilded catches. He was hungry, and the thought of waiting until half past eight for dinner, of changing for it, annoyed him excessively.

III

There were at dinner Charles Selborne — his wife had been dead for twelve years — Greta, his daughter, and her husband Saxby; another young Englishman named Powderson; a Miss Torrance, past middle age and ugly, but keenly alive, in contact with life; Margrete Hastings; Mrs. Badger Kane, who, although in chiffons, still contrived to look as though she were on the hunting field; and Rudd. He sat between Margrete, whom, by birth, he had known all his life and hardly seen, and Miss Torrance. The latter talked to him with her unremitting vigor, principally about her earlier exploits in driving; while Margrete said practically nothing. His father had been right, Rudd reflected; she was as pretty a girl as he recalled, with delicate rose cheeks, an arresting nose, and — as much as could be seen under broad bands of brocade — pale bright-gold hair. He made two efforts to talk to her, restricted by a total lack of any common interest; and while he was speaking she gazed with a smile directly into his face; but when he stopped all animation, attention faded from her face as though it had been wiped away with a sponge. Once she asked him for a cigarette, but when she saw the democratic half crushed paper pack he offered her she declined, and turned to Powderson, on her right. Rudd caught phrases of the Englishman’s conversation:

“Rather; splendid I call it here. . . . No, not long; fact I only came out December, and then left New York straight on to teach the boys at Mr. Blabon’s. Jolly little fellows they are, too; though I must say I don’t like their football as well as Rugger. . . . Illinois — what is that? Oh, I know! It’s a city. No; one of your states. But if it is east or west, north or south —”

“My dear,” Miss Torrance went on, “the two of us were left in the ring, Carrie and me. The judges couldn’t decide which of us was the better. Then they told us to get out of the traps and in again; and there is a way of holding the reins, of shifting them from one hand to the other. Carrie didn’t do it; and so, you see, I took first.”

Rudd nodded.

Margrete was saying to Powderson, “But it’s too utterly easy to toddle. I’ll show you.”

“It’s nice to see you, old infant,” Greta called across the table to Rudd. “I must say you’re looking fit enough. I told Ann Waite you were about to be here, and she asked a hundred questions. Your career — or, rather, the lack of it — interests her strangely. If you are not canny she will have it over you like a tent. These young things are horribly up and doing. Yes, Miss Torrance,” she replied to a question, “we were in Ireland all summer, hunting with a pack of otter hounds. There was an English pack over at the same time, and we were great rivals. We did them in, finally. It was ripping, splashing through the streams all day and staying at the little lost inns at night.”

“What is this Ann Waite like? I don’t seem to remember her.” Rudd made a third attempt with Margrete Hastings.

“You wouldn’t. She appeared from the nursery only the day before yesterday. About a scanty seventeen, as scanty as her skirts. But if you think she’s not a ball of fire — Hair banged of course; cigarettes naturally; I’m not sure but she has one of those little English brier pipes. Been in France a lot. Dresses like a ragpicker in the most expensive materials. Drives from the men’s tees. Father a total loss and mother now married to a mild Italian. Anything more?”

“No,” Rudd returned; “I’ve got her complete.

The dinner, he thought, dragged interminably; and he was relieved when the women left the table. Powderson moved to the chair by him.

“I’ve heard a good little bit about you,” he said in a friendly, interested manner; “you have been around. You were lucky, too, about the war; I had rotten eyes, and missed the best.”

“I wish I had,” Rudd replied, and then he flushed faintly at his father’s expression of annoyance. “What I meant was,” he addressed Powderson, once more wearily taking up his burden of explanation, “that I didn’t understand it; it was mostly, for me, in the dark. Some wars I’d give all that I was to be in, like the one Italy shot into Austria; almost any war to make you free.”

“Of course,” Powderson warmly agreed; “the English, you know, are the freest race on earth. We have always fought for freedom.”

“I suppose that’s where we got it,” Rudd went on, agreeably enough.

The butler was passing the liqueurs, white crème de menthe with a dash of brandy; a second man followed with the boxes of cigars, the silver tray of cigarettes and flickering spirit lamp. Powderson sat tranquilly at ease, his feet, in correct pumps, extended before him. He had an engaging highly colored face, rather small eyes and a readily smiling mouth. Rudd didn’t care what he had; he wasn’t interested in anything around him, and his habitual restlessness increased. He disliked nothing, he wanted to change nothing here; only he passionately wished for something far, far different for himself. What? A new land, a young land, space, activity, liberty — the West. He had been already, at twenty-six, where? What? A winter on a sugar estancia in the province of Camaguey; and in Florida — that he hadn’t liked, it was the South; in Northern Oregon; a summer in the wheat fields of Michigan; another summer helping to sail a pleasure boat at Mackinac Island; that time in the Texas oil regions; in a steel mill outside Harrisburg; the anthracite coal lands; on an asparagus farm in North Carolina.

