It All Began with Ben Franklin

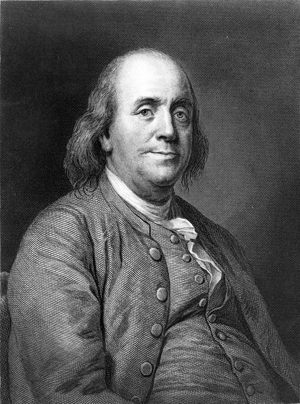

In 1728, 22-year-old Benjamin Franklin came up with an idea for an informative magazine for the colonies. It would be titled The Pennsylvania Gazette. Before he could begin production, though, the idea and name were stolen by an unscrupulous partner. The partner began publishing the magazine, but, within the first year, failed.

Franklin and another partner took over production. Their Gazette carried news and contributions on various topics from readers. Many articles were written by Franklin himself. The paper reflected his interests in the world, science, and government. It also reflected his politics. Franklin had a good sense of what people wanted to read, which allowed him to make the Gazette the most popular publication in the American colonies.

In 1748, Franklin, satisfied with the fortune he’d made from his businesses and inventions, retired from his many enterprises to pursue scientific research and public projects. The Gazette continued publishing, outliving Franklin by 10 years.

It ceased publication in 1800, but Franklin’s old print shop remained in business at No. 53 Market Street, Philadelphia, four doors down from Second Street.

The concept of The Saturday Evening Post didn’t originate with the print shop’s owner, Samuel Atkinson. It came from Charles Alexander, who had the idea of printing a popular poem about a blind girl in the city who set type by hand. Once Alexander had gathered a list of 200 subscribers to the poem, he suggested that Atkinson use the opportunity to start a newspaper.

Atkinson agreed. The new publication would be called The Saturday Evening Post because it would be printed in time to be delivered to Philadelphia addresses in the second mail delivery on Saturdays. (The U.S. Mail was delivered twice daily until 1950.) Pressmen often had to work the hand-operated press through Friday night to complete an edition on time.

In those early days, the Post’s press room took up the lower floor. Editors and type-setters worked on the second floor. The office of the editor, T. Cottrell Clarke (and later Morton McMichael), was in the attic.

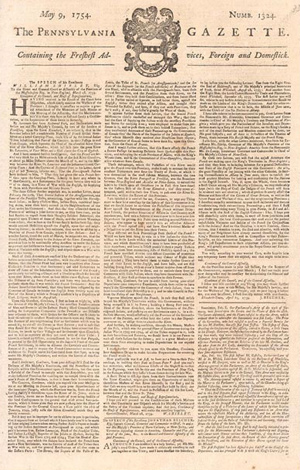

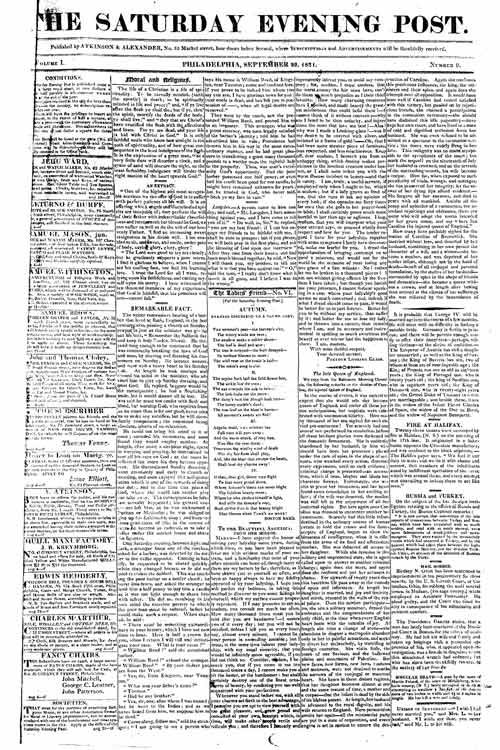

An early history claims the Post’s first issue appeared on August 4, 1821. This coincides with the earliest issue of the Post now held in its archives, which is identified as Number 9, and was published on September 29, 1821.

In addition to local news, the issue carried news of national events, like the correspondence between ex-presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, then both still alive. It also followed international news, reporting the death of Napoleon, for example.

