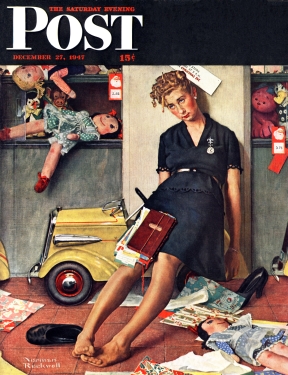

Toy Story

Christmas rush is over. The foot-weary toy department salesgirl has slumped down the wall and into the seat of a toy car — the face of exhaustion. Shoes off and toes seeking relief, she survived another holiday season. Judging by the bulging book in her lap, sales were brisk. Though surrounded by chaos — toys gawking at her from every angle and wrapping paper on the floor — she has momentarily left the building perhaps thinking of her own kids and Christmas nearby.

Santa’s Helper, which graced the issue of the Post on December 27, 1947, is pure Norman Rockwell — visual storytelling at his best. “For me, the story is the first thing and the last thing,” Rockwell once said.

Rockwell began work on this cover during a hot mid-summer in Chicago. Like a movie director, he framed the story around a central idea, chose the models, the settings, the costumes, the props, and directed the pose, even the facial expression. He set the scene in the actual toy department at the big Marshall Field store — then the Grande Dame of American department stores. Marshall Field obligingly supplied him with all manner of toys and props, but as the artist worked he felt he needed more dolls, so went out and bought them himself. A perfectionist, Rockwell was not satisfied with the salesgirl first picked as the model, so for weeks he visited other stores, peering at the help, looking for just the right face. And he found it in the person of Sophie Aumand — a waitress from Springfield, Massachusetts.

And with that final ingredient in place, Rockwell was ready to render the final painting, in the process creating an enduring image of Christmas every American — even today’s frenzied online shoppers — will understand.