On November 12, 1910, The Saturday Evening Post published a short story by Jack London, “The Benefit of the Doubt.” In itself, this was not an unusual occurrence. London had been a fixture of the magazine since their serialized publication of his novel The Call of Wild in 1903. In fact, they had just published his story “When the World Was Young” back in September.

Yet the response to “The Benefit of the Doubt” was anything but usual. Its publication stirred up quite a sensation in London’s home state of California. The newspapers published excerpts. They wrote lurid headlines. They reveled in the details. Why did this particular story, which is not much remembered now, elicit such a frenzied response in California?

Because readers knew the truth behind the tale.

And the truth, as Mark Twain said, is stranger than any fiction.

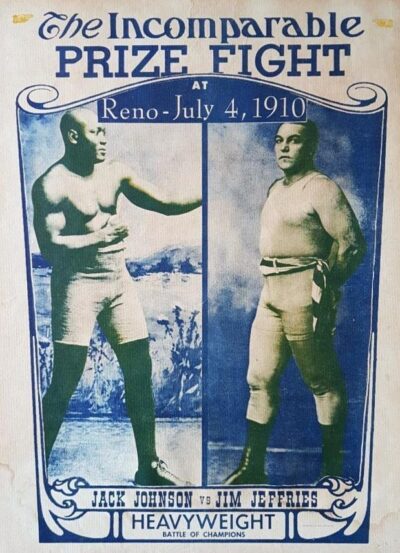

The story of “The Benefit of the Doubt” began earlier that summer, on the evening of June 22, 1910, in an Oakland dive bar. Jack London was in the city making preparations to attend the “Fight of the Century” in Reno, Nevada. Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight champion, was going to battle Jim Jeffries, a former champion who many saw as their “great white hope.” London was on special assignment to cover the event.

