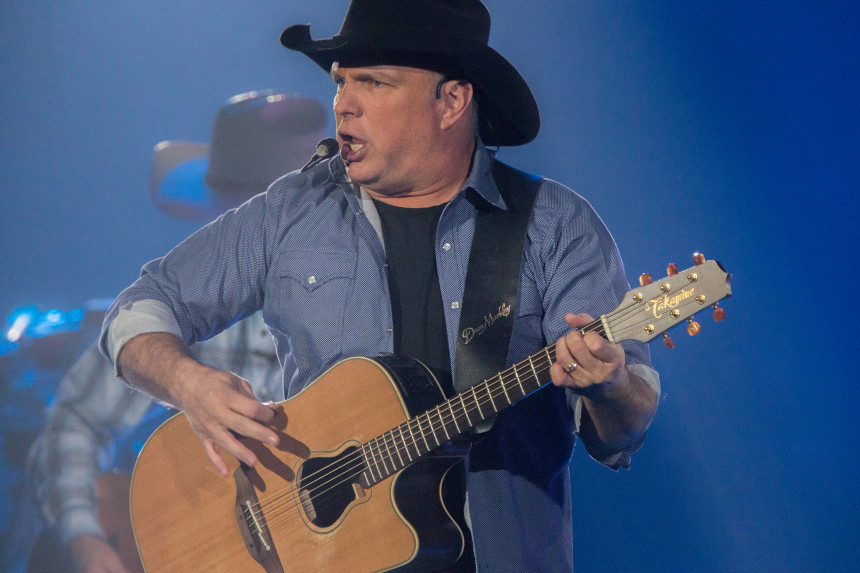

30 Years Ago, No Fences Established Garth Brooks as Country Royalty

It’s hard to decide exactly where to start with Garth Brooks. That he’s the best-selling solo albums artist in the history of the United States? That only The Beatles have sold more albums? What about the fact that he’s the only artist to sell 10 million copies each of nine different albums? Then there’s the pick-up truck full of Grammys, American Music Awards, and gold and platinum records, and that’s before you get to the swelling list of Hall of Fame inductions. He is, after all, the youngest person to receive the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. And even though his debut album was a hit, Brooks truly ascended to next-level stardom with his second effort, No Fences, which hit stores 30 years ago this week.

If you knew Troyal Garth Brooks in high school, you might be forgiven for thinking of him as an athlete rather than a music guy. Born in 1962 in Oklahoma, Brooks would stand out in track and field, baseball, and football. He even went to Oklahoma State University on a track scholarship, specializing in javelin. But the other side of Brooks was that his mother was Colleen McElroy Carroll, a country singer who had been signed to Capitol Records and performed on television shows like Ozark Jubilee. His family held weekly talent shows that all the kids had to take part in; consequently, Brooks learned to play banjo and guitar. At OSU, his roommate, Ty England, played guitar and would soon become Brooks’s sideman.

Brooks graduated OSU in 1984 with an advertising degree, and the following year he began to play the local circuit. His influences came from a wide spectrum, including rock acts like KISS and singer-songwriters like James Taylor. But George Strait and Chris LeDoux in particular were the artists that drove Brooks toward country. Once he got connected in Nashville via entertainment lawyer Ron Phelps, Brooks was on his way toward his first deal.

Brooks put out his self-titled debut, Garth Brooks, in 1989 on his mom’s old label, Capitol. In his first taste of crossover success, Brooks saw his #2 country album also hit #13 on the Top 200.He wrote or co-wrote the first three singles from the record, all of which went Top 10 country, with “If Tomorrow Never Comes” hitting #1. The fourth single was written by Tony Arata; it was called “The Dance.” The #1 hit made Brooks a star on country television with its emotional video that paid tribute to late public figures from the towering (Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy) to the lesser-known (bull rider Lane Frost, singer Chris Whitley). Brooks still considers the worldwide hit to be his favorite song from his own catalog.

However, Brooks’s second effort just a year later would turn out to be landmark not just for him, but for country as a whole. No Fences dominated the Country Albums chart with 23 straight weeks at #1 while also hitting #3 on the Billboard 200. It remains his best-selling individual album, with 17 million copies shipped in the U.S. alone. The album produced four #1 singles (“Friends in Low Places,” “Unanswered Prayers,” “Two of a Kind, Workin’ on a Full House,” “The Thunder Rolls”) and a #7 (“Wild Horses”). In particular, “Friends in Low Places” became a phenom unto itself; after a four-week run at #1, it ended up winning both the Country Music Association and Academy of Country Music Awards for Single of the Year. So pervasive was the song that year that it was a Top 40 hit on the U.K. charts while making the Top 100 on the Eurochart. It now routinely appears on lists of “Best Drinking Songs.”

