Though scarcely studied or read by present-day literati, Booth Tarkington’s novels, short stories, and plays were wildly successful during his lifetime — from the turn of the century through the 1940s — and he remains one of only four authors to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction twice. His famous novels The Magnificent Ambersons and Alice Adams are both set in the Midwest, the former in his hometown of Indianapolis. Tarkington published several short stories with the Post at the height of his career, including “Francine,” a melodramatic account of a New York actress as talented as she is cursed with emotional extremities.

Published on December 12, 1925

Newspaper photographs of this present season inform us that Francine Lang, most piquant of all our stage ladies, has been shorn of the midnight tresses she knew how to wear in so many enhancing fashions. With every change in her way of wearing those lustrous undulations of hers, she seemed to produce a different type of beauty, almost a different woman, indeed; for the varying proportions of her head and the changeful framings of her face appeared to alter the very features themselves. But although you were never quite sure you knew what Francine Lang really looked like, you were always convinced that she was beautiful. She is beautiful still, even with all of this superb and useful adornment guillotined by the modern passion of women to fit themselves for the mechanical age. Yet when there are plenty of boys to look like that, it seems a pity to see a fine woman en gamine, with a boy’s head. It may be as well for Francine, perhaps, but it is not so well for the parts she plays. When her hair was long she had it coiffed in a different and appropriate way for every role, and so made it serve her art, helping audiences to feel that she was the person she played. Now it will be hard to make them forget that she is Francine Lang; but perhaps now she doesn’t want them to forget it.

She was never lovelier, I think, than when she played in Young Mrs. Tomlinson, that fragile comedy of feminine elfishness and masculine puzzlement. By no manner of means was Young Mrs. Tomlinson a great play, and certainly it was not uproarious in its comedy — as the stage reviewers, with a somewhat fatigued kindness, almost unanimously pointed out. But enough people liked it to keep it on for a season; and this was due, I had no doubt, to the quality of genuineness with which Francine Lang invested the title part. I had no illusions about the little comedy, which was one that Norman Archer and I had written for her — without Francine it was nothing. But with her it had its little day, and I have always been grateful to Young Mrs. Tomlinson for the opportunity it gave me to know her well.

At the time of the comedy’s production, however, I was less grateful for that opportunity than my collaborator was. Norman is of a warm, appreciative disposition, sensitive to everything, particularly to the sprightlier forms of beauty; moreover, he is volatile, and this was his first play. That is, it was his first to be actually put on; and of course he was excited about it and about everything concerned in it — naturally, most of all excited about Francine. His idea of the first thing to do, after we signed the contracts in her manager’s office, seemed to be that we should give a dinner for her.

He did give one, though I discouraged his enthusiasm for it as tactfully as I could, and evidently the new playwright and the star found each other sympathetic — I heard the next afternoon from one who had been a guest that it was quite a party, attaining that distinction not only through an orchestra, orchids, and terrapin.

Dancing stopped for breakfast, my friend told me at the Players’; and a lighthearted excursion in three cars to the country for over Sunday succeeded breakfast, my informant being the only one of the dinner party to find himself unable to extend his gay humor so far.

He was a member of the company engaged for Young Mrs. Tomlinson — leading man for Miss Lang, in fact ; by name George Morris — and he feared that too much liveliness might not prove a beneficial prelude for rehearsals, which were to begin on Monday.

“Old Zip won’t care much for it,” George said. “He’ll be pretty sure to hear about it too. He usually doesn’t miss hearing about much that goes on.”

He referred to old Cyprian Klebber, Miss Lang’s manager; and he was correct in his surmise, as I discovered that evening when the Old Zip came to my hotel rooms to peck as many tiny holes as possible in the manuscript of the play before it went into rehearsal. He was a bald, almost shabby little old man, with a frontal convexity, and his head was like a large pink fruit withered into the contour of features, with a pair of flawed large blue eyes glued carelessly among them. They never merely looked at anything; they always stared intolerantly, even at what could offend nobody; but I found them more aggressively upon me than usual when we had sat down with a table between us. It appeared that he held me responsible for the festivities Mr. Morris had described to me.

“You better send your young friend back to Oshkosh,” he said, speaking of the host of the dinner party.

“Norman Archer? He doesn’t live in Oshkosh,” I said. “He lives in Southern Virginia — when he’s home. Who told you about it?”

“George Morris,” old Cyprian said. “You send that fellow back to Oshkosh. Hasn’t he got any sense?”

