Three Frequently Imitated Films of 1954

Almost since the beginning of movies, people have been remaking movies. There have been more than 538 films based on Dracula alone. Just beyond the remake is the notion of “this film, but this way;” that’s how the pitch of “Die Hard on a bus” becomes Speed. In 1954, however, something was in the air with a trio of classic films that saw their plots reused, recycled, and rebooted in any manner of ways. From a Japanese classic to Lucy and Desi, here’s a look at some constantly copied classics.

Seven Samurai

Director Akira Kurosawa was no stranger to people repurposing his plots; his multiple perspective classic from 1950, Rashomon, has had its plot borrowed by everyone from Quentin Tarantino to the creators of Dawson’s Creek (Season 3’s “The Longest Day”), and The Hidden Fortress was a major influence on Star Wars. Apart from being one of the greatest action movies ever made, Seven Samurai codified the notion of the “men on a mission” film, wherein trouble is instigated, an expert is recruited, said expert assembles a team, and said team battles the threat.

The restoration trailer for Seven Samurai (Uploaded to YouTube by Rotten Tomatoes Trailers)

Kurosawa wrote the screenplay with Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni. Their first crack at the plot yielded a story that they were calling “Six Samurai,” but after some reconsideration, they thought that they needed one character who was a bit more of a wild card. That became Toshiro Mifune’s Kikuchiyo. With a more humorous character in place, the other personalities settled around him, creating some of the archetypes that became familiar in later action films (the wise leader, the leader’s steady right-hand man, the crazy guy, the quiet but effective fighter, etc.). You can see that reflected in everything from The Dirty Dozen to The Fast and the Furious franchise (notably Fast Five). In American comics, lineups for both DC’s Justice League and Marvel’s Avengers frequently contain seven members, which is often seen as a nod to the team balance and composition that Kurosawa and his collaborators used.

The group’s leader, Kambei (Takashi Shimura), gets an introductory subplot that critics like Roger Ebert also noted as incredibly influential. When the audience first meets Kambei, he’s in the midst of other things, eventually rescuing a child. Ebert theorized that this set the trope of introducing a character by showing them on a mission or job that isn’t related to the main plot, but allows them to demonstrate skills that they later use in the main story. One modern example would be Black Widow’s introduction in Avengers; while you’d know her capabilities if you saw Iron Man 2, Avengers brings her into the story in the middle of spycraft that she resolves by apprehending the Russian arms dealers before departing to answer Agent Coulson’s call. The James Bond films are also famous for this technique, frequently opening with what some critics referred to as a “prelim slammer,” an opening action scene to get the audience right into the movie before the main plot unfolds.

The particulars of marauding bandits plaguing a peaceful village have been directly adapted an endless number of times. Some of the most famous versions would include: John Sturges’s Western classic The Magnificent Seven; Pixar’s A Bug’s Life; and the fourth episode of the first season of The Mandalorian, “Sanctuary.” Obviously, The Magnificent Seven became its own mini-franchise of sequels, remakes, and TV series versions, but it all goes back to Kurosawa.

One particularly fun example of a Seven Samurai homage is 1980’s Battle Beyond the Stars, a science fiction spin on the story that wears its Kurosawa and Star Wars influences on its sleeve. Produced by Roger Corman and directed by Jimmy T. Murakami, the film swaps a village menaced by raiders for a planet menaced by raiders (the planet is even named Akir as a nod to Kurosawa’s first name). Young Shad (Richard Thomas) takes the job of recruiting a variety of humanoid aliens to come help (one of whom, in a double-reference score, is playing by Robert Vaughn of The Magnificent Seven). One of Corman’s model makers was promoted to essentially handle the special effects, production design, and art direction on the film; that was a major break for young James Cameron, who would direct The Terminator four years later.

Rear Window

Director Alfred Hitchcock and screenwriter John Michael Hayes adapted Rear Window from Cornell Woolrich’s short story, “It Had to Be Murder.” Like Kurosawa, Woolrich was a frequent source of inspiration; before his death in 1968, his novels and short stories had been adapted for film 30 times. Much of that adapted success came from the reliable story engines that Woolrich built. In the case of “Murder,” the central idea of an observer seeing just enough to understand that a crime has been committed, but unable to prove it, presents all kinds of interesting directions a creator can go.

