The World’s First Bad Acid Trip

The world’s first bad acid trip happened 75 years ago in northern Switzerland.

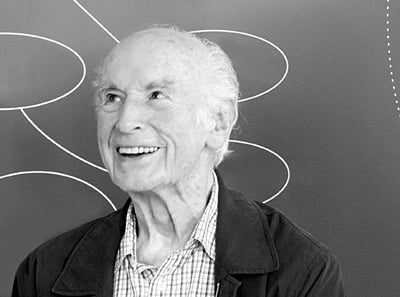

In 1938, chemist Albert Hofmann was working with alkaloids of ergot, a rye fungus responsible for several epidemic-like poisoning events throughout European history, when he synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25). Hofmann was trying to create new obstetrics medicines, and his LSD-25 seemed to have little scientific use. Nevertheless, on a whim, Hofmann synthesized it again five years later. How the substance was first absorbed into his bloodstream remains a mystery, but it set off a psychedelic revolution that would eventually transform pop culture and technological innovation forever.

Upon returning home from his lab on April 16, 1943, Hofmann lay on his couch and closed his eyes to experience an “uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors,” according to his 1979 memoir LSD: My Problem Child. The curious intoxication so intrigued Hofmann that he planned a series of secret, intentional experiments with the drug.

The first of these experiments took place three days later. Hofmann was riding a bicycle home from his laboratory —accompanied by his assistant — when he began to feel the hallucinatory effects. They had cycled because of wartime restrictions on automobiles, and Hofmann’s trippy ride is still commemorated by psychedelic enthusiasts who celebrate “Bicycle Day” on April 19th (a concert this year in San Francisco will feature an electronic band called Shpongle). Returning home, Hofmann requested milk from his neighbor who, in his state, appeared to him “a malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.” The comforting familiarity of his living room had given way to a nightmarish scene of threatening forms, and, as Hofmann noted, “Even worse than these demonic transformations of the outer world, were the alterations that I perceived in myself, in my inner being.”

Hofmann believed he was going insane or, perhaps, dying. His assistant called on the family doctor, who arrived after the worst of his freak-out had subsided (and after Hofmann had drunk more than two liters of milk). His doctor pronounced him to be perfectly fine. Hofmann slowly regained his sense of reality and, the next day, reported a renewed clarity and enjoyment of life. His most earnest insight from tripping was learning that “what one commonly takes as ‘the reality,’ including the reality of one’s own individual person, by no means signifies something fixed, but rather something that is ambiguous — that there is not only one, but that there are many realities, each comprising also a different consciousness of the ego.” He was fascinated with the drug’s ability to change its user’s state of consciousness without disrupting the ability to record and retain information. Hofmann had an out-of-body experience, and he remembered it all.

The most astonishing characteristic of LSD, according to Hofmann and his colleagues at the time, was that it could deliver such profound psychological effects at such a low dose (fractions of a milligram). Hofmann’s results were “replicated” in the scientific community, and 20 years later Timothy Leary was passing the stuff out like candy at Harvard.

Hofmann was wary, however, of the widespread, uncontrolled use of powerful psychedelics. When he met Leary, in 1971, he expressed regret that the publicity of the former Harvard professor’s LSD proselytism among American youth had ruined the possibility of psychedelics’ having a role in academia in the states. Hofmann held hope that acid could aid in psychiatry, and indeed save the world, up until the end of his 102 years. But he never deluded himself with regard to his creation’s darker potential. After all, he had experienced it firsthand.

A result of psychedelia that perhaps no one could have predicted was the tech boom. At least, that’s a connection that John Markoff makes in his book What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. According to Markoff, most of the Bay Area engineers and programmers behind computer development and research in the ’60s were no strangers to LSD. Douglas Engelbart, who first conceptualized the mouse, took part in acid tests with the International Foundation for Advanced Study along with early pioneers of virtual reality and Cisco developers. Even Steve Jobs, the famous Apple founder, regarded tripping as one of the most important experiences of his life.

The year before he died, Hofmann wrote a letter to Jobs imploring the tech giant to “support Swiss psychiatrist Dr. Peter Gasser’s proposed study of LSD-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with anxiety associated with life-threatening illness.” Hofmann had read about Jobs’ formative LSD encounters. “I hope you will help in the transformation of my problem child into a wonder child,” he wrote. Though Jobs responded to the inquiry, he never donated to the cause.

Though LSD may only seem to be a cultural symbol frozen in time for many, the aforementioned Dr. Peter Gasser’s study has commenced. It has found that LSD therapy helped reduce anxiety by about 20 percent in a group of terminally-ill patients. A new era could yet be in store for the peculiar wonder drug, while, for some, it never went away. From the original Bicycle Day to Burning Man, acid has established itself firmly in the culture — and consciousness — of the Western world in its 75 years of existence, for better or worse.