“Not the kind you mean — no, not yet. It takes a little time, you know. Didn’t you find it so yourself when you were beginning?”

“No, I didn’t. I didn’t have any beginning, because I was born in the business — in a room up over the flies in the old Athenaeum, where we lived when my father was manager there. You better send your young friend back to Oshkosh.”

Thus he spoke and thenceforth continued to speak of my collaborator as if Archer had no stake in the play, but were merely a young friend of mine whom I whimsically kept about me for no reason and against all sensible advice. Old Zip would never admit him to be from anywhere in the world except Oshkosh, and when I urged that my young friend was quite as much and as competently the author of Young Mrs. Tomlinson as I was, and therefore entitled to a playwright’s legitimate connection with his own comedy, the old man’s streaky eyes would become a little more protuberantly intolerant and he would again stubbornly instruct me, “You tell him he better go back there.”

He refused to speak to Archer when the latter arrived at the theater on Monday morning for the rehearsal; but Norman was unaware of anything lacking, and from the first seemed conscious of the manager only as a bit of mechanism, probably necessary but unimportant, attached to this glorious new experience he was having. He drove up to the front of the theater in a fine large car he had hired, and thus offered us a picture of affluent and congenial gayety, for with him was Miss Lang. Norman was almost as prettily dressed as she was; and as she nodded merrily to Cyprian Klebber and me, where we waited in the lobby, the great cluster of violets she wore upon the breast of her blue coat sent us a hothouse sweetness plagiarized from springtime. Norman drew me aside.

“She’s absolutely as magnificent as I thought she’d be.” he said. “I’ve never met a woman like her — oh, anything at all like her! She’s been the life o’ the party simply every second for three days. We’ve had a royal time!”

“No doubt,” I said; and he perceived my dryness, which was a little emphasized.

“What’s the matter?” he asked. “It’s been merely a wholesome jolly good time in the sheerest comradeship. What’s wrong with that?”

“Nothing at all, Norman. I was only thinking of it as a question of advisability. Rehearsals and getting ready for an opening are a strain on everybody, and a three days’ and night’s party for the star — not to speak of four members of the company being along too I — ”

He interrupted me eagerly:

“But that’s one of the reasons a party like this is such a good thing. It takes their minds off their nervousness so they can come to their work all fresh. And of course for Francine herself it was just a godsend. That’s why I particularly wanted to do it — to take her out of herself. You know, of course, she’s been in the depths — actually tragic depths too — don’t you?”

“No, I hadn’t heard so. Klebber hasn’t mentioned it to me, and she doesn’t look it. What’s she been so tragic about?”

“Why, about her husband, of course.”

Norman had become serious; his voice deepened with commiserative sympathy.

“You knew about it, didn’t you?”

“I knew that she’d been getting a divorce, but not that it affected her so deeply as you say, Norman.”

He shook his head, implying that the facts were much gloomier than I might guess.

“It’s almost shattered her,” he said. “She’s been very near abandoning her whole career — in fact, she’s considered much more radical things than that. She told me so herself. I don’t mean exactly suicide, but at least giving up the world. She was actually just about on the point of doing it, Miss Yeats told me. Miss Yeats is her best friend in the company and Francine tells her everything.”

“She seems to tell you quite a little, too, Norman, for a rather short acquaintance.”

“Oh, but you see people get to know each other so well right away on a party like this, and especially in the profession,” he said. “That’s the beauty of it. And besides, I suppose I happen to be the sort of man women confide in — possibly because they think I have more understanding of them than I really have.” He laughed, then renewed his seriousness. “Miss Yeats said Francine might have thrown over her contract with Klebber and our play and everything, if I hadn’t happened to come along just when I did — I mean, happened to be sympathetic to Francine’s nature, and giving this party so that she’s had a chance to get her mind off her trouble long enough to restore her — her balance, as it were. You see, she cared for the man really quite desperately; she told me she had, herself. Miss Yeats says she cared for him more than she ever has for anybody; and Miss Yeats says she thinks she always will care for him and can never get over it, no matter how gay she may manage to be sometimes on the surface.”

“What do you think about it?” I asked, as he paused rather pensively, “Is that your impression too?”

“Well, no,” he returned conscientiously. “I think wholesome influences and — and her work, of course — and keeping her gay, so that the wound has time to heal — I think all that might get her by the danger point of becoming morbid. Miss Yeats says the night of the dinner was the first time she hasn’t cried all night since the divorce was granted. The man treated her with actual brutality. Francine worshiped him, yet he went back to England to play opposite a woman his wife knew perfectly well he’d been in love with for years. Miss Yeats said the dinner was the first time Francine’s shown any real interest in anything, and for her part, she regarded it as a life saver. As a matter of fact, Francine told me the same thing herself, and I don’t see your point in seeming to disapprove of my giving it.”

