The Rocky Horror Picture Show: Still Doing the Time Warp 45 Years Later

Having performed in both the touring and London productions of Hair in the early 1970s, Richard O’Brien combined his love of science fiction, horror, and comic books with his stage background into writing the musical The Rocky Horror Show. The play rapidly grew in popularity, moving from theatre to bigger theatre in England. When the opportunity came to take the tale to the screen in 1975, little did anyone involved know that their film would still be playing around the world 45 years later. I would like, if I may, to take you on a strange journey . . . this is the story of The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

O’Brien was born in England in 1942 and moved to New Zealand with his family in the 1950s. After college, he went back to England in 1964 and began working on stage and in film. O’Brien played both an Apostle and Leper in the London production of Jesus Christ Superstar; the director who cast him was Jim Sharman. Sharman would cast him again, and O’Brien shared his idea for They Came from Denton High, a musical send-up of the things that he loved, like 1950s science-fiction movies. Sharman came on board as director and gave O’Brien the idea for a new name: The Rocky Horror Show. In June 1973, the show kicked off at London’s Theatre Upstairs; it quickly became a hit, moving to bigger venues until making it to the U.K’s equivalent of Broadway, the West End.

Lou Adler was already a big name in American music when he saw Rocky in London. Adler had produced Carole King’s Tapestry, the Monterey Pop Festival, and six hits for The Mamas and The Papas, including “California Dreamin’.” He bought the U.S. theatrical rights, taking the show to the Roxy in L.A. Soon after, Michael White, who had produced the London shows, Adler, O’Brien, and Sharman were collaborating on a film version. Adler and White produced with Sharman directing and co-writing the screen adaptation with O’Brien.

The trailer for The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Uploaded to YouTube by 20th Century Studios)

In terms of casting, several members of the London cast made the jump to screen. Tim Curry (Dr. Frank-N-Furter), O’Brien (Riff Raff), Patricia Quinn (Magenta), and “Little Nell” Campbell (Columbia) had all been in productions in England. The ostensible lead roles of Brad and Janet were trickier, as studio 20th Century Fox wanted American actors in the parts; those ended up being filled by Barry Bostwick and Susan Sarandon. Charles Gray, a two-time Bond villain, played the criminologist/narrator and Jonathan Adams was cast as Dr. Scott. Marvin Lee Aday, better known as Meat Loaf, was a veteran of Broadway’s Hair and had played Eddie in the L.A. cast; he reprised Eddie for the movie, two years before the release of his massively successful Bat Out of Hell album. Background character Betty Munroe (whose wedding Brad and Janet attend early in the film) was played by Hilary Labow, which was the screen name of Hilary Farr, known today as the designer on the long-running renovation series Love It or List It.

Much of the Gothy, classic horror mood of the film came from the location at Oakley Court. The estate had been used in several Hammer Studios films, including The Brides of Dracula and The Plague of the Zombies. In Sharman’s direction, you can occasionally note some of the same wide angles and sudden zooms prevalent in Hammer features, which were meant to echo styles prevalent in the genre. Richard Hartley produced the soundtrack and handled musical arrangements on the songs that O’Brien had written. The soundtrack lists 21 official numbers, although “Once in a While” came from a deleted scene and “Super Heroes” was only seen in the U.K. until the eventual video release.

A portion of “Sweet Transvestite” from The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

The film opened 45 years ago this week in London, with the U.S. opening a few weeks later. It was not an immediate success. Outside of L.A., it was quickly pulled from theatres. Tim Deegan, a Fox executive, suggested an alternative strategy; figuring that the film might do well on the midnight circuit, as John Waters films had, Deegan got the ball rolling in New York. The Waverly Theater became ground zero for a cult phenomenon, fostering audience participation in the form of recited remarks and props. Audience members began coming to the show in costume, and screenings started to have live casts that would act out the film as it ran on the screen. Within a couple of years, the movie had become a legit cult sensation and defined the notion of the “Midnight Movie.”

