Review: Capone — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Capone

⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Run Time: 1 hour 43 minutes

Rating: R

Stars: Tom Hardy, Linda Cardellini, Matt Dillon, Kyle MacLachlan

Writer/Director: Josh Trank

Streaming on Amazon Prime, iTunes, and other video-on-demand platforms

One thing’s for sure with this grumbly, sweat-soaked account of mob boss Al Capone’s last days: Nobody is slumming it.

In the title role, Tom Hardy (Dunkirk) plunges headfirst into the crumbling mind and body of a one-time tough guy, now riddled by syphilis-steeped dementia. Writer/Director Josh Trank (Chronicle, The Fantastic Four) breaks all the rules of gangster filmmaking, trading lethal swagger and explosive shoot-outs for spiraling decrepitude and fever-induced hallucination. And cinematographer Peter Deming, a longtime David Lynch collaborator, leads the viewer into a dark, disorienting half-real, half-illusionary house of mirrors. Even hip-hop legend El-P’s musical score, a barely-there tone poem of jarring dissonance, provides layers of troubling sonic atmosphere.

But despite all these artists clicking on all cylinders — or maybe, in a perverse way, because of that — Capone never really engages its audience, keeping us at arm’s length even as it probes the most private recesses of a character’s psyche.

We meet Al “Scarface” Capone — or Fonse, as he prefers to be called these days — on Thanksgiving, 1945, six years after he was released from federal prison and sent home to die of the venereal disease that was eating his brain. History tells us Capone was among the first people in the country to receive penicillin treatment for syphilis, in 1942, but it was too late to save his ravaged body and mind. (At a loss for anything to help his doomed patient, Fonse’s doctor, played with upbeat enthusiasm by Kyle MacLachlan, prescribes raw carrots to replace Capone’s ever-present cigars.)

Capone traces the year between the last two Thanksgivings of Capone’s life. Stooped and at times barely coherent, his trademark facial scars drooping like a falling curtain, Capone shuffles around the Miami mansion he bought with his kingpin fortune. He barks demands for food, drinks, and cigars from his long-suffering yet somehow loyal wife — played with tough tenderness by an under-used Linda Cardellini (Mad Men) — and listens in childlike awe to radio dramas re-creating the most sordid chapters of his life, like the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

As Capone’s mind disintegrates, he finds solace in the company of ex-gang members, who may or may not be real, but who satisfy his yearning to still be the Boss. His memories also haunt him as he re-lives tortured scenes from his past, including the frenzied, fuzzy recollection of having fathered a son by a woman who died in a mob shootout.

For Fonse, grim reality and fever dream fantasy interweave like the lines of a somber jazz piece echoing in a seedy Chicago speakeasy. Suffering perpetual sweats, debilitating coughing fits and persistent (not to mention distressingly graphic) incontinence, Fonse becomes progressively agitated to the point where he pulls out an old gold-plated Tommy gun and starts spraying bullets all over the place.

Or does he? Indeed, Capone plays the is-it-real-or-is-it-memory card so often the film threatens, by the end, to become an impenetrable slog. There’s no denying the movie’s cerebral ambitions — but its heart lies somewhere at the bottom of Lake Michigan, wearing a pair of cement shoes.

Featured image: Tom Hardy as Al Capone in Capone (Photo Credit: Courtesy of Vertical Entertainment)

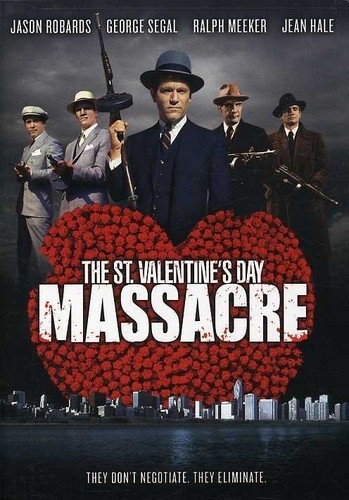

5 Things You Didn’t Know About the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre

February 14th. It’s a day for cards, flowers, and gangland slayings; at least it was on 1929, when five members of Chicago’s North Side Gang and two affiliates were gunned down in a garage in the Lincoln Park neighborhood. The man at the center of it all, as he was in many things in Chicago at that time, was Al Capone, even though the actual triggermen have never been identified to a certainty. Though the act lives on in various films and as a reference in popular culture, the actual whos and whys have largely been forgotten by the public. Here then are five things you may not know about the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

