Loving and Hating Walt Whitman

In its earlier years, it seems this publication couldn’t make up its mind about Walt Whitman and his divisive poetry. The poet — who would be 200 years old today — turned heads around the world with his humanist classic Leaves of Grass. The Saturday Evening Post published a criticism of the author deemed “honest, downright writing” in 1860: “He has strength, he has beauty, but he has no soul. Intellect, I grant, wide in its scope, and powerful in its grasp. Yet with all this, I doubt if, when the Judgment-Day comes, Walt Whitman’s name will be called. He certainly has not soul enough to be saved. I hardly think he has enough to be damned.”

The harsh words came from Calvin Beach, a reviewer whose 200th birthday is likely to pass by unnoticed.

In 1865, however, the daguerreotypist and Post editor William Douglas O’Connor penned a pamphlet to show the world how much soul his friend Walt Whitman actually had. O’Connor’s The Good Gray Poet heaped praise — at times unnecessarily — upon Whitman, calling him “a man of striking masculine beauty — a poet — powerful and venerable in appearance; large, calm, superbly formed; oftenest clad in the careless, rough, and always picturesque costume of the common people.” O’Connor’s vindication of Whitman came after the latter was dismissed from a job in the Department of the Interior. It was the last straw of many years of Whitman-bashing, with many academic circles and critics having described his Leaves as indecent, obscene trash, and Whitman himself as a filthy free lover and possibly a homosexual.

The Post kept up its opprobrium in 1873, musing about Whitman’s tendency to leave out the resolution of a thought in his poetry: “His stops make him popular. The more he stops the more popular he becomes. If he should stop altogether the public would give him a monument, and perhaps a horse.” Aptly, The Country Gentleman came around in 1897 with “A Defense of Walt Whitman.” While the agriculture publication wasn’t prepared to go to bat for the whole scope of Whitman’s worldview, the article admits that the poet shines from time to time with powerful language: “The healthy, vigorous and intense personality of the man seems to have entered his work and inspired it with a moral [we might better have said a tonic] force; he feels called on to instruct, and his lesson is sympathy.”

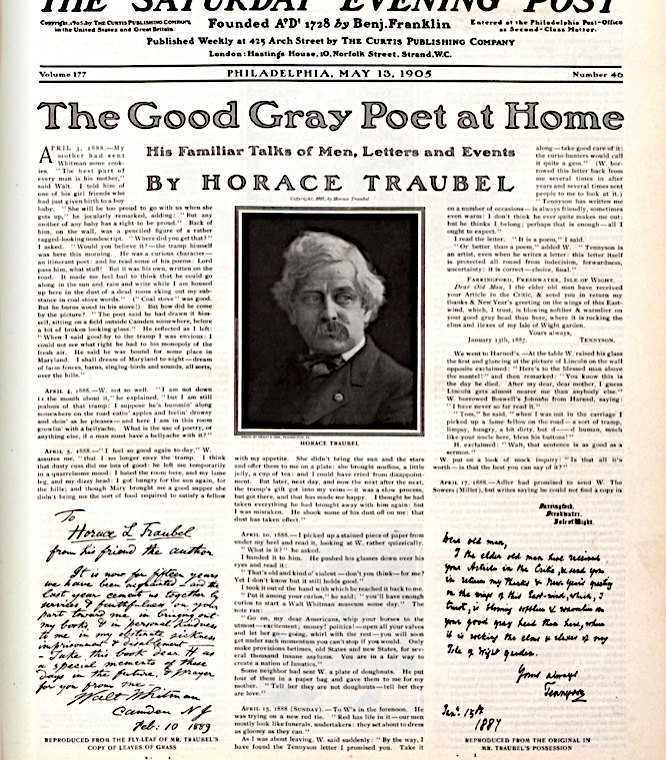

That a magazine published for rural America would support Whitman is, perhaps, unsurprising, but the Post finally paid its respects in 1905. Horace Traubel, a socialist poet and essayist, spent time with Whitman in the years before his death, compiling letters, conversations, and anecdotes in his book With Walt Whitman in Camden. His visits with Whitman in April 1888 were featured in the Post as “The Good Gray Poet at Home” in two parts.

In his final years, Whitman displayed humility, clarity of purpose, and stark honesty about his place amongst his peers. Traubel captures the aging poet’s simultaneously courageous and humble self-expression in his report, as Whitman discusses topics ranging from American morality to deserts.

The good gray poet on one of his greatest supporters, Ralph Waldo Emerson:

We were not much for repartee, or sallies, or what people ordinarily call humor, but we got along together beautifully — the atmosphere was always sweet, I don’t mind saying it, both on Emerson’s side and mine: we had no friction—there was no kind of fight in us for each other — we were like two Quakers together. Dear Emerson! I doubt if the literary classes which have taken to coddling him have ally right to their god. He belonged to us — yes, to us — rather than to them.

On Henry David Thoreau:

Thoreau’s great fault was disdain — disdain of men (for Tom, Dick and Harry): inability to appreciate the average life — even the exceptional life. It seemed to me a want of imagination. He couldn’t put his life into any other life — realize why one man was so and another man was not so: was impatient with other people on the street, and so forth. We had a hot discussion about it — it was a bitter difference: it was rather a surprise to me to meet in Thoreau such a very aggravated case of superciliousness. It was egotistic — not taking that word in its worst sense.

On America:

Someone cried out there at Gloucester: ’You’re d[amne]d tolerant, Walt!’ Am I? Call it toleration, if you choose. I only call it common-sense — philosophy. I am extreme? Perhaps. But then it is with America as it is with Nature: I believe our institutions can digest, absorb all elements, good or bad, godlike or devilish, that come along: it seems impossible for Nature to fail to make good in the processes peculiar to her: in the same way, it is impossible for America to fail to turn the worst luck into best — curses into blessings.

“I no doubt deserved my enemies, but I don’t believe I deserved my friends,” Whitman remarks, acknowledging the slings and arrows he faced over the years with a calm resolve. For a writer who spent decades perfecting his deeply philosophical and soul-searching volume of poetry, Whitman speaks of himself and his work with almost as much derision as his critics. He doesn’t take himself too seriously, and perhaps that is the key to his steadfastness in the face of truly abhorrent press (a review of Leaves in the Saturday Press suggested that he commit suicide).

“A man makes a pair of shoes—the best—he expects nothing of it,” Whitman says, “he knows they will wear out: that’s the end of the good shoe, the good man. Any kind of a scribbler writes any kind of a poem and expects it to last forever. Yet the poems wear out, too—often faster than the shoes. I don’t know but in the long run almost as many shoes as poems last out the experience.” More than 150 years after publication, “Song of Myself” is still assigned reading in schools, and the good gray poet will outlast his fiercest detractors.

Featured Image: “Whitman at about fifty” by Methuen & Co., 1905.