“I am most grateful that…I was born long enough ago to have known people who lived in the ancient way before everything started to change.”

–Mourning Dove

Maybe it was because she was born in a canoe on Idaho’s Kootenai River. Or because she was multiracial. Or because she went to a convent school to learn English as a ten-year-old. Whatever the reason, Christine Quintasket, whose Salish language name was Hum-ishu-ma (Mourning Dove in English, which she adopted as her literary name as an adult), wrote stories about the hostility white people had toward Native Americans and the confusion they suffered when educated in white schools.

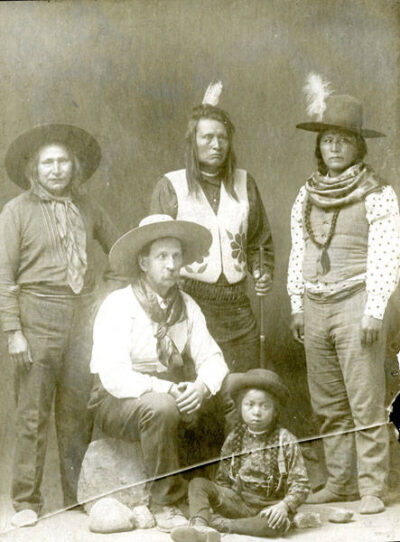

Born around 1884 to Sinixt/Colville Lucy Stukin of the upper Columbia River and Okanagan/Irish Joseph Quintasket of British Columbia, the future writer grew up speaking the Salishan dialect in her mother’s home near Kettle Falls, Washington, according to her autobiography. Mourning Dove’s grandmother taught her the traditional customs of Columbia Plateau natives. Teequalt, an older woman who lived with the family, introduced her to tribal spirituality, and Jimmy Ryan, an adopted white orphan, taught her to read English through dime novels.

As a young girl, Mourning Dove remembered sitting by a campfire and listening to the animated voice of a tribal storyteller imitating an animal. “We thought of this as all fun and play, barely aware that tale-telling and impersonations were part of our primitive education,” she recalled decades later.

Mourning Dove’s indigenous education ended in 1894 when she went to the Sacred Heart School at the Goodwin Catholic Mission near Kettle Falls. When her mother died in 1902, the writer returned home to care for her younger siblings. After her father remarried in 1904, she moved to Great Falls, Montana to attend the Fort Shaw Industrial Indian School. In 1908 Mourning Dove sorrowfully watched the last roundup of America’s wild bison herd as the Old West faded. “One magnificent fellow fought like a lion as they tried to crowd his wonderful shaggy head into a box car,” she told an interviewer. She later incorporated the roundup in her writing.

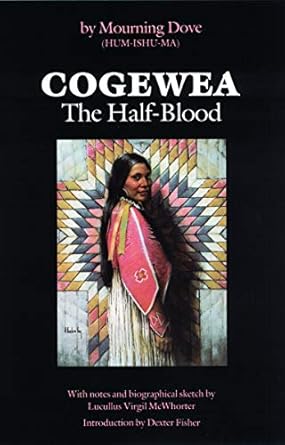

A year later she wed Hector McLeod, a one-armed Flathead native with a “wild lifestyle.” Mourning Dove moved to Portland, Oregon where she began a novel about a multiracial Native American girl named Cogewea. Realizing she needed to improve her written English skills, she crossed into Canada and enrolled at the Calgary College business school to study typing, shorthand, bookkeeping, and composition. Sometime after that she divorced McLeod.

By then she had met Lucullus McWhorter, a white businessman, tribal advocate, and founder of the American Archaeologist. He became so intrigued with Mourning Dove’s unpublished novel that he volunteered to become her editor. In 1916 he tried to sell her novel to publishers, insisting it was an important book since it came “from the pen of an Indian.”

That same year, Mourning Dove told a reporter from Spokane’s Spokesman Review that her novel would transform the white stereotype of the American Indian: “It is all wrong, this saying that the Indians do not feel as deeply as whites. We do feel and…some of us are going to make our feelings appreciated, and then will the true Indian character be revealed.”

McWhorter finally convinced the Four Seas Company of Boston to publish the book, but they insisted that McWhorter and Mourning Dove pay the publication expenses. In 1919 after she married Fred Galler, from the Colville line of the Wenatchee tribe, she joined him as a migrant worker in the hop fields and apple orchards near the Cascade Mountains.

“We move around so much that I am disgusted getting a frame for my tent and making a comfortable place to live,” she wrote McWhorter. “I am trying to write, but lordy, with all these mountain pests, I get frantic.”

Her mentor, meanwhile, continued to edit the book and add new ideas and a style that was more sophisticated than Mourning Dove’s own direct style. Among these additions were epigraphs from western writers, footnotes explaining Okanogan words and tribal customs, passages from his own historical research, and contemporary slang. McWhorter also neglected to show Mourning Dove the final proof before the 1927 publication of Cogewea, the Half-Blood: A Depiction of the Great Montana Cattle Range.