He had worked hard, labored; he could work where his interest was held, while it persisted; but sooner or later, in one month or six, the irresistible desire to move on would overtake him and drive him forward. Suddenly he remembered with intense envy his Kentucky forebears; their life was his ideal. They weren’t simply idle explorers, hunters, sportsmen; they were conquering a continent, finding a land, a home of their own. They fought not silly games, killed not quail in the safety of game preserves, but went up against danger, against a wild that was in every sense a trackless wild. They, too, had turned away from the old, the settled, the bound; from butlers and Bohemian glass and rigorous customs. They wouldn’t be coerced; and taking with them only their courage and endurance, their indomitable blood, they had left the money, position, ineffectual honors behind.

The Rhode Island lot, as well — his father’s family — had been good birds, with troubles, Indians, of their own. Their rebellion and removal to the West had been largely a spiritual affair. They had been determined to think what they wanted to think, with no suggestions or prohibitions from anyone. Rudd studied his father curiously; erect, his gray hair exactly brushed, his pearls impressive in the fine linen of his dinner shirt. It was queer that all he had been recalling had resulted in just that. He was a very handsome, a very distinguished-looking man with qualities which he, Rudd, would never begin to possess. Well, he didn’t want them. He preferred his own.

“Perhaps we had better go in,” Charles Selborne proposed, and they rose and moved toward the drawing-room.

Powderson found Margrete Hastings at once, and with suppressed laughter they began to toddle in a corner, while she whistled. Miss Torrance was already seated at a bridge table, and a game formed without delay. “I’ll take an extra on Alicia Kane,” Saxby called back from the porch. “How much is it?”

Rudd walked past him into the garden. The night was profoundly dark and there was no sound but the drip of the fountain. For how long, he wondered, could he stand this? If he went away again, his father had said, it must be, where the bonds of birth were concerned, final. What ought he to do? It might be that love, if it could be managed — marriage — would kill his deep restlessness.

IV

But if any connection had formed subconsciously between that idea and the thought, for example, of Ann Waite, it was dispelled at once when Rudd saw her on the first tee of the Camelata Golf Club. She was too absurdly juvenile, and too thin. That was his immediate impression. There was a tournament for men and women in progress, and the tee, the benches on the left, the rustic chairs under the pines, were filled. The women, in silk or knitted fabrics of the utmost simplicity, gray and green and soft browns, with their faces muffled, hidden to the eyes in swathing veils, were striking against the smooth course cut through the blue haze of the evergreens; and their dogmatic voices, the terms of a sport, vigorous trivialities contrasted with and made incongruous the appearance of the veiled East.

However, there was little withheld by the garb of the girl gazing with a mocking, shifting light into his face. He had said, with an indifference but poorly concealed, that he hadn’t met her before; and she had — in a voice as glancing and unsettled as her eyes — blamed heaven. Imperceptibly his conception of her juvenility decreased; yet no liking for her made a corresponding gain.

She tentatively mentioned golf. He had played, well enough; he didn’t like it.

Had he been here before? No.

His father’s place, Banksia, was very beautiful. Well enough, he repeated his phrase.

“I don’t believe you like it — any of it, or any of us,” Ann Waite declared.

“Well enough,” he said for the third time.

“That isn’t even a polite lie,” she replied. “Since you don’t — why not?”

He couldn’t go into that again, he reflected; he was absolutely worn with explaining his peculiar attitude toward this life. She reminded him that it was his world; and that, she concluded, gave him the right to regard and criticize it as he chose.

“I think I’ll take you buggy riding,” she asserted after a pause. “You can’t object to that. This, you know, is a very early spring; all the flowers in the woods are out together, the jasmine and dogwood and azaleas. I’ll come for you about four this afternoon. I promised to play some round-robin tennis; but I won’t; I want to explore you.”

“I suppose it will be no use to say that I hate ambling through a patch of trees?”

“None,” she told him firmly. “I saw Margrete and she made me frightfully curious about you. There was something, she said, she didn’t know what. I doubted it at first; but I see there is; and I must find it out.”

“Don’t be silly!” He turned away as soon as possible, rather annoyed than not.

He saw her a little later, driving; and the sudden force, the whole sweeping vigor of her body surprised him. She wasn’t thin exactly, he corrected this hasty impression, but slender. But what difference did all that make to him? Her hands, however, driving a bright bay mare with a banged tail and a vicious disposition, moved him to an acknowledgment if not precisely admiration. She did things — slight, unimportant things — quite well. The road was no more than a sand track dipping and turning through a woods, more than a patch, bright with gay screens and planes of blossoms. The truth was that he felt fairly contented. The mare became more reasonable, settled into a short steady trot, and Ann Waite and he lounged in the buggy.

“The life here is rather pallid,” she admitted.

“What did you expect?”

“I thought perhaps you might tell me. But of course what we all want is a thrill. Yet it’s no better at Palm Beach; you just work harder there, that’s all. The result —” She made a disdainful gesture. “We’ve tried good thrills and bad thrills, and none of them have a bit of kick. Did Margrete tell you that I was seven or seventeen? Anyhow, I’m not too old, there is a long hole before me, but I can’t think of anything new or exciting to come. I’ve been considering love as a possibility.”

“So have I,” he admitted.

“It seems to me a lot like swimming,” she went on; “it’s no good if the pool’s too small, you just get muddy. Deep and wide is the idea.” She gazed at him with a fresh speculative interest.

