Fiddling with the Clock but Leaving the Calendar Alone

This weekend, as we set our clocks back to Daylight Standard Time, many of us may ask ourselves, “Why, exactly, do we do this?”

Or, “Who decides when we change our clocks?”

Or, “Why is it called ‘Standard Time’ when it’s only in effect for four months out of twelve?”

The official reason for setting clocks back one hour is to save energy. By moving our daily activity toward the hours of maximum sunlight, we use less energy for lighting. Or so the argument goes. But one study has found energy savings are far lower than expected. And another found energy consumption actually increased with Daylight Saving Time.

Despite the questionable benefits of Daylight Saving Time (DST), America seems resigned to disrupting its daily schedule twice a year.

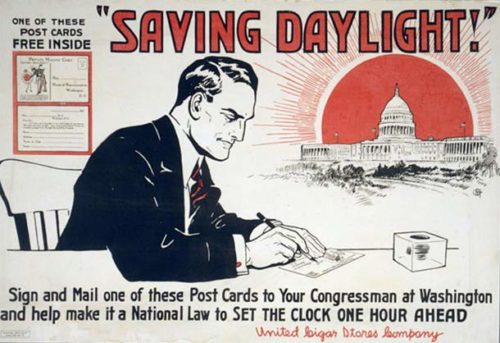

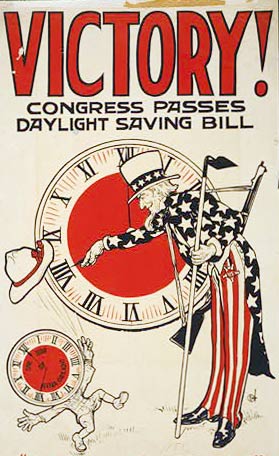

Certainly Congress appears to like the idea. Since making DST a permanent, nationwide standard in 1966, legislators have steadily expanded its yearly length from 27 weeks to 34 weeks.

Given Congress’ enthusiasm for fiddling with the clock, it’s surprising that legislators haven’t tried reforming the calendar. Congress has already reassigned two presidential birthdays to a more convenient time. Perhaps they might want to consider bringing order to our 263-year-old Gregorian calendar with the 13-month calendar.

At present, our year is divided into irregular months or 30, 31, and 28 days. In contrast, the international fixed calendar would neatly divide the year into 13 months, all beginning on a Sunday and ending on a Saturday, and all having 28 days. The extra month, called Sol, would be sandwiched between June and July. The only variations would be December 29, a holiday at the end of the year called not, as logic would have it, Sunday, but instead Year Day and a June 29, known as Leap Day, every four years.

Back in the 1920s, the idea drew the support of George Eastman, founder of the Eastman Kodak Company. Having made a fortune in the early photographic industry, Eastman was hardly an impractical dreamer. He strongly supported the 13-month calendar and believed, as he wrote in a 1928 Post article, it would soon become the international standard “because the world moves inevitably toward the practical.”

The reformed calendar had several benefits, he claimed:

- It would standardize the schedules for debt and interest payments.

- It would let business owners accurately compare monthly revenues between years.

- Scheduling employees would be easier with the same number of work days and weekends in each month.

- Holidays could be moved to Mondays so that workers could enjoy two-day weekends.

This last benefit shows how dated the idea is. Most employees in 1928 worked six-day weeks. The 40-hour workweek only became a standard practice with the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

Technology has achieved some of the other benefits. Computers enable businesses to set schedules and manipulate data between months of uneven length.

The 13-month calendar was part of a trend toward efficiency that arose in the 1910s, the same trend that brought standardized time to the country. But 20th-century Americans didn’t want too much efficiency. They balked at losing variety and spontaneity. Which is probably why they never embraced the highly uniform 13-month calendar. Among other things, it would set their birthday to the same day of the week every year. It was, perhaps, too predictable. We seem to like some variation in out time keeping.

Which, perhaps, is why we willingly change our clocks twice every year.