Not only did Atkinson use Ben Franklin’s old printing press, he also used his style. The Post’s contents were written with a tone that was pragmatic, open-minded but skeptical, and moral, though with a sense of humor. It covered a bit of everything about America: business, law, exploration, fashion, etiquette, agriculture, and science.

The Post didn’t operate with a large staff of journalists and researchers. It relied on other newspapers for much of its content, and it expected that its own content would also be freely used by other publications.

The Post’s owners and editors changed frequently in those early years. Samuel Atkinson’s son became sole proprietor and went through five different editors in 18 years (Joshua L. Taylor, Charles J. Peterson, Rufus W. Griswold, H. Hastings Weld, and Henry Peterson).

John Stephenson Du Solle and George Graham purchased it in 1839, before it passed in 1843 to Samuel D. Peterson & Co.

During all those years, The Saturday Evening Post chronicled the changing fortunes of the country: the building of the transcontinental railroad, the gold rush, and the settling of the western territories. It also brought reports of several conflicts: the Mexican-American War in 1846, the Civil War in 1861, and the American Indian Wars of the 1880s.

The publication gained a national reputation for the high quality of its content. Other journalists praised it as the oldest family newspaper in the country, one that avoided any hint of sensationalism.

In 1871, reviewer Eugene H. Munday wrote in The Saturday Evening Post, “Nearly all the prominent writers of the country, for the last fifty years, have contributed to its columns, and the reputations of many were established through its agency; but many who glowed with pride at their maiden efforts in its pages now sleep in forgotten unknown graves.”

The Post also published authors who are still well remembered, such as Edgar Allan Poe, James Fenimore Cooper, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Washington Irving, and Mark Twain.

But the Post began losing its way in the late 1800s. By the 1890s, it had become a sleepy little weekly paper filled with trivia, fashion news, essays, and poetry, but without any illustration and with virtually no advertising. The owner kept it going more out of respect for its being the oldest magazine in the country than to bring fresh, interesting content to readers. Its circulation sank to 2,000.

Cyrus Curtis and “The Singed Cat”

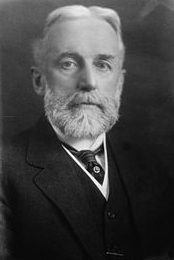

Cyrus Curtis showed an interest in publishing when he was 15, selling newspapers in his home town of Portland, Maine, in 1865. Rather than selling his papers on the same street corner as other newsboys, he rowed out to a nearby island where a garrison of soldiers was stationed. The soldiers, who were unable to get news any other way, bought all the newspapers Curtis could bring them.

That same year, Curtis began publishing his own magazine, The Young American, but the fledgling paper was destroyed, along with his home, in a city-wide fire in 1866. In 1872, he moved to Boston and began a business magazine, People’s Ledger. It, too, was destroyed by a fire.

Undeterred, he moved to Philadelphia because he heard printing costs were much lower there. He first learned the market by selling advertising for The Philadelphia Press. In 1879, when he inherited $2,000, he started a weekly paper, The Tribune and Farmer.

In 1883, he decided to include a page of items that would interest women readers. After writing “Women at Home,” he showed it to his wife. When she criticized his work, he asked, “I suppose you could do better?”

“Yes,” she replied, and so he handed the job over to her.

Readers responded enthusiastically to what she wrote. She began writing this feature regularly, and sales of the Tribune and Farmer rose sharply. The women’s feature grew into a supplement, then into its own magazine. Originally called the Ladies Journal, the name was changed to Ladies’ Home Journal in 1899 when reached a circulation of 500,000. (Eventually, it would become the first American magazine whose circulation reached one million.) That year, Curtis hired a new editor for this publication, Edward Bok.

Reasoning that he’d been so successful with a women’s magazine, Curtis wondered what how he would do with a magazine for men.

Meanwhile, The Saturday Evening Post was barely scraping by with a circulation of 2,000. When the owner died, the Post’s editor came to Curtis for help. Curtis had been considering purchasing the Post. He knew it had a long history and a great reputation, mostly resting on its former glories. He also admired Ben Franklin, whose Pennsylvania Gazette had been the inspiration of the Post.