The movie has actually never closed, making it the longest-running release in the history of film. Some fans and film history buffs were concerned about the status of the film when the Walt Disney Company finished its acquisition of 20th Century Fox in 2019. However, even though Disney “vaulted” a number of Fox titles, they were conscious of Rocky’s status and fandom and decided to keep it in release so that the screenings would go on.

A portion of “Hot Patootie Bless My Soul” from The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

So, just what has made it endure? At the top, the music is insanely catchy, particularly “The Time Warp.” The notion of attending a movie as a sort of costume party is fun, and the props and interaction make it a shared experience that you can join in over and over. But a deeper undercurrent is that Rocky Horror celebrates the outsider. It’s been embraced by the LGBTQ+ community, theater kids, punks, goths, comic book fans, horror and science fiction fans who get the in-jokes, and more, all of whom find connection to the film. Its influence has reverberated through the years, turning up in sitcoms like The Drew Carey Show or a 2010 episode of Glee or in films like The Perks of Being a Wallflower or Fox’s 2016 TV remake. It has endured for four-and-a-half decades, and there’s no sign that it will go away anytime soon. One supposes that it’s comforting to know that as much as some cult phenoms come and go, there will always be a light over at the Frankenstein place.

Featured image: UA Cinema Merced. The Rocky Horror Picture Show, opening night, January of 1978. (Photo by Robin Adams, General Manager, UA Cinema, Merced California, 1978. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.; Wikimedia Commons)

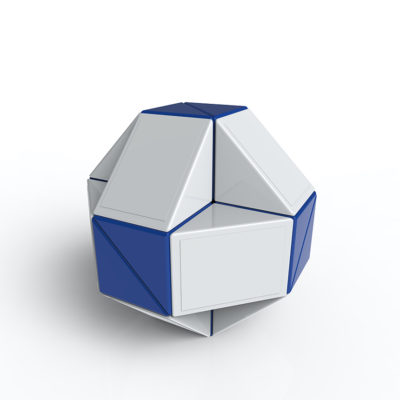

The Rubik’s Cube Turns (and Turns and Turns) 40

How do you build the perfect puzzle? In the case of one Ernő Rubik, it involved rubber bands, wood, and inspiration. In 1975, he applied for a patent for his “Magic Cube,” but it really broke through when the Ideal Toy Company took it international five years later. Hungary might have known the fiendishly clever device since 1977, but for the rest of the world, this is the day that the Rubik’s Cube turns 40.

(Babak Mansouri [Public domain])

Rubik’s Cube commericals. (Uploaded to YouTube by Rubik’s)

Businessman Tibor Laczi took the Cube to the Nuremberg Toy Fair in 1979 to try to get the puzzle some attention outside of Hungary. It worked; the Cube caught the eye of Ideal Toys, who acquired the distribution rights and re-named the puzzle the Rubik’s Cube. The toy made its international debut 40 years ago today as it began hitting the Toy Fairs in London, Paris, Nuremberg, and New York. The Cube hit stores in America in May of 1980, and sales took off once TV advertising got behind the toy. 1981 was truly the Year of the Cube; in addition to millions of units being sold in the U.S., no less than three books about solving the Cube were bestsellers. The Cube was also named Toy of the Year in Germany, France, the UK, and the U.S. in 1980, and in Italy, Finland, and Sweden in 1981. One of the side effects of the craze was “speedcubing,” which was simply the practice of solving a Cube really, really fast. It sparked competitions everywhere from college campuses to pop culture conventions.

Rubik went on to create other popular mechanical puzzles, including the Rubik’s Magic and the Rubik’s Snake. With the advent of social media and video sharing platforms, the Cube and similar toys got a renewed boost in popularity; that newfound visibility also prompted the return of speedcubing The inventor himself has spent the last several years touring an exhibition called Beyond Rubik’s Cube, a STEM focused program. Rubik is something of a hero in his home country, having been honored numerous times for his contributions to culture, including the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Stephen, which is the highest award that a Hungarian citizen can receive.

40 years later, the continued popularity and iconic nature of the Rubik’s Cube speaks volumes about the mind of its creator. It’s a fiendishly simple idea built on interesting principles of mechanics and design. It has both captivated and frustrated millions and maintains a reputation as one of the great toys of all time. No one can say for sure what the perfect puzzle is, but it’s possible that Ernő Rubik came closer than anyone to solving it.

