This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As we near Veterans Day, it might seem that the United States’ military budgets are robust. Yet support for our veterans, like advocacy for the well-being of active-duty servicemen and women, doesn’t necessarily line up with either military institutions or wars. Indeed, one of the most decorated military figures in American history, Major General Smedley Butler (1881-1940), dedicated his final decade of life to making the case that supporting veterans and active-duty servicemen and women required opposing both wars and the military-industrial complex that wages and profits from them.

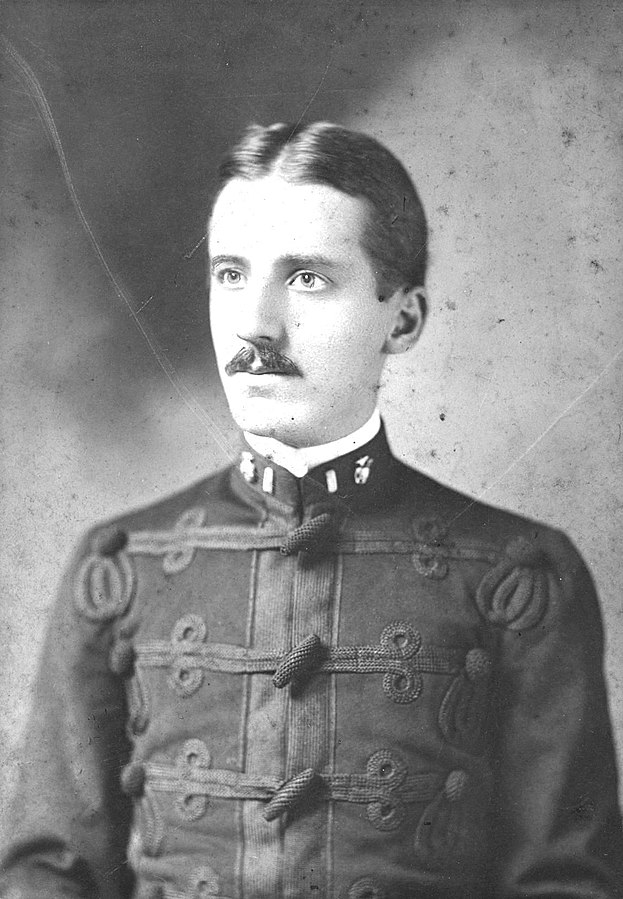

The son of a prominent West Chester, Pennsylvania family, Smedley Butler dropped out of the prestigious Haverford School before he turned 17 in order to enlist in the Marine Corps (having lied about his age to receive a commission as Second Lieutenant) and fight in the Spanish American War. For the next two decades Butler served with distinction in every American military conflict in the period, including the Philippine American War; the alliance with China to suppress the Boxer Rebellion; Central American occupations of Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico, and Haiti; and his culminating wartime service as Brigadier General supervising a debarkation depot in France during World War I. Across these countless, complex conflicts Butler remained committed to supporting and leading his fellow servicemen, and for those efforts he received 16 medals, five for direct heroism in combat. By his career’s end he had become the only Marine to be recognized with two Medals of Honor and Marine Corps Brevet Medal.

For the decade after that World War I service Butler moved into the kinds of military and civil leadership roles that would be expected of a prominent General, first becoming the commanding officer at the Marine Corps base in Quantico and then serving for two years as President Calvin Coolidge’s personal choice to serve as Philadelphia’s director of public safety. From 1927 to 1929 he led a Marine expeditionary force to China, representing not only the military but also the U.S. federal government in its diplomatic dealings with that nation. Butler was known throughout this time as an outspoken figure, the “Maverick Marine” who was not afraid to air controversial perspectives. Yet Butler seemed to remain a prototypical military officer, an embodiment of the armed forces in their multiple domestic and international roles.

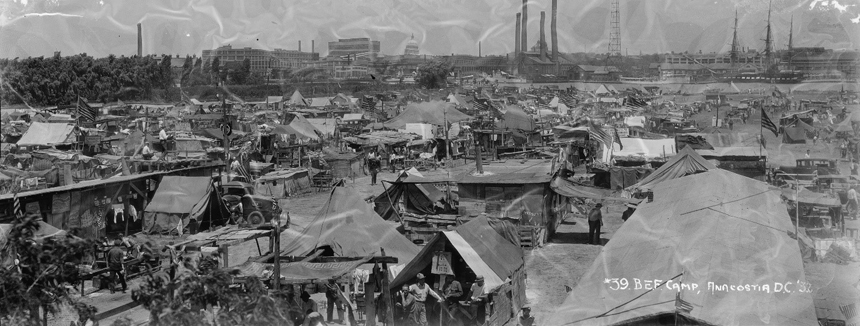

It was Butler’s striking connection to two distinct 1930s events that changed his perspective about the military. In the summer of 1932, with the Great Depression deepening, World War I veterans from around the country marched to Washington, D.C. to protest a lack of promised compensation for their service. Calling themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, or the Bonus Army for short, these tens of thousands of protesting veterans set up a “Hooverville” camp in the city’s Anacostia Flats area in mid-June. The federal government feared them (opening FBI files on most of the protesters) and the national press was unsure at best, but Smedley Butler became a consistent and vocal ally. On July 18th he and his son toured the camp and spent the night there, and the next day he gave a fiery speech to the veterans, arguing that “I never saw such fine Americanism as is exhibited by you people.” When the Hoover administration used the army (led by General Douglas MacArthur) to burn down the camp and expel the protesters, Butler called himself a “Hoover-for-Ex-President-Republican.”

While his experiences with the Bonus Army convinced Butler that the government and military did not truly support veterans, it was his connection to the 1933 “Business Plot” that sought to overthrow President Roosevelt that likewise radicalized Butler against the nation’s corporate and military-industrial forces. As I highlighted in this Considering History column on the plot, Butler testified before the House of Representatives Special Committee on Un-American Activities that the plot’s leaders had approached him to help lead the coup; covering the committee’s February 1935 report, Time magazine noted that “a two-month investigation had convinced the committee that General Butler’s story of a Fascist march on Washington was alarmingly true.”

These 1932 and 1933 experiences turned Butler into a vocal and impassioned anti-war activist and critic of the military. Beginning in December 1933 he toured the nation in an effort to “educate the soldiers out of the sucker class,” delivering speeches like “You Got To Get Mad” in which he noted that “Peace times they suffer and in war times they bleed.” He concluded, “The only trouble with you veterans is that you still believe in Santa Claus. It’s time you woke up — it’s time you realized there’s another war on. It’s your war this time. Now get in there and fight.” Butler did his part to help lead that fight, serving from 1935 to 1937 as a spokesperson for the American League Against War and Fascism.

Butler expressed his anti-war and -corporate arguments most potently in his 1935 book War is a Racket. He writes there, “I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer; a gangster for capitalism….Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents.”

This Veterans Day, with both the military-industrial complex and the crisis of veteran suicides growing ever larger, we would do well to listen to the voice of this decorated, dedicated, and disapproving Marine.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now