Rear Window trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Rotten Tomatoes Classic Trailers)

One of the film’s central set pieces, which has wheelchair-bound Jeff (Jimmy Stewart) watching while Lisa (Grace Kelly) tries to quietly evade Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr) in the opposite apartment, has been imitated in countless pieces afterward. A notable example is in James Cameron’s Aliens, where Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and other characters watch on a screen as the Colonial Marines enter what turns about to be an alien hive; Ripley, understanding the danger, struggles to get Lieutenant Gorman to get the Marines out before disaster strikes. The tension-building, quick cuts, and situation of an observer helplessly watching the danger unfold owes much to Rear Window.

Rear Window not only influenced many other films like Dressed to Kill and Disturbia, but also inspired children’s books like The View from the Cherry Tree and countless television episodes (including, strangely enough, the enormously fun 1976 Halloween episode of Little House on the Prairie, “The Monster of Walnut Grove”).

The Long, Long Trailer

The Long, Long Trailer isn’t unique for being the adaptation of a popular book (this one by Clinton Twiss). And it’s not unique for casting a real-life couple as comedic leads. What set it apart at the time was that the stars of the film were also the stars of the #1 show on television at that moment. Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz had been dominating the ratings since 1951 with the launch of I Love Lucy, and they would continue that show’s run until 1957 (before transitioning to The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour, which ran until 1960). Despite their fame and popularity, MGM had some consternation about whether or not paying audiences would show up for a couple that they could see for free on TV. It turned out . . . they did.

The Long, Long Trailer trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Rotten Tomatoes Classic Trailers)

While the movie might not be as well remembered as the first two, it had an outsized impact in terms of framing a comedy around a disastrous road trip that followed the acquisition of a particular vehicle. Shades of that show up in 1983’s National Lampoon’s Vacation, 2006’s RV, and many more. One could even argue that We’re the Millers fits into this little subgenre. Central to the film is the number of self-inflicted mishaps caused by the characters making bad decisions. The roots of many Clark Griswold foul-ups can be found in scenes like Lucy attempting to make dinner in the trailer while Desi is driving. The movie set a template for movie road trips that’s become an ongoing point of reference

Vault: Alfred Hitchcock’s Catty Cockney Quotes

Originally published December 15, 1962

Probably the most distinctive thing about Hitchcock is that in an industry noted for executives who gingerly avoid criticizing anything or anybody, he spews a constant stream of delightful Cockney-accented vituperation. Following, listed by subject, are some examples of Hitchcockian curmudgeonry which he expressed to me:

Disney, Walt: “I used to envy him when he made only cartoons. If he didn’t like an actor, he could tear him up.”

Television, Commercials On: “Most are deadly. They are perfect for my type of show.”

Fans, intellect Of: “Most of my fans are highly intelligent people per se, or they wouldn’t be watching my shows. Some, however, are idiots. One man wrote to me, after I had Janet Leigh murdered in a bathtub in Psycho, that his wife had been afraid to bathe or shower since seeing the film. He asked me for suggestions as to what he should do. I wrote back, ‘Sir, have you considered sending your wife to the dry cleaner?’”

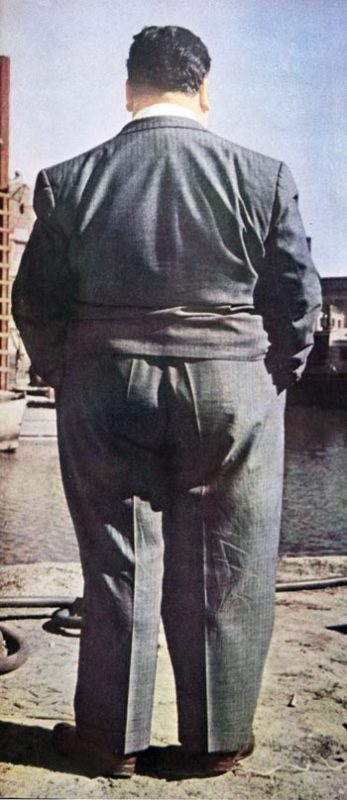

Hitchcock, Alfred, Girth Of: “A few years ago, in Santa Rosa, California, I caught a side view of myself in a store window and screamed with fright. Since then I limit myself to a three-course dinner of appetizer, fish, and meat, with only one bottle of vintage wine with each course.”