1. What Happened at the Scene?

This much is certain. It was 10:30 am, a Thursday, at the garage on 2122 North Clark Street. Witnesses saw two men dressed as police officers and two other men wearing suits, hats, and overcoats, leaving immediately after the shooting; the “police” held their guns on the other two and marched them away. Minutes later, the actual police arrived. Six men were dead and one, Frank Gusenberg, was mortally wounded, having taken 14 bullets. Yes, 14. Remarkably, he was still conscious but refused to cooperate, even going so far as to say, “No one shot me.” Frank Gusenberg died just a few hours later.

The rest of the victims included: Gusenberg’s brother, Peter; Albert Kachellek, who also went by the name James Clark; Albert Weinshank; Adam Heyer; Reinhardt Schwimmer; and John May. May’s dog, Highball, was also present, but unharmed. Other witnesses outside had seen the “police” and the other two men arrive; the “police” carried Thompson submachine guns and the other two men had shotguns. From what the police discovered inside, the group of four lined the victims up against the wall of the garage and fired repeatedly, even after the men were down.

2. Who Were the Victims?

All seven men worked either directly or indirectly for George “Bugs” Moran. Moran led the North Side Gang, an Irish-American criminal organization, and a major rival to the operations of gangster Al Capone. Kachellek/Clark was Moran’s brother-in-law and right-hand man. Brothers Peter and Frank Gusenberg worked as “muscle” or “enforcers” for Moran. Heyer served as the gang’s business manager and bookkeeper. Weinshank managed businesses that were used as fronts for Moran’s operations. Schwimmer was an associate of the gangsters, a former optician and inveterate gambler. May, an auto mechanic, sometimes did work for Moran’s people.

Over time, it was discovered that men were lured to the warehouse with the promise of obtaining a shipment of Canadian whiskey that had been stolen from Capone. Capone’s associates laid the trap, expecting Moran himself to arrive. However, Weinshank bore a strong resemblance to Moran, and it’s believed that the gunmen went ahead and acted, thinking that they actually had Moran already.

3. What Was the Motive?

Capone’s outfit had clashed with the North Side Gang for years. Since 1924, a number of previous leaders of the North Siders had been killed by men working for Capone or his predecessor in the Chicago Outfit, Johnny Torrio. Their enmity arose from issues stemming from territories, control of various criminal practices in the city, and the general ethnic conflict born from the North Siders being predominantly Irish and the Outfit’s deep Italian background. The immediate flashpoint for the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre came from the battle over running liquor in Prohibition-era Chicago, which included Moran men hijacking Capone shipments, as well as Moran’s encroachment on Capone’s dog track and saloon revenues.

4. What Was the Fallout?

The Massacre all but broke the back of the North Side Gang. While it would continue to exist, its power and influence was greatly diminished. Capone’s reach only grew, but the Massacre prompted an outcry from the citizens and greater concern from all levels of law enforcement. While many people were implicated in the crime, no one was ever convicted, and most of the people possibly connected with the actions would be murdered themselves.

The United States government began to get involved, with an IRS investigation into Capone and the eventual dispatch of Bureau of Prohibition agent Eliot Ness to the city. Ness formed his famous “Untouchables,” a group of agents known for their refusal to take bribes. The combined efforts of Ness and the other investigations would cost Capone millions and eventually see him convicted on five counts of tax evasion in 1931. Capone served seven years in prison; he was paroled in 1939, but suffered the rest of his life from neurosyphilis and paresis (paralytic dementia) before dying of a stroke in 1947.

