The Streaming Wars in 2022

While broadcast television continues to hold on, streaming and differentiated viewing grows its audience with each passing year. One stark comparison can be drawn from the Nielsen broadcast ratings numbers from the week of March 14, 2022; the top show, 60 Minutes, pulled in just over nine million viewers. By contrast, Euphoria is pulling in over 16 million watchers combined from HBO and the HBO Max platform. As streaming continues its ascent, the battle for the top of the heap has become more intense, with major platforms making significant moves to cement their place in a rapidly shifting landscape.

Netflix remains at the top of the biggest streamers with an audience that’s nearly 222 million viewers. The remainder of the top services in America are Prime Video, Disney+, HBO Max, YouTube Premium, Hulu, Paramount+, Peacock, ESPN+, Apple TV+, Discovery+, Crunchyroll, Funimation, BET+, and Shudder. Nearly all of them have made news in the past few months with everything from new features to new additions that have people talking. Here are a few highlights.

Stranger Things 4 trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Netflix)

Netflix: While continuing to perform at a high level with outsized hits like The Adam Project, Netflix continues to fall back on complaining about password sharing among customers. Despite being the clear leader in subscriptions worldwide, there has rarely been a four-quarter frame in which Netflix doesn’t discuss a new initiative to stop the shares. Most recently, the service announced that it was going to start charging accounts extra for passwords being used outside the household. However, that program is currently only going into effect in Peru, Costa Rica, and Chile. Right now, the top-tier Netflix subscription allows up to four screens to be in use; many users argue that it shouldn’t matter if all four screens are in the same house, particularly if one of those screens is being used by a child away at school. Such a change could actually upset the balance of subscriptions in the U.S., which is obviously a situation that the biggest kid on the playground wants to avoid.

The Streaming Home of Marvel ad (Uploaded to YouTube by Disney Plus)

Disney+: The House of Mouse just introduced new parental controls that allow for parents to create kids’ accounts that prevent them from watching some of the more mature fare on the service. This is instigated by the arrival of the six Marvel shows that had previously existed as Netflix offerings (Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, Iron Fist, The Defenders, The Punisher) and Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., which ran for seven seasons on ABC. That influx of material added a whopping 184 episodes of new content to the streamer in one day. The parental controls also popped up, in what is certainly no coincidence, in time for the new Marvel series, Moon Knight; while the show is rated TV-14, some early viewers and advance reviewers have noted that the show’s intensity takes it very close to the line of mature fare.

Euphoria Season One teaser (Uploaded to YouTube by euphoria)

HBO Max and Discovery+: The biggest news on both of these fronts is that they’re about to merge. Though the two services were already part of the same company, it was announced on March 14 that shareholders have approved a merger of HBO Max and Discovery+. There is not yet a set date for switchover, nor is there an exact monthly price quote, although there will be different tiers with and without ads. The merger puts HBO Max’s vast library in one place with Discovery’s large well of content, which includes shows from popular channels like Food Network, Lifetime, OWN, HGTV, History, and the Magnolia Network.

Crunchyroll welcomes Funimation and Wakanim (Uploaded to YouTube by Crunchyroll Collection)

Crunchyroll: The extremely popular anime streaming service is battling rumors of a change that isn’t actually happening. Word had been going around that the streamer was going to dispense with free-with-ads programming. That’s actually a misinterpretation; Crunchyroll is moving simulcast episodes (that is, brand-new episodes that debut in the U.S. and Japan at the same time which were running on the free-with-ads tier one week after their debuts) behind their pay structure, but free-with-ads series will still be running. Crunchyroll has a rather unique position in the Streaming Wars; while it has around five million paid streaming subscribers, it has over 120 million registered users that take advantage of free-with-ads use. That puts it below the marquee services for paid viewers, but among the most-watched overall. And that will only get bigger as Crunchyroll is now bringing aboard a huge influx of content from Funimation (creators of the insanely popular DragonBall franchise) and Wakanim.