In researching the deal, Curtis discovered that the Post’s owners had never copyrighted the name. Hence, if it missed a single issue, the publication would forfeit rights to the name and it could be used by anyone. Since the Post was about to miss its next issue, the magazine really had nothing to sell Curtis.

Yet in 1897, Curtis generously paid $1,000 ($60,000 in today’s dollars), hauled the type to his office, and turned out the first issue from The Curtis Publishing Company.

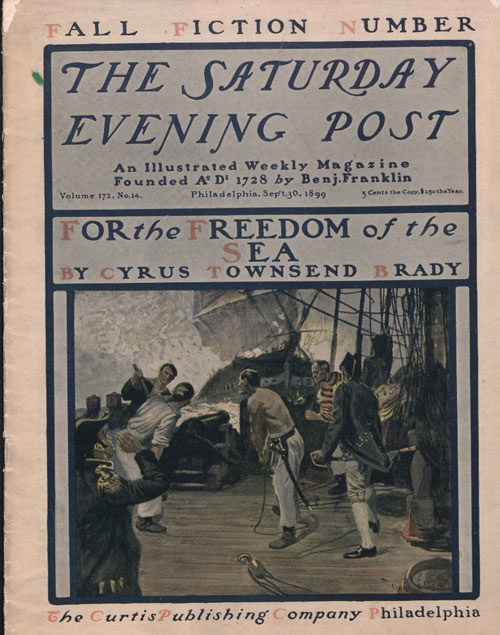

Curtis began to improve the paper, bringing fresh content and redesigning the pages. In 1899, the first full-cover illustration appeared. The old subscribers didn’t like the change and began to drop their subscriptions.

Curtis believed in business. Specifically, he believed business, if properly reported, was a subject of inextinguishable interest in that entrepreneurial era. He wanted the Post to offer men the romance of business. They would want to learn of others’ experiences, failures, and successes in the business world. Curtis couldn’t find a writer to do justice to the subject, so he began writing articles himself.

Meanwhile, the printing industry watched Curtis take profits from the Ladies’ Home Journal and sink them into his new enterprise. Even employees at Curtis Publishing saw little promise in the magazine. In the press room where the Ladies’ Home Journal was printed, employees referred to the Post as “the singed cat.”

As if losing subscribers weren’t enough, Curtis cut the price of the magazine from a dime — the standard price from the big names in magazines — to a nickel. He also sank a quarter-million dollars into promotional advertising. When nothing resulted, he put another $250,000 into advertising the Post.

Slowly, circulation began turning around. By 1900, it had reached 250,000.

By now, Curtis’s bookkeepers warned him, he had invested $800,000 into the magazine. Curtis reportedly said, “That gives us a margin of $200,000 more to make it a round million dollars.” He proposed putting that money into more advertising. “That’ll bring it up to the $1 million mark and then we’ll know where we are.” Ultimately, Curtis invested $1.25 million into the publication, the equivalent of $35 million today.

By 1908, circulation reached one million and continued to climb.

Secrets of Curtis’s Success

In the 1970s, Edward Von Tress, 33-year veteran of the Post’s circulation department, looked back on what made the Post so successful. Much of the success was Curtis’s administrative genius.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Von Tress said, the cost of editing, printing, and delivering a single copy was between 20 and 40 cents. Yet Curtis was charging only a nickel per copy. The only way he could stay in business was to make advertising revenue cover nearly all the costs of publishing. In the 1900s, this was a new concept. The modern advertising industry was just beginning, and few were aware of how much money would eventually flow into ad budgets. Until that time, very few, if any, magazines had enough advertising to make any serious contribution to operational costs. Curtis foresaw that advertising would support big media.

Curtis also had the foresight to hire Charles Coolidge Parlin to study the future of the automotive industry and, incidentally, create the modern marketing study.

Curtis zealously protected the reputation of his magazines. His publications would never accept questionable ads. The Post retained a censor to monitor the advertising appearing in its pages, and, by running only ads that were wholesome and honest, the Post acquired the loyalty of readers. Curtis went even further by only running ads that came from reputable advertising agencies. Eventually other magazines adopted this policy, which helped launch the modern advertising industry.

The last element that made the Post such a powerhouse at the turn of the century was that Curtis trusted his people. He would never influence or override an editorial decision. He assumed he had hired competent editors, and he stayed out of their way.

