The Years of Deadly Underground Abortions

“There is no way getting around this: this is a frightening time,” Washington Senator Patty Murray began as she addressed a crowd outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. this week. They were gathered for the “National Day of Action to Stop the Bans,” a nationwide string of protests against recent legislation aimed at restricting abortion access in several states. As protesters waved signs reading “Keep Abortion Legal” or wire clothes hangers with “Never Again” written on them, Murray called the legislation in Alabama, Missouri, Mississippi, and other states “cruel,” “extreme,” and “designed to control women’s decisions and criminalize doctors.”

Last Wednesday, Alabama governor Kay Ivey signed the Alabama Human Life Protection Act into law, noting that the extremely restrictive and controversial ban may be unenforceable, but will likely act as a call on the U.S. Supreme Court to revisit its 1973 decision on Roe v. Wade.

In the years leading up to that landmark decision, a patchwork of state laws made abortion legal in some places and illegal in others, based on life-threatening circumstances, incest, or rape. While, in 1970, a woman in Washington could obtain an elective abortion legally, a Kentucky woman could not. Does this mean abortions weren’t performed in Kentucky? Or Texas? Or Alabama? After all, before 1967, the procedure was basically a crime in every state, yet estimates of abortions in the 1950s and ’60s range from 200,000 to 2 million each year. The women who sought underground abortions during this time period often faced painful, and sometimes deadly, consequences.

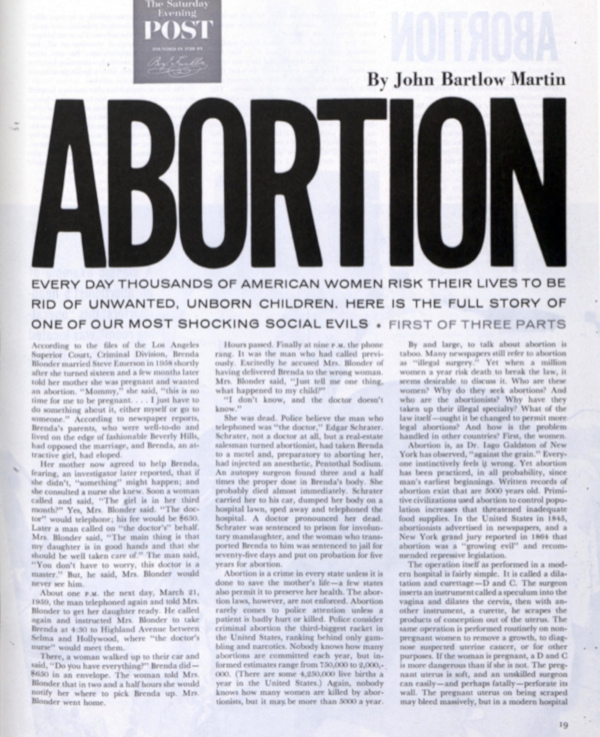

In 1961, the word “abortion” was an unpalatable one to much of the public. Nevertheless, it appeared in bold print on the cover of this magazine, which called it “a widespread social evil.” In the feature story, John Bartlow Martin investigated women who had abortions as well as the “abortionists” who performed them. He found that women who sought out abortions were sometimes poor, desperate, and single, while others were wealthy and married. What connected them was a willingness to break the law in order to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. What separated them was their means to do it safely.

The surgical procedure itself has changed significantly in the decades since Martin’s report. In the ’50s and ’60s, a dilation and curettage was the safest method of abortion in the U.S. During a D&C, the surgeon dilates the cervix and uses a curette to scrape the lining of the uterus. The procedure is tricky, but safe when performed correctly. The risks of a “back alley” D&C include infection, perforation of the uterus, and uncontrolled hemorrhage.

