This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Last week, the DeSantis administration finally released the full text of their proposed state law that would overhaul Florida’s public higher education system. That bill, Florida HB 999, pulls together many elements we’ve already seen playing out in Florida and around the country: banning campus diversity initiatives and making it impossible for institutions to receive grants related to diversity; turning both core curricula and institutional mission statements over to politically appointed Boards of Trustees; and eliminating core academic practices like tenure and faculty hiring committees. But it features many other troubling details as well, and one of them is quite specific: HB 999 would ban gender studies majors and minors on all Florida campuses.

That detail reflects the widespread contemporary belief that gender studies is part of the system of indoctrination through which educators are seeking to fundamentally change American children and society for the worse. But as we begin Women’s History Month, it’s worth emphasizing how much the opposite is true: women history, and especially women’s activism for rights and equality, has shaped America for the better throughout our history. The first National Women’s Rights Convention offers an excellent case study of those multilayered influences and legacies.

The July 1848 convention in Seneca Falls, New York, is often highlighted as the start of a national women’s rights movement; it was indeed important, and out of it came the crucial “Declaration of Sentiments” that helped guide the movement.

But it was a gathering two years later, the October 1850 convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, that billed itself as the “First National Women’s Rights Convention,” drawing more than 900 attendees (triple the 1848 numbers) and truly launching a nationwide movement. Highlighting a handful of the Worcester convention’s impressive and inspiring women highlights the connections of women’s activism and history to every part of American society.

The convention’s organizer and President-elect was Paulina Kellogg Wright Davis, a longtime activist whose opening address noted the importance of applying the 1848 “Declaration of Sentiments” to “those conditions of the times which the reformer seeks to influence.” Yet she made clear that “the reformation which we propose … is radical and universal.” By this time, Davis had been seeking such reformations for decades through her work as an abolitionist, including organizing an 1835 anti-slavery convention in Utica, New York with her first husband, Frances Wright. After Wright’s death she continued to pursue those goals and to link them with women’s rights activism, not only at the Worcester convention but also in Washington, D.C. alongside her second husband, Rhode Island Congressman Thomas Davis. And for the final quarter-century of her life, she dedicated much of her work to advocating for women’s health and medical needs and rights, including a speaking tour that urged women to study medicine and become doctors.

The local organizer who called the convention to order, Sarah H. Earle, further illustrates the connections of women’s rights to abolitionism. Earle had moved to Worcester from her native Nantucket in 1821 at the age of 22, and over the next three decades she became a key player in the city’s abolitionist community, founding the Worcester Ladies Anti-Slavery Sewing Circle and the Worcester City Anti-Slavery Society and providing a home and family for two orphaned African American girls, Catherine and Cynthia Gardner. Three years after the Worcester convention, Earle co-founded (with Paulina Davis and others) and personally funded The Una, the first periodical in America to be owned, published, edited, and written entirely by women. And throughout these years she fought for women’s political and legal equality in her home state, authoring an 1851 petition to the State Legislature in support of women’s suffrage and an 1855 one to remove the word “males” from the Massachusetts Constitution.

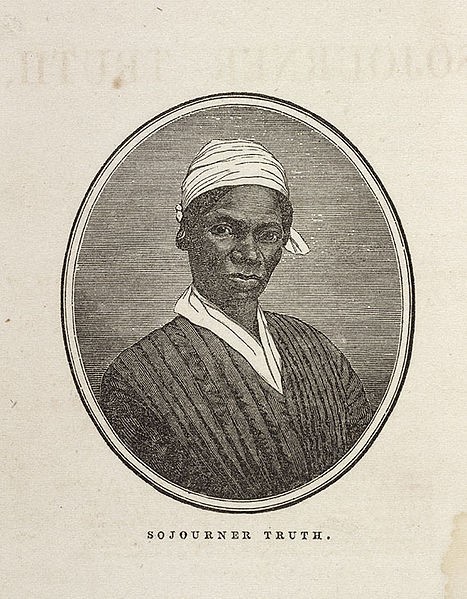

Local figures like Earle were joined at the Worcester convention by attendees from around the country, none of whom were more striking and important than Sojourner Truth, the formerly enslaved person turned abolitionist and women’s rights activist (although her fellow Worcester convention attendee Frederick Douglass certainly rivaled Truth in impressiveness). It was at another national women’s rights convention a year later — the May 1851 convention in Akron, Ohio — that Truth would first deliver her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. She likewise spoke eloquently at the Worcester convention, and her speech on the need to fight for enslaved women led to a resolution in which the attendees unanimously expressed solidarity with “the trampled women of the plantation.”

Finally, the Worcester convention also had a crucial impact on the blossoming British women’s rights movement. Following the convention closely from across the pond was the pioneering English social scientist and reformer Harriet Martineau, who had befriended Paulina Davis upon her first visit to the U.S. in the 1830s (after which Martineau authored her book Society in America [1837]). In a letter she wrote to Davis in August 1851, Martineau thanked Davis for passing along the convention’s full transcripts and remarked, “I hope you are aware of the interest excited in this country by that Convention, the strongest proof of which is the appearance of an article on the subject in the Westminster Review…I am not without hope that this article will materially strengthen your hands, and I am sure it can not but cheer your hearts.” And indeed, the Sheffield Female Political Association, considered the U.K.’s first women’s suffrage organization, was founded in early 1851 after its organizers read about the Worcester convention in the New York Tribune for Europe newspaper.

Women’s history and gender studies are not niche topics nor hotbeds of “woke” controversy. They are quite simply fundamental parts of every layer of American society, community, and history. The 1850 Worcester Women’s Rights Convention and its impressive organizers and attendees offer one particular window into that vital role.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now