“You’ll get nowhere if you’re considering me,” he informed her. “I wouldn’t love you on a bet; it would be too damned uncomfortable.”

“We might both do worse,” she asserted calmly; “we’re not fussers. And when the novelty wore off, when the thrill was gone, I’d kill myself. I shouldn’t stay around like a painted ship on a painted ocean.”

“Not a chance,” he repeated vigorously. “That isn’t my idea of marriage at all. You’d be like a mosquito; and I want peace.”

“You’re rather hellish complimentary,” she observed. “But it is the fetching way to be with me. I’ve seen a lot of older men in my short term, and I’m sick of their line. Take a ride with me, little girl; see the nice box of candy — that and the freshness of my charm.”

“The charm of your freshness,” he suggested.

“Do you like me any better?” she asked.

“I don’t like you at all,” he explained; “but you are real enough, now; you are yourself, if you see what I mean.” They were returning, and he considered her with one of his penetrating lifted glances. “You are no good for me, because you are so dissatisfied; we’d pull down the house in a week. You’re sick with it, that’s the trouble. So am I, but I am going to end mine; I’m going to find something.”

“What?” She caught his wrist in her hard narrow grip, a figure of passionate questioning.

“Oh, I don’t exactly know.” Instinctively he retreated. “Setting up fence posts, perhaps; clearing land; something far away and — and new.”

She relaxed, with an aspect of disappointment that approached weariness.

“That hasn’t a gleam for me; I hate the honest and the rugged. I never want to go to bed nor get up. Let the maid, the butler, the chauffeur do it! I am rather exhausted with you, myself. Are you going to the Allertons’ fancy-dress show tonight? How about overalls and a halo?”

“I’d put off thinking of it.”

“Probably it will catch you.”

They turned in at the circling drive of Banksia, passed the transparently green thicket of bamboo; and the buggy boy, riding behind, his legs over the back, hurried around to hold the mare.

“I don’t know what to wear,” she proceeded, gathering up the reins with a smartly slanted whip. “My legs are thin enough for a fly, but I haven’t enough of them.”

Rudd nodded as she drove away.

In his room he flung himself out on the day bed under the windows. It was rather a shame about Ann Waite; there was, as she had suggested, nothing ahead of her. She was better looking than he had realized; not at all bad, in fact; and full of an unexpected warm force. In retrospect she troubled him, persisted in his thoughts. The freshness of her — but he had put it the other way about! He had decided against the Allertons’ party, but now indecision seized upon him; the nights here, where he had slept badly, were so long. The music would be good, and he could stay out on the porches, leave when he wanted. Ann Waite was unhappy; she might not know, acknowledge it, but she was. The thing was — could she make any other grade? Probably not. There was her father, who had been a total loss. It was, though, he decided, a degree of superiority, of mind, which here made all the trouble for her. It was like being shut in a part of the zoo with animals different from yourself; not better nor worse, but different. With her it wasn’t quite so strong; she was more like these than dissimilar. As for himself, he didn’t, in spite of so much, see how he could stay in the pen, refrain from jumping the fence.

V

Driving through the night over a soundless road toward the Allertons’, Rudd was still engaged in the troubled examination of his affairs. He didn’t, he told himself, want to be a fool, throw away for nothing — or at least for what was without reason — what were universally acknowledged to be the world’s greatest advantages, money — not just a competency, but one of the country’s fortunes — and place. Maybe, as his father had almost asserted, he, Rudd Selborne, was no good, a drifter; yes, a tramp. Perhaps the truth about him, about his careless person, was that he was naturally slack. Other boys at school had turned out to be worthless, without sand or purpose; he knew men, who belonged principally back in pre-prohibition days, who were no more than charges on the resources and patience of their families. Undoubtedly, being a Selborne, a decent Selborne, in addition to its advantage, required a serious effort and ability. A great many people were silly withmoney; it was a power, he could be a power. It was, for example, very pleasant driving easily through the soft darkness, the lantern swinging on the bottom of the buggy casting a warm blurred light over the sandy way. The night, as well, was warm, relaxing, restful and a little strange, unnatural, simultaneous with the bitterness of the winter north. What at the moment he wanted, he insisted, was not the thing to consider now; he must intelligently face the future.

He reached the wide lighted drive of the Allertons’ without equally arriving at any decision: there were still unresolved, on one hand what, Rudd felt, he should make a determined effort to become, and on the other all that he instinctively was, mysterious and illogical and compelling. A group of older men were sitting outside, their white linen oddly evident in the gloom; but the music and dancing had begun within. Rudd stopped to speak to Richard Allerton, and, past the door, to his wife, a small rotund woman with an infectiously cheerful voice and manner.

He saw Ann Waite at once, sitting on the steps directly across from him. She made a gesture of recognition, and because it was the obvious, the unavoidable thing to do, Rudd moved over and sat beside her.

She was wearing a short vivid-orange skirt with a broad informally tied black sash with long ends — her hair was completely hidden by a black band — and a waist which looked as though it should be cambric.

“I’m the girl at the candy wheel in a fair,” she informed him. “No one has guessed it yet. Can you dance — I mean, worth speaking of?”