In stark contrast to “Friends,” “The Thunder Rolls” sparked enormous controversy when Brooks delivered the music video. Composed by Brooks and Pat Alger, the original version of the song had four verses; the song is about a cheating husband, and the last verse suggests that the scorned wife shoots him. Ultimately, the fourth verse was omitted when the song was recorded for the album. However, Brooks felt that he had the opportunity to make a statement, and the moody music video was constructed to make a point about domestic violence. Brooks even portrayed the cheating, abusive husband himself. Almost immediately upon release, TNN (The Nashville Network) and CMT (Country Music Television) banned the video, citing violence and a reluctance to dive into social issues as reasons. VH-1 took up the video a few days later, and Capitol was deluged with requests for the video from alternate venues. The clip was eventually named the CMA Video of the Year and was nominated for a Grammy.

Brooks didn’t let the iron cool before striking again. Ropin’ the Wind shipped four million copies in advance of its September 1991 release. The artist would also soon benefit from the introduction of SoundScan, a new sales tracking system that digitally counted sales by individual unit rather estimates given by store managers and owners. The new system turned album sales on their collective head, demonstrating that genres like country, hip-hop, and alternative rock were actually selling in much larger numbers than had been figured before. The album debuted at #1, was briefly dislodged for two weeks by the release of Use Your Illusion II by Guns N’ Roses, and then retook the top spot for a seven-week run. At the beginning of 1992, Brooks swapped the top spot with Nirvana’s Nevermind before settling in for another eight-week run.

From there, Brooks has had a career that can mostly be summed up by superlatives. His total output since 1989 is substantial on any scale; he’s released 77 singles, 12 studio albums, three Christmas albums, and a number of compilations and boxed sets. While Brooks took his foot off the throttle in the 2000s, actually going 13 years between the releases of Scarecrow and Man Against Machine, and though his most recent studio albums haven’t sold as well, his catalog continues to move and he remains a massive live draw around the world. To date, he’s sold a mind-boggling 170 million records. Brooks has expressed dissatisfaction with the payouts delivered by digital services like iTunes, Spotify, and YouTube, which is why you won’t find his videos on the latter; that situation may have also affected his more recent sales totals in a negative way, given the popularity of digital formats and the fact that those formats now figure into chart data.

Of course, it would be unthinkable to count a personality like Brooks out. Against conventional wisdom, he took a brand of country merged with arena rock to the top of the charts, and kept it there for years. His work remains some of the best known in the genre, and still benefits from significant airplay and back-catalog sales. He’s a member of the Grand Ole Opry, the Country Music Hall of Fame, the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum. Brooks may have staked out country immortality by singing about friends in low places, but he’s put together a career defined by highs.

Featured image: Sterling Munksgard / Shutterstock

Wit’s End: They’ve Turned the Soundtrack of My Youth into Muzak

Read more from Maya Sinha’s column, Wit’s End.

I was in a department store, shopping for items the Victorians called “unmentionables,” when a 1992 song from the British band The Cure began to play.

From hidden speakers, under the bright retail lights, lead vocalist Robert Smith — a pale Goth in eyeliner, lipstick, and a tangle of ink-black hair — sang the opening bars of “Friday I’m in Love.”

This song was deeply familiar from my high school and college years. Back then, Smith was a romantic figure: a moody, sensitive rebel who fronted an alt-rock band. Though he strove to look three-quarters dead, he would not be caught dead in the women’s underwear section of the flagship store in a suburban mall.

Yet here he was in 2020. A wave of cognitive dissonance crashed over me. Why was the store piping in The Cure, a poignant reminder of my vanished youth? Was nothing sacred?

For Americans born between 1965 and 1980, the generation known as Gen X, this is now a common experience while shopping. We select lettuce from a superstore crisper to the rapturous vocals of Belinda Carlisle in “Heaven Is a Place on Earth” (1987). We try on sensible shoes to the late Dolores O’Riordan of the Cranberries singing “Linger” (1993). Checking our tween into the orthodontist’s office, we’re assailed with INXS’s darkly urgent “Devil Inside” (1987) or REO Speedwagon’s earnest “Keep On Loving You” (1980). We gas up our SUVs to the sound of giddy infatuation in Sting’s “Every Little Thing She Does is Magic” (1981).

Decades later, these 1980s and 1990s pop songs still pack a wallop. In a recent essay, Gen X writer Meghan Daum wrote that she’s stopped listening to four decades of pop music, songs that evoke so many bittersweet memories that she now avoids them “as if avoiding pain.”

These one-time radio hits are powerfully evocative, Daum writes, because music “embeds itself into our emotions, often burrowing far deeper than the memories of the events that spurred those emotions. From there, the songs we love become the half-life of our emotions. They are whatever’s left of whatever was going on at the time.”