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds teaser trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Paramount Plus)

Paramount+: To this point, Paramount+ has thrived by being the home of multiple new Star Trek series. With Discovery, Picard, Lower Decks, Prodigy, and the forthcoming Strange New Worlds (which arrives May 5), the service has a lock on that extremely loyal audience. However, they are maximizing efforts with new shows (Halo) and a barrage of reboots and spin-offs, including another Yellowstone series, original movies spun-out from S.E.A.L. Team and Teen Wolf, and revivals of Frasier and Beavis and Butt-Head. At right around $5, it’s a must-have for Trek fans, and a bargain for others with its growing film library (which includes The Godfather trilogy and more).

If there’s one thing that’s certain about our streaming future, it’s that nothing is certain. In the past few years, there’s been a veritable explosion of options. While some were DOA (like Quibi), some have grown beyond their introductory form into something of greater potential, like the evolution of CBS All Access into Paramount+. The consolidation of HBO Max and Discovery+ is no real surprise, as it gives owners a mammoth base. At this point, it seems that the titans (Netflix, Prime Video, Disney+, HBO) will continue to sit at the top of the mountain, but diversity of content and healthy services with a targeted audience (like horror streamer Shudder) mean that there is plenty of room for other entries. As the Streaming Wars continue, some forces are going to take more ground, but it’s apparent that smaller established entries will find a place to survive.

The Streaming Wars: And The Child Shall Lead Them

The Post has been covering the Streaming Wars for some time now. In the past several months, a number of new developments have taken hold. These include services embracing a new kind of Video-On-Demand (VOD) model, some new service launches, and several layers of content reshuffling. HBO Max, Peacock, and Quibi all launched with various problems, while CBS All Access seems headed for a merger with a larger platform. And then there’s The Mandalorian, which barnstormed social media with breakout character “The Child” (aka “Baby Yoda”) on its way to a jaw-dropping 15 Emmy nominations. But what about stalwarts like Netflix? And how does the Age of COVID-19 change the shape of what’s to come? Here’s your war report.

Lockdown on Demand: When theaters closed across the country with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, studios scrambled to change dates and look at alternative delivery formats. One victory was found at the drive-in; the built-in social distancing that comes with watching a film from your car allowed some new releases to filter out, some old favorites to come roaring back, and for some small films to generate (for them) big numbers. One of the first movies that was slated for a big theatrical release, but shifted to a VOD delivery, was Trolls World Tour. The sequel to the hit 2016 animated musical became available for digital rental on April 10 (which was the same day that it debuted in a limited number of theaters), but at a steeper rental price point that would be more akin to taking a family of four to the movies. The film made a startling $40 million off of rentals in its opening weekend. IndieWire estimated in August that it’s made around $150 million in rentals through the life of its release. Other studios have followed suit with select releases. Bill & Ted Face the Music from United Artists bowed in select theaters and for a $19.99 rental across a number of services. In just four days, it was Fandango’s top title for all of August.

The trailer for Mulan. (Uploaded to YouTube by Walt Disney Studios)

However, it looks like Disney+ is in line to have lightning strike twice. The first major mouse move was to bring the filmed version of Hamilton to the service months before it was scheduled to arrive in theaters. The July 3 release spurred a quarter of a million new Disney+ subscriptions that weekend, and Variety reported that roughly 37 percent of all the app’s subscribers watched the musical in its first month. The second big release shuffled to the platform was the live-action remake of Mulan, which debuted September 4. Early indications are that Mulan’s performance may easily surpass Hamilton’s, with one major catch; Hamilton was simply an addition to the platform, whereas you presently have to pay $29.99 to get Mulan. With Disney+ passing 60 million subscribers in August, it would only take 8 percent of subscribers ordering Mulan for the film to clear nearly $150 million. That would be a major victory for the company, and it would make it much more feasible for other delayed blockbusters (like Black Widow) to make a profitable simultaneous home and theater debut.

