When you hear the word Thanksgiving, what comes to mind? For many Americans, the mere mention of the annual feast conjures up images of turkey, cranberry sauce, and pumpkin pie. Beyond Thanksgiving dinner, the holiday is a time to gather with family and friends and express gratitude for the good things in our lives.

But have you ever wondered how Thanksgiving became an annual tradition? And why it is celebrated on the fourth Thursday in November?

The holiday traces its roots to 1621, when Pilgrims at Plymouth celebrated a successful harvest with a three-day gathering that was attended by members of the Wampanoag tribe, remembered today as the “First Thanksgiving.” However, colonists didn’t call it Thanksgiving, and they didn’t do it every year.

During the American Revolution, days of thanksgiving were often observed after military victories. But it wasn’t until October 3, 1789, that George Washington issued his Thanksgiving Proclamation designating Thursday, November 26, 1789, as a “day of public thanksgiving,” marking the first national celebration of a holiday.

Later, President Madison declared April 13, 1815, a day of thanksgiving to commemorate the end of war with Britain — the last such proclamation by a president before the Civil War.

Individual states marked many days of thanksgiving, at different times and for different reasons, but for a long time there was little call for a national thanksgiving holiday.

That changed with Sarah Josepha Hale.

Born and bred in New Hampshire, Sarah, like many New Englanders, celebrated Thanksgiving as an annual autumn event. She enjoyed the family warmth and sumptuous feast so much that she wanted to share it with others.

In 1827, five years after her husband’s death, this widowed mother of five — best known at the time for penning the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb” — published the popular novel Northwood; a Tale of New England, which described the region’s virtues and customs. In it, she devoted an entire chapter to a detailed description of a traditional New England Thanksgiving meal: “The roasted turkey took precedence on this occasion, being placed at the head of the table …, sending forth the rich odour of its savoury stuffing. There was a huge plum pudding, custards, and pies of every name and description ever known in Yankee land; yet the pumpkin pie occupied the most distinguished niche.”

She also wrote her hopes for the holiday into a later edition of the novel: “When [Thanksgiving] shall be observed, on the same day, throughout all the states and territories, it will be a grand spectacle of moral power and human happiness, such as the world has never yet witnessed.”

In 1828, following the success of Northwood, Hale was invited to become editor — or editress, as she preferred — of Ladies’ Magazine, which in 1834 was renamed American Ladies’ Magazine, reflecting the publication’s focus. Louis Godey, who had been publishing his own women’s magazine, Godey’s Lady’s Book, since 1830, bought American Ladies’ Magazine in 1837, merged the two, and kept Hale on as its editress.

The revamped publication, which retained the name Godey’s Lady’s Book, became the most widely circulated women’s magazine of its time. Hale’s work with the magazine made her one of the most influential voices in the 19th century, and she used her platform to support various causes, including the education of women, abolition of slavery, and preservation of historic sites, as well as her personal mission to create an annual, national Thanksgiving holiday, believing that it could help ease growing tensions between the North and South.

Through Godey’s Lady’s Book, Hale campaigned to hold a national Thanksgiving day in November. In the pages of the magazine, she published recipes for traditional dishes and wrote numerous editorials making the case for the holiday. A persuasive writer, she urged readers to lobby their representatives and to write to her about their Thanksgiving experiences. They did, and Hale kept count each year of the growing number of celebrants.

Starting in the 1840s, she also wrote letters, hundreds of them, to presidents, elected officials, and military leaders asking for their support. Her requests for recogition were largely ignored, but she never gave up.

Shrewdly, she reminded readers that Washington’s birthday and the Fourth of July were the nation’s only holidays, and both marked wartime successes and reflected men’s “patriotic and political” events. “Should not the women of America,” she wrote in one editorial, “have one festival in whose rejoicing they can fully participate?” A widely observed Thanksgiving would recognize women as caretakers of the home, hearth, and family in which everyone could celebrate.

The last Thursday in November, she informed readers, was the ideal time for a celebration, for by then, “the agricultural labors of the year … and the elections” had ended, and travelers had returned home. Hale selected Thursday as “the most convenient day” in the week for the celebration so that women would have time to prepare the meal.

And after all, Hale pointed out, George Washington, in his 1789 Thanksgiving Proclamation, had chosen Thursday as well.

