With the elections approaching, our screens and billboards are filled with political ads trying to persuade voters to support a candidate or a cause. This form of campaigning is certainly not new, and while its main goal is to stir people into active engagement, the result is often turning politics into a consumer product.

If today it’s the candidates who are being sold, in the 1920s, companies found that politics and elections themselves could be a useful marketing tactic to sell their products.

Advertising companies have long targeted “Mrs. Consumer” in their campaigns, seeing women, and particularly housewives, as the main audience for their ads. While early ads often portrayed the woman consumer as passive, emotional, and gullible, by the 1920s — as women became more active and visible in the public sphere — ads also changed their approach. Looking to capitalize on women’s new sense of citizenship leading up to and after the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, ad campaigns sought to convince women to exercise their political power not only at the ballot box but also in the store.

Even before the 19th Amendment, retailers and manufacturers were eager to cash in on women’s new sense of political agency by framing consumption as the manifestation of their rights. “Another Victory for Equal Rights!” an ad for The Royal Tailors company announced in 1914, proclaiming that they had begun to provide services for both men and women. Another 1914 ad for Kellogg’s Corn Flakes also adopted the suffrage slogan “Votes for Women,” featuring a march of little girls as if in a suffrage parade, claiming that “the women of this country have always voted ‘aye’” for the cereal.

The increasing numbers of women working in the advertising business also helped in shifting views on the woman consumer. Frances Maule — a veteran suffragist that made a career as an executive copywriter at J. Walter Thompson Advertising Company — argued in a Printers’ Ink article that “[w]hen we sit down…to try to visualize the woman purchaser, we should do well to recall to our minds the fact — so well expressed in the old suffrage slogan — that ‘Women Are People.’” Maule rejected the “good old conventional ‘angel-idiot’ conception of women,” and instead suggested to see women as a more complex group of types and interests.

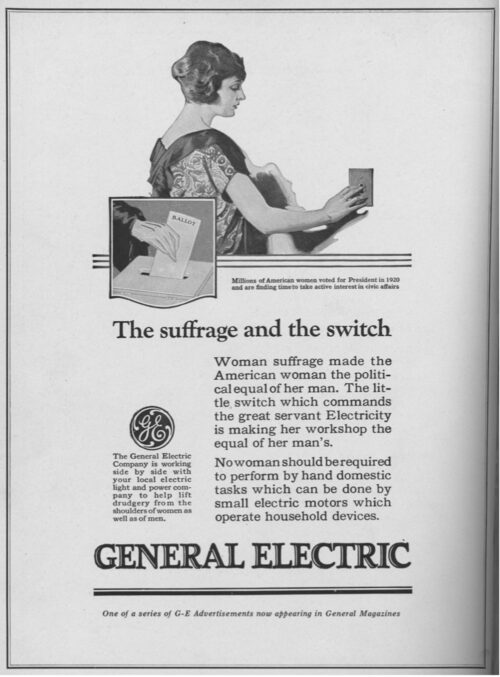

Once the 19th Amendment had passed, advertisers grew even bolder in connecting voting with consumption. A 1923 General Electric ad titled “The Suffrage and the Switch” conflated the achievement of women’s suffrage with the progress that electricity brought to domestic life. Portraying a fashionable woman turning an electrical switch next to a smaller picture of a woman’s hand casting a ballot, the copy announced that “Woman suffrage made the American woman the political equal of her man. The little switch which commands the great servant Electricity is making her workshop the equal of her man’s.”