The Post’s success was Curtis’s success. While the magazine was enjoying the status of being the most popular magazine in the world, Curtis acquired a fortune that, adjusting for modern currency, was close to $50 billion. According to Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers: The Story of Success, Curtis was the 51st richest person ever, with a fortune of $43.2 billion adjusted for inflation (to 2008 dollars). That made him wealthier than J. P. Morgan.

The Age of Lorimer

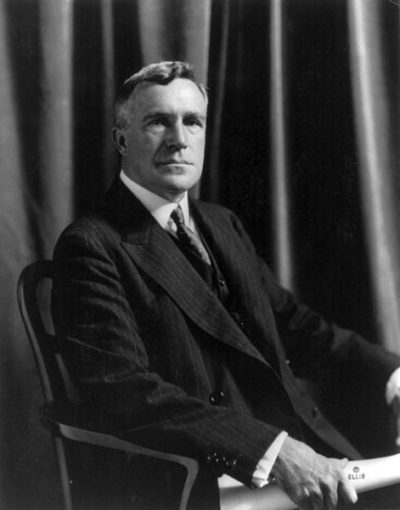

Cyrus Curtis had said, “Get the right editor and you’ll get the right magazine.” Two years after taking over The Saturday Evening Post, he believed he’d found the right person, a journalist who was then in Europe. Curtis boarded a liner and sailed off to meet him in Paris. He left the magazine temporarily in the hands of a promising 32-year-old literary editor named George Horace Lorimer.

The son of a minister, Lorimer grew up an earnest, hard-working, solidly moral man. But he was far from provincial in his outlook. He traveled throughout the country with his family and had seen most states before he left for college.

After the family settled in Chicago, Lorimer — then in school — happened to meet his father’s friend, P.D. Armour of Armour & Company. Armour convinced Lorimer that further study was a waste of time. The best place to study business was in business. If Lorimer would come work for him, Armour said, he’d make him a millionaire.

Lorimer left college, entered the meat-packing business, and started to rise in the organization. After seven years, though, he suddenly quit to become a writer. He began studying English literature and was hired by The Boston Post.

Though still inexperienced, Lormier learned of Curtis’s search for a new editor for the Post, and Lorimer applied for the position. Not surprisingly, he didn’t get the job, but he was hired “to do anything he could,” with the possibility of eventually becoming the magazine’s literary editor.

He proved so capable that he was given the job of temporary editor until Curtis returned from Europe with his candidate for editor-in-chief. But Curtis missed meeting the prospective editor in Paris, and by the time he returned to America, he realized Lorimer was the editor he had been looking for.

On the June 10, 1899, the name “George Horace Lorimer” first appeared on the masthead of the Post. It would remain there through 37 years of incredible growth.

Like Curtis, Lorimer was ambitious. He believed in pursuing great things. He wanted to create a publication that would speak to the entire country.

At the time, magazines had been pitched to regional audiences or readers with special interests. No one had presumed that one publication could fit the interests of an entire country.

But that was Lorimer’s goal.

He set out to interpret and reflect America to itself. The Post would be the first magazine the entire nation had in common, and he’d achieve national acceptance by producing a wholesome, positive magazine that appealed to intelligent readers living the good American life.

He was so intent on not following any trends in the publishing world that he wouldn’t read any magazine other than his own to avoid imitating them.

Finding Fiction

Lorimer sought the best writers in the country. He instituted a policy of reviewing manuscripts faster than any other magazine — the Post decided on submitted work in 24 to 72 hours. And when it accepted a story, it paid the author on the first Tuesday after acceptance. This was remarkably quick; normally, authors had to wait months, even a year before payment. Naturally these policies encouraged writers to consider the Post first, which gave the magazine the pick of new material.

Lorimer was also ready to pay to obtain the best writers of the day. In the 1900s, this meant authors like Joseph Conrad, O. Henry, and Rudyard Kipling (Lorimer turned down several stories by Kipling before the famed British author submitted something he liked). The Post also premiered Jack London’s Call of the Wild.

