Today, computers are so ubiquitous as to be almost invisible, or at least sometimes forgotten. Many of our daily computing devices are also wired to the internet. Whether it’s the phone in your pocket or the car you drive, the internet of things has been our reality for some time.

But not so long ago, computers were big and bulky, and mainly dwelled on desks, with their resources either shared out of necessity or at least expensive to access exclusively. In 1982, a professional desktop computer with accompanying software could cost $15,000 in today’s money. A DIY “hobbyist” computer or a stripped-down microprocessor would have been quite a bit less — closer to about $3,000 today — if you knew how to run it.

By the end of the 1980s, these prices were closer to about $1,500, but computers were still mostly fixed in place — in other words, you typically did not take it with you. And even you did, it wasn’t plugged into the commercial internet, as that wasn’t yet a thing.

But for one group of workers, portable computing was becoming the norm, as was sending your work back to the office from the field.

Journalists in the U.S., Canada, and Europe (and not long after, the rest of the planet) helped to pioneer what would eventually result in our mobile world, and did so by experimenting with early modems and the first generation of “laptops” the 1980s. The origin of mobile media work helps us understand how all workers gradually did more of their work on the go during the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Already Mobile

The development of mobile computing for the larger public is often described as a movement in which devices move from “desks to laps, palms, and hips,” a movement that happened in the late 1980s. But news workers deviated from that trajectory as their work was, in a sense, always mobile — they worked remotely even before the advent of computers, with the help of earlier technologies such as telephones and radio cars.

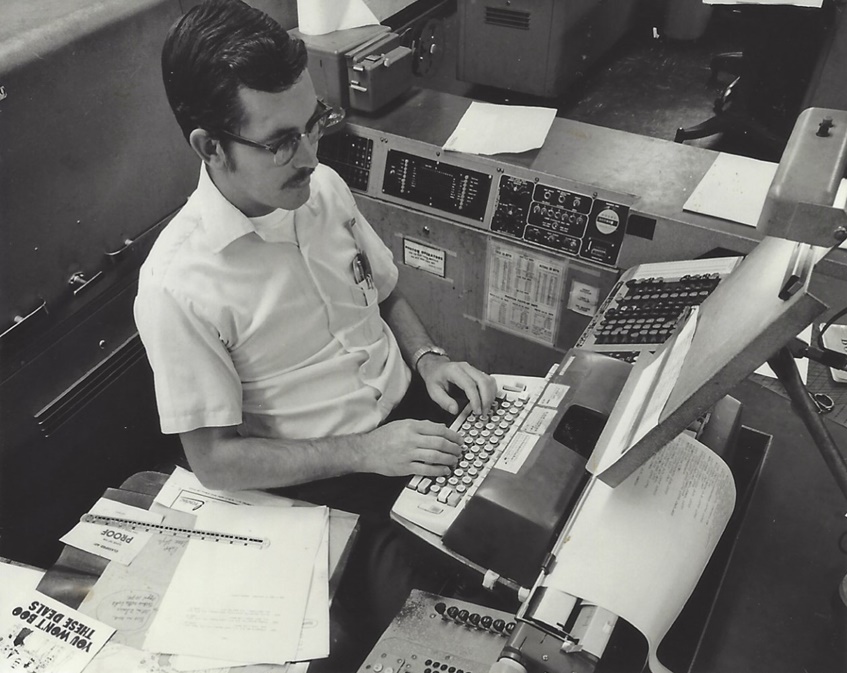

The first generation of newsroom computers actually arrived in the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. These machines were often so-called minicomputers, like the closet-sized PDP-8 from Digital Equipment Corporation, and handled duties such as pagination (how to get the printed version of a newspaper to handle text over multiple pages) or early layout tasks. While there were mainframe computers in a handful of major newspapers and TV networks’ headquarters as early as the 1950s, minicomputers were the first generation of more commonly utilized newsroom computers. In time, minicomputers running small newsroom networks through local area networks (LANs) became common in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, where they ran the computing resources shared by reporters and editors at “dumb” video-display terminals (VDT).

Starting in the mid-1970s and the early 1980s, “micro” or “personal” computers became more common in newsrooms. These small, powerful (for their era) machines functioned as self-contained desktops. While still connected to newsroom LANs, they allowed news workers direct access to databases and more powerful word-processing, number-crunching, and other programs, including early mapping software. Computers were also sources of key changes in the more technical aspects of news making and rapidly played a role in additional advancements in copy editing, layout, and pagination, all of which paved the way for the development of the first generation of content-management systems (CMS).