“I didn’t mean to express disapproval exactly,” I told him, “I was thinking a little about Cyprian Klebber. Every play is a risk, of course, and he’s risking quite a bit on this one of ours. You see, Klebber — ”

“Dear me!” Norman interrupted, and he laughed cheerily. “You’re not worrying about that old winter apple, are you? What’s he got to do with my having a wholesome good time? “ He seized my arm. “Come on! I don’t want to miss any of my own first rehearsal. It’s the life, isn’t it?”

He seemed to prove that it was certainly the life for Norman Archer — during the next six weeks, at least. Probably there never was a playwright who brought to the more arduous and trying division of his task a lighter heart or a more enraptured interest. When, after some of the rehearsals, we would set to work upon changes in the manuscript, he seemed to be in a happy trance, from which he would waken with what was frequently a useful bit of criticism; but usually, when this sort of work was called for by an afternoon rehearsal, he put it off until he could take Francine to tea somewhere, and then might again postpone it until they had dined and been to a theater. Sometimes they asked me to accompany them, and — although when I did, the interchange of comradely gayeties between them made me feel a little old and unwieldy — they took the sprightliest pains to make me feel included — included, at least, in a somewhat unclelike capacity.

But there were times when, in the midst of her prettiest laughter, Francine’s exquisitely mobile face would become abruptly blank, almost haggard. She would sit silent, her eyes fixed broodingly upon some unhappy distance beyond the inclosing walls; tragedy seemed to poise upon the white brow of Columbine. “Thinking of him!” Norman might whisper to me; but upon the instant the spell would pass; Francine’s eyes would look like dark water sparkling out into sudden full sunshine; she would catch up her laughter where she had left it, and the universe would again be a merry place for both Norman and me. Inevitably I grew to be fond of her, because no one could be with her much and not grow fond of her. Her loveliness of person was one reason, and a good one, for it was a kind loveliness. The beaming sweetness of it, was genuine, as many a worthy and many an unworthy applicant for help well knew. She understood nothing at all about what is called the value of money. She worked hard for it, and then gave it all away. Kindness — the most touchingly untutored passionate kindness — was her great failing, I think, and the cause of most of her troubles.

Without question it was the cause of some trouble for poor Norman too. His eager delight in being with her, and her kindness in appreciating that delight so profoundly as she did appreciate it, of course brought about the expectable result. By the time we opened they were inseparable — so much so that their comradeship had become a matter of course with the Young Mrs. Tomlinson company.

“When you want to see her, find him,” George Morris said.

“But with me,” I suggested, “it’s rather more a case of ‘to see him, find her.’ “ George stared at me.

“I don’t want to see him,” he said enigmatically; and I was too busy just then to ask him to explain.

Klebber arranged for us to open in Joliet, Illinois, a preliminary excursion of the customary sort, to find out what effect an audience not necessarily fatal might have upon our comedy; and the company left New York three days before this trial. At the last minute I was prevented from leaving with them, though Norman could not understand how I was able to let even a celebrated eye specialist interfere. My young friend was radiant with his present happiness and his expectation of more. He had bought violet boutonnières for us both — for the train, he said — and he was sure Francine would be broken-hearted by my absence from the great excursion. In fact, he was so solicitous that he dashed off and brought her to the hotel to say good-by on their way to the train.

“Don’t let that awful man make you sit in a dark room for a month,” she said. “I can’t bear to think of it for you — especially at such a time.”

Her kind eyes became instantly more beautiful with moisture, and to my awkwardest astonishment she even kissed me. Then she turned and went out sorrowfully; but just beyond the door her steps were heard to quicken. She romped down the corridor with Norman, and I could hear them laughing happily together as they waited for the elevator.

My oculist proved not so formidable as he had thought he might need to be. At the last moment he let me go out to the premiere of Young Mrs. Tomlinson upon the condition that I return to him in New York at once, and I arrived at the hotel in Joliet just three hours before the rising of the first curtain upon Young Mrs. Tomlinson. Cyprian Klebber, so intolerant as to appear inflamed, met me as I turned away from the clerk’s desk after registering.

“He’s gone back to Oshkosh,” Old Zip informed me harshly. “You’ve certainly played the devil with this show.”