New Launch Woes: Even as the traditional HBO channel is garnering attention and praise for its new series, Lovecraft Country, the rollout of the new HBO/AT&T/WarnerMedia app HBO Max has been something of a headache. When HBO Max landed in May, it wasn’t available through Roku or Amazon/Fire devices . . . and it still isn’t; the problem is that those two options represent approximately 70 percent of the streaming player market in the U.S., and they’re locked in a dispute with HBO Max over fees. Additionally, roughly 20 million people who subscribed to HBO, and who would have gotten HBO Max rolled in with their sub, simply didn’t activate the service when it started, meaning that HBO Max only had about 4 million official users by the end of June. There was also confusion when HBO’s other apps (HBO Go and HBO Now) went away and were replaced with, simply, an app called HBO. That app offers the programming that Now did, including current series, but doesn’t have access to the Max exclusive series or the wider content libraries (like the Criterion Collection) that were rolled into Max. Confusing content deals haven’t helped; while the Harry Potter franchise and various DC Comics-based films were heavily advertised for the launch, pre-existing deals with other services meant that many of the DC movies vanished in the first week, and the app lost the Potter films in August. The struggling DC Universe app will have its content rolled into HBO Max, but questions linger about whether its extremely popular digital DC Comics library will make the transition or go elsewhere.

Depature is one of many originals headed to Peacock. (Uploaded to YouTube by Peacock)

The NBCUniversal app Peacock kicked off for Xfinity users in April; it landed on other platforms in July and worked up to 10 million viewers by the end of that month. It has a free tier that accesses 15,000 hours of content; the pay levels unlock about 5,000 more. With NBC Sports deals for soccer and content with third-party providers like ViacomCBS and Paramount Pictures on the way, Peacock is putting together a big library, and is looking to Parks and Recreation (arriving in October) and The Office (arriving in January 2021) to boost subs. However, it has one big problem in common with HBO Max: you won’t find it on Roku or Amazon. Peacock also had some of its big launch-day draws, like the Fast & Furious franchise, The Matrix, and Shrek already vanish. New content has taken a hit due to the COVID-19 shutdowns. In the face of these issues, which users have complained about readily on social media, there has also been praise for a “channels” feature that runs clips and content around different themes. The Today All Day channel gathers The Today Show segments, and other channels are devoted to Saturday Night Live and other themes.

Quibi is a mobile streaming platform that launched with free trials in April with an eye toward shorter programming. The 10-minute episodes are referred to as “quick bites” (a phrase that was truncated into the service’s name). While a number of high-profile companies invested in the service and stars like Anna Kendrick and Kiefer Sutherland dot the programming, the download numbers for the app crashed after the first month of operation. The company cut staff in June amid reports that its 2 million subscribers fell well under a proposed 7.4 million user goal. The Verge reported in July that the conversion rate from free initial user to paid subscriber was a poor 8 percent.

A Viacom Mind-Meld: CBS All Access has put together a base of around four million subscribers. The service has bet big on Star Trek so far, with three active series (Discovery, Picard, and Lower Decks) and two coming (Strange New Worlds and Section 3). One much anticipated show is the upcoming adaptation of Stephen King’s The Stand, which launches in December. Like Apple TV+, CBS All Access has been actively gathering other content; parent company ViacomCBS looks to merge All Access with programming from its other brands (MTV, BET, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, etc.) with the notion of competing with the bigger services.

Update: Early on Tuesday morning, September 15, one day after this story originally posted, ViacomCBS announced that CBS All Access will be rebranded in early 2021. Under the new name Paramount+, the service will roll in CBS All Access programming with the other brand verticals mentioned above for a larger, more competitive service.