Featured image: dnd_project / Shutterstock

The Week of Peak Disco

Can you pinpoint the exact moment that a musical movement peaks? It’s easy to define music to nonspecific eras: you have the British Invasion, the early 1990s Alternative Explosion, and so on. However, the unassailable peak of disco happened the week of July 21, 1979, when the top six songs in the U.S. (and seven in the Top Ten) were classified as disco tunes. Over the following few weeks, every trace of the style would vanish from the charts. This is the story of a genre’s rise, greatest moment of triumph, and fall.

An exact date for the creation of disco is impossible to pin down, but we can trace its development from earlier decades to the 1970s. One significant step in the genre’s development was the ongoing slate of private parties hosted by New York DJ David Mancuso at his home starting in 1970. Mancuso’s approach was copied by others; as his own “The Loft” became the epicenter of a new dance culture, it spread into other private parties and clubs. The Loft was notable for the blended audiences that it attracted; no barriers were placed on ethnicity or sexuality, and the music had to be danceable and generally celebratory.

The sound of disco came from a variety of places. Motown R&B played a part, as did the soul stylings of groups from cities like Philadelphia, like The O’Jays and The Stylistics. Producers like Tom Moulton pushed the record format when it came to dance, extending single lengths by using 12” vinyl and innovating the remix approach that added or enhanced elements of songs. The psychedelic soul sound associated with later Temptations records and the funk of George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic added other ingredients to the brew.

The O’Jays perform “Love Train” (Uploaded to YouTube by the O’Jays)

From a cultural standpoint, the shift from the 1960s to the 1970s opened the door for new things. As the counterculture movement died off and Vietnam continued, economic uncertainty plagued the country. The ongoing social turmoil became a crucible for new and reinvented forms of music, including the evolution of heavy metal, punk, hip-hop, and disco. In the book Beautiful Things in Popular Culture, Simon Frith said, “The driving force of the New York underground dance scene in which disco was forged was not simply that city’s complex ethnic and sexual culture, but also a 1960s notion of community, pleasure and generosity that can only be described as hippie. The best disco music contained within it a remarkably powerful sense of collective euphoria.” Soon dance records that broke in the clubs found success on the radio and in record stores, adding some early fuel to the movement.

“Rock the Boat” by The Hues Corporation (Uploaded to YouTube by The Hues Corporation / RCA Victor)

On the charts, a number of songs that could arguably be classified as disco emerged as hits in the very early 1970s. Among these were “Love Train” by The O’Jays (1972) and “Love’s Theme” by Barry White’s The Love Unlimited Orchestra (1974). When “Rock the Boat” by The Hues Corporation hit #1 in May of 1974, many declared it to be the first disco #1, though others held up “Love’s Theme” (which topped the charts in February) as the first. Regardless of which was “first,” it was evident that the style had a place on the charts and was primed to grow. Carl Douglas’s “Kung-Fu Fighting” and George McRae’s “Rock Your Baby” also hit #1, with “Rock” having the added distinction of being the first disco #1 in the U.K. The success of disco rolled into 1975, with landmark tracks like Van McCoy’s “The Hustle” and the commercial breakthroughs of Donna Summer and KC and The Sunshine Band.

“Night Fever” by The Bee Gees (Uploaded to YouTube by beegees)

The popular acceptance of the form took it into more mainstream clubs and into film and television. A 1976 New York magazine article inspired the disco-driven 1977 film Saturday Night Fever. The already popular Bee Gees had turned their attention to more dance-oriented sounds by 1975, and the trio had created hits like “Jive Talkin’” and “You Should Be Dancing” (1976). The Bee Gees agreed to craft songs for the film; those tunes, as well as songs they wrote for others and contributions from different acts, would form one of the best-selling soundtracks in history. The success of the Oscar-nominated movie and the soundtrack (over 16 million albums sold) remarkably elevated the profile of the genre to even greater heights.