“How could I? I’ve just this minute got here.”

“He’s gone back to Oshkosh, I tell you!” Klebber appeared to think that this explained everything.

“I’m not a mind reader, Cyprian,” I said, falling back upon this old stencil of repartee. “Be more enlightening, if you can.”

“I can, all right!” he assured me with undiminished ferocity. “If he was going back to Oshkosh, why in the name of common sense didn’t he go when he’d ought of? Not him! He had to wait till it would ruin the show. I told you exactly how it was to be, didn’t I?”

“You always do,” I replied, and at least it was true that Old Zip, after any catastrophe, has never in his life failed to ask that question. “I incline to gather that Norman Archer has gone back to Virginia.”

At this he almost screeched at me, “He’s gone back to Oshkosh! How many times do I have to tell you?”

“Why did he leave, Cyprian?”

“He got a telegram his little boy was sick with scarlet fever and left on the noon train. We’re not going to give any show tonight — nor no time at all. Everything’s over!”

“Aren’t you flattering Norman?” I asked. “It’s a surprise to me that you regard the presence of any playwright whatever as of such importance. I thought you didn’t want him about at all.”

“Me!” he exclaimed. “Want him? I’d give five thousand dollars this minute if he’d never left Oshkosh. She’s about got the roof off of this hotel right now.”

“Francine? What’s the matter with her?” He laughed with a wearied bitterness.

“Oh, nothing — except she isn’t going to play tonight or any other night. She’s through with the stage permanently.”

“Why is she?”

“Because he’s gone back to Oshkosh.”

“What?”

He waved his arm impatiently toward the elevator.

“Go on up and talk to her. Number 24, on the next floor. You can’t do anything; but she says she wants to see you, so go on up and go crazy.”

The sympathetic Miss Yeats opened the door numbered twenty-four and admitted me to the outer room of our star’s apartment. Francine was not visible, but became audible instantly when she heard me inquiring for her.

She called from the next room, “Has he come? Is he there?” And before Miss Yeats could answer she came rushing in.

That piquant face of hers, so cheering in its lighter moods that just to have the twinkling edge of a smile from her lifted one’s spirits for hours, was now all plastic with anguish. She ran into the room, but not quite to me; for she stopped herself suddenly a few feet away, stared at me as with a piteous incredulity, and then lurching forward, threw her arms about me and wept loudly upon my breast.

“You are his friend!” she cried; and her voice, strained with a pathos unbearable to hear, seemed to express the tearing of emotions beyond the power of ordinary creatures to feel. “Tell me the truth — all of it — all of it — all of it!”

Miss Yeats helped me to get her into a chair and brought her some ammonia in a glass of water. Francine cried upon her friend’s fingers as the glass was held to her lips.

“I want just the — just the bitter truth,” she wailed. “You are his friend — you must tell me and not spare me. Will you tell me just the truth?”

“My dear, I’d try to, if I understood what it is you want to know.”

“Don’t you?” she said feebly; and then, after applying to her eyes and forehead a damp towel, brought to her by the faithful Miss Yeats, she seemed to regain a better composure. She looked at me accusingly, almost with hostility. “You were with us often enough to see what I was beginning to feel about him. You know you saw. Why did you let me go on with it? Why didn’t you tell me he was married?”

“I supposed you knew it. In fact, I was quite sure you did. Didn’t you?”

She touched her eyes again with the towel before replying: “I knew — I may have known he was married, yes; but I didn’t — I didn’t suppose he had a wife.”

“I don’t quite — ”

“No, I suppose not,” she said, and laughed miserably. “It sounds crazy, doesn’t it? I mean I never dreamed he could be living with her. How could I have dreamed that he was?”

“But why not? What led you to suppose — ”

But at that she jumped up fiercely, facing me.

“Did he ever talk about her to me? What leads any woman to suppose such a thing?”

I stammered, “I — I’m afraid Norman is a little romantic.”

“Romantic?” she cried. “Does that explain it? Romantic? Is it merely romantic to break a woman’s heart? Is that all it is — romantic — to make a woman care for you — to make her love you more every day, and more and more — and then do what he’s done?”

“You mean his having to go home on account of — ”

She interrupted me, and her voice was loud and harsh. “I knew he was married, yes; but I didn’t know he had a wife and three children!” She advanced upon me, hurling the towel from her and overturning a chair that stood in the way.

“I knew he was married; but do you suppose I ever dreamed he was just a regular little family man?”