These risks were undertaken by scores of women during this time period who navigated difficult back channels to find an — often very expensive — abortionist. The D&C was not the only method used in underground abortions either. Martin describes a “pack job,” in which the administrator would “dilate the cervix and pack gauze into the pregnant uterus. The uterus will contract in an effort to expel the foreign body; its contractions develop into labor pains, and it expels the fetus.” Still more gut-wrenching was the practice of inserting soap or other chemical solutions into the uterus to induce miscarriage. Apart from the toxicity, there is a risk of air bubbles entering the bloodstream and causing instant death.

One Los Angeles girl that Martin interviewed traveled to Tijuana to find someone to abort her pregnancy:

“We went up those stairs,” Jean recalls. “The office was real nice, very clean. The doctor asked, ‘What can I do for you?’ I told him I wanted to see about a D and C. He said his price was three hundred dollars. Robbie said all we had was one hundred and fifty dollars. The doctor told me to go into the operating room and take my clothes off. He examined me and said I was three months pregnant. Then he started talking to me.” He made suggestive remarks and agreed to do it for $150 “because he liked me.”

Jean recalls, “I was crying and shaking; I was never so scared in my life. Another doctor came in and gave me Sodium Pentothal. When I woke up my girlfriend says I was begging God to forgive me. It hurt so bad I started to scream. The doctor put his hand over my mouth and said, ‘Shut up, you’ll get us all in trouble.’ he gave me some pills and told me I had to get out. He let us out through a back door. I could hardly stand up.”

Her uterus was perforated, and she spent two weeks in the hospital.

Leslie J. Reagan wrote extensively about the pre-Roe v. Wade atmosphere of abortion in her book When Abortion Was a Crime. In regard to the 1950s, she writes, “There was a notable shift in illegal abortion practices in this period. It was not until the postwar period, quite late in the history of illegal abortion, that women’s descriptions of illegal abortions included meeting intermediaries, being blindfolded, and being driven to a secret and unknown place where an unseen and unknown person performed the abortion.”

In the early century and through the Great Depression, hospitals and clinics were performing more and more “therapeutic abortions,” but crackdowns on clinics in the ’40s and ’50s and the addition of stricter hospital boards limited this practice. The number of therapeutic abortions in New York City was reduced by more than half from 1942 to 1962, and the number of women who died from abortions there almost doubled between 1951 and 1962. In Cook County Hospital in Chicago, the annual number of admissions due to abortion-related complications was around 1,000 in 1940. By 1963, the number was more than 4,500.

Although abortions had already been dangerous and largely inaccessible to many, the postwar years saw further limits on access to the procedure in a hospital. This drove more women to self-induced methods or quack doctors and left them vulnerable to excruciating complications, sexual assault, and death.

In 1959, 16-year-old Brenda Blonder was found dead on the lawn of Burbank Hospital in Los Angeles with three and a half times the proper dose of Sodium Pentothal in her body. Her mother had arranged an “illegal surgery” with a former salesman after the girl threatened to try it herself. Since Blonder belonged to a wealthy family, her death — and others like it — illustrated the problem of underground abortions that had plagued poor women and women of color for decades. In 1961, women of color in New York City faced four times as many deaths from abortion as white women, with abortion deaths accounting for almost half of maternal deaths of women of color.

In a recent interview with NPR, historian Karissa Haugeberg spoke about the current availability of abortion in the U.S., saying “we’re returning to this period where geography matters tremendously” for access to abortions. Washington state has 34 abortion facilities, or about one for every 50,000 women of reproductive age. Mississippi has one facility for about 700,000 women, Kentucky has one for its 1 million women, and Missouri has one for almost 1.4 million women. The implications of these disparities on class and race echo the inequality of abortion access that has existed for centuries in the U.S.

In the mid-century, restrictions to abortion — or any of the procedure’s various names — caused a public health crisis. While the number of reported annual deaths due to abortion complications in the 1950s was around 300, John Bartlow Martin, in his story for the Post, suggests that hospitals often underreported and that the number could be as high as 5,000. As shocking a statistic as that would seem, there is no way of knowing how he arrived at it. The most recent number from the CDC on annual abortion-related deaths is from 2014, and it’s much lower: six.

Featured Image: Sid Avery, The Saturday Evening Post, May 27, 1961