Mourning Dove chided her editor for keeping the alterations from her: “I am surprised at the changes that you made. I think they are fine and you made a tasty dressing like a cook would do with a fine meal….[Still] I felt like it was someone else’s book and not mine at all. In fact, the finishing touches are put there by you.”

Later, more softly, she expressed her gratitude to him. “My book of Cogewea would never have been anything but the cheap foolscap paper that it was written on if you had not helped me get it in shape. I can never repay you back.”

Despite McWhorter’s additions, the book’s heroine, Cogewea, expressed the disapproval Native Americans received when they were educated in missionary and government schools. “We are despised by both our relatives. The white people call us ‘Injuns’ and a ‘good-for-nothing’ outfit. A ‘shiftless’ vile class of commonality. Our Red brothers say that we are ‘stuck up’: that we have deserted our own kind and are imitating the ways of the despoilers of our nationality.”

Reactions to the publication of the book ranged from praise to criticism that the writing was awkward, filled with slang and accusations that McWhorter had written it and simply attached Mourning Dove’s name to garner attention.

Meanwhile, Mourning Dove continued as a migrant worker, but at McWhorter’s encouragement, also collected “folklores” to preserve the fading histories of local tribes. However, since other writers had paid Native Americans for their stories, Mourning Dove was often discouraged. “They are such hard people to get anything from….There are some that are getting suspicious of my wanted folklores and if the Indians find out that their stories will reach print…it will be hard for me to get any more…without paying hard cash,” Mourning Dove complained to her mentor.

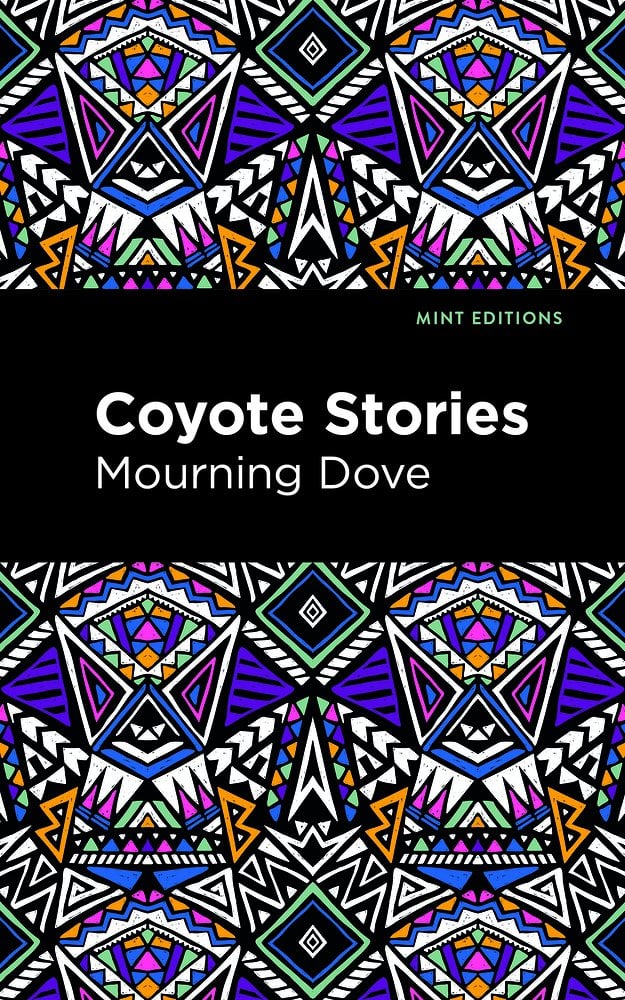

McWhorter then introduced Mourning Dove to Heister Dean Guie, a Yakima City newspaper reporter, who helped the writer with her written English. Before long he also volunteered to join McWhorter as co-editor of the writer’s second book, Coyote Stories of 1933. Since the book was written to entertain children, McWhorter and Guie removed the violence and sex often found in traditional Native American stories, leaving them with little resemblance to the authentic tales.

By the 1930s Mourning Dove had become a spokesperson for tribal rights and spoke to organizations as diverse as the Campfire Girls and the Brewster Women’s Christian Temperance Union in Omak, Washington. Publicly she advocated for fair tribal employment and a greater voice in local Indian affairs, and in 1935 became the first woman to serve on the council of the Confederated Colville Tribes.

Unfortunately, Mourning Dove’s health was failing, and in July 1936 when she was around 50 years old, she was taken to the state hospital at Medical Lake, where she died on August 8. She was buried in Okanogan, Washington as Mrs. Fred Galler. Later the image of a dove flying over an open book was added to the marker along with the inscription “Mourning Dove, Colville Author, 1884-1936.”

In 1990 the University of Nebraska Press published a collection of her other writings called Mourning Dove: A Salishan Autobiography.

But Mourning Dove’s influence extended far beyond her books. Historian Laurie Arnold wrote, “A true public intellectual, Quintasket initiated a ‘renovation of the human estate’ on the Columbia Plateau. Today’s Colvilles continue her work.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I really learned quite a bit about this important Native American author who overcame a lot of obstacles to become the respected published author she became. While it’s sad she passed away at only 52, she accomplished a lot that I’m sure is still helping Native Americans even into the present day.