He rose indifferently, and without further speech they swept out into a series of slow intricate steps.

“You can,” she admitted; “your heel stuff is specially praiseworthy. But I don’t like dancing with you, I have a feeling that you are dead on your feet. Let’s sit again; that’s more better. Do you really dislike me as much as you make painfully evident?”

“Why, no,” he replied; “I don’t dislike you particularly. It’s only that all this isn’t my lay. I am trying to come around to it though.” “And to me?” she interrupted.

“I suppose one might mean the other. If not you yourself, then someone more or less like you. But I’m not at all sure I can get it done; I may fail on the whole works.”

“Don’t hurt yourself,” she retorted. “It won’t really ruin my career if you fail. I am nice to you because you are so contradictory and different from, well — Freddy Lennard.”

She paused, and they watched Lennard pass, dancing, a slender youth with black smooth hair and a highly colored handsome face. There, Rudd thought, was the sort of son his father should have had; Freddy Lennard would have nicely decorated the Selborne fortune. All his expressions, his gestures, and especially his clothes, were smoothly correct; a mind, Rudd decided, like cream cheese. The floor was filling, the men had come in from the porch and bridge had started in the rooms at either end of the hall; the costumes were simple and bright. Powderson, in the striped denim of a farmer, was toddling in the enthusiasm of a new discovery.

Ann Waite was prettier than Rudd had thought; no, not prettier, but more — more engaging. Sitting on the step her shoulder touched his, and his pulse was not entirely steady. She was uncomfortably provocative; the charm of perversity. He might, it seemed, and without any tremendous effort, become very much interested in her. This, as his father had indicated, could end the problem of his restlessness. Rudd considered the problem of the girl beside him; he might let himself go, arbitrarily throw himself into the depths, or shallows, of all that she represented. Such a period of total surrender might reconcile him, turn him, contented, into a polo player or a diplomat.

She rose and with the explanation that she needed air preceded him out upon the porch; it was, but for them, empty, closely screened in wistaria vines, and pervaded by an unfamiliar and very sweet scent. They found a Gloucester hammock, into the corner of which Ann sank.

Rudd Selborne became promptly reabsorbed in speculation, the turning over and over of his difficulties.

“I don’t mind your not talking much,” she said at last. He never talked much, he replied; at which she pointed out her meaning. Probably Freddy Lennard would gladly gabble to her! She didn’t want Lennard, he made her faintly ill.

“I’ve lost a slipper,” she informed him, and put out a slim black foot. “Now the other one. Look, the first is off again; they are too big.”

“They will have to stay off,” he said decidedly.

The glow of a cigarette illuminated the malicious vermilion of her mouth. “Will you go buggy riding tomorrow afternoon?” she asked.

“If your shoes fit and I remember.” She leaned forward swiftly and caught his hand. “I’ll make you remember it.” Her teeth sank with a sickening sharpness into his palm, almost, he thought, to the bone. The pain shot up to his elbow and he was conscious of spreading blood. A hot rage at her swept over Rudd, a violent stinging brutality of feeling. He caught her roughly and, instinctively finding her mouth in the dark, kissed her again and again.

He released her as suddenly, with a giddy passionate resentment. In the silence he could hear the unsteady gasps of her breathing. How he hated her and himself — the whole world about him! Waves of sickness passed over him; curiously the pain in his hand and the music within mingled and became one twisted unbearable sensation.

“I am glad you did,” Ann half whispered; “I wish it had killed me. It very nearly —”

“It doesn’t matter what you are,” he broke in roughly, out of the torment of his being. “You can be as rotten glad as you please. Maybe I’ll be, too; after a while, when I don’t matter.”

The music for the dancing abruptly stopped; there was a pause, a silence, charged with expectation; and then a man’s deep stirring voice began singing:

Way up yonder in the frozen North, In the land of the Eskimos. I went there in the Sarah Jane, And I don’t care if I never get home again —

A wave of emotion, of choked longing swept over Rudd Selborne, so profound, so racking that he collapsed on the edge of the hammock. All his inmost being, his innate promptings, his fundamental dissatisfaction, flared into an overwhelming nostalgia for that other land, his land and his life. The voice rang beautifully, pitilessly into the still warm night, the spirit of masculinity and adventure and new places; it recreated the youth of a country, undrained men, virginal spaciousness; in the illusion of its music all was yet to be experienced, to be dared, accomplished; in it was life and sharp death and splendid uncounted folly.

Ann Waite’s slender tense arm crept around his neck.

“I was detestable.”

He looked toward her blindly. “I can’t!” he cried desperately. “Don’t let me!”

“Fantastic as it sounds, I understand,” she told him. “Perhaps, together, we might have. But I see it’s impossible. I suppose I’m gone already, and you’re very near slipping.”

VI

The hurt to his hand was rather worse the following day; the pain persisted into the next and the next, and Rudd was conscious that he should have it attended. He neglected this, however, principally because of the awkwardness of accounting for the evident character of his injury. He kept a handkerchief about his palm and avoided a direct reply to any inquiry. This was comparatively easy, since, as far as possible, he avoided contact with the people about him. An early breakfast, his buggy and the wooded drives and flat gray countryside, now irradiated with the tender green, the coral peach blossoms of spring, made this avoidance easy. A period of sullenness, a blank ill humor, had taken the place of his questioning, his effort to be approximately a Selborne. He attempted no planning, gave the future, near or remote, no consideration, but existed with scarcely an upward glance at the world.

