As a longtime gardener who likes to make healthy and eye-pleasing meals, I enjoy the colorful veggies that have come on the market in the past decade or so. If you have space on a balcony or patio for a few containers, you can now grow red lettuce, orange cauliflower, pink potatoes, golden beets, black tomatoes, and purple carrots. These and other rainbow-hued produce are also available at farmers’ markets in season, and in large grocery stores.

But as Doctor Seuss noted in Green Eggs and Ham, pigmented foods need the right context or people are likely to balk. While bright colors are charming in a stir-fry or omelette, purple milk and orange meatloaf don’t have the same appeal. Green beans, peas, and broccoli are good, whereas Soylent Green should not be on anyone’s menu.

Aside from blueberries, blue foods are a tough sell for me. Only chicken cordon bleu with a glass of Blue Nun sound enticing, and neither of those is actually blue. In particular, I find the phrase “blue fungus” to be an appetite suppressant. And yet, an edible blue mushroom called Lactarius indigo may provide us with a powerful means of battling the climate crisis, as well as helping to alleviate food insecurity.

Also known as the indigo milk cap or blue milk mushroom, L. indigo is native to forested regions of eastern North America, East Asia, Central America, and parts of Western Europe. This mushroom’s most unusual feature is that when cut or broken, it oozes a milky blue latex. Once exposed to the air, its gooey blue “blood” slowly turns green. All of which screams “yum,” of course.

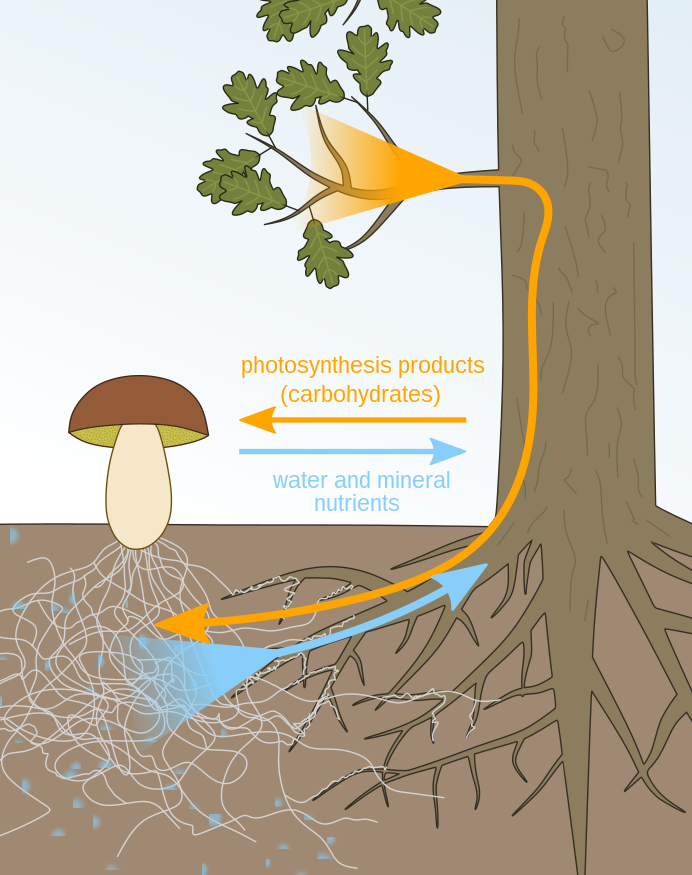

The indigo milk cap is one of many species of mycorrhizal fungi that form symbiotic relationships with tree roots. Though mycorrhizae take small amounts of sugars from roots, they greatly boost their efficiency, allowing trees to absorb water and nutrients more readily. In this win-win scenario, L. indigo lives off trees while making them healthier and faster-growing overall.

Eaten fresh, indigo milk caps are said to have the crispness of an apple. Their flavor varies from site to site, but is usually described as mild, and when cooked tastes similar to a portobello. Indigo milk caps and other mushrooms can also be processed to mimic seafood, meat, and cheese products, as well as used to make soy sauce, or even fermented into wine and beer.

No other mushroom bleeds blue, but always check with an expert before eating any wild-sourced mushroom. There are a number of well-respected online resources to help identify and source L. indigo, and even some recipes for preparing them.

In a study published in February 2022, researchers from the University of Stirling in England, and El Colegio de la Frontera Sur San Cristóbal de las Casas in Chiapas, Mexico, showed that the amount of protein found in blue milk mushrooms on an acre of forest exceeds that of beef cattle raised on an acre of pasture. Not only that, the mushrooms can be harvested year after year with no inputs, unlike beef production, where animals must be tended and watered daily, with periodic fence replacement, veterinary care, predator control, and other expenses.

However, the real significance of these mushrooms is that forests can be left to grow for centuries. As these “shroom-forests” age and continue to sequester carbon, they help to mitigate climate change, and all the while can still be used for things like recreation or hunting. Land managers can keep harvesting a percentage of mature trees on the same prudent schedule as before, without compromising forest health or affecting the L. indigo mushroom crop. Right now, forests are being clear-cut at the alarming rate of about 24.7 million acres a year. In South America, around 85 percent of deforestation is to create pasture for beef cattle and to grow other kinds of animal feeds. Worldwide, beef cattle burp enough methane each year to equal over 3 billion tons of carbon dioxide, on top of the many other types of greenhouse-gas emissions caused by deforestation, such as faster C02 release from warmer soils, and diesel exhaust from road-building and timber-harvesting equipment.

Harvesting blue milk mushrooms on a portion of the woodlands now slated for conversion to beef pasture and planting new forests with trees inoculated with L. indigo are great ideas, but will require buy-in from landowners, and most likely some kind of government incentives as well.

Public buy-in for foods based on L. indigo will also be crucial. In 1960, Dr. Seuss got his character to accept green eggs and ham by pestering them with an intrusive stalker. These days, such antics would get Sam-I-Am taken away in handcuffs. But with soaring food prices giving everyone the “food blues,” perhaps a clever PR campaign can sell the world blue burgers and cheese.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now