Mobile technologies, such as portable computers and acoustic couplers (basically early modems), were introduced at the same time as (non-portable) computers were becoming widespread in newsrooms.

Portable Computers

Some early portable computers were created specifically for reporters and editors. One example was the Teleram P-1800, launched in 1975. It was developed as a solution to journalists’ needs, and especially by those expressed by The New York Times. Teleram, a computer company based in White Plains, New York, was founded precisely to cater to journalistic expectations.

The American Newspaper Publishers Association (ANPA) was also involved in the development of the P-1800. The Teleram was featured as early as May 1974 in an article in Editor & Publisher, which announced that “reporters in the field will in the next few months be recognized not by notepad or standard typewriter but by the latest electronic input device.”

According to a news story in the January 1976 in Editor & Publisher, the P-1800 resembled a small blue suitcase that measured “about a foot-and-a half by a foot by a half-foot.” It had a freestanding keyboard and a 7-inch screen that could hold about 125 words. It could be plugged into AC or into a car battery via a car’s cigarette lighter, and could also work on batteries. Data was stored on cassette tapes, and it also featured a built-in acoustic coupler (i.e. modem) on the back. When connected to a telephone’s earpiece via acoustic coupler, the P-1800 could send about 300 words per minute. Since most news stories — especially for breaking news — didn’t run past about 500 words, this was often more than sufficient for a reporter filing a story from the scene of a political convention or tournament.

By 1976, it was estimated that the P-1800 was used by 50 daily newspapers. Prestigious news organizations soon acquired their own Teleram units, including The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker (which invested in Teleram by buying a 35 percent stock interest in the company), and the Associated Press, but also in mid-sized newsrooms such as the South Bend Tribune (Indiana), the Oakland Tribune (California), or The New Orleans Time-Picayune.

Teleram then developed other portable computers specifically designed for newspaper work, such as the “Portabubble,” which owes its name to a then-new data storage technology, bubble memory, used instead of silicon chips. This made the device lighter than its predecessors. At “just” 15 pounds, it became popular because it could “store large amounts of copy” and was more “truly portable,” according to Earl Wilken, the Editor & Publisher reporter in the same 1981 story noted above. Connectivity was an important feature, with the built-in coupler now on top of the device. These features made it attractive to large, well-resourced news organizations such as The New York Times and wire services like the AP, both of which invested in Portabubbles starting in 1980.

Besides Teleram, other companies developed portable computers specifically for journalists. In 1978, Computer Devices Inc. advertised a portable computer called the Miniterm. The device included a printer, mini-cassettes for data storage, and a built-in acoustic coupler that could transmit a 500-word story in 30 seconds. Before this, an editor could review copy one line at a time, transmission speeds had been so slow.

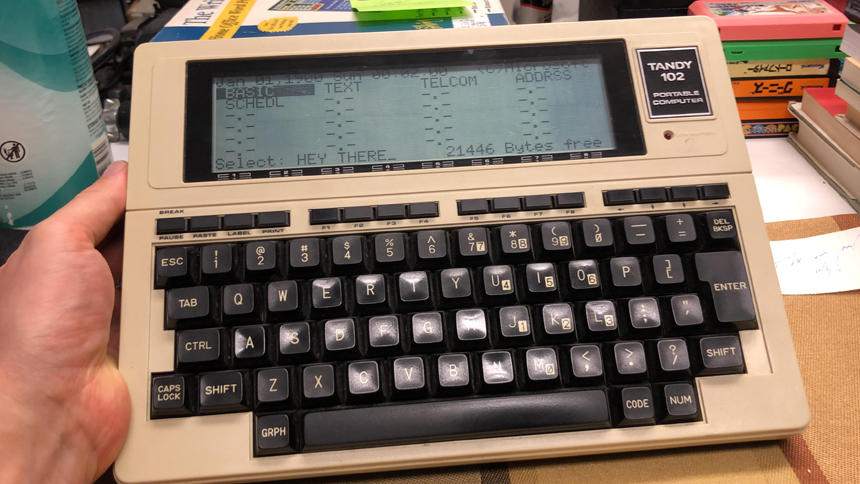

Some enterprising companies packaged acoustic couplers and computers together, as with the “Newsline,” a literal briefcase that included a Tandy Model 100 TRS-80, along with spare acoustic couplers and a cassette recorder, “designed for writers, reporters, or anyone who has a need to create stories and transmit them into a newspaper’s editorial system using voice grade phone lines,” as touted in an ad in the October 29, 1983, issue of Editor & Publisher. The TRS-80, developed by the Tandy Corporation and Radio Shack, and launched in 1983, became especially popular with reporters because of its weight (just four pounds) and its use of AA batteries, along with a simple operating system that made it easy to send stories back to the newsroom via an acoustic coupler.

