Everyone knows that in school, doing great on a math exam will not (or should not, at least) affect one’s grade in history or drama. And yet, it is common for people to assume that a water test covers everything bad that could be in the water. Not so. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, “About 1 in 8 American residents get their drinking water from a private well. And about 1 in 5 sampled private wells were found to be contaminated at levels that could affect health.” Yikes.

Most health departments advise that wells be tested once a year for fecal coliform bacteria, the presence of which indicates the well may have been impacted by septic leakage or manure runoff. But this test won’t tell you if residues from agricultural chemicals, spilled gas or oil, or other chemicals are getting in your water. Those are very different tests.

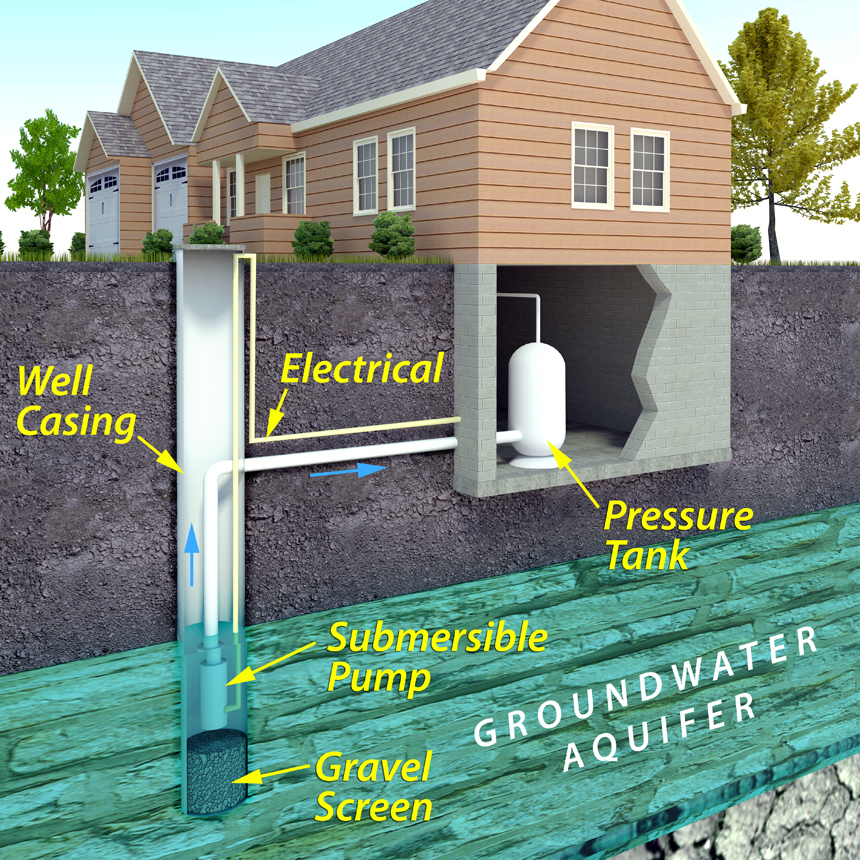

While no well is pollution-proof, a dug well is more at risk for pollution from surface runoff. A drilled well is more secure, but regardless how deep it is, it’s still vulnerable to contamination. I’ve heard people say their well was drilled into “solid rock.” If that was true, they’d have a dry hole in the ground. Water flows into well boreholes at various depths through bedding planes, joints, and fissures. Contaminants can sometimes be drawn into a well along those same channels.

Broadly speaking, there are three categories of water quality measurements: Biological, inorganic, and organic. In terms of biological, the most common indicator of potential disease pathogens in the water is the presence of coliform bacteria. Some are harmless and occur naturally in soil, but fecal coliforms live exclusively in the gut of warm-blooded animals. The presence of fecal coliform bacteria could be from a septic system or from animal manure.

Inorganic contaminants include lead, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, and copper. Nitrates from fertilizers can sicken or even kill infants, and its presence suggests that other agricultural chemicals also might be getting into the water. Older pesticides used lead, arsenic, and copper, which are heavy metals that do not break down. Cadmium and chromium are released from distant smelting operations, and also when colored paper is burned. These can all leach into groundwater.

Naturally occurring inorganics in water such as calcium or magnesium (which causes water to be “hard”), iron, chloride, and sulfur can leave deposits and stains, and cause objectionable smells or tastes, so you’ll know if your water is high in minerals. Lab testing for inorganics usually costs between $30 and $50 per element. A simple, inexpensive reverse-osmosis under-sink unit will remove most inorganics.

“Organic” is a misleading term, because while eating organic food is good, consuming organic chemicals is definitely not. Pesticides, degreasers, gasoline, oil, antifreeze, and many paints are all organic chemicals. How do organic pollutants get into our water? It’s shockingly easy, especially in the Northeast where it rains a lot and the water table is relatively shallow. Leaky fuel tanks, floor drains, septic systems, and even surface spills can contaminate wells.

We’ve heard oil and water don’t mix, but that’s not entirely true: they don’t mix much, but more than enough to pollute water. Benzene, a constituent of gas and diesel, is 0.018 percent water-soluble, which doesn’t sound bad. However, it equals 180,000 parts per billion (ppb), far above the maximum of 5.0 ppb of benzene in drinking water set by the US EPA. The odor threshold for benzene is 50-100 ppb, so one could unknowingly drink it above the recommended upper limit.

It’s quite common for people to let things like paint thinner go down the drain. Trouble is, these chemicals can enter groundwater through septic leach fields and find their way into wells. Petrochemicals spilled in your garden could degrade in one season if you added manure and tilled often, but underground, they break down slowly over decades. Because groundwater is always flowing (slowly except in karst regions), contamination from an off-site spill can show up years later.

Testing for organics can be complex. Petroleum and solvents are covered by a single test, usually either EPA Method 524.2 or 503.1. The lab you choose may have other recommendations, too. Pesticides often have specific tests for each chemical “family.” The cost of testing for petroleum residues and solvents varies, typically in the $80-$150 range. For pesticides, it can be higher.

But homeowners should not assume their water is tainted. One would only suspect petroleum contamination if water has a chemical odor, or if a gas station, auto repair shop, dry cleaner, or other industry is nearby. When paint solvents flushed down the drain show up in wells, they are nearly always at very low concentrations that can be removed by inexpensive carbon filters.

In the rare cases of high petroleum levels in water, the local Health Department and state environmental protection agency should be notified, as they will advocate for homeowners in these situations. Owners are almost never on the hook for the high cost of whole-house filtration systems, which involve big activated-carbon tanks in series with sample ports in between. State regulators can force the responsible party (an oil company, for example), to pay, and insurance may cover all or most of the cost.

The take-home message is that what goes down – into the soil or down the drain – can come up to our kitchen sink. Let’s work together to keep our well, and those of our neighbors, well.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now