“But I don’t — ”

“He is!” she shouted. “That’s what he’s turned out to be — a regular little family man who has to bring home a beefsteak in the evening, and can’t even stay for my first night in his own play because one of the children’s got the colic!”

“It’s scarlet fever,” I ventured. “It isn’t — ”

She screamed in my face, “What do I care what it is?” Then she drooped before me, weeping again. “Ah, dear God! Why is it I’m the sort of woman that men can treat as they do treat me? Why couldn’t I be like other women? No other woman has to suffer as I do. Men don’t treat other women as they do me.”

I took her hand. “You poor dear child!” I said. “Men don’t fall in love with other women as they do with you. I’m afraid the trouble is that we all fall in love with you, Francine; and among the lot of us you’re bound to find a few who are — well, in predicaments, so to speak, like poor Norman.”

“Poor Norman?” she echoed mockingly, and snatched her hand away. “Are you pitying him? Good heavens, he’s gone off to his wife and children and he’ll stay there too! He belongs perfectly in his little home and I never want to see him again! I asked him, ‘But can’t you stay just a few hours longer — until I’ve played this part for you? Not even just these few hours?’ Not he! His wife had telegraphed for him! He couldn’t stay a minute because the baby had the colic! Nice for me, wasn’t it?”

I made another effort to soothe her a little, but of course it was of no avail. She had begun to walk up and down the room with great strides, her hands continually flinging out from her and up and down in a gesturing so vehement that her heavily ringed fingers sometimes struck the wall or the mantelpiece or the back of a chair.

“I suppose he thought I was used to being treated like this! He knew what my husband had done, and he knew it had almost killed me; but I suppose he thought if I could stand that I could stand this! He thought I was iron, probably! Iron, that’s what they take me for!” With that she struck herself violently upon the breast with both hands together, and laughed wildly. “Iron! That’s what he takes me for. Iron! Iron!”

“Francine,” I said sharply then, “you’re doing yourself no good by letting yourself go like this. Already you’re hysterical, and if you don’t quiet down you won’t be in condition to give a performance tonight.”

She whirled upon me.

“What?” she cried.

“There isn’t too much time,” I said, “before the curtain rises.”

She looked at me insanely, her eyes opening wider and wider until incredible spaces of white showed both above and below the staring pupils. “Dear God!” she whispered hoarsely. “He expects me to play tonight! What are men made of? He expects me to play tonight!”

“Francine, that curtain — ”

She screamed, “Oh! Oh! Oh!”

“That curtain — ”

“No!” she screamed. “No! No! No!” Her high-pitched voice grew louder and higher with each repetition of the word until the sounds she made were only sounds, not words. Then she gasped at me, “What are you made of?” and sank down before me upon her knees. Rocking herself backward and forward, her tortured.head in her hands and a very waterfall of tears upon her cheeks, she moaned, “Never! Never! Never!”

She pitched sidewise, her hands clutching at the rungs of a chair; and her glorious hair came down and hung upon her like the black robe of tragedy’s own self — a piteous and a beautiful sight to see, and somehow more heartbreaking than all her tears. It was always that splendid fallen hair of hers that I remembered afterward — its curtaining darkness inclosed and muffled her weeping, yet seemed itself to weep for her so eloquently.

Miss Yeats motioned me to be gone, and indeed it was high time. The door opened quietly before I reached it, however, and little old Mrs. Watkins, the grandmother comédienne of the company, came in. She was eating an apple; but as she saw the stricken figure upon the floor, her experience of scenic harmonies prevailed with her. She shifted the apple to her left hand and held it behind her, as she went forward to offer her right for the assistance of Miss Yeats with Francine.

Then, with the door half closed behind me, I heard a cough of the kind that says, “Look back!”

I did. The cough came from Mrs. Watkins; she and Miss Yeats were supporting Francine, moving with her toward the other room; but both of them were looking back at me over her shoulders. Miss Yeats nodded reassuringly, and the left eye of Mrs. Watkins closed tightly in an earnest communication. Her practiced lips formed inaudibly, but with perfect distinctness, the message:

“She’ll be all right!”

I was not fully able to believe it, and there were some anxious moments behind the curtain two hours later; but that long experienced and excellent actress, Mrs. Watkins, knew what she was talking about. She knew because she remembered what fine performances she had given every night, two years before, when that noble old comedian, Ted Watkins, her husband, lay dying. She had been in love with him when they were both twenty-two; she was in love with him when they were sixty-eight; they were models of lifelong devotion — for of course such models are found upon the stage as beautifully in perfection as elsewhere — but she played, and played well, every night of his last illness, which was what he expected of her.