A journalist who worked as the Mexico City bureau chief for the San Antonio Express-News called the TRS-80 the “jeep of portable computers, reliable most anywhere.” He recalled in an Oct. 2, 1999, story in Editor & Publisher, how, while covering the lead up to the brief American invasion of Panama in late 1989, he had left his TRS-80 under a window air-conditioning unit, and how it had gotten soaked with water as a result. “I freaked out, naturally, but just turned the thing upside down and drained the water out. The next day, the machine worked the same as always.”

Tandy had improved its original Model 100 with updates in 1984 and then 1987 (with a faster processor and more memory), but it was still affectionately called the “Trash 80” by its loyal users.

Specific reporting environments were particularly demanding when it came to imagining where and when a portable computer could be useful to a reporter. At sporting events, portability was judged particularly “important to sports writers when they are trying to get out of a stadium in a hurry and they have other things to carry as well,” according to Editor & Publisher reporter Earl Wilken, in a December 26, 1981, story in the trade magazine.

Portable computers could also make a difference in the coverage of catastrophes and unexpected events. One news worker in upstate New York used his Tandy to report from the site of a plane crash in 1993, transmitting via a coupler, and via an early cell phone. While the signal was weak, it was just enough to send the story’s text, which was printed in his newspaper the next day.

Modem Mania

To be mobile and useful for news workers, computers not only had to be portable, they also had to be able to “talk” back to a newsroom. To do this, the first generation of portables worked with the first commercial generation of modems. These modems were used not to connect to the internet — then not accessible for most people outside of military and scientific circles — but rather to their home newsrooms and to some early pre-internet networks. Once the purview of companies such as IBM and AT&T, by the late 1970s, computer hobbyist and trade magazines such as Byte carried instructions for how to construct these devices at home.

Among other reasons for their prolonged popularity with reporters was their versatility. Reporters working from hotels and older office buildings did not have to rely on outside support to file their stories remotely — or have to physically recite their stories over the phone (i.e. “calling the story in” to rewrite staff). Reporters could capture and transmit the “original keystrokes,” leaving no room for transcription errors or interventions from other news workers in their precious copy, as an ad in Editor & Publisher claimed in the May 8, 1976, issue of the magazine. As a story in an earlier issue explained, this would “eliminate all the laborious and manifold retypings that now occur as a piece of writing makes its way, typically, from reporters through bureaus to the home office to the desks of editors and eventually to linotype machines.”

And one did not have to be an electrical engineer to figure out how to type and then transmit that story directly to another location, in this case, a news worker’s home newsroom.

Paving the Way for an Untethered Future

The history of portable computing is not limited to the history of portable computers. Computers co-existed with a host of other equipment: modems, acoustic couplers, cameras, and microphones, among other devices. This ecosystem of tools mattered, beyond the individual parts. As a new kind of mobile worker who had to defend their place in the intense economy of the 1980s and 1990s, the journalists who worked with portable computers had to be resourceful with filing their stories as fast and as accurately as possible.

The introduction of portable computers was (then and arguably now) discussed as a gain in freedom: freedom for the employer to save on personnel and the cost of paying for long-distance phone bills, and freedom for editors and journalists to work from home, or from the field, and to control their storytelling more fully. But that also came with the cost of being tethered to work while away from the newsroom, much as remote workers today still have to log in to do their jobs.

When thinking about the origin of “work-from-home” tools today, this first use of mobile computing by journalists helps us understand where our connected and simultaneously disconnected work worlds have come from. This isn’t a phenomenon of the past few years, but rather a more spread out, messier story going back to the Cold War. Working away from an office has a long history. And reporters and editors paved the way, for better or worse.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

It’s incredible to see how the early innovations in portable computing not only changed journalism but also paved the way for the work-from-home culture we have today. Amazing how far we’ve come!