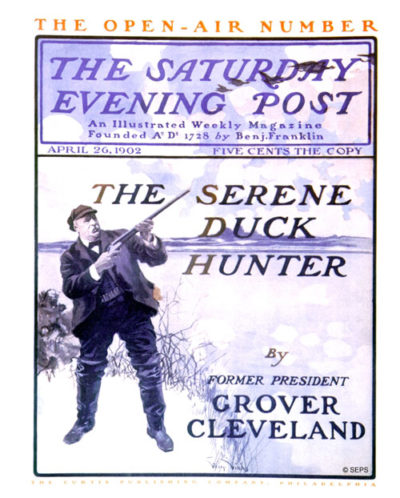

Lorimer also managed to talk former president Grover Cleveland into writing a series of articles. Other politicians with a progressive slant appeared. Senator Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana appeared nearly every week. In one article, he predicted the Russo-Japanese War and its outcome two years before it occurred.

The Post also featured some of the great novels of the day. Owen Wister wrote stories based on his experiences in the West. After their appearance in the Post, he wove them together into the novel The Virginian, considered the first modern western.

Lorimer trusted his instincts. He had a feeling for which fiction would work, and he held his ground against editors who argued against his choices.

In 1909 Montague Glass created a story with two Jewish characters, Potash and Perlmutter, who appeared regularly in an extremely popular fiction series.

And in 1914, Post author Ring Lardner used his mastery of colloquial American speech to reproduce the semi-literate letters of a loutish bush-league baseball player. The “You Know Me Al” series first appeared in March 7, 1914, and was received enthusiastically across America.

Lorimer published both of these successes over the objections of his staff.

Like Curtis, Lorimer believed in the romance of business, but he found very little good writing on the subject. Then, in the spring of 1899, he found The Market Place by Harold Frederic. This story of a self-made millionaire became the magazine’s first serial, and the first installment was very popular — but Frederic died before he could produce more.

Lorimer decided to fill the gap himself. In 1901, he started a series of letters from a fictional father to his son, who was just starting out in business. He based the father on his old boss, Philip Armour, as well as other successful businessmen he knew. Lorimer wrote from his own business sense in these instructive, practical, and humorous letters. Ben Franklin would have approved.

The series, Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son, was so popular, it drove up Post circulation in 1902 beyond 500,000.

In 1903, the Post published another serial about speculation trading in Chicago, “The Pit,” by muckraker Frank Norris. When Letters and The Pit were later published as books, they became national best-sellers.

Early Cover Art

Contributed by David Apatoff

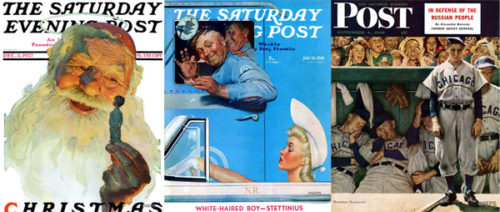

George Horace Lorimer also made The Saturday Evening Post famous for its colorful covers.

In his 1948 history, George Horace Lorimer and the Saturday Evening Post, John Tebbel wrote that the cover images “were easily the Post’s most distinctive feature, its most popular single item and its greatest sales asset.” Lorimer always chose the cover personally, applying very exacting standards. He would never trust such an important decision to a mere art director, as Tebbel wrote:

Lorimer picked the covers as a weekly routine, with the same unerring judgment he exercised on the editorial content. Fifteen or more cover candidates would be lined up on the floor, leaning against the wall, and the boss would walk past them like a general reviewing troops. As he made his rapid progress he would stab at them with a finger and keep up a running monologue: ‘Out, out, out, maybe this one, maybe, out, out, this one.’…. His genius for picking covers was affirmed time and time again by the evidences of their enormous popularity. In some Midwestern communities there were groups of readers who maintained betting pools on the topic of the next week’s cover.

So it’s hard to imagine that, for much of its history, the Post had no cover picture at all.

The magazine began as text densely packed into tight columns on both sides of the page. It was up to the reader to visualize whatever was going on in the articles they read. The Post’s creative “look” was limited to a few different styles of typography. In fact, the Post might never have had its famous cover pictures if three crucial developments hadn’t come together simultaneously at the end of the 19th century. If any one of those developments had not taken place, the magazine revolution might not have conquered the world. As it was, the Post combined those developments to become the most popular magazine in the country.