The Morning Show has been a major success for Apple TV+. (Uploaded to YouTube by Apple TV)

Apple in the Middle: Apple TV+ is doing all right. The streamer already renewed most of its original drama and comedy series and the service claimed 18 Emmy nominations, including nods for The Morning Show, Defending Jacob, and Beastie Boys Story. While Apple had intended for the service to focus on original content, it went into acquisition mode in the middle of the year after COVID-19 shut down original productions. The app actively bought films like Tom Hanks’s Greyhound and Will Smith’s upcoming Emancipation to bolster content offerings. Apple also has a robust development slate for series and films spread across the next few years; it has the potential to develop into destination viewing for unique programming over the long term.

The Big Kids on the Block: Netflix, Amazon’s Prime Video, and Hulu remain the big dogs in the yard, with Disney+ joining the pack. Prime Video is available to Amazon Prime’s 150 million subscribers around the world, though about 26 million actively use it. Hulu has 35 million paid, with over 3 million of those opting for Hulu+Live TV to replace cable service. Disney+ passed 60 million in their first year, stomping their initial estimate that it would take until 2024 to get 60 to 90 million subscribers. Netflix remains the numbers champ, with 193 million paid users.

Each of those services continues to offer strong performances in various areas. Prime’s The Boys has been a breakout critical and commercial hit, and anticipation is high for the forthcoming Lord of the Rings series. Hulu had a big quarantine hit with original film Palm Springs, a strong development slate, and offers returning water-cooler programs like The Handmaid’s Tale. Netflix is, of course, Netflix, and wields enormous programming influence; the primary viewer complaint about the service is the impression that many series don’t get past three “seasons” or that they appear very quick to cancel shows that might grow with more time. Nevertheless, Netflix cuts a dominant figure, especially with the success of films like Extraction, break-out series like The Witcher, and their ongoing live-comedy specials.

The trailer for The Mandalorian Season One. (Uploaded to YouTube by Star Wars)

As for Disney+, its first year has seen a subscription base that exceeded expectations, 19 Emmy nominations, and a legitimate pop culture phenomenon in the form of The Child, the inhumanly cute “Baby Yoda” that co-stars in The Mandalorian. That Star Wars spin-off accounted for 15 nominations, including an unexpected nod for Best Drama. The service also had the good fortune to have The Mandalorian season two filming completed before the pandemic; editing and effects continued remotely, which will allow the next set of episodes to debut in October as scheduled. Additionally, the much-anticipated Marvel Cinematic Universe installment The Falcon and The Winter Soldier is still expected to debut this fall after an initial delay from the COVID shutdown. All of that is, of course, on top of one of the most powerful libraries in entertainment, which includes the Marvel and Star Wars brands, the Pixar films, Disney animated classics, and National Geographic, in addition to acquisitions like Beyoncé’s video album Black is King.

| Service Name | Price Per Month | Program Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| Amazon Prime Video | $8.99 standalone; $12.99 w/full Prime | The Boys, The Expanse, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel |

| AppleTV+ | $4.99 | The Morning Show, For All Mankind, Servant |

| CBS All Access | $5.99 | Star Trek: Discovery, Star Trek: Picard, ST: Lower Decks |

| Disney+ | $7; $12.99 bundled with basic Hulu & ESPN+ | The Mandalorian; The Imagineereing Story |

| HBO Max | $14.99; $143.88 for 1-year deal available | Raised by Wolves; Doom Patrol |

| Hulu | $5.99 basic; $54.99 +Live TV; ad-free tiers also available | The Handmaid’s Tale; Castle Rock; Shrill, Letterkenny |

| Netflix | $8.99 basic; $12.99 standard; $15.99 Premium | The Umbrella Acadmey; Cobra Kai; Lucifer; Away |

The streaming landscape has become a crowded, constantly shifting place. It’s possible for multiple large outlets to co-exist; even with the pervasiveness of Netflix, it’s obvious that several other companies have very healthy options. The big question is how many of these services will thrive in the long term. At some point, every household will hit saturation on the number of services that they actually use, or can afford. Until then, the various entrants will continue to jockey for position in a race that is much more a marathon than a sprint.

