Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

On May 23, 1861 — six weeks after the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter — a statewide referendum in Virginia confirmed the Ordinance of Secession that Virginia delegates had passed on April 17 of that year. Virginia no longer considered itself part of the United States of America.

That very night, three enslaved Black men — Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend — snuck away from Sewall’s Point, where their owner had them making preparations for war, commandeered a boat, and fled to Fort Monroe, which still flew the American flag, seeking asylum.

The next day, Maj. John Cary of the 115th Virginia Militia arrived at the fort under a white flag. Those three men, he claimed, belonged to Col. Charles Mallory, who was in charge of the 115th’s artillery company. Cary asked that the slaves be returned. At the time, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was still in force. It stated that escaped slaves who fled from slave-owning states to free states were to be returned to their owners, so Maj. Cary’s request was not unreasonable.

The man in charge Fort Monroe, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, was no abolitionist, but he understood that most of the men under his command were, and returning the escapees to bondage would sow discontent among his troops. He faced a dilemma: Abide by his Constitutional duty and abandon the principles of his men, or grant asylum and give his enemies legal ground to retaliate.

Luckily, in civilian life Butler was a Massachusetts lawyer; he found a third possibility, and a solution.

He told Cary that he intended to hold the men. The Fugitive Slave Act, he stated, applied only between states. Because Virginia had seceded, it was therefore a foreign nation, to which he had no Constitutional obligation to return escaped slaves. Furthermore, Butler added that he would keep the men “as contraband of war, since they are engaged in the construction of your battery and are claimed as your property. The question is simply whether they shall be used for or against the government of the United States.”

He also offered a compromise: “Though I greatly need the labor which has providentially come to my hands, if Col. Mallory will come into the fort and take the oath of allegiance to the United States, he shall have his negroes, and I will endeavor to hire them from him.”

Of course, he knew Mallory would never switch sides, and Cary went back to his camp empty-handed.

Legally speaking, Butler’s maneuver didn’t free these three men but made them property of the federal government. That word he used, contraband — tracing to the Latin contra- “against” and bannum “decree” — was, until Butler’s utterance, primarily used in maritime law to describe illegal items that were subject to seizure by authorities. Butler’s argument treated these three “confiscated” men on the same level as a cannon or muskets seized from an enemy combatant: A military company was under no legal or ethical obligations to return war-making apparatus to the enemy.

Here at the beginning of the war, many in the North were more concerned with keeping the Union together than with abolishing slavery. For abolitionists, though, the end of slavery was front and center. But here, Butler had provided a solid rationale that brought the two outlooks together while sidestepping the longstanding questions about the morality of slavery.

Once news got out about Butler’s “Contraband Decision” (and it spread quickly through the North and among the enslaved in eastern Virginia), the word found a new life. Contraband became a widespread slang term for an escaped slave.

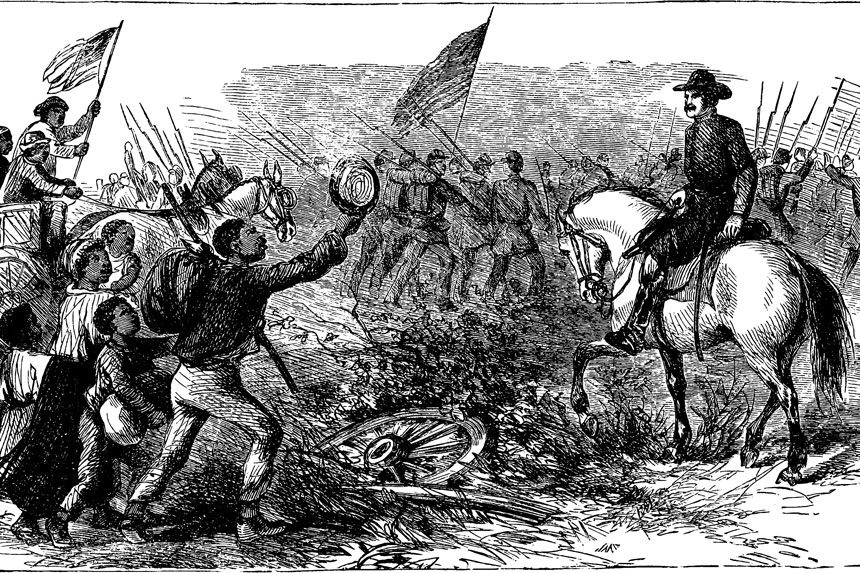

And the word was everywhere. A Philadelphia composer named Septimus Winner composed a piano solo called “Contraband” and dedicated it to Maj. Gen. Butler. Louisa May Alcott in 1863 published the short story “My Contraband,” about a white nurse and a freed slave in the Union Army. Painters like Vincent Colyer, Thomas Waterman Wood, and Winslow Homer crafted artistic depictions of freed slaves and named the works Contraband.

To some in the North, referring to escaped slaves as contraband was a tongue-in-cheek way to thumb their nose at Southern slaveholding rebels. But it served a more important social role as well: Northerners who were reluctant to call former slaves freemen found a more palatable alternative in contrabands — people who were not quite free, but not enslaved either.

And to those enslaved in the South, the word contraband became synonymous with freedom.

There were some objections to the term. Some rightly claimed that calling men and women contrabands was demeaning — Frederick Douglass, for example, was not a fan. But they had to admit that contraband was a step up from slave.

According to historian James McPherson, Butler’s Contraband Decision “turned out to be the thin edge of a wedge driven into the heart of slavery.” Butler’s fleeting argument to justify giving sanctuary to three men became the impetus and driving force to push the Union government to make slavery a larger issue of the war. It greatly influenced the passage of the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862, which authorized the seizure of any Confederate property, including slaves, that might support the rebellion. And it was an important paving stone in the road to Pres. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

Though it stood on a peninsula entirely within the Confederate state of Virginia, Fort Monroe remained in control of Union forces throughout the Civil War. It became an outpost of freedom to those attempting to escape slavery. To thousands of men, women, and children, escaping to Fort Monroe to become contraband was a huge step toward, ultimately, freedom and American citizenship.

Today, Fort Monroe is known to many as the Ellis Island for African Americans. Like Ellis Island, thousands of citizens can trace their family’s history through this single location. Standing in support of connecting Fort Monroe descendants to their family heritage is the Contraband Historical Society, a nonprofit organization whose mission is “to research, preserve, and promote the history, legacy, and contributions of the formerly enslaved, who were considered ‘Contraband’ of war.”

Words have only as much power as we give them. But when Maj. Gen. Butler chose the word contraband, this Massachusetts lawyer — a Democrat who had supported Jefferson Davis as his party’s presidential candidate in 1860 — hadn’t intended to imbue it with such force. In fact, he later referred to his use of contraband of war as “a poor phrase.”

Nonetheless, the word had the power to refocus the war effort, to catalyze the anti-slavery movement, and to imbue hope into thousands seeking freedom.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now