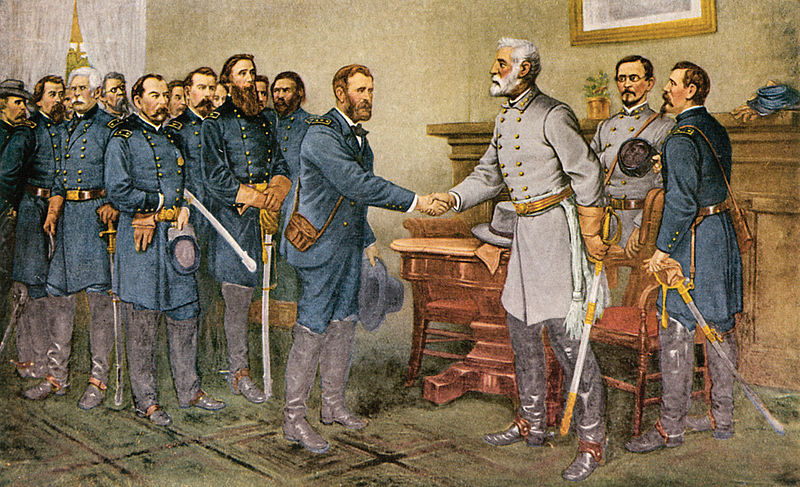

The conventional narrative of the Civil War is that it ended when Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Court House, or perhaps a month later when Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured in Irwinville, Georgia. But the true final action of the American Civil War began in Palmito Ranch near Brownsville, Texas, two days after Davis’s capture nearly 1,000 miles away.

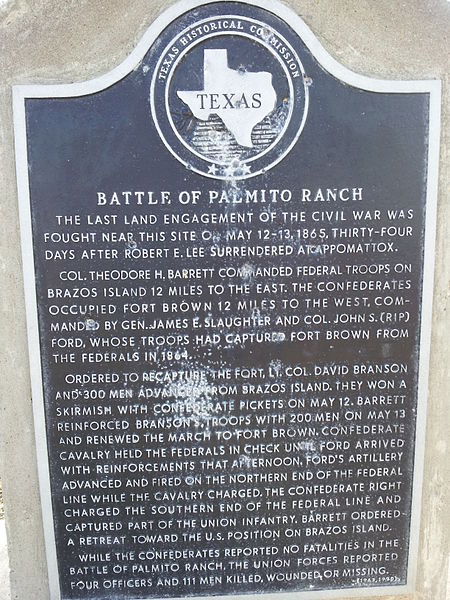

To be fair, the end of the Civil War was confusing and opaque. Although Lee did surrender his massive Army of Northern Virginia to Grant on April 9, 1865, at the Appomattox Court House, there were still hundreds of thousands of rebel soldiers motivated to fight for the Confederate States of America. It took nearly three more weeks for the Union to compel the vast Army of Tennessee commanded by Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston and other rebel forces numbering nearly 100,000 to surrender on April 26, 1865. And even after Confederate President Jefferson Davis was imprisoned in May, the Union still had a way to go until the war could be considered finished. Over a year after Lee’s surrender at the Appomattox Court House, President Andrew Johnson announced the end of the Civil War on August 20, 1866. Although the war officially ended in late summer of 1866, the Battle of Palmito Ranch was the final armed conflict of the war and ironically resulted in a Confederate victory in southern Texas.

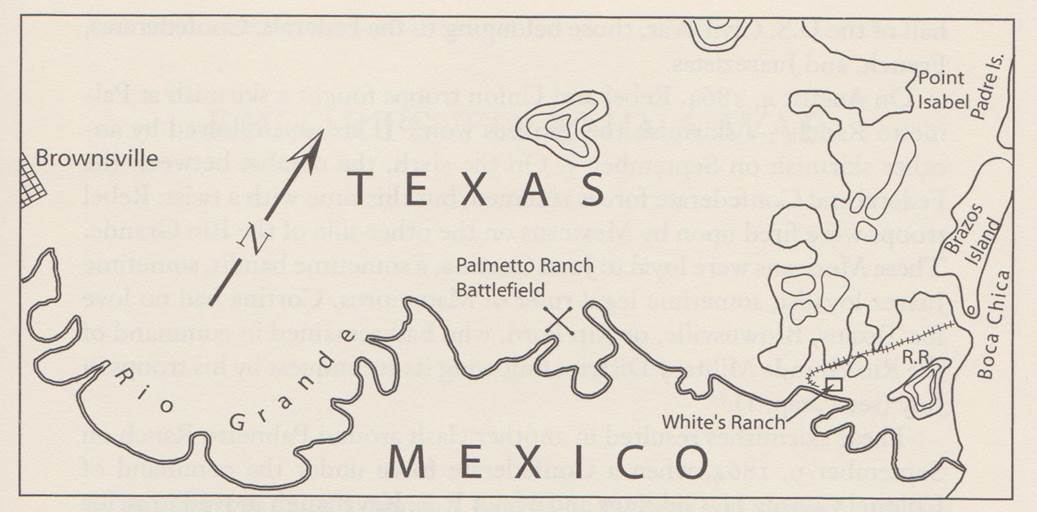

Although most of the high-profile battles of the Civil War occurred in the Mid-Atlantic and the South, southern Texas was an important theater for both the Confederacy and the Union. The ports of Brownsville and Corpus Christi were key players in the international cotton trade, on which the Confederacy was extremely dependent. If the Confederacy were to lose such ports, their economic viability would plummet, and their war efforts would effectively grind to a halt. Understanding the importance of Texas ports, Union Major General Lew Wallace coordinated a meeting with Confederate Brigadier General James E. Slaughter to discuss a ceasefire and truce in the Texas territory in early March 1865. After informally coming to an agreement in which Union officials promised no retaliation against Confederate soldiers or leadership in return for their surrender, Slaughter informed his superior, Major General John G. Walker, of the proposal. Walker irately rejected the terms of surrender and severely chastised Slaughter for even entertaining the meeting. Even after Slaughter’s blunder, the two adversaries implicitly honored their ceasefire, declining to engage in armed skirmishes for the following two months.

