“The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers.”

So says the U.S. Constitution in Article 1, Section 2. It says nothing about the Speaker’s duties. There is not a word about qualifications for the office. The Speaker doesn’t have to be a member of the House, or even an American. The members of the House are free to elect anyone of any age, gender, origin, or residence to the post.

The Founding Fathers didn’t specify further because they already had a clear example in mind: Britain’s Speaker of the House of Commons. Originally created in the 1200s, the Speaker was an agent of the king who presided over the members of the Commons. By the 1600s, though, the Speaker was dissociated from the Crown. He was now expected to be independent and nonpartisan. He was only meant to supervise the proceeding, and was prevented by House of Commons law to “sway the House with argument or dispute.”

This was the model the Founders would have wanted to replicate: a dignified, nonpartisan, parliamentarian leader.

Such a Speaker could have been found in those days before the political parties had formed. The early Speakers were treated with deference, paid twice the salary of congressional members, and given special housing accommodations. They were, after all, second in succession to the president after the vice president.

For a time, Speakers served as disinterested managers of the House. But by the late 1790s, America’s political parties had emerged, and House Speakers found they were in a unique position to promote their party’s agenda.

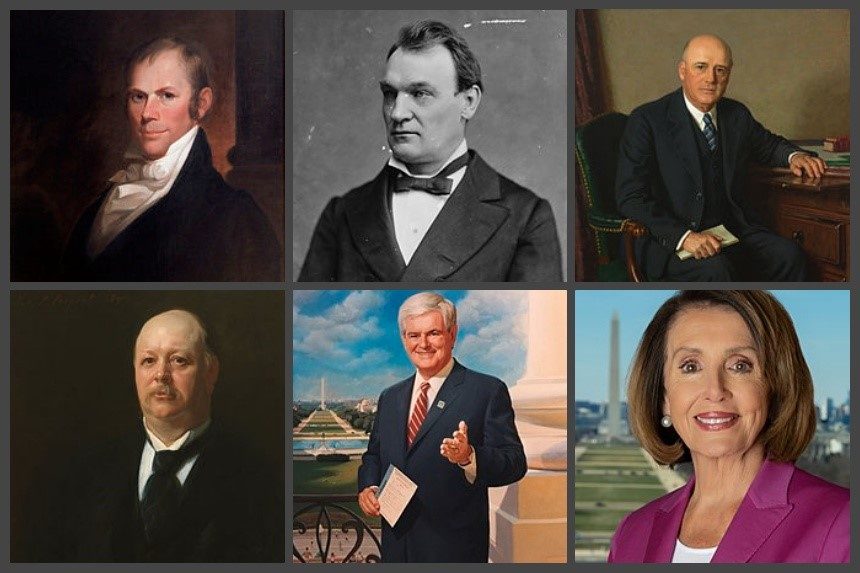

One of the earliest Speakers who realized the power of the office was Henry Clay, who held the office six times between 1811 and 1825. He shaped pending laws by carefully choosing the people who would sit on congressional committees, and he found ways to limit debate. In 1812, he pushed a declaration of war against Great Britain through the House. He also forced official recognition of the new Latin American republics emerging from under Spanish rule.

In the 1880s, John G. Carlisle of Kentucky increased the Speaker’s power to control the House’s agenda by establishing a system for recognizing members. Under House Rule XVII, members could only address the Speaker, who decided who spoke and on which matter of business. Members could only gain this permission from the Speaker, allowing him to give floor time to members whose bills he wished to advance.

Thomas Brackett Reed dramatically expanded the Speaker’s power between 1895 and 1899. He exercised so much control over the House agenda he was referred to as “Czar Reed.” Dismissing any regard for bipartisanship, he believed the majority party in the House should run everything. The best arrangement for the House, he said, was “to have one party govern and the other party watch.”

Until Reed held the office, the minority party could halt House business if enough of its members refused to answer a quorum call. Even if they were present in the chamber at the time of the call, they were technically absent if they didn’t respond to their name being called. Reed overcame this obstacle during one vote by simply counting all congressional members as present even if they hadn’t answered. Members of the minority party protested, but Reed said the fact that he was even debating the question with them meant they were in the chamber.

“The right of the minority,” he said, “is to draw its salaries and its function is to make a quorum.”

In 1910, Speaker Joe Cannon had taken control over so many House activities that even members of his own party rebelled. Cannon had used his control of the House to block progressive legislation and would depose the heads of congressional committees who disagreed with him. His direct influence over the Rules Committee determined which laws would be sent to the floor for a vote.

On St. Patrick’s Day of that year, while Cannon was out celebrating with party cohorts, progressive Republicans, working with opposition members, revised the House rules and returned control to the proper committees and lower-level party leaders.

In the years following Cannon’s downfall, legislative power shifted back to the chairs of House committees. Speakers Champ Clark of Missouri and Frederick Gillett of Massachusetts took far less dominant roles than their predecessors.

Between 1940 and 1961, though, Sam Rayburn of Texas proved an effective Speaker who could get bills passed, not on the power of his office, but on the strength of his character and his ability to persuade.

By the 1970s, much of the House’s power was held by chairs of congressional committees. It was at this point that legislative power began shifting back to the Speaker. A succession of Speakers between 1977 and 1995 expanded the role. In 1975, Speaker Carl Albert reversed some of the reforms of 1910 by gaining the power to appoint a majority of the members of the Committee on Rules. Previously, the Committee — which determines which bills will be presented to the House — had been semi-independent. Now it was again an instrument of the majority party.

In 1994, the legislative power of the House Speaker came back full circle to the days of Speaker Reed when Newt Gingrich was given the office. He openly exercised power in the interest of his party and took partisan politics to a new level. He encouraged party members to be “nasty” and stop being “nice.” He said his goal was “to do nothing less than reshape the federal government along with the political culture of the nation.”

Thomas Mann, a congressional scholar at the Brookings Institution, told The Atlantic that, until the ’90s, House members still believed in genuine deliberation and compromise. But under the new Speaker, “it went from legislating, to the weaponization of legislating, to the permanent campaign, to the permanent war.”

In the coming weeks, a new Speaker will be elected. Their job will be to handle the business and proceedings of the House. They will refer bills to committee, decide on points of order, and declare recesses. They will grant members of the House the right to address the assembly. They’ll also enforce House rules and put questions on the floor to a vote.

But they will still be the political leader of House’s majority party, with the power to further their party’s agenda.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now