Development No. 1: A New Kind of Paper Was Invented

In the beginning, paper was expensive, so magazines couldn’t afford the luxury of large pages and the empty white space necessary for illustrations and modern design. Through most of the 19th century, magazines were printed on paper made of “rag” content. Rag paper became even more expensive after the Civil War when supply could not keep up with increasing demand. After much experimentation, the paper industry finally produced new kinds of paper from wood pulp, paper that was strong enough to be used in the new high-speed rotary presses and durable enough that it didn’t fall apart after multiple readings. It was clean and white, making a good platform for reproducing images. And perhaps best of all, the new paper was only 1/20th the cost of rag paper, so it gave magazines creative freedom to design larger and longer magazines with all kinds of eye-catching and imaginative formats. The cheaper paper reduced the price of magazines, making them accessible to masses of readers who previously couldn’t afford to subscribe.

Development No. 2: Better Ways of Reproducing Pictures Were Developed

When the Post began, it was difficult to print even the most basic black and white images, and they rarely turned out well. Crude images — silhouettes of heads, pointing hands, or simple graphic symbols — were occasionally inserted into the text to sustain the interest of readers and give their eyes a little rest from long, monotonous columns of words.

These images were printed using woodcuts or wood engravings, carved by hand into actual blocks of wood, then inked and pressed against paper. This meant the images couldn’t be too complicated, and they couldn’t be in color. They also couldn’t be used for high-circulation magazines because the wooden blocks would wear out.

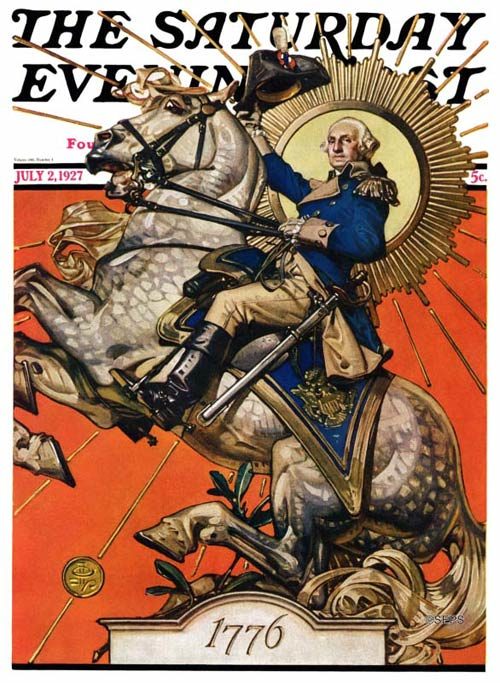

But by the end of the 19th century, printing innovations enabled magazines to reproduce a wide variety of expressive, interesting illustrations. Photographic processes replaced the old-fashioned wood engravers. Quality artists were attracted to the field when they discovered their work could be reproduced accurately. Vivid color reproduction and halftone engraving served as a magnet for new readers. The first color cover of the Post appeared on September 30, 1899, at the beginning of a great surge in the Post’s circulation.

The new technique for printing pictures was a great boon for magazines, but even more changes were in store for the magazine business.

Development No. 3: A New Business Model Was Established

Magazines were originally paid for solely by subscribers. As magazines learned to print more copies using new high-speed printers and deliver those copies to homes across a wider area using improved transportation, subscription lists grew. However, even magazines with many new readers could never afford to hire the most talented artists in the land to paint large, full color oil paintings for illustrations. The crucial difference was a new business model: mass marketing.

For Lorimer, advertising revenues were the engine that would power the growth of the new Post. The first full page illustration in the Post was not the cover but an advertisement for Quaker oats. Lorimer believed he could attract more readers with pictures, and that increasing the number of readers would not only bring in more from more subscription fees but also would draw in more advertisers. Lorimer increased the size of the page, making it more hospitable for big pictures. He expanded the length of the magazine to 24 pages (and suggested that it would soon grow to 32). He gambled much of the future of the magazine on pictures.

While this new content increased the cost of producing the Post, it also attracted thousands — eventually millions — of subscribers and made the Post the ideal forum for America’s new manufacturing industry, which was looking for ways to market everything from soap to cars. The Post rapidly outdistanced all of its competitors as a way to connect advertisers with consumers. Advertising revenues subsidized the 5 cent cover price and enabled the Post to commission brilliant illustrations for each issue.