The pain continued steadily, fretfully; and slowly he was brought to the realization that something must be done about it. He was walking through an unfamiliar part of the town, far different from the elaborate gardens and colonnaded white houses of the winter colony. The street was wide, it could hardly be identified as a street; there were oaks growing where they willed, sandy tracks by either uncurbed sidewalk, unkept plots of melancholy-looking grass, and minor ways that led with the utmost informality in and out. The houses were small frame dwellings, from which, oftener than not, the paint had bubbled and stripped and gone; about them in contracted areas spread bare gray sand.

One attracted Rudd by reason of a glossy magnolia tree, a dark-green tree and a bush of camellia japonicas with some belated blooms; and then he saw, nailed to one of the unsteady supports of the portico, a sign — Dr. Bolivar Coss. The name was so faded that it was almost undecipherable; the sign had an unsubstantial appearance. But — there was a sharp burning in his hand — it was so far away from all he knew that, following a sudden impulse, he went in and knocked on a door that held no other provision for attracting attention.

After a little there was a sound of footfalls within, an approach deliberate yet not stiff, and the door opened upon a girl who seemed to fill the entire frame. This, he then saw, was not quite true; she gave an impression of being larger than actually she was. This, though, was considerable — a solid young creature, taller, broader than himself, with untroubled brown eyes, a frank mouth, and a simplicity of garb adorned only by a red ribbon, not wholly fresh, in her hair.

“If he’s in I’d like to see the doctor,” Rudd Selborne explained. At the expression of surprise, the amazement that slowly possessed her countenance, almost becoming a panic, he grew impatient. “The doctor!” he repeated shortly, half advancing — as though, incapable of understanding even the simplest speech, she might respond to signs — his hand.

But in place of answering him she went forward to where she could read the name nailed to the post. When she turned to Rudd her expression, as though she had been darkened by an emotion, was altogether inexplicable.

“We never took it down,” she said in a wondering voice. “My father is dead.”

This unexpected and difficult development left him staring at her with nothing conceivable to say. He wanted to turn away, leave at once; but that he was unable so abruptly to do.

“I am sorry,” he told her with sufficient banality.

“But it was three years ago,” she went on. “I can’t imagine —”

She stopped, but her eyes continued to meet his; her natural mouth was slightly open.

“Perhaps it had better come down,” he suggested.

She nodded, and with a light pull he had the small board in his hands. Then he didn’t know what to do with it; he couldn’t quite hand it to her, nor drop it. Rudd set it inside the door.

“There is no doctor near here,” she told him; “and you have hurt your hand.”

“It’s nothing immediate,” he assured her; “I have been three days getting around to one.”

Without thought he produced a cigarette, but then paused, made a movement to retreat. But still her gaze held him. He struck a match.

“Wasn’t that awful about the sign?” she added conversationally. “But everything’s like that down here.”

“Aren’t you a South American? “he asked, and then had to explain that that was merely a humorous designation which had started during his military schooling at Camp Hancock.

“I was born here,” she replied, “and so was my mother, but father came from the North. He had to on account of his health. But he didn’t find much of anything but troubles and children. There are eight of us, all girls,” she smiled at him faintly. “Most are working now, and three are away; but it was right hard when we were young.” He had suddenly an impulse to linger and hear the placid unimportant details of her family and its life. Her voice was deliberate, restful and pleasant; her very bigness was soothing after — after Ann Waite; and, smoking, he sat on the edge of the portico. “I’m home just now,” she informed him; “mother’s been miserable and there had to be somebody to do for her. Emmy, she’s the youngest, thinks more about the boys than she does the bacon.” His companion, without self-consciousness, took a place beside him.

It was past noon and a slumberous veil of yellow sunlight was spread before them. The air was so still that the smoke of his cigarette climbed in a single column. Rudd had no impulse to talk; a mental relaxation had settled over him. He lazily noted features of the girl beside him. Her shoulders, under a cheap figured cotton, were strong, full rather than delicate; her whole body was big, big but not — or, at least, yet — fat. Her size, he discovered, contributed to her aspect of simplicity; that and the firm outline of the uncomplicated dress. She, too, fell silent; and Rudd became aware of her deep, slow breathing. There was something cowlike about her, he thought, with no uncomplimentary intent. The truth was that he found exactly that agreeable. Already he had a sense of familiarity, ease, there with her. There was no need to talk, to explain, to defend, to himself and others, his feelings.

“Do you live here?” she asked.

“I’m staying, I don’t know for how long.”

“Where?” “Out toward the Camelata Club.”

“Oh, I see; working for one of the gentlemen.”

His careless garb, he realized, the dust on his shoes — he had been walking — had deceived her. This inexplicably pleased him, and Rudd was careful to keep up the illusion.

“Not exactly that; I am just there for a while, at the Selbornes’. I don’t like it much, though; I am very different from all that. I don’t like it.”

