If you had to make a list of intelligent life-forms on Earth, humans would likely be at the top. Some of our fellow primates like chimps and bonobos would probably come to mind as well. One’s thoughts might also fly to super-smart birds like parrots, crows, and ravens. Marine mammals in general are known for braininess, with many species having complex languages, and some having extremely long memories (helpful tip: Never piss off a dolphin). Speaking of memory, elephants deserve to be listed, as do pigs, dogs, cats, and many other species. But very few people would name bugs, plants, or fungi. And yet, these things have a surprising level of smarts.

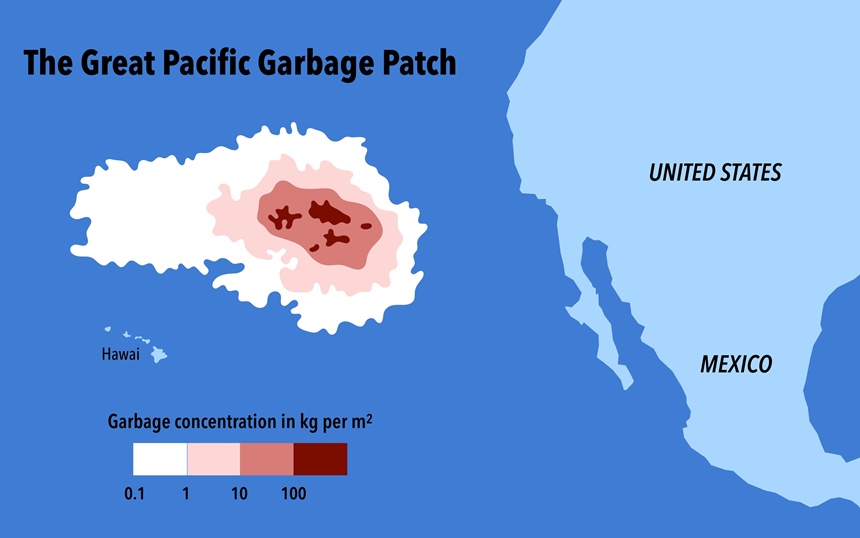

We rarely question our intellectual primacy among animals. It’s true that no other species can point to massive achievements such as the Colosseum, the Eiffel Tower, and an ocean garbage patch three times the size of France. But that doesn’t mean other species are bird-brained.

It makes sense that elephants and whales are whiz-kids, given the size of their heads. Depending on species, whale brains can weigh up to 20 pounds, and Dumbo’s cranium would tip the scale at around 11 pounds. Compared to them, our 3-pound people-brains are small potatoes.

Size matters, but it’s not the only thing. What sets mammal brains apart from other animals’ brains is the neocortex, the outermost region of the brain responsible for higher functions such as language and abstract thinking. And human neocortices, unlike those of most animals, are highly convoluted. This is why we make everything more complicated than we should. Actually, a convoluted brain means a folded one, which gives it more real estate by volume. Imagine if all the states were flat rugs, and you scrunched up Texas (no offense) until it was about the size of Vermont. A lot of acreage can fit in a small space if it’s all valleys and mountains. This greater surface area equates to more processing power than a less highly folded brain.

The ability to make and use tools, and to carry them for future use, is one of the widely accepted indicators of intelligence. In the past, it was thought that only humans and our close ape relatives used tools, such as the orangutans in Borneo that use sticks to spear catfish. But we now know that quite a few critters make and use tools, including elephants, crows, sea otters, and even some fish.

Only just recently has the intelligence of cephalopods like cuttlefish, squid, and octopuses been documented. Octopuses have been seen using coconut shells, as well as human trash, to build structures that they use to hide from predators. If their ability with tools progresses, I bet they could knit an awesome sweater in no time.

We long assumed birds weren’t very smart because their brains are tiny, ranging from pea-sized to about as big as a walnut. Well, we’ve had to eat crow, because bird brains are far more neuron-dense than mammal brains. It’s like we were comparing the microchip brain of birds to our big vacuum-tube human brain and sneering, when in fact some birds test on par with primates for intelligence.

Uploaded to YouTube by the The New York Times

We know that honey bees use an interpretive dance to communicate with each other about the locations of flowers and spilled soda-pop. Bumblebees, though, seem to have one up on them. In 2016, researchers at Queen Mary University of London found that bumblebees learned within minutes how to “play golf,” rolling a tiny ball into a little hole to get a sugar-water reward. I assume the researchers are now busy with bumblebee golf tournaments.

Uploaded to YouTube by New Scientist

Even vegetables can learn new tricks. Experiments showed plants’ Pavlovian-type response when light and airflow from a fan were presented from various sides. We know that plants grow toward light, a form of tropism. But when researchers doused the lights, the plants tilted toward the fan, no matter where they moved it, akin to how Pavlov’s dogs drooled at the sound of bells.

Humans, apes, birds, bugs, and plants show intelligence. But what about fungi? Enter the plasmodial slime mold, a giant, slow-moving, single-cell organism able to scout a new landscape, find the best food, and engulf it, growing ever larger as it slithers along the ground. It should be science fiction: a blob of pink, yellow, or white slime, up to three feet across, that moves with intent. Although slime molds can be alarming at first sight, they’re totally harmless. Usually found in shaded forest environments, they can also appear on mulched flower beds if it stays wet enough. A friend once sent a picture of a slime mold that nearly engulfed an empty beer he left on a picnic table overnight.

A slime mold time lapse (Uploaded to YouTube by BBC)

Researchers in a 2015 study conducted at New Jersey Institute of Technology found that plasmodial slime molds use complex algorithms to make logical decisions about the best direction to go as they slime across the ground. One of the lead researchers said that studying slime molds made him reconsider his ideas about what level of “biological hardware” was needed for an organism to show intelligent behavior.

The folks at Amherst, Massachusetts-based Hampshire College took things a few steps further in 2017 when they named a species of slime mold a “scholar in residence.” The college website says that it “…arrived from Carolina Biological Supply in 2017, and moved into a dedicated office in the Cole Science Center.” Apparently, slime molds have a lot to teach biology students, but bet it’s real hard to understand their lectures.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I don’t know if I’d put humans at the top of intelligent life-forms. as they seem to be getting dumber by the day, it’s a chilling thought. Overall I do agree. The top percent does makes up for a lot otherwise; as it has to! There’s a lot of fascinating info here. I appreciate the video links you’ve included.

The crows, bees and the mould time-lapse. So much to learn and think about here we don’t usually think about on our own, ya know? I’m almost positive if human eating utensils were left out for chimpanzees, they’d figure out how to use them pretty fast. Especially the spoon, probably first.