Between 1977 and 1980, roughly 22 songs that fit into the disco genre hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100. These included obvious numbers like “I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor and “Dancing Queen” by Abba, as well as critically acclaimed pieces “Don’t Leave Me This Way” by Thelma Houston (a cover of a Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes song, Houston’s version won a Grammy for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance in 1977).

“Don’t Leave Me This Way” by Thelma Houston (Uploaded to YouTube by Thelma Houston)

Despite the popularity of the form, there were definitely dissenters. One of them was Steve Dahl, a rock DJ who lost his job at Chicago’s WDAI when the station switched from a rock format to disco. Dahl was hired by WLUP and worked hard to stir anti-disco backlash. After promoting a few events, Dahl participated in a promotion at Comiskey Park, home of the White Sox. Disco Demolition Night on July 12, 1979, encouraged fans to bring disco records to the double-header between the Sox and Tigers where the discs would be blown-up in center field. The event got out of hand early when fans that couldn’t get into the sold-out affair broke into the stadium anyway. Beer, firecrackers, and albums rained on the field throughout the first game. After the crate of records was detonated between contests, thousands of fans rushed the field. Police were called, and eventually the White Sox had to forfeit the game (it’s the last American League behavior-forfeit on record). While many, like Dahl, dismissed the circumstances of the event as harmless fun gone out of hand, others like Rolling Stone writer Dave Marsh expressed that a lot of the hostility toward disco included bigotry toward black, Latino, and gay artists and fans.

“Hot Stuff” by Donna Summer (Uploaded to YouTube by Donna Summer Universal Music Group

Despite the anti-disco sentiment, a few days after the Comiskey Park incident, the Billboard Charts reflected the week of peak disco. Seven of the Top Ten were disco tracks, including: “Bad Girls” by Donna Summer (#1); “Ring My Bell” by Anita Ward (#2); “Hot Stuff” by Summer (#3); “Good Times” by Chic (#4); “Makin’ It” by David Naughton (#5); “Boogie Wonderland” by Earth, Wind, & Fire with The Emotions (#6); and “Shine A Little Love” by Electric Light Orchestra (#8). ELO, like Blondie, weren’t a traditional disco band, but did release songs that employed the sound. Despite this high, disco was about to hit its inglorious low.

“My Sharona” by The Knack (Uploaded to YouTube by The Knack / Universal Music Group)

On August 25, “My Sharona” by The Knack began a six-week run at #1. Critics typically lump The Knack in with “new wave” rock acts that also included multi-genre stylists Blondie, Elvis Costello, and others. Disco would continue to dot the charts for a while, but the cultural backlash caused many artists to simply relabel themselves as “dance.”

When MTV kicked off in 1981, it effectively killed disco for good in two ways. The first is the unfortunate reality that that the network played very little in the way of black artists in its early days. The second is that the channel embraced bands that were already making videos or working overseas (where the “video clip” format was already popular), resulting in a massive push for predominantly white, new-wave-related bands and English bands. Everyone seems to know that the first video played on MTV was “Video Killed the Radio Star” by The Buggles, but the next nine were from Pat Benatar, Rod Stewart, The Who, Ph.D., Cliff Richard, The Pretenders, Todd Rundgren, REO Speedwagon, and Styx. Black artists wouldn’t break through on the channel until the massive success of Michael Jackson and Prince in the following two years forced the network to catch up.

Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” enjoys ongoing life in other media and sporting arenas. (Uploaded to YouTube by Gloria Gaynor / The Orchard Enterprises)

Today, disco culture is a staple of films and TV, as seen in everything from Boogie Nights to Pose to The Martian (Matt Damon’s character may have hated it, but Jessica Chastain’s loved it). The musical style has adapted and integrated into a variety of genres, including EDM and hip-hop, where sampled hooks are still regularly mined from disco classics. Package tours of disco artists continue to circulate. The influence is felt in a number of popular songs of the past few years, among which are Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky” (which features Nile Rodgers of Chic), “Uptown Funk” by Bruno Mars, and “Can’t Feel My Face” by the Weeknd. Disco may never have a proper, world-dominating comeback, but it never truly went away. It’s fair to say that no matter how you try to kill it, it will survive.