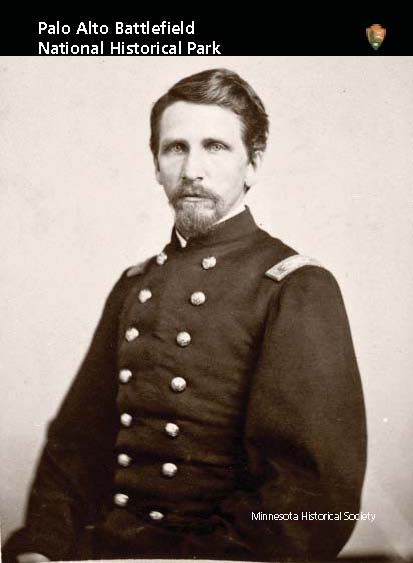

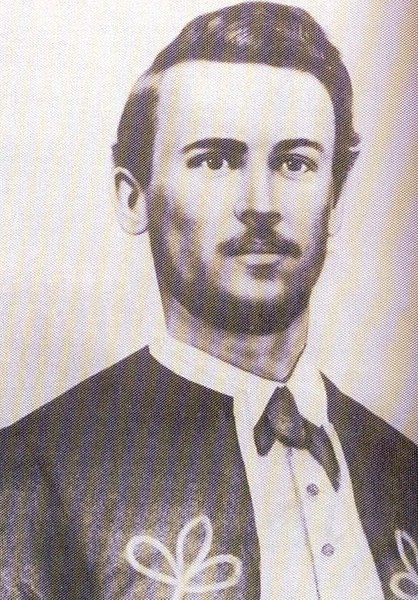

According to the Texas State Historical Association, a passenger on a ship headed north on the Rio Grande River threw a copy of the New Orleans Times newspaper to a group of Confederate soldiers outside of Palmito Ranch on May 1, 1865, alerting them to Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln’s assassination, and the impending collapse of the Confederacy. This news prompted hundreds of Confederate soldiers to leave their assignments and head home. The exodus left only the most resolute soldiers who were most committed to the Confederates’ commitment to slavery and independence from the Union. After receiving intelligence of the mass departure of Confederate troops, 30-year-old Union Colonel Theodore H. Barrett believed it was the opportune time to prove his legitimacy as a young commander and take the port of Brownsville for the Federals.

On the evening of May 11, 1865, Barrett ordered 250 men from the 62nd U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment and 50 men of the 2nd Texas Cavalry Regiment to overtake a Confederate outpost called White’s Ranch. However, after arriving at the outpost at 2:00 a.m. on May 12, the Union brigade found no one there and decided to spend the night at the abandoned fort. After being spotted by Confederate allies, the Union soldiers set off to ambush a Confederate station at Palmito Ranch. At first attempt, the Union forces were successful in their attack, forcing the Confederate troops at the fort to scatter upon arrival. By midafternoon, the Confederates had returned with a much larger force, compelling the Union troops to retreat back to White’s Ranch. Barrett joined the Union forces after their retreat with 200 additional men from the 34th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. Barrett ordered his troops to march back to Palmito Ranch but was met with immediate fire, which drove the Union forces to seek cover in the bluff of the Rio Grande River. The rebels took advantage of the Union’s run for cover and sent a large cavalry force armed with artillery to bombard the Federal front until Barrett ordered a full retreat. This retreat marked the end of the final battle of the Civil War and a decisive Confederate victory.

Reporting of the causalities suffered during the Battle of Palmito Ranch range widely from as little as four to up 30 Union soldiers killed during the battle. Private John J. Williams of the 34th Regiment Indiana Infantry died on May 13 at Palmito Ranch and is widely considered the last soldier killed during the Civil War.

Civil War engagements west of the Mississippi River such as the Battle of Palmito Ranch are oftentimes overshadowed by more prominent altercations across the east such as the battles of Gettysburg, Bull Run, and Antietam. Even though the western front of the Civil War is often left out of the mainstream narrative, its history is rich and fascinating. In her book The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native People in the Fight for the West, Megan Kate Nelson outlines the complications of the Civil War in the southwest. She explains how the 1862 annexation of the Arizona territory by Confederate President Jefferson Davis played directly into the rebels’ goal of acquiring a port on the west coast and also to act as an expansion of their “empire of slavery.” In fact, the first Confederate invasion of Union territory occurred two years before the Battle of Gettysburg when Confederate Lieutenant Colonel Joseph R. Baylor led hundreds of Texan rebels into the Union-held territory of New Mexico.

The Union’s campaign in the southwest was also more complicated than their eastern endeavors. Although the Union was fighting to stop the Confederates’ expansion of slavery at all costs, according to Nelson they “simultaneously embraced slave emancipation and Native extermination in order to secure an American empire of liberty.” This harsh moral contradiction paved the way for American Manifest Destiny and the decimation of Native populations across the west.

The western front of the Civil War and the Battle of Palmito Ranch represent two important narratives of the Civil War that oftentimes get glossed over or completely ignored. The Confederate victory at Palmito Ranch along with the numerous Confederate monuments that can be found across the southwest serve as poignant reminders of the ways in which certain ugly histories of the Confederacy and the Civil War are forgotten today.

Featured image: Diorama of The Battle of Palmito Ranch (Source: Texas Military Forces Museum, Camp Mabry, Austin, TX. Used with permission.)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now