Featured image: Ivan Marc / Shutterstock

All the Souls We Cannot Save

Shortly after midnight, Sruly slipped below decks to find himself a snack. He hadn’t been able to sleep since the ship left port. He had taken to eating twice as much, compensating for the lack of one primal activity of self-preservation with another. He peeled himself an orange. The exercise gave him no small amount of joy. The turf sprayed onto his eye as his thumb cut the fat clay skin, leaving with him the sting of that acid burn. It felt good, unexpectedly good, like a blast of cold winter air after a long warm night’s sleep — something he was not likely to feel for another few years, if not longer.

He dispensed with the peel quickly, in one unbroken ribbon, and set to work stripping off the veins of white. He knew they were edible, but something disturbed him about eating parts of an orange that weren’t, well, orange. He was an orange connoisseur. He was an orange purist.

This far into their voyage, the carried-on supply of kosher meat in their cabin had been depleted, and their crackers and canned tuna were running low. The communal supply of oranges was all that were left for Sruly and Shoshana to eat. It wasn’t the ideal honeymoon (at least, not the kind they’d grown up imagining) but each of them minded less than they thought they would. Sruly was brought up a good Brooklyn boy, his teeth weaned on the juicy fat of a thick steak, and so you’d think converting to an all-fruit diet would be unnatural, but you’d be wrong. Sruly was an adapter. He was open to whatever fate had on the menu. He was an improviser. He was on a mission from G-d.

The ship docked at Manaos, depositing Sruly, Shoshana, their luggage, a Torah scroll, and enough food to feed both of them for nearly a year, presuming they could find somewhere to keep it from spoiling, or three hundred people at a single meal. That wasn’t a problem for Sruly and Shoshana. They were both counting on the latter option.

Manaos was a coastal town, nestled between the ocean and a tributary that fed deep into the jungle. Traditionally, the local economy hung on vacationing smugglers, or a ship’s crew who would dock for a few days between runs. Of late, however, profusions of college kids had sprung up, waylaid on perpetual spring breaks. There was also a startling number of Israeli backpackers, fresh out of the army and filled with a newfound mortality, a yearning for nonspecific third-world spirituality, and lumps of disposable savings. Manaos, with its jagged cliffs, steep hiking trails, and shamanic culture, was an ideal destination.

Sruly and Shoshana arrived in early spring. In Brooklyn, trees were still defrosting. Here the world was already exploding into a full-blown summer, a paradise of lush blooms and wet air. Everywhere they looked, wildlife stretched its wings and flexed its claws, the act of creation anew.

They took a room at the Empress Hotel. It was small, but serviceable. They had no money, but big dreams, and lots of plans, and not much time to realize them.

They distributed flyers everywhere they could. Cafes, clothing shops, hi-adventure supply stores and the local tourist bureau. Shoshana set foot in the steam baths, a set of natural saunas that emerged from a geologic peculiarity. The locals had converted it into a spa of sorts, and a profitable business. Tonight was a women’s-only night, and she slipped into her swimsuit without a second thought. She started up a conversation with the woman next to her, a dark-skinned twentysomething wearing nothing but a dog tag around her neck.

“So, I see you are here on a pilgrimage?” Shoshana said in Hebrew.

“Just as you are. Isn’t that right, rebbetzin?” The Israeli girl smiled. She’d picked up Shoshana’s secret right away.

“What made you decide to come here?” Shoshana pressed on, determined to be friendly.

“Why does anyone come here?” she said, laughing hard and lustily. “The nightlife. You could say, I have a thing for monsters.”

“Oh, not me!” Shoshana said. “I’m married.”

The girl smiled tolerantly. She slipped deeper into the steaming pool and half-closed her eyes.

“Rebbetzin,” she said, “why did you come here? To save a few of our poor lost souls, to stop all of Israel from becoming Buddhists and pagans?”