As the population grew and expanded westward, Hale saw the country change and believed a national Thanksgiving day would bring all Americans to unite “as one Great Family Republic” and “awaken in American hearts the love of home and country.”

In November 1852, as her campaign gained momentum, Hale gleefully wrote, “Last year, twenty-nine states, and all the Territories, united in the festival. This year, we trust that Virginia and Vermont will come into this arrangement.” An editorial in 1855 boasted, “The readers and friends of the ‘Lady’s Book,’ that is, a large majority of the people of these United States, agree in our petition. Let us have a National Day of Thanksgiving on Thursday, the 29th of November.”

Since even a groundswell of public opinion could not legitimize Thanksgiving, Hale also wrote directly to Presidents Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan. None of them supported the proposal.

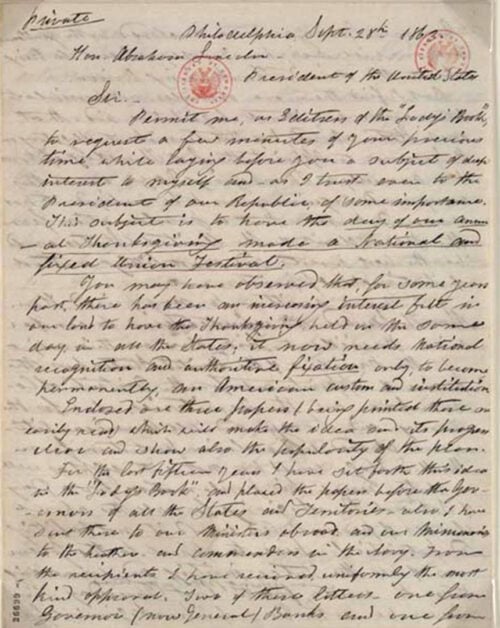

Finally on September 28, 1863, Hale wrote to President Abraham Lincoln explaining that the purpose of her letter was “to entreat President Lincoln to put forth his Proclamation, appointing the last Thursday in November … as the National Thanksgiving.… Thus by the noble example and action of the President of the United States, the permanency and unity of our Great American Festival of Thanksgiving would be forever secured.”

Five days later, at the height of the Civil War, President Lincoln issued a proclamation “to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens … and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation.”

Hale was thrilled but not satisfied; the holiday still depended upon the whim of each president. “As things now stand, our Thanksgiving is exposed to the chances of the time. Unless the President or the Governor of the State in office happens to see fit, no day is appointed for its observance. …Should not our festival be assured to us by Law?” she asked her readers in 1871.

More than 70 years would pass before the U.S. Congress approved legislation in 1941 ensuring that all Americans would celebrate a unified Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday of November every year. Hale’s dream of a legal holiday celebrating the blessings of life and family finally became a reality.

This November, as you sit down to enjoy the meal, take a few moments to remember Sarah Josepha Hale, the Mother of Thanksgiving.

Nancy Rubin Stuart is an award-winning author and journalist. Her most recent book is Poor Richard’s Women: Deborah Read Franklin and the Other Women Behind the Founding Father. Find out more at nancyrubinstuart.com.

This article is featured in the November/December 2025 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Very well written article! I do agree with Midnight Rider that the Canadian Thanksgiving date in October makes much more sense than the last Thursday in November.

I agree with the thought of giving thanks for all we have and get and less of the give-me gang that seems to use the holiday for their own good

God Bless Her!!!

The only thing that would make Thanksgiving better would be to make it a Monday holiday, as they do in Canada. In fact, I think our Canadian neighbours have it right with our (U. S.) Columbus Day holiday being their Thanksgiving Day. Why can’t we celebrate it the same time as they do? Let’s do away with all the Black Friday madness which is unnecessarily stupid.

I give thanks to you Nancy, for this companion feature on Ms. Hale, and how she basically single-handedly brought about the Thanksgiving holiday as we’ve known it in the modern sense, through her core belief in its importance. Her tenacity is amazing to me. I’m disappointed that the 4 Presidents prior to Lincoln did not support her proposal.

This includes other elected officials who either ignored or scoffed at the proposal as well. She knew she was onto something which fueled her desire to make Thanksgiving a reality, and not subject to whims and what not. She knew it had to be official and legitimized—by Law. Thank you for including the handwritten letter to President Lincoln here. Her beautiful handwriting didn’t hurt either. I must say, I love her silhouette too. Thank you.