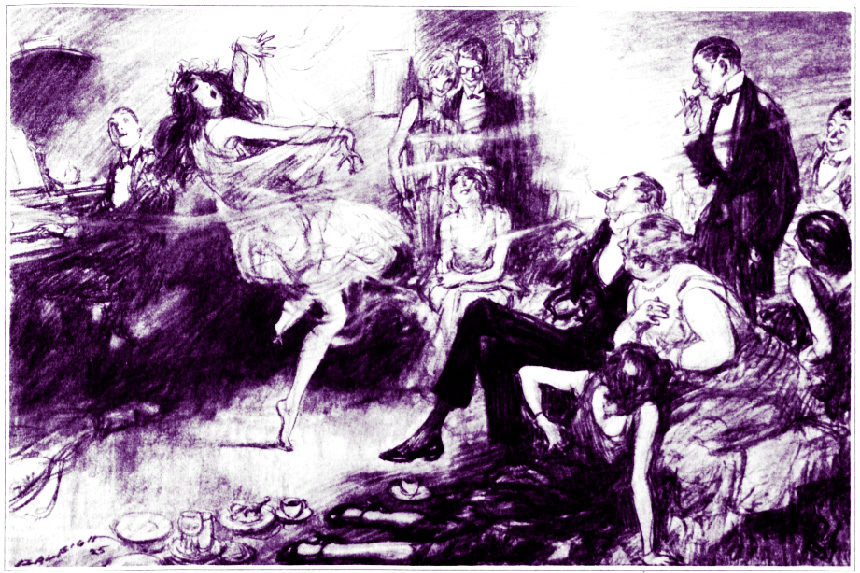

We whose orbits revolve about actors — we playwrights, managers, stage directors, electricians, carpenters and workmen, intimate witnesses behind more kinds of curtain than the painted one — we who are a part of the actors’ lives and fellowship, but never quite of their blood brotherhood — we grow used to seeing them give way to the uncontrollable expression of uncontrollable emotion; yet some of us never cease to marvel at their self-control when their hour strikes and that painted curtain rises. Our own, ascending that night in Joliet, disclosed Francine Lang as the very soul of rosy comedy, the merriest of mischiefmaking sprites in all the world — Young Mrs. Tomlinson to the life.

Audacious, as charming as her own laughter, wistfully humorous and wistfully tender, too, in the pretty love scenes with good-looking George Morris, she carried it through to the end, and that audience, at least, was won for us — altogether by Francine. Most of the men in the house were in love with her, I am sure, before the evening was over, and for women she was always a kind of intoxication. They passed out through the lobby, glowing, chattering about her, and already imitating unconsciously the fascinating little vivacities of her comedy voice.

Cyprian Klebber had somehow gathered the materials for a supper in his own rooms at the hotel, after the play, and for once in his life found nothing to be done upon a manuscript after a premiere. Francine was the life of the party!

She was almost uproarious at times, and certainly made the rest of us quite so. She did her imitations; she sang for us, with George Morris at the piano; and finally, toward daylight, gave us the most artfully ridiculous of her mockeries, a burlesque — not at all old-fashioned in propriety — of modern interpretative dancing. Old Zip kissed her rapturously and announced that the party was ended upon that jovial climax.

“A little celebration, if it comes just once and after the play goes over — and if it’s mine,” he said, “it’s all right!”

I bade them all good-by, for I was to start back in the morning to my oculist, and I came to Francine last. She took my hand warmly in both of hers, giving me a liquidly grateful long look from deep within her eyes.

“You’ve been — you’ve been such a comfort!” she said in a broken whisper.

How on earth I could have been thought a comfort was beyond ordinary powers of comprehension, but Francine was ever unfailing in her surprises for me.

When I got back to New York the eye specialist reversed himself and kept me in a darkened room for a while; then he sent me to other specialists, and the end of it was one of those ocean voyages for general tuning up, and some months on the shores of the Mediterranean to preserve the pitch to which I was supposedly tuned. When I returned to New York, in March, Young Mrs. Tomlinson was in the midst of its mild success at old Cyprian’s own theater, the Klebber, and a night or two after I landed I renewed my acquaintance with it.