The Family Road Trip

If there was ever a time Americans needed a vacation, it was the 1970s. Nearly everyone had a good reason to pack up their station wagon or VW minibus and leave it all behind. The gloomy conclusion to the war in Vietnam had sent morale plummeting, while unemployment and inflation skyrocketed and remained elevated so long that economists had to coin a whole new term for the phenomenon: stagflation.

The pressure of making ends meet also helped push the traditional nuclear family into meltdown. The number of divorces filed in 1975 doubled that of a decade earlier. All things considered, it isn’t surprising that many people, including my parents, decided the best plan was simply to sit out as much of the ’70s as possible at some distant beach, historic battlefield, or theme park.

Despite the flagging economy, Americans continued taking vacations throughout the ’70s in record numbers, if only for a couple of weeks each year. In fact, 80 percent of working Americans took vacations in 1970, compared to just 60 percent two decades earlier. As a result, attendance at national parks, historic sites, and other attractions surged 20 to 30 percent every year until 1976.

To reach these far-off places, my family, like most others, traveled by car. It wasn’t that we enjoyed spending endless hours imprisoned together in a velour-upholstered cell, squabbling over radio stations. It was that we had no other choice.

Air travel had always been too expensive for anyone not named Rockefeller or traveling on the company dime, much less a pair of middle-class parents taking four kids to the beach. Adjusted for inflation, a domestic plane ticket in the ’70s cost two to three times the price of the same ticket today. Given the cost, it shouldn’t be too surprising — and yet still is — that as late as 1975, four in five Americans had never traveled by plane. Not for a weekend getaway to Las Vegas, not to head off to college, not for a once-in-a-lifetime honeymoon in Paris. Never.

Although ordinary joes couldn’t afford a plane ticket, nearly every family could afford a car, often two. If there was one thing America was very good at, it was producing automobiles. Following World War II, American car factories needed only to do some quick retooling to go from churning out airplanes and tanks to cranking out cars faster than ever. And thanks to a booming economy, Americans could afford to buy all those shiny new cars as fast as they rolled off assembly lines. During the 1970s alone, Americans logged 14.4 trillion highway miles.

My family alone was responsible for approximately 1 trillion of the miles logged by travelers in the ’70s. At least that’s how it seemed to me: As the youngest of four kids, I was the one relegated to the backseat, rear window shelf, or rear cargo compartment of a series of fine American automobiles purchased by my father over the course of the decade. Together, we toured the country (well, half of it anyway — we rarely traveled west of the Mississippi) in week-long journeys taken two and sometimes three times a year.

My father was one of those people born with no “stop” gene. He always had to be on the go, always had to be doing something. Even if he was sitting still, his mind was always racing, thinking about the next item on his to-do list: his next sales call, his next round of golf, his next Rotary meeting, his next whatever.

In short, his disposition made him ill suited for 15- to 24-hour road trips. The advent of the 55 mph national maximum speed limit only exacerbated his restlessness. But what really aggravated my father was having to make stops he judged unnecessary — which is to say, any stop at all. If my dad had his way, we wouldn’t have ever stopped — not for meals, not to refill our gas tank, not even for potty breaks.

What really aggravated my father was having to make stops he judged unnecessary — which to say, any stop at all.

My dad couldn’t do much about our need to occasionally refuel — at least, beyond stretching every tankful of gas to its gauge-defying limit. But he could control how often we stopped for meals. His main strategy was to forget meals altogether. As lunchtime approached after a long morning’s drive, he’d click off the radio and announce, “Why don’t we all take a break for a while? Maybe you kids can get a little extra sleep. You’ll want to be rested for the beach tomorrow!” We’d settle into our corners to read magazines, click away on our electronic games, or just doze off, only to awaken hours later with rumbling stomachs.

Finally, one of us would say, “Dad, I’m hungry! When are we stopping to eat?”

“Oh, look at that,” he’d respond, playing dumb. “Did we miss lunch? Well, no point stopping now. We’d just ruin our appetites for dinner!” Then he’d ease into the passing lane just in case any exits appeared.