“I reckon you would if you had a chance — I mean, to be really in it. They are as rich as rich. Mr. Selborne’s a handsome old man, so distinguished-looking. I knew a boy who worked in their garden. Mr. Thompson’s the head gardener. He’s Scotch and very religious, and goes to our church, Presbyterian. Might you be with him?”

“No; I’m in the house. But I don’t think I’d like it even if I were, as you suggested, a part. I don’t believe I could be a part.”

“Certainly you couldn’t,” she echoed him, laughing. “There’s no good thinking of it. You have to be everything in the world only to have them look at you. Why, the Selbornes carried twelve servants down here, and they have a house outside New York and a house at Newport, all bigger than the place here, Banksia.”

“You seem to know a lot about them,” he commented.

“How could you miss it?” she asked. “With what’s in the papers.”

A thin, ragged voice called, “Reba!”

She rose. “There’s mother. I forgot all about fetching up her tray.”

Standing in the walk, studying her briefly, he said, “I’ve enjoyed talking to you, and I think my hand is better. I’ll come by again if you don’t mind; perhaps in the evening.”

“That doesn’t mean a thing in the world down here,” she reminded him; “it lasts near all day. Supper’s cleared away at six.”

VII

Rudd Selbourne gazed with a new and personal interest at the back of Mr. Thompson disappearing through a pleached alley at Banksia. Now that he had been informed of the Scotch Presbyterianism, Rudd could trace it in the sanguine nape of the neck and a certain excessive caution in the bearing of the shoulders. It was nearly six. Tea and bridge were in progress on the porch; Reba Coss would now be practically done with the supper dishes. The Coss house was an appreciable distance away, and he debated driving there. This, however, he decided against, for he didn’t care to explain Reba’s mistake to his buggy boy, who otherwise was practically certain to let everyone in the neighborhood know that he, too, was a Selborne; and he was determined for the present that she should continue in ignorance of his identity. His reason for this was that things were so comfortable, so easy, as they were.

When he reached the Coss house he thought Reba was sitting on the portico, but when he drew nearer he saw that it was a younger but no less imposingly constructed girl. Her welcoming smile faded after a swift comprehensive survey of his unimpressive dress.

“I’m Amanda,” she told him indifferently. “Reba’s inside; I reckon she’ll be out in a minute.”

He took a place beside her, careless of her opinion, steeped immediately in the contentment he had felt here before. There was no need for Reba to hurry; it was soothing simply to know that she was placidly, sensibly near.

“I hear you’re at the Selborne place,” Amanda turned to him. “Tell me about the daughter, the one who married an Englishman. I’ll bet she never gets up till all hours. I’ve seen her and she’s not pretty, but that doesn’t matter when you have so many clothes. She looks nice in that blue homespun cape she wears. I’d certainly love to see her all set for the evening. Didn’t she win a big bet running around the Camelata golf course?”

“I believe she did,” he replied, reflecting on what a silly business that had been. “You see, they are awfully hard up for things to do.”

Amanda glanced at him with an expression of scorn.

“You must be one of those socialists; nothing suits you. Why, they’re busy all day and most of the night. I wish I had nothing to do like that; it’s not my idea of a hard life.”

Rudd gazed at her more carefully; she was superficially like Reba, but her eyes were sullen; her mouth — painted, he saw, badly — was at once hardened and relaxed. Her clothes had a faintly familiar air; they caught at an accent, a hint of color, a suggestion of line, of what was worn at the club. Even her voice, he recognized now, attempted the accent of Greta’s circle. It was too bad, for such models would hurt her seriously; in the end, if she went deeper, destroy her. She hadn’t the cool philosophy, the preserving cynicism, the endless money of, for example, Ann Waite. Amanda was Reba’s sister, and he was pondering the wisdom of attempted advice, when the older girl appeared. She was calmly glad to see him, and sat on his other side. Amanda leaned over and captured his cigarette.

“Just a drag,” she explained.

Reba regarded her with a mild censure.

“I don’t see why you bother,” she proclaimed. “It’s just another nuisance. Then people tell mother about it and worry her.”

“You make me sick!” Amanda retorted, rising, flushed and angry. “You all do. Why, there is no get-up or style to you. For all the difference it is to you a person might work in a cotton mill forever, and never have a scrap of fun. I can learn you this, though, and I don’t care who tells it on me — I’m not going to stick around here till kingdom come. Not by a — a hell of a sight.”

Unmoved, Reba told her not to be cursing and swearing. Amanda deserted the porch abruptly with a sharp swing of her meager skirt. The golden light faded from the melancholy width of the street; a mocking bird, close beside them, tried over and over a run of piercing sweetness; the shadows merged and accentuated the pervading grayness.

“I’m glad I met you,” Rudd told Reba Coss.

“You’re a right nice boy,” she assured him.

She moved nearer and their hands fell together. The peace in his spirit increased until it was no longer a passive but an absolute quality; he was conscious of it flooding, quieting every particle of his being. In precisely the same situation the following dusk, seated close beside her, holding her hand, he leaned over and kissed her. Reba accepted this without disturbance; she showed little emotion — except, perhaps, contentment — of any kind. The kiss tranquilized him; it, too, flowed assuagingly into his heart. Everything about Reba Coss satisfied him, particularly her bigness, her fine, slow vigor. She reminded him remotely of the earth itself, of the spring in the West.