People said Lorimer accomplished for the American magazine what Henry Ford did for the automobile.

A Magazine Renaissance

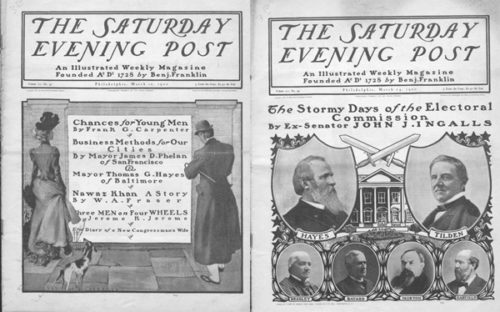

At the end of the 19th century, these three developments led to the Post’s renaissance, but the transformation wasn’t instantaneous. During the transition, the magazine sometimes offered hybrid covers that were half illustration, half table of contents.

But popular opinion became clear and there was no turning back. The cover pictures on the Post became an institution. Not only did cover artists propose topics and locations for Post covers, but readers would write in. The Post’s editorial staff would come back from their vacations or business travel with lists of sights they’d seen that might make a good cover. Hollywood studios would contact the Post to get the names of fetching models who appeared on Post covers. Everyone wanted to participate in the process, and that helped create the momentum that would serve the Post cover well for the next several decades.

The Enduring Appeal of Norman Rockwell

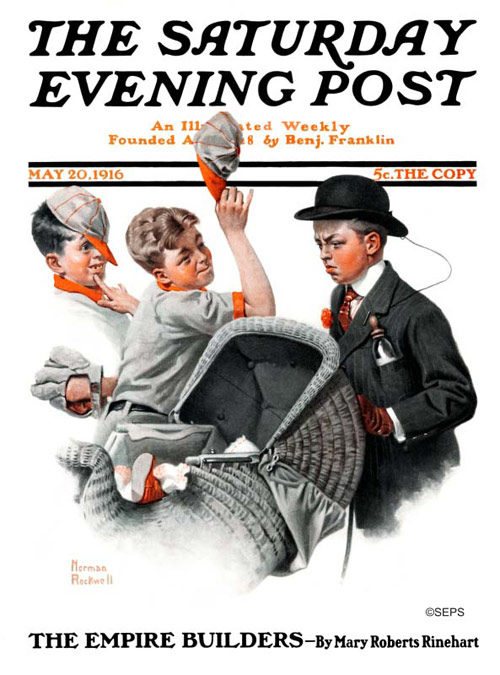

Readers looked forward to seeing the next Post cover illustration from such well-known artists as Andrew Wyeth, J.C. Leyendecker, and George Hughes. But of course, one can’t talk about The Saturday Evening Post’s history, and particularly its covers, without talking about the great Norman Rockwell.

In 1916, at age 22, Rockwell received his first commission for a cover of The Saturday Evening Post, beginning a 47-year relationship that produced 322 original cover illustrations.

Rockwell’s illustrations thrived in popularity, growing out from basic themes of a simpler time. His art looked up to an ideal: the perfect everyday lives Americans wished they could live. Illustrations of children fishing, playing, at the doctor’s office, getting a soda, and walking the streets enjoying summer all connected to the sensibilities of the time. His work elevated The Saturday Evening Post’s popularity, helping raise its subscription base to 6,900,000 nationwide by 1960.

Though illustration as a popular medium fell into decline, Rockwell’s popularity persisted, and he maintained a working relationship with the magazine throughout the 1960s.

Today, Rockwell’s works are highly coveted and can be viewed in private collections and museums around the country. Most famously, The Norman Rockwell Museum at Stockbridge, Massachusetts, holds a wealth of his work, and directors George Lucas and Steven Spielberg are avid collector’s of Rockwell’s work.

Life after Lorimer

Lorimer retired from the Post in 1936. He had felt increasingly out of touch in a country that had elected Franklin D. Roosevelt and could not reconcile himself to the New Deal.

The editorship was awarded to Wesley Stout, and then to Ben Hibbs, who joined the Post in 1942 and edited it for another 20 years, overseeing the magazine’s peak circulation of nearly 7 million in 1960.

