This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

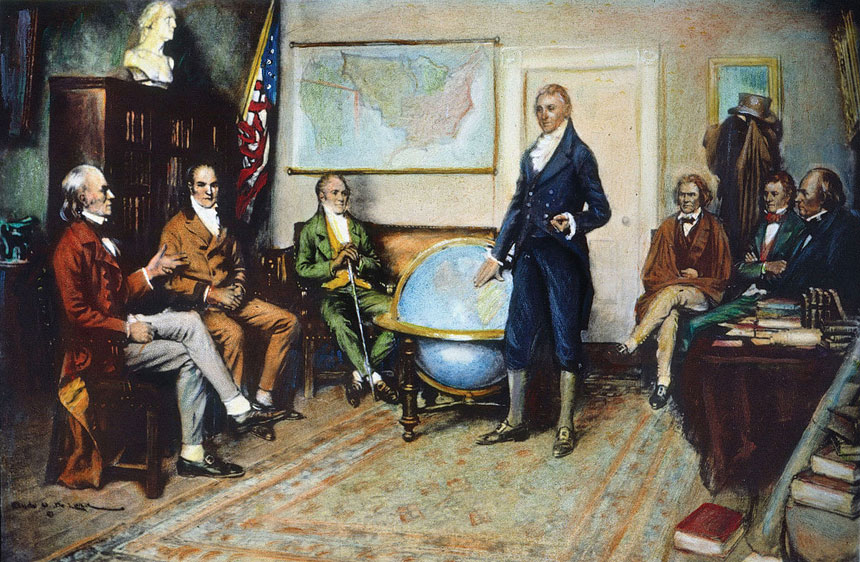

Two hundred years ago this week, during his annual State of the Union Address to Congress on December 2, 1823, President James Monroe first articulated the foreign policy arguments that would come to be known as the Monroe Doctrine. Largely conceptualized and written by Secretary of State (and next President) John Quincy Adams, the Doctrine was ostensibly a demand that European powers stay out of the affairs of the many newly independent Western Hemisphere nations. But it very fully framed that question as one centered on U.S. interests, and thus imagined a hemisphere dominated by the United States.

That idea, of the U.S. as a dominant power throughout the Western Hemisphere, has directly contributed to visions of U.S. influence on and interference with other nations over the two centuries since the Monroe Doctrine’s debut; one example is Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger’s role in the 1973 Chilean coup about which I wrote in this Considering History column. It has also led to Latin American imitators of the most extreme kinds of U.S. leadership, as we’ve seen in the last few weeks with the election of the Trump-inspired far-right candidate Javier Milei as President of Argentina.

Yet these are not the only ways to view a U.S. relationship to the rest of the Western Hemisphere. In the late 20th century, the French Martiniquais poet and scholar Édouard Glissant offered a very different vision in his groundbreaking essay “Creolization in the Making of the Americas” (1995). Glissant saw every nation in the hemisphere, including the United States, as connected through shared cultural exchanges and experiences, combinations of communities and identities he termed “creolization.” His essay closed with a hope that this “extraordinary complexity of the exchange between cultures…may yet forge future Americas that are at last and for the first time both deeply unified and truly diversified.”

There are moments in American history that offer a counterpoint to the Monroe Doctrine and lean into Glissant’s vision of the U.S. as interconnected with the rest of the hemisphere. One moment that linked the U.S. to its fellow nations in a more genuine community of peers was the creation of the Organization of American States in 1948. But to understand how the OAS was created across a century-and-a-half of diplomacy and debate, we need to better remember the figures who have made the case for the U.S. as a partner to its hemispheric neighbors.

