The 14th Amendment Settled, and Started, Citizenship Battles 150 Years Ago

Amending the United States Constitution remains a monumental act, even if such modifications were always intended from the moment that the document was designed. While every amendment has faced challenge and debate, few groups have inspired as much controversy and litigation as the so-called Reconstruction Amendments. Amendments 13, 14, and 15 came in the aftermath of the Civil War, and their implications and legacy have reached further than many expected. The ratification of the 14th Amendment, covering citizenship, due process and much more, and its certification were proclaimed by Secretary of State William H. Seward 150 years ago on July 28th.

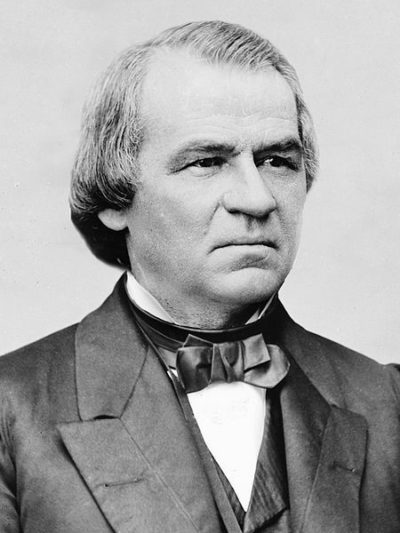

The birth of the 14th Amendment came out of a complicated dance of conflicting political priorities. The sudden influx of “new” citizens created by the 13th Amendment (which ended slavery) threatened to upend the power balance in the south in the House of Representatives because a larger population requires more representatives. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 passed Congress, guaranteeing citizenship to every person born in the United States regardless of race, color or “prior condition of servitude.” Andrew Johnson would veto the bill twice, but Congress overrode him, turning it into law. However, not everyone in Congress was satisfied that this solution should lie outside the Constitution.

More than 70 proposals for a new amendment to address citizenship were written. Ultimately, after much debate and a number of counter-proposals, modifications, and compromises, the text of the 14th Amendment was codified and passed. Many in Congress were disappointed that the bill didn’t go so far as to address voting rights for former slaves; fortunately, that would be covered less than two years later with the ratification of the 15th Amendment.

The Amendment contains five sections, and they cover an incredible amount of legal ground. Section 1 covers birthright citizenship, the right to due process, and equal protection for citizens under the law. Section 2 acknowledges that everyone (well, males at any rate) was a “whole person” rather than the three-fifths allotted to black Americans previously; it also establishes some voting protections. The third section works to prevent previous rebels (see: military and elected officials of the Confederacy) from holding office, military rank, or civil service jobs unless they would receive a 2/3 vote of Congress giving them approval. Section 4 more or less tells the South that they’re stuck with their debts in the wake of the war; if they accrued debt from borrowing to fund the unsuccessful rebellion or losses from having their slaves freed, that was, legally speaking, too bad. The final section simply affirms the authority of Congress to enforce the Amendment with legislation.

Since its ratification, the Amendment has figured into elements of at least 90 Supreme Court cases, due in part to the large ground in covers. Some of the cases rank among the most important in U.S. history. The Amendment played a part in the school segregation breakthrough of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 due to the Equal Protection clause; that same clause was involved in the election-deciding Bush v. Gore in 2000. Issues of Substantive Due Process were raised by Roe v. Wade in 1973 when the court ruled in part that the right to privacy included a woman’s decision to have an abortion. Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015 also invoked both Substantive Due Process and Equal Protection on the way to a decision that legalized same-sex marriage.

Today, the issues surrounding the 14th Amendment continue to fuel considerable public and legal debate. As recently as July 19th, Johns Hopkins University historian and author of Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America Martha S. Jones spoke to The New York Times on how the protections of the Amendment figure into the current controversy surrounding immigration. In response to a question about whether or not the lessons of history can solve current problems, Jones says, “I don’t think history is a blueprint. It can’t be. There’s too much that’s particular to our own time and place. But I do think the debate about birthright citizenship is here, and you can’t be well equipped for it unless you are familiar with where it begins.”