Though I have little knowledge of such things from personal experience, I’m told some families once even stopped for minutes — maybe an hour! — to enjoy freshly cooked meals — served on actual plates with silverware! — while out on the highways. In fact, one man built an empire preparing such meals for hungry travelers. His name was Howard Deering Johnson.

Johnson inherited his entrepreneurial spirit from his father, who owned a Boston cigar store and export business in the early 1920s. Unfortunately for Johnson, he also inherited the equivalent of more than $100,000 in debt when his father died and left him the foundering business. Quickly concluding that the cigar business might not be the best for striking it rich, Johnson decided to try his hand at another, buying a small drugstore and soda fountain in the Wollaston neighborhood of Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1925.

Business was brisk at the soda fountain, but competition was fierce. To help his business stand out, Johnson decided he needed to offer truly outstanding ice cream — like the kind made by a local pushcart vendor, an elderly German immigrant. Learning the man was contemplating retirement, Johnson paid the handsome sum of $300 for the vendor’s recipe. The secret, Johnson learned, was doubling the typical amount of butterfat and using only natural ingredients. But for Johnson, even that wasn’t enough. He locked himself away in his basement and used a hand-cranked ice cream maker to create and perfect 28 different flavors, a number Johnson believed covered “every flavor in the world.”

Before long, customers were lining up for Johnson’s tantalizing array of frozen treats. He quickly opened another stand at a local beach — it served as many as 14,000 cones in a single day! Leveraging the popularity of his ice cream, Johnson began serving freshly grilled meals as well and soon opened a full-blown restaurant. Besides hamburgers, “frankforts” (as Howard Johnson called his hot dogs), chicken pot pies, and other staples, the menu also included another New England favorite: fried clams. Unlike other restaurants, which served whole clams, Howard Johnson’s prepared and fried only the meaty foot of each clam, calling them “clam strips.” The item became Howard Johnson’s signature dish.

However, just as Johnson was hoping to take advantage of his growing fame by opening another location, the stock market crash of 1929 intervened. Unable to find financing, Johnson hit on the idea of leasing his restaurant’s increasingly famous name and recipes to the owner of an existing restaurant. This location, on the tourist mecca of Cape Cod, also proved fabulously successful. Soon other restaurant owners were clamoring to borrow the Howard Johnson’s name and purchase his food. Howard Johnson had invented franchising.

It wasn’t long before Johnson purchased the exclusive rights to build restaurants in service plazas along the new Pennsylvania Turnpike, Ohio Turnpike, and New Jersey Turnpike. By the late 1970s, Howard Johnson’s controlled more than 1,000 restaurants (under several names) and 500 motor lodges, making it the largest hospitality chain in the world.

If you want to start a food fight, there’s no better way than to declare where to find the world’s best barbecue or proclaim who invented the first drive-through restaurant. In his book The American Drive-In: History and Folklore of the Drive-In Restaurant in American Car Culture, Michael Karl Witzel makes a strong argument that credit for both should go to Texas entrepreneur Jessie G. Kirby and his chain of roadside Pig Stands, the first of which opened along the Dallas–Fort Worth highway in 1921. Declaring “people in their cars are so lazy that they don’t want to get out of them to eat,” Kirby had a brainstorm to employ a fleet-footed staff of order takers. The carhops (so named because the tip-motivated servers would sprint out to hop up on an approaching automobile’s running board) would take food orders right through the customer’s car window. Billed as “America’s Motor Lunch,” the new system launched a craze.

Technically, Kirby’s idea qualified his Pig Stand only as America’s first drive-in restaurant. The first drive-through would come later, and once again Kirby’s Pig Stand would be the originator. In 1931, Pig Stand No. 21 in California simply sawed a window into the wall beside the grill, allowing customers to drive up alongside the building and collect their food directly from the cooks who prepared it. It was a classic example of eliminating the middleman.

And so ends the debate about who invented the drive-through window, right? Well, don’t go pulling off just yet. Other sources claim the idea was conceived by a young ginger-haired entrepreneur named Sheldon “Red” Chaney, who purchased a small gas station along Route 66 in Springfield, Missouri, in 1947. After spending 16 hours a day pumping gas and observing customers, Red concluded two things: one, he didn’t want to spend the rest of his life pumping gas, and two, people hate getting out of their cars.