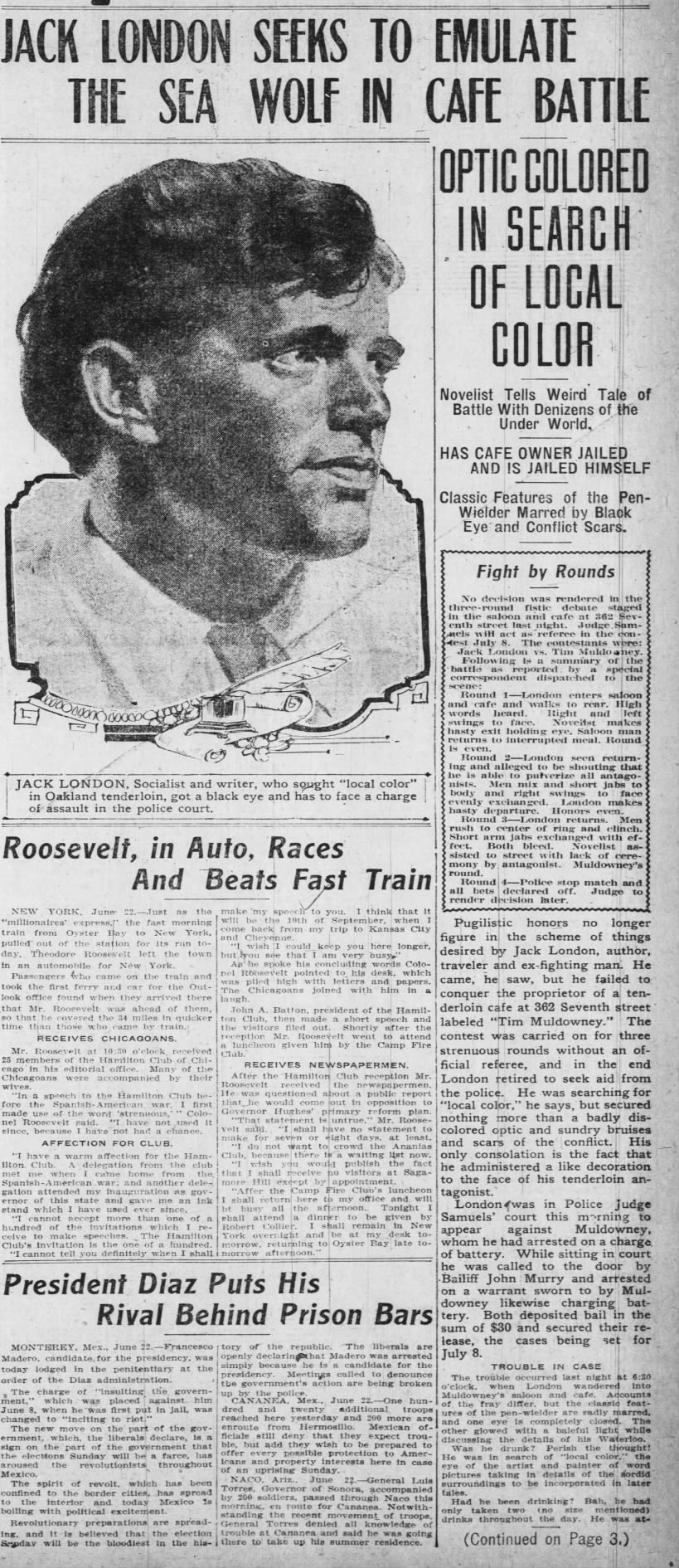

According to The Book of Jack London, he walked the Oakland streets, where he had once lived, noting how the old neighborhood had changed. He purchased several copies of Jeffries’ autobiography, planning to give them as favors in Reno. He had the books under his arm when he entered the Tavern around 6:30 p.m. Newspaper accounts refer to the Tavern as a tenderloin resort,” a colloquialism with distinctly unsavory connotations.

Exactly what transpired inside the Tavern is a matter of some un-pin-down-able controversy. What is known for certain is that the next morning, London appeared in court with a freshly blackened eye. Timothy Muldowney, proprietor of the Tavern, was in court as well, also sporting a shiner.

The two men accused each other of assault, and a pair identical charges were brought up. Police Judge George Samuels agreed to hear their cases jointly, as all the evidence and testimony would overlap. He also agreed to postpone the trial until after the Reno fight, at London’s request. A $30 bail was paid and America’s most famous novelist was released.

The newspapers had a field day. Jack London was big news. At this time, he was one of the most well-known celebrities in the world. The Oakland beat reporters had him in their courtroom and they were set on making the most of it. “Jack London Fights with a Saloon Man” ran the headline. Knowing London’s affinity for boxing, they wrote up the bar fight as if it were a boxing match, including “round by round” descriptions.

Accounts differ in the details, but the generally agreed upon story is that London entered the Tavern and walked down a narrow hallway. The proprietor, Muldowney, alleged London was drunk and disorderly; London maintained he was sober and polite. Some versions suggested London entered the women’s restroom in error. Others say that Muldowney mistook the books under London’s arm for posters, and believed the author was attempting to hang gaudy advertisements for cures for venereal diseases on his barroom walls.

Regardless, Muldowney stood up from the table where he was eating. All versions agree upon this mealtime fact — Muldowney was most certainly eating his supper, although a disagreement arises regarding what Muldowney was eating: soup, in some versions; pork and beans in others. Muldowney approached London and words were exchanged. A physical altercation ensued, ending with London out on the street, where he enlisted the aid of a policeman and began the legal procedure that eventually brought them before Police Judge Samuels.

On July 8, after the Johnson-Jeffries fight (Johnson won, by the way), London and Muldowney went to court. Each blamed the other for the violence. Muldowney’s account paints London as the instigator. One newspaper reported Muldowney claiming London said: “I’m Jack London and I’m going to report the Jeffries-Johnson fight, and I’m a fighter myself and can lick anyone my weight or two like you.” London struck Muldowney first in this version, and after a scuffle, the proprietor prevailed in coaxing London out of the Tavern by use of his foot, literally kicking a belligerent London to the curb.