Francine was more interesting, as well as more charming, than ever. She was one of those careful artists who never stop studying; and she had added to the part a multitude of tiny significances — bits of acting, of business that enriched the original portrait with a patina of reality. She showed the greatest zest, I thought, in these enhancements of the illusion she so lovingly created; and I was sure that she must herself be in as high spirits as Mrs. Tomlinson appeared to be. It pleased me to think she had wholly recovered her sentimental poise again; and although I felt that any woman who had suffered as I had seen her suffer could never be without at least the scar of such a wound, I imagined that she had made herself able to think of Norman Archer, if not without pain, certainly with philosophy. But as I returned from the smoking room to my chair in the orchestra before the curtain rose upon the final act an usher brought me a note from her that made me fear I had been overoptimistic:

“Please don’t leave the theater without coming round to see me. You are always so comforting — and I am in need of you for that.”

She was waiting for me outside the door of her dressing room, still in Mrs. Tomlinson’s ball gown, to say nothing of Mrs. Tomlinson’s complexion; and she smiled wanly as she gave me her hand and led me into the room.

“I’m always sending for you when I’m in trouble, I’m afraid,” she said as we sat down. “Did you think I was any good at all tonight?”

“What a question! You were so much better than the part we wrote for you, poor Norman and I — ”

She leaned forward and for a moment put a gently entreating hand upon my arm.

“Don’t — please don’t speak of him.”

“Forgive me,” I said. “I’d hoped all that had passed — at least so far passed that you could hear his name mentioned without pain. I’m sorry — and yet I can’t be very sorry about anything just after you’ve given me so much happiness as you’ve been giving me all evening. You’ve made the inconsequent skeleton of a role that we gave you into something so vivid and brilliant that it’s the greatest delight in the world to sit and watch you building it up as you did tonight. The very moderate truth is that you were glorious.”

She looked at me fixedly for a long moment, while a large and bright tear rose upon each of her lower eyelids, poised, increased, and then glistened down her coated cheeks. Too fatuously I thought my praise had touched her.

“It’s quite true,” I said.

She shook her head and more tears came.

“I wonder how I do it,” she murmured brokenly.

“Wonder how you build up such a part, Francine?”

“No; I wonder how I act at all. I wonder how I go on with it night after night. I wonder how much longer I can go on with it — and this pain in my heart stabbing deeper and deeper every hour of the day and night.”

She spoke with the trembling and hopeless pathos that wrings the heart of any listener, even if he be a tired playwright or manager. Certainly my own rather hidebound sympathies were moved for her.

“My dear,” I said. “If there’s anything in the world I can do — or say — ”

She jumped up, her arms for an instant high above her head; then she brought them down with the palms of her hands upon her wet cheeks.

“No,” she said. “Nobody can help me. It’s all my fault for being born — I can’t see any other reason. I was just born to be a woman that men treat as they treat no other women! Why is it? What’s wrong with me?”

“With you? Good heavens, nothing!”

“But there is!” she cried passionately, and flung her arms wide, facing me, as though she asked inspection to determine her defect. “There must be! How can there help being something wrong with me when I always suffer for the one reason? Never any other!”

“What reason, Francine?”

“The one you know — the one you’ve seen.”

“But I haven’t — ”

“You have!” she cried. “Why is it that when I care for any man, as soon as he’s told me he cares for me I find he’s in love with some other woman and at her beck and call? Why is it?”

Puzzled to reply, I fear I was about to stammer out something about a case of scarlet fever not being mere beck and call precisely; but her inquiry was a rhetorical one. She expected no answer, even though she went on asking the question.

“Why is it? What is it about me that makes a man fall in love with some other woman as soon as he’s made me fall in love with him? For that’s what they do! You know it, don’t you?”

“Indeed I don’t,” I said; and thinking it a little distracted of her to suppose that Norman’s affection for his wife had never been exhibited before his departure to the sick child’s bedside, I tried to set her right about that. “It doesn’t seem to me you’re any more accurate about men, Francine, than you are when you suppose there’s something wrong about yourself. Of course I don’t assume to know what he gave you to understand about his feeling for you; but naturally, under the circumstances, it was a subsequent feeling — he must have cared for her long before he ever met you.”

“What? He did nothing of the kind! He never gave her a thought! And at last a little real happiness seemed to be coming into my life — for the first time. I’ve thought I cared before, but it was all the emptiest illusion until I began to see that he cared for me. And just as soon as that happiness came to us both — to him and to me — she spoiled it! Every soul in town knows it! Don’t pretend no one has told you. It’s the first thing you’d hear, and you couldn’t deceive me about it — not for an instant!” She grew more vehement in voice and gesture with every word, and I was unable to interrupt her, though I tried. “Don’t tell me you don’t know what I know you know! Every soul in the company tells it! The box-office men tell it! Cyprian’s stenographers tell it! The stage hands tell it! Is there anybody in all New York that doesn’t go about telling how he jilted me?”