5. Why Is It Remembered?

It’s hard to say why the Massacre casts such a long shadow. Certainly, the association with the holiday is something that cemented it in the minds of the public. The connection with Al Capone, famous in his own right, increases its mystique. And it’s certainly a key event in the much-mythologized Prohibition Era of Chicago. Much like the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, the Massacre has been the subject of many book and film adaptations, either in direct adaptations like the 1959 film Al Capone, the 1967 film The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, or as an off-screen, background event as in 1987’s The Untouchables with Kevin Costner as Ness and Robert DeNiro as Capone. The Massacre has also become an unlikely staple of comedic references, perhaps most famously in the 1959 comedy Some Like It Hot, which implies that Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis go on the run because they witnessed the Massacre.

Feature Image: Chicago in 1924, with the New Union Station in foreground. (Chicago Architectural Photographing Company; Wikimedia Commons via Public Domain)

The IRS Has a Secret Admirer

Ever since I was a kid and read that Al Capone was arrested for tax evasion, I have feared the Internal Revenue Service. Think of it, Al Capone had killed a zillion people, and while the police were trying to find proof to arrest him for murder, a skinny nerd with a green eyeshade nailed Capone for tax evasion. Insofar as it is possible, I try never to irritate the IRS.

In an effort to stay on the good side of the IRS, I’ve offered them several suggestions to keep them in the black. For starters, since I’m self-employed, I have to pay my income taxes four times a year. I always forget to pay until the day they’re due and end up paying with a credit card so I don’t get arrested and sent to Alcatraz like Al Capone. I use a Kroger credit card, but if the IRS had a credit card, I would use theirs. Credit card companies make $20 billion a year, give or take a few, and it’s time the IRS got a piece of the action. Using an IRS credit card could earn points toward a tax deduction. If you ratted out your tax delinquent neighbor with the barking dog that poops in your yard, you could get bonus points. It was a great idea, but the IRS hasn’t responded.

Or, consider a lottery play: Powerball recently hit $587.5 million. Two families split the money. Chances are good they’ll do something stupid with it and ruin their lives. Since the lottery and the IRS are both run by the government, it makes sense for the lottery to rig it so the IRS wins. For a $2 investment, the IRS could have made $587.5 million. Before long, the government would be awash in money, free of debt. I sent this suggestion to the IRS, but nothing came of it.

They also didn’t respond to my suggestion they buy metal detectors and hit the beaches on the weekend. There have been thousands of shipwrecks over the years, most of them involving ships filled to the brim with gold doubloons. Nic Davies of Shrewsbury, England, in his first venture out with a metal detector, found 10,000 ancient Roman coins buried in a clay pot. Officials estimate they’re worth a billion zillion dollars. Personally, I don’t care for treasure hunters because they dig holes, don’t bother to refill them, and I fall in them and break my legs. But if the IRS agents found enough buried money so we wouldn’t have to pay taxes anymore, I’d learn to cope.

In that same vein, the IRS could send its employees out to garage sales to buy Van Gogh paintings hidden underneath dogs-playing-poker pictures. A half dozen times a year I hear of someone doing this. It’s a great way to make some fast money, but when I wrote the IRS, there was no reply. Nothing. Nada. Zip. It’s no wonder our country’s coffers are empty.

To hear people talk, you’d think the IRS was invented by Adolf Hitler. In fact, it was created in 1862 by Abraham Lincoln to help pay for the Civil War. In nearly every presidential poll, Lincoln ranks as our favorite president. The Republicans refer to themselves as the Party of Lincoln, because, if they called themselves the Party of the IRS, they’d never win another office. Don’t get me wrong, I love and admire the IRS and wish them nothing but the best.

We are fast approaching another April 15, my favorite day of the year. Most people hate that day, but not me. (Did I mention my admiration for the IRS?) I’ll spend the weeks leading up to it carefully going over my financial records, making sure to report every dollar I’ve made in the past year, even the $50 my mom and dad gave me for Christmas. If you happen to work for the IRS, I know you’re busy checking everyone’s return. Save yourself the time and trouble, and don’t give mine a second glance.