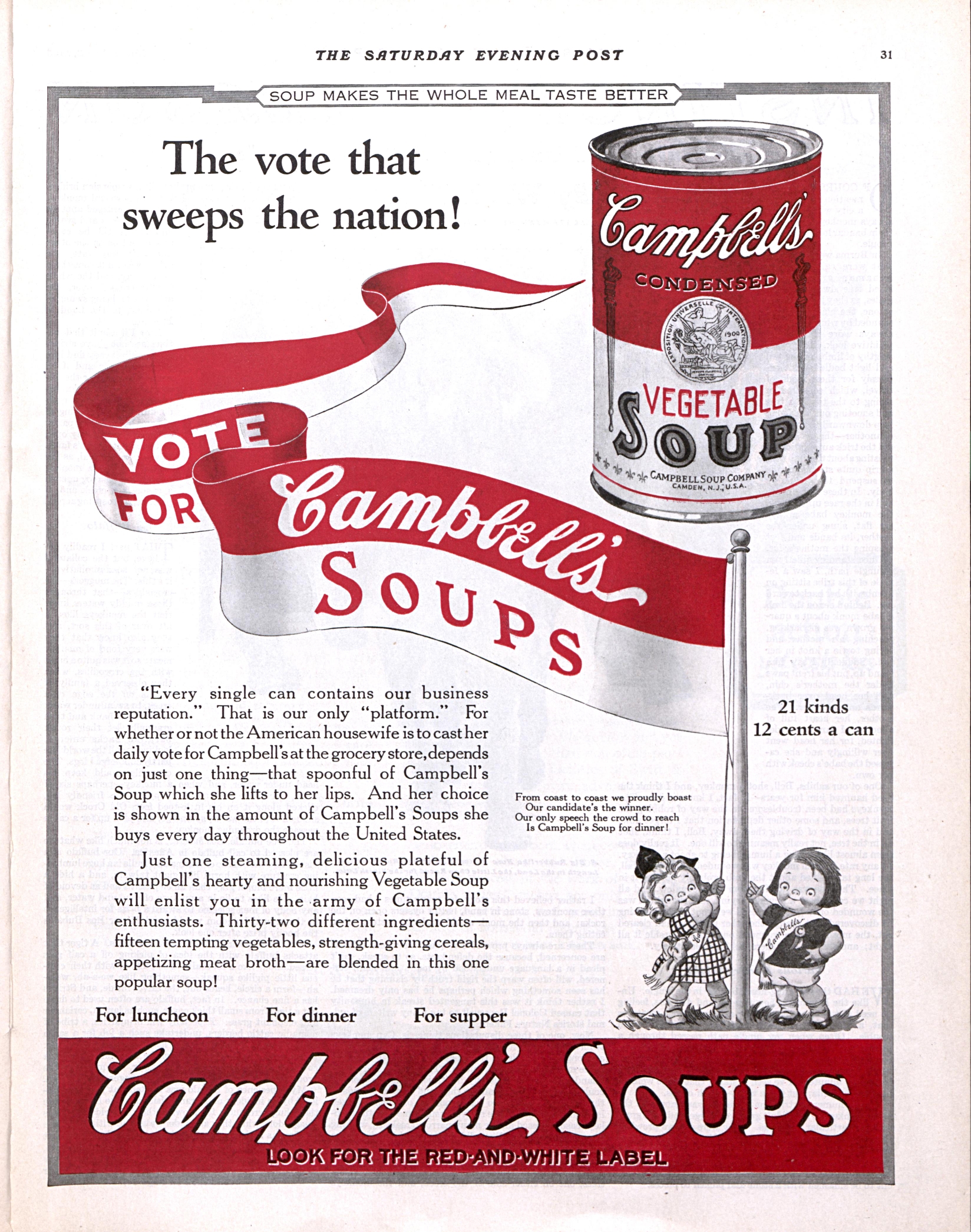

While campaigns by the League of Women Voters sought to educate women on the intricacies of the political process and how to cast their vote properly, advertising consultant Christine Frederick reminded companies that “the polls [are] being open every day at a million or more retail stores.” As a 1923 ad for Campbell’s Soup proclaimed, the American housewife “cast her daily vote for Campbell’s at the grocery store,” making her impact felt where it counts.

The emphasis on consumption as a form of political participation came to dominate ad campaigns in the 1920s and 1930s, suggesting that women’s “voting power” might count more in the marketplace than in Washington. Whereas women’s participation and representation in partisan politics remained insignificant, ads like the one for Listerine Tooth Paste suggested that “When lovely women vote” their voice mattered, even if it was only with regard to their favorite brand, not government policies.

By pointing to the similarities between women’s role as citizens and as consumers, these advertisements framed consumption not as a frivolous act, but as a parallel arena for women to exert choice and control, using the power of the wallet in political ways. Shopping became a form of political exercise and a democratic means to express American values and freedom.

Despite the empowering messages some of these ads conveyed, they also reduced political participation to a consumer choice, illusorily equating buying products with political power. Despite proclaiming that it is women who sit on “The Supreme Court of Business” — as one ad tried to assure manufacturers — alluding to their influence as consuming arbiters, in reality, very few women could claim such a power. In the actual Supreme Court of the United States, the one that influences women’s lives and legal status, women were not represented until 1981.

If in the 1920s advertisers sought to convince women that their vote mainly mattered in the marketplace, today it is clear that it primarily matters in politics. With the increasing influence and power of women, not only as voters but also as candidates and elected officials, appealing for women “to vote” for the right product no longer suffices. As the growing percentage of women’s participation in elections show, when “lovely women vote” they can not only determine what brand is going to succeed, but also who will be the next president.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Really insightful feature Einav, taking a look at the American woman and the power she possesses as a consumer and decision maker for her family, and herself. I like the simple yet very direct GE ad from 1923 featuring the suffrage and the switch.

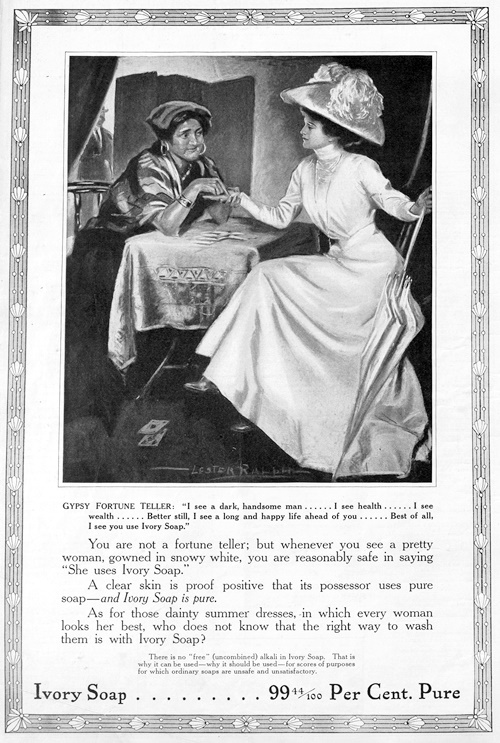

The 1911 Ivory Soap ad wasn’t too bad (for the time) as I’m sure others were back then. I’ve seen a good many print ads between the ’50s and the ’70s (!) that were much worse. This is an older fortune teller, telling this woman all kinds of things she sees, and it’s all coming true because her skin is so lovely thanks to (the product) Ivory Soap.

Having read the ad copy, we must realize it was written and aimed at women born in the 19th century, so we have to give it a break. I really love the beautiful artwork that went into it to make it so visually enticing. 1911 is one of the final years with ties to the 19th. It’s a striking ad I’d love to have framed and hanging on my wall at home.