“Jack London Depicts the Big Fight,” read one headline. “Tells in Court of His Battle with Muldowney.”

London testified that he tried to apologize for the misunderstanding but was cut off repeatedly by Muldowney’s raised voice. Attempting to leave, London found himself being encircled by no less than six of Muldowney’s compatriots. It was then the altercation got physical. London testified he was careful not to injure any of his assailants, knowing that his celebrity status made him a target for litigation. No match for their numbers, the writer ran from the Tavern as soon as he could, where he flagged down the first officer he found.

“London Was Mistaken for Quack, Says Jeff’s Own Book Started Row,” ran a headline. “Heard The Call of the Wild.”

What neither testimony mentioned was the fact that on that day, Jack London was grieving.

Charmian, his second wife, had given birth on June 19th. It was their first child together. Unfortunately, there were complications with the birth. The baby’s spine was broken during labor, and the placenta was not properly delivered. Jack and Charmian’s child was taken immediately into medical care. Joy-Baby, as they had taken to calling her, died just two days later. Charmian had never gotten to hold her.

Charmian remained in critical condition after the difficult birth. The couple was informed of their baby’s death early in the morning of June 22. Charmian remained in the hospital convalescing, but urged Jack to go prepare for his Reno trip. It was later that same day that he went walking the streets of Oakland, the sentence of that unimaginable anguish upon him.

After hearing testimony, Police Judge Samuels ruled that without evidence beyond the conflicting accounts, and given the fact that both men had sustained similar injuries in the fight, he found reasonable doubt regarding both stories. Both cases were dismissed.

Newspapers portrayed the defendants as conciliatory, writing that Muldowney and London shook hands. They even said Muldowney invited London back to the Tavern for a drink, and that London accepted.

This was not the outcome London was hoping for.

He began stewing over the case’s dismissal. Charmian wrote later in her memoir that she had never seen her husband so agitated, especially regarding “the exasperating newspaper lie as to his shaking hands with the dive-proprietor.” Three weeks later, on July 29, Jack London did something no one could have expected.

He publicly threatened the judge.

London sent an open letter to seven local newspapers. The letter was aimed at Police Judge Samuels, with whom London now felt a certain and special grudge. In the letter, London’s righteous indignation was on full display. He accused Samuels of “bullying” him from his “miniature high place.” In pugilistic terms, he described the judge’s ability “to strike and not be struck back,” and he lamented having his testimony held as equal to the “unsavory” Muldowney’s. Such equivalency “was tantamount to finding me guilty,” he argued.

Having stated his quarrel, London closed his letter with a surprising denouement. “And in conclusion, let me tell you this: Some day, somewhere, somehow, I am going to get you.”

It was an extraordinary turn from one of America’s foremost men of letters.

The newspaper reached out to Judge Samuels for a statement. They published his rebuttal alongside Jack’s accusing letter. “I have no controversy with Jack London and I do not want to be drawn into anything of the kind.” He was dismissive of it all, including the threats. “Have I anything against him? No.”

On August 11, less than two weeks later, London sent another open letter to the press. This time, he had an accusation to make. He had checked with the assessor’s office regarding ownership of the Tavern. The name assessed for the lot was a “George Samuels.”

“In the telephone directory of Oakland there is only one George Samuels, and that is Judge George Samuels. So I am writing you to ask if you are the George Samuels who is assessed for Muldowney’s tenderloin resort at 362 Seventh street.”

“What have you to say for yourself?”

The headline: “London Issues Chapter II of War on Jurist.”

Once again, the newspaper reached out to the judge and published his response alongside London’s letter. The judge explained that he did own the land, but had leased it for a period of five years to someone else. It was that lessee, he explained, who built and owned the Tavern. He claimed to have had no knowledge it was the same property when he tried the case.

In the pages of San Francisco newspapers, London had aired the most damning allegations he could summon, and Samuels had countered them effectively. No other tit-for-tat took place. The newspapers had enjoyed the row and pressed it for all the entertainment it was worth, but the show seemed to be over.

