Senior managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

The German word Schadenfreude is often at the top of online lists (unless they’re alphabetical) of supposed “foreign words that are untranslatable in English.” The writers then go on to translate the word — “the joy felt at the suffering of others.”

But if it’s so untranslatable, how did they translate it so easily?

What they mean, of course, is that English does not have one lone word that means the same as Schadenfreude. So we just use the German word (though lowercased), just like nachos, vodka, and karaoke.

But in the case of schadenfreude (from the German words schaden “damage, harm” and freude “joy”), it isn’t 100 percent true that there isn’t a single English equivalent.

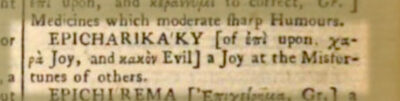

Nathaniel Bailey’s dictionary of 1751 includes the word epicharikaky (with emphasis on the “ick” — seriously). English spelling has evolved quite a bit in the almost 275 years since; in modern times, this word would be epicaricacy. For either spelling, the word comes from Greek roots: epi- “upon” + chara “joy” + kakon “evil,” literally “joy upon [witnessing] evil.”

Why didn’t this word catch on? Frankly, there isn’t much evidence that the word ever got much use in the first place, and it doesn’t appear in many dictionaries, then or now. Besides Bailey’s dictionary, it also appears in John Ash’s dictionary of 1775, though he likely lifted it from Bailey. Until the internet age, you couldn’t find it in very many other places; it was even left out of the Oxford English Dictionary.

To understand why this was the case, we have to go back to the 15th and 16th centuries. During this time, English was a smaller language, lacking words for many objects and concepts that existed in other languages. English was also considered low-class, even rude, so that many a writer, poet, and politician — though they be English themselves — avoided using that language when they could. Instead, these word nerds reached into their knowledge of Latin and Greek roots and kludged together new words — neologisms — to fill the gap.

It was kind of a craze among many logophiles. The new words were often long, hard to pronounce, and difficult to figure out. They were often referred to as inkhorn terms or inkhornisms — playing on the idea that early ink holders were made from animal horn, and writing out these neologisms required more ink and would empty the inkhorn faster.

Many of these inkhorn terms sound ridiculous today — for example, quinquipunctual for “having five points” (like a sheriff’s star), or exsufflicate for “frivolous.” Many others have stuck around and seem quite natural, though: celebrate, encyclopedia, and ingenious were all inkhorn terms.

Many early monolingual English dictionaries, in the 16th and 17th centuries, were created primarily to explain (and sometimes complain about) these new and often technical inkhorn terms. When Nathaniel Bailey was compiling his dictionary in the 18th century, he was looking at the words in previous publications, like any good lexicographer would, including these earlier dictionaries full of inkhorn terms. That explains why Bailey’s dictionary also includes, alongside epicharikaky, entries like hoggasius “a sheep in its second year,” lampadias “a blazing star resembling a torch,” and rixilation “scolding or brawling” — words that might not have gotten much use in the 18th century but were so forgotten by the 20th that they were left out of unabridged dictionaries.

You won’t find epicaricacy in any modern, general-use dictionary. Its continued existence is solely attributable to its inclusion in lists of long, interesting, or obsolete words. That is, unless we English speakers begin to use it on a larger scale. If we can make the word common and frequent enough, the folks at Merriam-Webster et al. will have to consider adding it to their dictionaries.

I’ll give it a shot, but I don’t hold much hope of actually replacing schadenfreude. Feel free to laugh at my failure.

Thanks to fellow logophile Stan Carey for pointing me in the direction of this word.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now