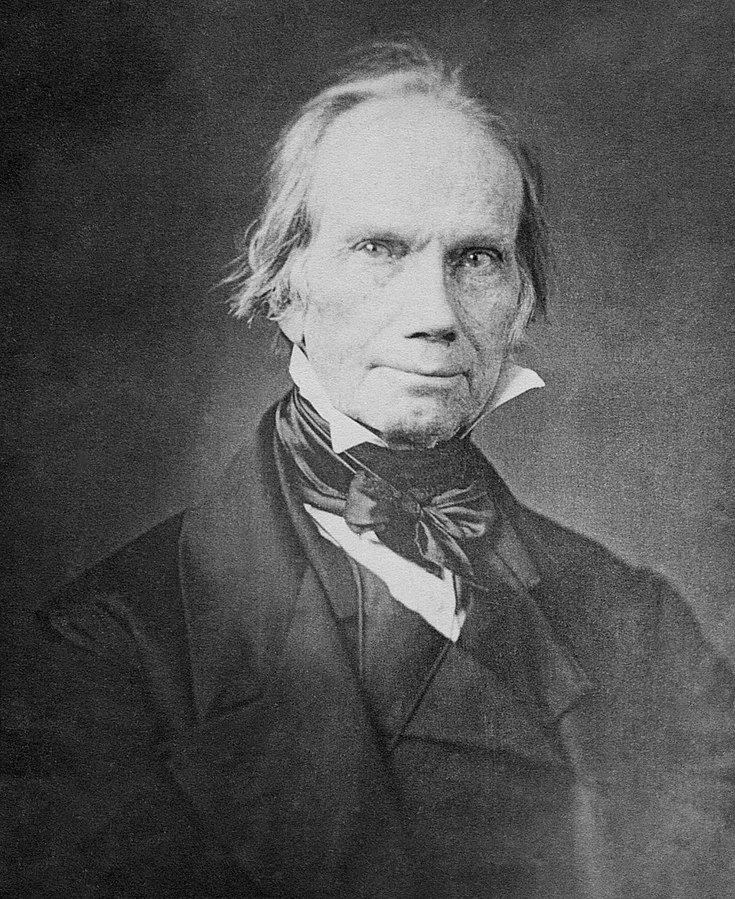

One of the earliest and most impassioned voices for that hemispheric community was a peer and ally of James Monroe and John Quincy Adams: Kentucky Congressman and Speaker of the House Henry Clay. In two famous March 1818 speeches on the House floor, Clay made the case for full U.S. recognition of and support for Latin American nations in their fights for independence from Spain, and he continued to make that case both publicly and privately to Monroe and Adams in subsequent years. Clay was certainly an influence on that element of the Monroe Doctrine, and brought a sense of hemispheric solidarity to his role as secretary of state during the Adams administration. As a 1927 Senate report on plans to erect a statue of Clay in Caracas, Venezuela, put it, “in the minds of the Latin American countries, it may be said that Henry Clay is regarded as a figure of the Western Hemisphere rather than of the North American Continent.”

While serving as Adams’s secretary of state, Clay was also intimately involved in the first official effort to connect the U.S. to its Latin American neighbors. In the summer of 1826, Venezuelan revolutionary and leader Simón Bolivar organized the Congress of Panama, gathering representatives of numerous nations in Panama City with the goal of creating a league of American republics. Adams and Clay were eager for the U.S. to be part of the Congress and pushed Bolivar to extend a formal invitation, which he did. However, the U.S. delegation was delayed in departing for Panama as many southern states expressed concerns over partnering with nations that had outlawed slavery, as many of the new Latin American countries had. As a result, one of the two delegates, Congressman John Sergeant, arrived after the Congress had concluded; the other, Ambassador to Colombia Richard Clough Anderson Jr., tragically died en route. But the connection of the U.S. to this hemispheric gathering was an important step nonetheless.

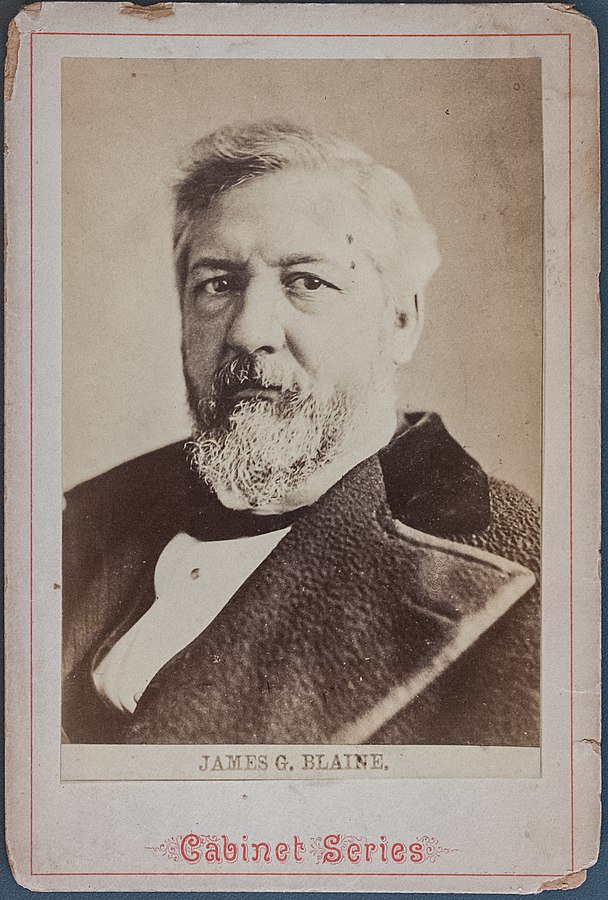

Bolivar’s imagined hemispheric league did not come to pass in the 1820s, but 50 years later another political figure to build on that prior connection. In 1881 James Blaine, also a former speaker of the House turned secretary of state and one who was directly inspired by Clay’s hemispheric vision, invited representatives from every Western Hemisphere nation to come to Washington for a Pan-American conference. When President Garfield was assassinated later that year Blaine was replaced and the conference stalled; but in 1889 newly elected President Benjamin Harrison appointed Blaine secretary of state once more. This time Blaine was able to bring his plans to fruition, holding the First International Conference of American States in Washington between October 1889 and April 1890. Although the gathering did not produce substantive policies, it did conclude with the April 14 creation of the International Bureau of American Republics, an influential organization and the reason why that day is now celebrated as “Pan American Day.”

Over the next half-century, there were eight more such gatherings. Each of them represented an important step in this growing community, but it was the Ninth International Conference of American States, held in Bogotá between March and May 1948, that truly created an even greater level of hemispheric connection and cooperation. Inspired by the post-World War II Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (1947), and led by U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall, the 21 nations at the Ninth Conference signed the Charter for the Organization of American States (OAS). Adopting the principles of the human rights manifesto known as the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, the OAS embodied an idealized vision of what this kind of hemispheric community could be and fight for.

Far too often in the 75 years since the OAS’s founding, the U.S. and other countries in the Western Hemisphere have failed to live up to that vision. But it remains part of our history. We can still be inspired by the hemispheric visions of Glissant, Clay, Bolivar, Blaine, and many more.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now