William Emerson took over as editor in 1963 and remained until 1969. During that time, the Post struggled to retain its old popularity. Many factors were involved in its dwindling readership, including the rise of television and a new generation of magazines that appeared more contemporary.

It also seemed that the Post was doing everything it could to shoot itself in the foot. Managing editor Otto Friedrich was said to be out of touch and reluctant to act. An editor attacked Republican candidate Barry Goldwater so vehemently that the Post lost $10 million in advertising. And finally, the loss of a major libel suit (Curtis Publishing vs. Butts in 1967) saw the magazine paying more than $750,000 to the plaintiffs.

In 1968, Martin Ackerman, a specialist in troubled firms, became president of Curtis after lending it $5 million. Although at first he said there were no plans to shut down the magazine, he soon halved its circulation, purportedly in an attempt to increase the quality of the audience.

In 1969, The Saturday Evening Post suspended publication. In seven years, the company had endured five presidents and four editors and was $67 million in debt. It had approached CBS, Ford, Doubleday, and several other companies, but no one wanted a debt-riddled magazine with dwindling circulation.

That is, until Indianapolis industrialist Beurt SerVaas became interested. What he really wanted was the Post’s little sister, the children’s magazine Jack and Jill. SerVaas bought the magazine and moved the operation to Indianapolis, where his wife, Cory, ran it.

Transition and Rebirth

The Saturday Evening Post’s revival was due in great part to the continuing affection Americans felt for the magazine and to Beurt SerVaas’s business savvy and determination. After SerVaas bought the magazine and restarted the printing presses, the Post’s initial run of 500,000 copies sold out immediately; they reprinted 180,000 more and sold those as well.

At the time, SerVaas was known as an entrepreneur who specialized in turning around troubled companies. His life before the Post was as complex and varied as the man himself.

As a student, he hitchhiked to Mexico to learn Spanish. As America was entering World War II, he was graduating from Indiana University with degrees in chemistry, history, and Spanish. He was soon recruited into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner to the CIA, where he was sent on missions in China. There he helped the Chinese resistance against Japanese invaders and met with such historical figures as Ho Chi Minh, Chiang Kai-shek, and Mao Zedong.

After World War II, SerVaas ran a fledgling electronics company and then took on the task of revitalizing a silver-plating business. He married Cory Jane Synhorat, and together they marketed Cory’s invention that made it easier to sew aprons. The business was very successful.

The Saturday Evening Post was not SerVaas’s first foray into turning around magazines. Before buying the Post, he had also revived Trap and Field and Child Life.

In 1969, he learned of the troubles at Curtis Publishing. When he purchased Curtis, he not only got The Saturday Evening Post, but also Holiday and Jack and Jill magazines as part of the bargain.

SerVaas quickly sold off Curtis’s forests, paper mills, circulation department, and book company to focus on the magazine business.

The Post was initially revived as a quarterly publication that sold for $1. It retained its 11 x 13 inch size and revived the masthead of the 1920s and ’30s, the years when the Post became an American institution.

The very first issue brought back famed celebrity interviewer Pete Martin to interview Ali McGraw, commissioned William Hazlitt Upson to write another Alexander Botts story, and followed up on former Post boys (the young boys —and some girls — who sold the Post).

In the first issue, the editors wrote, “The goal of its revival is to re-establish the greatness and the simple grandeur that were its distinction over so many magnificent years.”

When Norman Rockwell announced on national television that he would be illustrating for the magazine again, subscriptions rose sharply, quickly reaching 350,000.

In 1982, the Post was purchased from Curtis Publishing by the Benjamin Franklin Literary Society, which was founded by Cory SerVaas. The Post beccame a non-profit entity that would focus on Cory’s passions: health, medicine, and volunteering.

In 2013, in another reinvention, the magazine returned to its original philosophy: celebrating America, past, present, and future. Since then, the Post has focused on the elements that have always made it popular: good story telling, fiction, art, and history. Today, it publishes a print magazine six times a year and is also vastly expanding its online offerings to include videos, podcasts, and the complete magazine archive.

Everyone loves a good story, and for nearly 200 years The Saturday Evening Post has told America’s story in real time. We hope you’ll join us as we continue to reflect on the narratives that make our country what it is today.