He had, for his age, and the briefness of his knowledge of her, a surprising thought; she would, he told himself, be the splendid mother of many children; Rudd saw them clinging to her heroic knees, lying against her deep breast. And this vision filled him with a flooding sense of power, of fulfillment. It seemed to him that he was a part of the vision. Rudd kissed her again.

“The first time,” he explained, “it just happened. Now it’s different — I mean it.”

But before he was further committed he forced himself to leave, to return to Banksia. He had been at the point of asking Reba to marry him, and there was very little doubt but that he would return to the Coss dwelling for that purpose.

Still, it needed careful thought, but not on account of his father. The elder could, he would have to, get over such a marriage. Reba had good blood in her, that was evident; for though her dress, her speech were often careless, they were kept from the impossible by a noticeable, instinctive if unencouraged taste. With money a great deal could always be done for a girl. He already heard, in prospect, his sister Greta explaining Reba in New York, in Newport.

“The daughter of a Northern physician who was in Magnolia for the climate; yes — lungs. She hasn’t inherited that, at any rate; really a superb big creature. We are all devoted to her.”

To what might in Reba’s connection happen to her family Rudd was totally indifferent; he had no inclination to assume responsibility for Amanda, the fretful voice of the unseen mother; the other sisters he had seen but vaguely. He knew instinctively that if Reba loved him she would go with him and leave the past; and how eagerly under the circumstances the past would surrender her for the material benefit bound to reach them all.

Another complication lay in his marked disinclination to tell Reba who he was; there was no reason he could grasp for this unwillingness; she naturally would welcome the knowledge, at once forgive his deception. He had even borrowed the name of one of the footmen! Well, he’d have to get around to it.

But the next time he saw her he put it off. She had on a fresh light-blue dress, and without Lewis they went driving in his buggy. It was Sunday, late in the day; the six-o’clock dishes had been cleared away, and the wood drive, Rudd knew, would be empty of his connections. At that hour they would be playing bridge on the secluded porches.

He did something else, however; unavoidably in the flowery and scented dusk he asked Reba if she’d marry him. She didn’t answer for a while, but sat gazing into the far side of the woods.

“You’ll be perfectly safe with me,” he assured her; “I can take care of you, you see.”

She turned to him quietly. “I could take care of myself.”

“Will you marry me?” he repeated with a conscious formality, aware, as she couldn’t be, of the surface importance of his proposal.

Now he ought to tell her everything, but he didn’t; his reluctance restrained him unreasonably. Her answer was suddenly conveyed in a surrendering droop against him, a firm and not light sweetness. His arms around her, he had the sensation of actually embracing the earth and its fruitfulness; he was, it seemed, drawn into the very flowering trees, the vast green plains of wheat, the depths of profound lakes and high serenity of mountains.

VIII

Before him there was the double complication of explaining the Selbornes to Reba and Reba to the Selbornes. He didn’t specially shrink from the latter, either; his father, he felt sure, would welcome a Coss in place of the old indeterminate wandering. But the opportunities for his revelations were delayed by trivial and stubborn circumstances. Rudd wasn’t, taking everything into consideration, as happy as he told himself he should be; his love for Reba was so inevitable that he neither wondered nor questioned it. Reba had merged into his being so completely that he had no consciousness of a time before she was there. Yet — and this began to trouble him deeply — his restlessness remained; the magic of the West had not been slain. It was less rooted. in dissatisfaction, the contending elements in him seemed to have been calmed; but the steady compelling magnetism of new lands remained. It must, however, he assured himself, diminish before the overwhelming fact of his love, his responsibility to Reba. His love more and more rapidly would supplant every other interest.

Although no formal announcement of their intentions had been made to the Coss household he was accepted as Reba’s acknowledged suitor. The other sisters emerged into his recognition; Mrs. Coss occupied the portico with them through part of an evening. She was, strangely enough in view of her daughters, small, with dark cuplike depressions at the temples. Always she wore a knitted wool jacket of gray with a pink shell edge and pink ribbons. Over this her faded hair strayed in unmanageable wisps, while her feet seemed equally at the point of leaving the black felt slippers into which they were thrust. She didn’t in the least disturb Rudd Selborne; the truth was that even before him, so notably connected with the girl he planned to marry, she prompted scarcely a thought. Her clothes, her appearance, were what might be expected; naturally she wouldn’t be dressed by Greta’s people in Paris.

There was an informality in the whole Coss attitude toward him and life that pleased Rudd — an undisturbed simplification of existence. Even Amanda could put into a phrase or two her entire philosophy and desire. There was no such necessity in Reba; she lived rather than thought. She was, he told himself again and again, perfection. He talked about generalities still, and she listened with a calm inexhaustible patience and interest. Yes, she was the earth binding him, holding him steady, making possible the reach toward the sky. They were one in purpose and dignity and promised fulfillment. This simplicity, however, he reminded himself, couldn’t continue; it was made difficult by the fact that there was no reason for his suppression; the longer he put off his pleasant acknowledgment the more pointless his conduct appeared.