For people in their 40s and 50s, pop songs conjure memories of childhood, junior high, high school, summers, friends, significant others, college, jobs, holidays, weddings, divorces, and family events. Just little things like that. No biggie.

But if you’re trying to avoid the pain (or mixed feelings) these songs evoke, too bad: The hits of 1980-1999 are playing on continuous loop at the grocery store, a cavernous building you disconsolately roam four times a week. Good luck buying organic peanut butter without crying, Mom! Have fun picking out dog food while tears of regret and forever-lost chances burn your eyes!

The cruel irony of listening to bouncy pop songs from junior year while tossing headache medicine and nutritional supplements called Change-O-Life into the shopping cart is apparently lost on the corporate overlords who devised this torture. Why have they done this, desecrating our memories by canning our music?

Piping music into public spaces was the brainchild of U.S. Army Major General George O. Squier, a renowned inventor who devised a means of playing phonograph records over electric power lines. In 1934, after radio took off, Squier founded the Muzak Corporation, which piped commercial-free music into hotels and restaurants. “The music itself was newly recorded versions of popular songs, but now produced with purposefully mellow, orchestral arrangements,” historian Peter Blecha wrote in 2012.

Research in the 1940s showed that music could influence behavior, and during World War II, Muzak was used to motivate factory and military workers. In the postwar years, the goal shifted to keeping customers in stores, with “soothing, saccharine sounds being pumped into dentists’ offices, grocery stores, airports, and shopping malls all across the nation and overseas,” Blecha explains.

On their journey to the moon in 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts calmed themselves by listening to Muzak. Back on Earth, however, soporific versions of hit songs became known as “elevator music.” In 2011, Mood Media announced that it had acquired Muzak for $345 million, adding to its portfolio of commercial music services for retailers, hotels, restaurants, gyms, and banks. Now supplying music for 470,000 commercial locations around the globe, the company was “delivering unique experiences to millions of people daily.”

Suddenly, elevator music was out; nostalgic pop playlists were in.

In 2020, music still affects shoppers’ moods, but not necessarily in a good way. We Gen Xers feel vaguely insulted when the soundtracks of our youth are cynically used to sell us things. We are this close to buying everything we need online, having it delivered by drones, and listening to our 1980s playlists when we want to, how we want to, in our own homes!

Retailers should take a page from video game designers, who similarly want to keep players engaged for as long as possible. The Legend of Zelda games have gorgeous, critically acclaimed soundtracks, setting the bar for ambient music that’s enjoyable for people of all ages. Why can’t we have original mood music in stores? (Attention, composition majors! A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.)

Until that day, I’ll have to listen to The Cure while going about my mundane errands, draining the music of all meaning. It makes me want to protest in some small but visible way, perhaps by wearing head-to-toe black, dying my hair with shoe polish, and piercing my earlobe with a nail.

By the time I get out of a store that’s recycled my memories to sell toothpaste and dish soap, I’m feeling a little Goth myself.

Featured image: Robert Smith of The Cure, 1985 (AF archive / Alamy Stock Photo)

Pokémon Is Never Going Away

From the time those cute, colorful monsters first entered our lives, it seemed that Pokémon was a problem.

Most of my second-grade class was obsessed with collecting the cards and playing the Game Boy games. Everyone had a favorite Pokémon, and choosing Pikachu was a cop-out and meant you weren’t a dedicated Pokémon trainer. My favorite was Vaporeon, a majestic cat-dolphin creature. We were in our own little world, one in which surreal animals were waiting in tall grasses to be caught and trained for battle.

In the real world, teachers took notice of this considerable distraction, and all Pokémon paraphernalia was banned from the school. Parents were concerned — or just annoyed — with how great a presence these creatures had in our lives. The franchise even posed physical threats to children. In 1997, the television show went on a four-month hiatus in Japan after reportedly causing hundreds of children to experience seizures during a climactic scene in which red and blue lights flashed quickly onscreen. In 1999, Burger King reluctantly recalled its Pokéball toys after a young girl suffocated in California from covering her nose and mouth with one.

Each crisis brought about parental hysteria, but Pokémania persisted. In a 1999 TIME article, Howard Chua-Eoan and Tim Larimer bemoaned the phenomenon and its lessons of ravenous accumulation: “Is Pokemon payback for our get-rich-quick era — with our offspring led away like lemmings by Pied Poke-Pipers of greed? Or is there something inherent in childhood that Pokemania simply reflects?” No one could be sure why this Japanese game took the youth by storm, but plenty of cultural commenters were certain about its lack of staying power. It was “the most effortless Japanese invasion of western pop culture since Mighty Morphin Power Rangers,” Peter Bradshaw wrote in The Guardian. It was a fad, they said.