Eating at McDonald’s fit our modest travel budget. After all, the restaurant was cheap, and, well, so was my dad — at least when it came to food.

The Chaneys decided to get out of the business of fueling cars and into the business of feeding motorists. Redecorating their station on a shoestring, Red and his wife Julia covered the dining room’s tables in red-checkered tablecloths and topped each with a button-spigot Coleman cooler and stack of paper cups so diners could dispense their own water. But the couple’s most radical idea was adding a small window in the building’s west wall, allowing drivers to pull up and order food right from their cars.

The drive-through window prompted cars to line up around the building. Eventually Red installed an intercom system so drivers could dictate orders before advancing to the window to collect their food. Voilà! Red’s Giant Hamburg became the first modern fast-food drive-through restaurant.

Though McDonald’s restaurants had been around since the 1940s, the chain didn’t introduce its first drive-through window until 1975. The McDonald’s store in Sierra Vista, Arizona, was located just down the road from the Fort Huachuca military base, making it a popular lunch stop for soldiers. But military rules at the time prohibited enlisted personnel from exiting civilian vehicles dressed in fatigues. To accommodate the soldiers, the franchisee installed a drive-through window. Soon, the only ones dealing with issues of fatigue were the fry cooks scrambling to fill orders, and other franchisees began lobbying McDonald’s headquarters for permission to add their own. By 1980, McDonald’s was collecting $6.2 billion from 6,200 stores. More than half of that cash would be handed over through drive-through windows.

My dad didn’t care how it had all happened. He was just happy it happened at all. Finally, he had a means to put an end to his family’s incessant — unreasonable, he might argue — demands to eat more than once a day while on the road.

Of course, the explosion of McDonald’s restaurants and drive-through windows along the highways only solved the problem of quickly feeding the family. Inevitably, with six people in our car, at least one of us would also have to use the restroom. To complete both tasks with maximum efficiency, my father devised a plan that my family, after regular and rigorous practice, eventually executed to perfection. The goal was simple: keep the car’s wheels moving forward at all times. Prior to getting into the drive-through line, my father would take everyone’s food orders and pull up along the side entrance. Then we’d sprint to the restrooms while Dad eased the car ahead to place our order.

At the time, McDonald’s goal was to provide each drive-through customer’s order within 50 seconds. Factoring in a few additional moments for my father to pause — not stop! — while drivers ahead of him ordered, we had about 90 seconds to go to the bathroom and dash out the door to intercept our passing car.

Aside from all else, my family genuinely enjoyed McDonald’s food. It wasn’t fancy, but it was satisfying and predictable. A McMuffin in Milwaukee tasted the same as the one in Memphis; a Big Mac in Burlington was as big as the one in Baton Rouge. Such consistency was an enormous draw for families like mine while out exploring America — it was a familiar taste of home in places that seemed a world away.

Most important, eating at McDonald’s fit our modest travel budget. After all, the restaurant was cheap, and, well, so was my dad — at least when it came to “discretionary” expenditures such as food. Yet even as inexpensive as McDonald’s was, Dad found ways to trim the tab further. If three of us wanted our own regular-size Coke, he’d instead order one large Coke costing half the price and ask for three complimentary kiddie cups. Indeed, long before McDonald’s introduced the super-size concept, my father came up with “shrink-a-size.” If Dad believed one of us had placed an order that exceeded our appetite, he’d simply scale it back. Hence, many an optimistically ordered Big Mac became a less-than-enthusiastically received regular hamburger. We discovered these arbitrary changes too late. It was only after we were at cruising speed and far past any turnarounds that he’d begin distributing the disappointment.

When it came to deciding what and how much food we’d get in a trip to the drive-through, my dad was — in the most literal sense of the phrase — always in the driver’s seat. It wouldn’t be until I had my own driver’s license that I received exactly what I ordered at a McDonald’s drive-through.

Richard Ratay graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a journalism degree and has worked as an award-winning advertising copywriter for 25 years.

Featured image: PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.

This article is featured in the July/August 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.