Not for Jack London, however. The author still had one more story to tell.

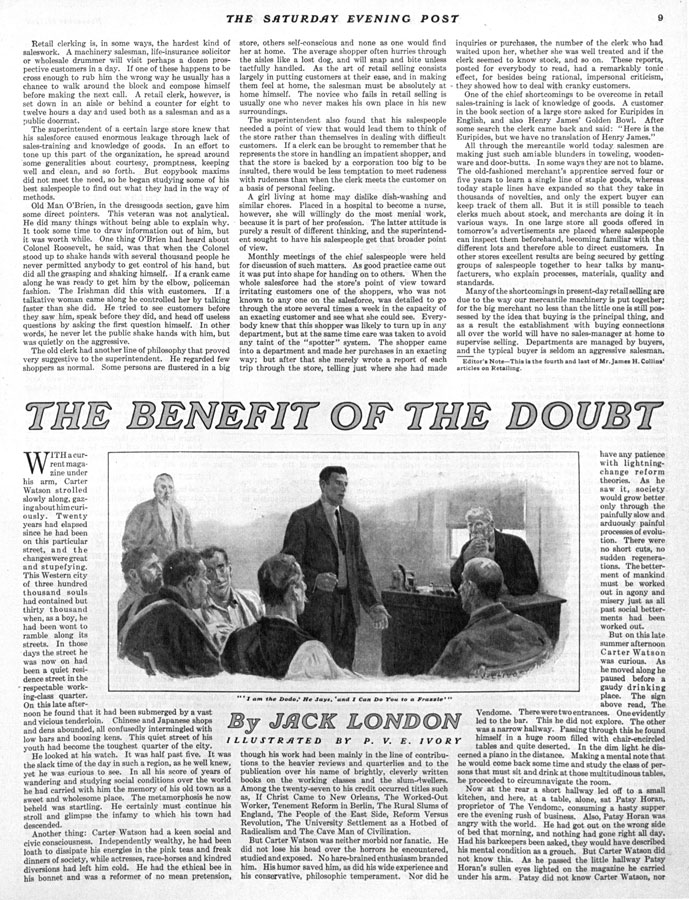

On November 12, 1910, he published “The Benefit of the Doubt” in The Saturday Evening Post, and it does not take a doctorate in English Studies to identify London’s inspiration.

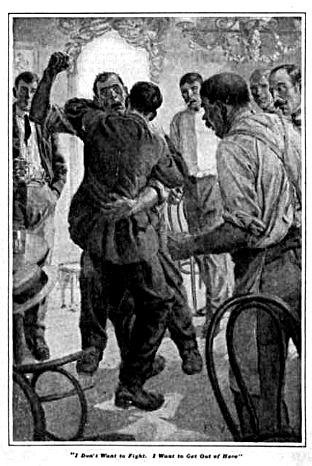

“The Benefit of the Doubt” tells the story of a writer named Carter Watson who is revisiting the streets of his childhood, noting how the neighborhood has worsened over the years. While in a dive bar, the proprietor, Patsy Horan, picks a fight with him. Despite his best efforts to diffuse the situation, he is ganged up on by six of the regular barflys.

Watson prevails upon a nearby policeman for help, only to find the officer is friends with the proprietor, and Watson himself is promptly arrested for assault. Before Judge Witberg, Watson finds himself up against a political “machine” of lawyers, police, and newspapermen all working in chorus.

After a quick and lopsided trial, the judge delivers his verdict: “It is an axiom of the law that the defendant should be given the benefit of the doubt. A very reasonable doubt exists.”

The next day, Carter Watson reads in the newspapers that the judge suggested they shake hands, “which they promptly did.” The newspapers add that Patsy Horan suggests the two go “have a nip on it,” and that the two go off “arm in arm.”

Sound familiar?