And on the afternoon of a sun-flooded Sunday — the end of June in earliest April — he prepared to end her ignorance. They were driving again over the road which, passing through the Northern colony, by the Camelata Club, led to the woods beyond. And Reba had spoken of his extravagance.

“The buggy really didn’t cost me anything,” he explained; “they let me have it at Banksia.”

Here, he decided, was the moment for his beginning, but they were upon the golf course, following, for its length, the fairway to the third green, and the brilliant presence and clear insistent voices of a small group at the tee made him again delay.

The women, masked in veils, he was unable to identify; in their gay attire, their jackets of thick silks, they were, he thought, like tropical parrots; and the men were almost equally without identifying features. A tall, graceful woman hidden in black prepared to drive. Beyond them Reba fell suddenly silent, she gazed ahead with her under lip lightly held in her teeth.

“It would have been nice,” she said, “if you’d been rich.”

He turned to her with an unaccountable disturbance.

“Why?”

“Those people back there — the clothes and the good time and all that.”

“Probably they don’t have half the time you do,” he replied sharply. “If you had a lot of money, like them, what would you do with it and with yourself?”

“I’d see that my face didn’t get burned as brown as a biscuit, that’s sure.”

His uneasiness was now justified to such an extent that he drew a long, painful breath. He had thought, apparently, of everything but the effect of the Selborne fortune on Reba. Money had no great interest, power, for him; but others, even Reba, were different. Why, the brown of her face was one of the things he particularly admired. Rudd loved her, wanted her as she was. But that, he saw now with an unspared clarity, would be impossible.

At this realization his uneasiness, his rebellion against all that was settled, fixed, tyrannical with custom, returned more bitter than ever before. It appeared to him that he was penned in a garden by tall hedges of iron fashioned like green leaves, among caged birds and pruned plants. But, principally, what a blind fool he had been about Reba; why, the entire world he was about to take her into would fight, scheme against all in her that he had sought, that he needed, that he overwhelmingly admired and loved. This he had already — in calculating the final satisfaction of his family — stupidly reviewed. If that happened he — yes, and Reba — would lose everything. He recalled Amanda. He was so agitated that he brought the whip sharply across his mare’s flank, and they bolted with a rocking speed into the soft, deeply rutted drive bearing to the right through the woods.

Reba sighed softly, and then, evidently putting her conception of the impossible from her mind, she settled contentedly against his shoulder. The anticipated happiness in the afternoon, in the surprise he had had for her, deserted Rudd. He was, he felt, faced with an immense difficulty, danger; the climax of his life was already, so early, before him.

No situation in the future could be so laden with irrevocable consequences. It was, he thought, a climax, but it was one without a perceptible issue. He was squarely caught. The mere fact of his desire, of being himself, was making impossible what, above everything, he needed.

A vision of the West, the rippling green, the wide frozen purity of Northern winters possessed him; he breathed in imagination the spacious air, the air so different from this; he was thrilled by the thought of turned virgin soil, the vitality of new towns, towns on limitless plains or by rushing narrow rivers, under the canopy of a primitive forest. The spirit of colonies and colonizing men; of big, tranquil, strong women, maternal women, filled him.

“Reba,” he exclaimed suddenly in an eager resonant voice. “What about our wedding? You don’t want the bother and expense of any formality, do you? I can guess how your mother feels about it, with money so scarce and all those girls around the house. And you know me — how I hate anything like that. Well, let’s get married tomorrow morning — you can tell them afterwards if you like — and go away. There’s nothing here for us; no money or place to be got. I’ve been to a part of Minnesota where they want men and women like us; it’s rough, or it will be at first; and you may find it lonely, unless I’m a lot to you, but there’s an opportunity. I — I have enough money to get us there and a little, a very little over; but we won’t need money, and I can soon make enough to keep you safe. Do you really love me, Reba? Will you go away from all you are familiar with, to a hard life with me?”

She sighed again, and her hand went across her eyes. Then she smiled at him placidly.

“That will be best, with things as they are,” she told him. “It doesn’t do to want for too much. But I reckon we’d better turn back so’s I can get my dress mended a little, and pressed.”

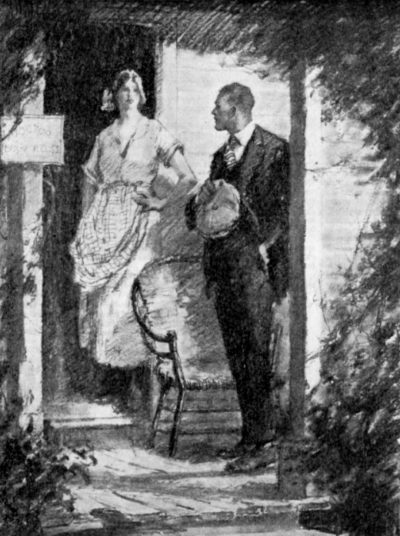

Featured image: How he hated her and himself; curiously the pain in his hand and the music within mingled and became one twisted, unbearable sensation. (Illustrated by George E. Wolfe)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now