Actors, Childlike Qualities Of: “There is no question that all actors are children. Some are good children; some are bad children; many are stupid children. Because of this childlike quality, actors and actresses should never get married. An actress, for example, attains the blissful state of matrimony and almost immediately goes to work in a picture with a new leading man. She plays a love scene with him so passionately that after three weeks on the picture she comes home to her husband and says idiotically, ‘Darling, I want a divorce.’ They are children who never mature emotionally. It’s a tragedy.”

Television, Quality Of: “The television set now is like the toaster in American homes. You press a button and the same thing pops up almost every time.”

Star System, Absurdity of: “The movie star is no longer important. The picture is. If you check, you realize that in recent years the biggest stars, like Audrey Hepburn and Marlon Brando, have disappointing records at the box office. The star is no better than the story. In the right picture the star will be as big as ever; put him in the wrong picture and you’re no better off than if you used an unknown. There is a perfect analogy in public affairs. Right after World War II, who could have conceived that the great Churchill — the biggest star on the world stage — could be thrown out of office and rejected by the very people he had saved from disaster? What happened? The big star was in the wrong picture. The script called for a domestic-problems hero instead of a war-problems hero.”

Novak, Kim: “With a girl like Kim Novak you sometimes delude yourself into thinking you are getting a performance. Actually she is just an adequacy. The only reason I used her in Vertigo was that Vera Miles became pregnant.”

Such barbed utterances, in addition to his impudent gargoyle face seen on TV each week, have become two of Hitchcock’s trademarks in the entertainment world. He has others, as well. There is, for example, the Hitchcock practical joke, and, like everything else he says or does, the joke frequently is a sly answer to something that Alfred Hitchcock resents. Not long ago he became incensed over the Hollywood party at which the seating arrangement was as excruciatingly important as that of a diplomatic affair. So Hitchcock threw his own lawn party, complete with delicacies and red-coated waiters from Chasen’s Restaurant. Forty people showed up, but when it came time to sit down for dinner, all the place cards had phony names on them and no one knew where he was supposed to be. Jimmy Stewart’s wife said to him, “My Lord, we haven’t been invited,” and they left. Everyone else shuffled about in embarrassment until Hitch got up and told them it was a gag. They all then sat down at the nearest place, catch-as-catch-can, and we had a wonderful dinner. But Hitch, as usual, had made his point.

Hitchcock’s own training during the golden age of the silent films was as suspenseful and as harrowing as his own pictures, but, as he says, “I learned. There is no mill like this anymore.” He went on to make such classic British thrillers as The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes, and then, after being summoned to Hollywood in 1938, he continued to add to his reputation as the master of suspense with Rebecca, Spellbound, Notorious, Rear Window, etc. Today, with his movies, his TV show, and his Alfred Hitchcock mystery books and magazines, he nets close to $1 million a year. He has long since become an American citizen, a designation of which he is extremely proud, and which, he says, “gives me the constitutional right to comment acidly on all the ludicrousness around me.”

Not long ago, in the glow of conviviality engendered by a round of magnificent dinners with Hitchcock in his favorite San Francisco and Los Angeles restaurants, I screwed up my courage sufficiently to ask him to comment acidly about himself, as he had about so many others. He thought for a moment and said, “You know, despite all my bluster and bravado, I’m really quite sensitive and cowardly about many things. You’d never believe it, but I’m terrified of policemen and entanglements with the law, even though I make my living from dramatizing such situations. That’s why I haven’t been able to drive a car since I migrated to the United States. Even the thought of getting a traffic ticket throws me into a panic. Another thing I’m afraid of is going to see any of my pictures with an audience present. I only tried that once, with To Catch a Thief, and I was a wreck. I’m scared of seeing the mistakes I might have made.”

Then, as I took the master of the macabre home (I drove — he has his fear of police entanglements), he concluded with a Hitchcock parable: “I guess I’m like the murderer who is taken to the gallows, and he looks at the trap and says, in alarm, ‘Is that thing safe?’”

—“Alfred Hitchcock Resents”

by Bill Davidson, December 15, 1962