They were wrong.

One of the misconceptions about the explosive wave of pocket monsters was that the whole sensation was generated into existence by executives looking to sell plush toys. While the merchandising didn’t hurt Pokémon’s potential, it was actually created as a passion project by a bug collector outside Tokyo. Satoshi Tajiri grew up catching beetles with his friends in the quickly urbanizing Machido, Japan. He saw the development of Nintendo’s Game Boy and dreamed up a world inside the console where players could catch and trade creatures using the new connecting device: the link cable. He worked on the concept for six years, inventing an expansive map of towns, caves, and seas a player could navigate to find and capture a miscellany of 150 monsters to train and battle.

More than two decades later, there are 812 Pokémon. The latest movie in the franchise, Pokémon Detective Pikachu, had a $58 million opening weekend in the U.S., the biggest ever for any movie based on a video game. Of course, the odd scandal that seems to follow Pokémon has kept up as well. In Montreal, a theater accidentally played the disturbing horror film The Curse of La Llorona instead of the new Pikachu movie to a crowd of crying children.

Pokémon’s astoundingly resilient popularity is clear, if somewhat surprising to those who have never experienced the accomplishment of catching the elusive and powerful Mewtwo. Part of the reason it has such staying power is the fully realized, imaginative world that the characters and their creatures inhabit. In the games, players are able to role play in that world and spend hours on a personalized adventure that combines competition with collaboration.

As children, we would often express the wish that Pokémon were real, and that we could play the game in the real world. Then, in 2016, The Pokémon Company partnered with Google startup Niantic to release Pokémon Go, an augmented reality game in which players catch Pokémon on their smartphones by walking around parks, monuments, and especially Starbucks. The creatures appear against the backdrop of a live video taken by the phone to give the illusion that a Rattata or an Oddish is actually standing before the player.

The summer of 2016 saw children and adults alike playing the game in droves. College campuses, urban walkways, malls, and hospitals were all transformed into Pokéworlds as trainers sauntered about trying to “catch ’em all.” Just as Pokémon had, years before, been deemed a fad, the free app gained the same reputation as it swept the world that summer. Although the number of Pokémon Go players tapered off later that year, the game was still in the top five gaming apps by number of users last October. Last month, Pokémon Go reached one billion downloads.

Two of those downloads were mine. I got the game as a lark during the summer of 2016, then redownloaded it last year when I was ready to get serious. Not quite play-while-driving serious, but serious enough to take over some gyms and catch a Vaporeon.

Everyone has heard about the dangers associated with the game: robberies, car accidents, gaming addiction. But after it was released, Pokémon Go also generated a substantial amount of attention from the academic world. Study after study dissected the phenomenon for its usefulness in education, child psychology, sociology, and even philosophy. While some saw the game only for its dystopian implications on public life, researchers realized how it could benefit conservation efforts, STEM and literacy education, and exercise rates in young people.

In a paper from Russian Education & Society, the authors praise the possibilities of augmented reality gaming: “This game has strengthened the effects of social interaction, giving them a larger scale, dynamism, and influence. According to UNESCO, these trends have colossal educational potential.” Pokémon Go has led the way in its ability to merge the physical, social, and virtual aspects of gaming. A study in the American Journal of Public Health showed that “playing Pokémon Go increased moderate to vigorous physical activity by about 50 minutes per week and reduced sedentary behavior by about 30 minutes per day,” and a call for qualitative studies on the subject claims “sustained and regular use of the app stands to improve not only physical activity but also mental health, social capital, and social interactions in these key populations [teens, preteens, and younger men].” It might have been disheartening to watch an inflatable couch-ridden preadolescent logging hours and hours of Pokémon Red Version on a Game Boy in 1999, but the same criticisms are hardly applicable in this new era of active, engaged Pokémon hunting.

In 1999, TIME interviewed Satoshi Tajiri about his creation, asking why Pokémon was so popular. He answered, “When you’re a kid and get your first bike, you want to go somewhere you’ve never been before. That’s like Pokémon. Everybody shares the same experience, but everybody wants to take it someplace else.”

My own experience with Go was as nostalgic as it needed to be and novel enough to be exciting. Though I have to admit my disappointment with the concepts of some of the newer monsters — one is a balloon and another is an actual bag of trash — the magical thoroughness of the Pokémon world holds up. I even took second (and third) looks at the monuments surrounding a nearby park as I would walk my dog, since they were also virtual Pokéstops that harbored the necessary Pokéballs.

Does this mean I’ll be buying tickets to the new movie? Attending the Pokémon Go Fest in Chicago this June? It’s not likely. But plenty of others will, and the “fad” will live on.

Image by Traci Lawson on Flickr, edited.