“Francine! How could there be any question of that?”

“How?” she cried. “How could there?” And to my dismay she burst into a loud and gusty sobbing. “Ah, dear God!” she wailed. “Could there ever be any question of such a thing’s not happening to me? And I was so happy! I was! I was — happy!” And upon hearing this word sobbed out in her own voice, she uttered a pealing laughter, disturbing to hear, took her head between her hands and moved it from side to side as if it were upon some agonizing hinge and must be worked free. “Happy!” she cried. “I tell you I was happy! And then I found out that five nights of last week, when he told me that his old mother was in town and he had to be with her, he was taking Isobel Yeats out to supper! Five nights! Five in one week!”

“But it’s impossible,” I said, and in my bewilderment thought it might be a good thing to take my own head in my hands and rock it. “He isn’t here! He hasn’t been here since — ”

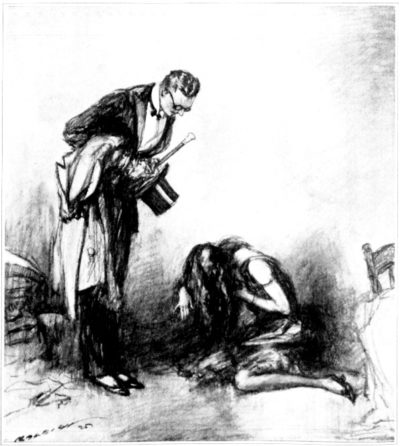

“Not here!” She stared at me wildly. “I wish he weren’t! Only yesterday — I was so happy — so, so, so happy!”

Her voice broke upon this; she seemed about to faint; but before I could reach her she staggered back against the wall, slid downward against it, her outflung arms pressed against it. She crumpled finally, half sitting, half kneeling, upon the floor at my feet. Her loosened hair fell in all its magnificence from her bowed head, covering her face from me, a beautiful black shroud over her despair. Her voice came from beneath it, choked, liquid with weeping, desperate with intolerable anguish.

“George is just killing me!” she sobbed.

Of course it was George Morris she’d been talking about all the time!

I called her maid in and waited outside the dressing room until Francine came out, which she did briskly, and looking what is sometimes called heavenly, not more than twenty minutes later. She made me go to supper with her at a supper club, where she laughed never so lightly, was witty with many friends, and finally went so far as to make me dance with her, though that is not possibly to be considered desirable for any lady whatever — happy or unhappy. Late, indeed, I left her at the elevator in the apartment house where she lived.

“You’re always such a comfort!” she was so kind as to tell me, and gave me a deep look of the saddest gratitude before she turned, beaming, to the electrified elevator man.

She married George Morris the next June; but George never had been what we call steady — a word, of course, implying the quality of constancy. The effect of his good looks upon the impressionable was something with which he had not humor enough to contend, and he was always in a more or less urgent state of siege. Perhaps the problem too often presented him by the necessity of being in two or even three places at the same time, and of accounting to his wife for being in any of them at all, was too much for him; at any rate, no one thought him eccentric when he took earnestly to drink.

After Mrs. Morris finally decided upon the legal process that was inevitable from the moment she said “I will” to George, it was the faithful Miss Yeats who wrote me, at Francine’s request. For, except upon the occasion of those five suppers — a merely light-headed matter — Isobel was always Francine’s most intimate support, both on and off. Their reconciliation, in fact, had taken place on the day following my bewildering interview with Francine in her dressing room.

“She has lost her happiness,” Miss Yeats wrote. “She walks the floor and wrings her hands night after night when she comes home from the theater, and she declares passionately that she will never play another part after this season is finished. She is determined to retire permanently from the stage, and the truth is she is in such utter despair as I have never seen. And yet — and yet — well, I do not believe she will give up her career. What is more, although she suffers dreadfully, I believe when you next see her from out in front you will not believe that her sorrow has affected her art. That is something that will be greater than ever.”

I was sure Miss Yeats was right about Francine’s art. And yet when I saw the newspaper photograph of her with her hair all shorn away, and remembered how eloquently she had always used those beautiful histrionic tresses, even in her most private rehearsals, I fell into a melancholy musing. It seemed to me that a barber might do to Francine’s art what despair could never do.

Illustrations by Henry Raleigh/SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now