Reportedly, the editors of The Saturday Evening Post had insisted on running London’s “fiction” before their legal team to make sure it cleared the bar for libel before they agreed to publish it.

London’s short story does not end there, however. The ending is similar to a scene from the movie Annie Hall, where Alvy Singer has written a play which is an almost word-for-word re-enactment of his failed relationship, except this time he gets the girl.

He turns to the camera, breaking the fourth wall, and offers this mea culpa. “You know how you’re always trying to get things to come out perfect in art, because it’s real difficult in life?”

The end of Jack London’s “The Benefit of the Doubt” involves his stand-in, Carter Watson, having an unplanned encounter with Police Judge Samuels’ stand-in, Judge Witberg. Without giving away too much, London’s fantasy scenario is violent and unsparingly brutal.

Charmian wrote of it later: “Jack worked off, in the fiction, a fantastic revenge.”

Jack London was known as a prominent and committed socialist who signed his letters “Yours for the revolution.” He spoke out strongly against injustices such as child labor and poor food safety. In “The Benefit of the Doubt,” however, London detoured from these more serious ambitions to wallow briefly in his flawed human nature, prioritizing personal revenge.

Whatever grief London had endured, and whatever linkages — acknowledged or otherwise — existed between the death of his infant daughter, the immediate bar fight, and his subsequent fixation on the case, we can only wonder.

It made for a good story, anyway. And it speaks to London’s dedication to his craft that he could experience such a vexing and chaotic year and weave it into a bloody and cathartic tale, all the more satisfying for knowing the facts that buttressed his fiction.

The California papers went wild with the publication of “The Benefit of the Doubt.” Reporters who had done their due diligence earlier in the Oakland courtroom were now enthusiastically reaping this wild and unexpected result.

One newspaper featured a drawing of London on horseback, tilting toward the judge using a quill pen as a lance. “Judicial Gore Spilled in Type, Story Writer Fulfills Threat” ran the headline.

“Author’s Battle with Saloon Keeper Forms Plot of Story,” read another, above photographs of Judge Samuels and Jack London. “The former is attacked by the latter in ‘The Benefit of the Doubt.’”

Another featured a drawing of London and Judge Samuels, both bruised and bandaged and suspended upon the scales of justice, captioned “Here’s the Thriller of the Season; Author Clubs Judge Samuels with His Pen in Fiction Drubbing.”

It was a rare and rousing schedule of publicity for the author and his short story. Even Muldowney was pleased. One of the papers caught up with him and asked what he thought of London’s revenge. Muldowney claimed he purchased copies of The Saturday Evening Post for all his friends.

“Finest ad I ever had,” he boasted.

Three years later, “The Benefit of the Doubt” was re-published along with nine of London’s other short stories in a collection titled The Night-Born, released in 1913. The book received positive though not incredible reviews. Although the San Francisco papers had covered “The Benefit of the Doubt” humorously when it first appeared, national reviewers now struck a more serious tone, appraising it as a solid example of London’s “blood and bones” class of literature. It, along with his boxing story “The Mexican,” were considered the best in the book.

There is an interesting addendum to this story.

In 1996, artist Stephanie Taylor was contracted to paint a mural featuring Jack London and other writers for a wall in Oakland. Taylor had a unique connection to the author: She is the granddaughter of Police Judge George Samuels.

Family lore had always maintained that her grandfather had been threatened by the famous writer, although the details had been fuzzy. While working on the mural, Taylor read her first Jack London stories, and began researching the lives of both the author and her grandfather, Judge Samuels.

“London didn’t hurt his reputation,” she wrote on Zócalo Public Square. “When the judge died in 1925, the courts shut down, and flags flew at half-mast.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Fascinating backstory to a great tale from American literary history. Kudos!

There’s a mystery short-story by Edward D. Hoch where London and Jack Johnson are characters; “Five Rings In Reno.” Hoch stuck to a lot of the historical events of the time.

Muy interesante. Me gustaría ver más sobre boxeo.

Great story, fun history and neat clips from the past. Thanks for this.