The Photographer and the Spy

Ollie Atkins was there when Alger Hiss’ career was destroyed and Richard Nixon’s was made. He was still around the two men’s careers passed each other in the opposite direction.

It was one of those famous American trials that capture the spirit of its times, and take on broad meaning.

The government accused Alger Hiss of lying to Congress, but only because it couldn’t charge him with treason. A former communist had claimed Hiss had provided the Soviets with classified U.S. documents in 1938, but the statue of limitations protected Hiss from prosecution. So the government charged him with lying to the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

At first, it seemed preposterous. A Post writer described Hiss as a man of “impeccable background”:

“…an official in the State Department, a member of President Franklin Roosevelt’s inner circle, the President’s confidant at the Yalta Conference, one of the chief architects of the United Nations charter and the Secretary General of the United Nations organizational conference … He was a graduate of Johns Hopkins University and Harvard Law School, both with highest honors. He was on the board of the Harvard Law Review. He was chosen as a young man to be secretary to the renowned Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes. Alger Hiss was urbane and flawless in dress. His bearing exuded sobriety, confidence, dedication and aplomb. Not a hair on his head was out of place. There was no ounce of flab on his body. One look was enough to assure anyone that Alger was the essence of the creme de la creme—the very best the elite eastern establishment could produce. Fortunate we were to have a young man of such quality to help guide the affairs of state. And to gild this pure white lily, Alger Hiss was an expert (if amateur) birdwatcher. He could talk with eloquence and enthusiasm about the rare prothonotary warbler, a shy creature with exquisite gold and yellow markings which was a sometime habitue of the swamps of Virginia. No one who really likes birds can intend ill for his fellowman.”

That description was written by Oliver Atkins, a longtime Post employee who is now recognized as one of the great American photojournalists. Atkins worked for the Post until 1968, when he left the magazine to become Richard Nixon’s official photographer.

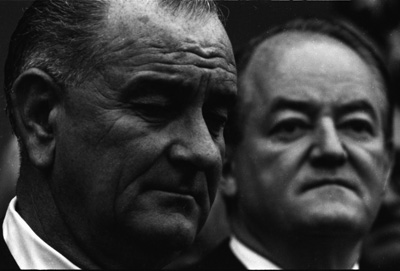

Atkins had photographed every president starting with Truman. He enjoyed working with Nixon—”the best of all the presidents I have known as a subject for photography”—and he admired the man.

They probably knew each other from Nixon’s earliest days in the public eye. In 1948, Nixon was a young Congressman from California and a member of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He pushed the Committee to investigate a suspected communist in the State Deparment: Alger Hiss.

Atkins wrote about the Hiss trial for the Post in 1976. What made the story “timely and meaningful today is that our country is under severe stress in matters of security and espionage.” America had just emerged from several years of hearings, accusations, and investigation into Watergate. Once again, American officials had stolen documents, subverted Federal law, and lied to Congress. Only this time, the accuser, Richard Nixon, was now the accused.

Politics on Trial

It is hard for Americans who didn’t live through those days to understand the importance of this trial. People had grown frustrated in their attempt to find the Americans who were aiding communists. Earlier in the century, it was assumed communists were working among the poor and the struggling labor unions.

In the 1930s, their suspicions shifted to intellectuals. Conservatives suspected that the highly educated progressives surrounding President Roosevelt were shifting the country and its economy toward socialism. Anticommunist sentiments rose sharply after the war, with good reason; Russia had returned to its old job of overthrowing capitalism.

So there was delight among conservative anticommunists when a spy was identified in the State Department. Here, at last, was proof that the Red Menace had infiltrated the power grid of Washington.

Alger Hiss was convicted in 1950 and sentenced to five years in prison. He was released after 44 months. By 1976 Hiss regained his license to practice law. Richard Nixon was barred from legal practice and never tried to reclaim his license. Following his resignation from the presidency and his pardon by President Ford, Nixon spent the year planning ways to resurrect his reputation.

Oliver Atkins died the next year. He left his vast collection of photographs to George Mason University, which now holds over 57,000 of his images.

Richard Nixon passed away in 1994. Alger Hiss outlived him by two years. To the end of his life, he continually maintained his innocence of treason and his loyalty to America.