Shoshana raised her derrière to one of the pool’s highest stones and sat straight. She had good posture, and, though most of the time you could never tell beneath her modest clothing, a body formidable in its own right. The Israeli girl raised her eyes, in appreciation, or shock, or both.

“I’m just here to make new friends,” Shoshana said. “Next week is Passover. We’re having a dinner on the first night atop Huanchaca Plateau. I’d love to see you there.”

She spoke fast, and with confidence, and in such a commanding voice that the words, though foreign, cemented themselves in the girl’s head. By the time she finished talking, Shoshana was out of the water, her towel wrapped securely around herself, and she’d moved on to the next pool over.

Meanwhile Sruly went on the local bar circuit, starting a few rounds into every evening, giving the kids enough time to get comfortably buzzed before his appearance. He wore his black hat and his big flowing coat. He inserted himself between two khaki-clad tourists, called to the bartender in the local language. He ordered shots for everyone. “What’re we talking about, boys?” he asked.

“Nothing you want to know about, rabbi.” The first guy to speak had a fat American accent, a puffy meat-fed hand with which he squeezed Sruly’s shoulder. It was friendly, but it tingled. “We’re just here to hunt some rare game.”

“Well now, that’s a coincidence.” Sruly slid in, making himself comfortable. “I’m a hunter of a sort, too. I’m here to hunt for lost souls.”

“Oh, you’ve got to be kidding,” they told him. And I’m a lost cause, they told him, and Just keep moving. He did — he never stopped moving — but not till after he’d made his pitch, and usually not until they’d accepted, however half-jokingly, one of his invitations. He was trying to be a local, but by no means was he trying to fit in. All on his own, he was an enigma. He was a spectacle. The frat guys and the backpackers approached him as if hypnotized, moths drawn to flame. They were no match.

They had two weeks before Passover began. In that time, Sruly and Shoshana spoke with — in their most conservative estimation — no fewer than 500 people. Those people were old and young (but mostly young), American and Israeli and European (but mostly a mix of the first two), religiously Jewish and religiously something-else and I-don’t-know and atheist, but mostly religiously unaffiliated — that is, they hadn’t yet made up their minds. Not everyone came, of course. But an astonishing number did. The assembled company, a combination of friends, traveling companions, hookups, bar-buddies-for-the-week, stray lurkers around the lobbies of youth hostels, captured by the hey-there’s-this-thing-tonight vibe sweeping through town, ascended to Huanchaca Plateau. Where the bush and the nut trees thinned into a meadow, the wandering individuals grew into groups, and the groups clustered into crowds.

Sruly and Shoshana made all the food themselves. The natives perked up at their offer of a modest payment, but flatly refused to travel to the Plateau. And so the young couple had no choice but to buy their own plates and cups and cutlery, folding tables and bridge chairs, and lug all of them out of the city and along the paths. Not only was Huanchaca Plateau picturesque, it was also the only spot they could find for free. They’d poured all their finances into this Passover dinner, their inaugural event, hoping to find a few donors in the crowd, enough to finance the next few months of Sabbath dinners and learning programs and challah-baking classes — to say nothing of their growing hotel bill and the distant hope of setting up a house of their own, perhaps one of the Victorian mansions that still sat on the edge of town, built by white settlers and then abandoned for most of a century. With luck, and with G-d’s help, they could do it.

First, though, they had to get through this dinner.

They used all the food they had brought with them, and then some. They cooked all the meat (they’d stored it in the hotel’s walk-in fridge — yes, they’d had to pay rent on that, too) on a barbecue spit at the edge of the plateau. They collected a breathtaking array of fruits and edible fauna from the jungle around, laid them out in eye-catching platters on each table.

And they’d squeezed their own juice from local grapes, an exhausting procedure, since the grapes themselves were almost uncrackable — the animals in the jungle, they were told, often wrestled with the nutlike skin for several hours before the fruit would yield its juices. It took Sruly entire days to harvest enough, and several times he’d nearly broken his hand. But he had to. It was for the seder, that’s what he kept saying to himself. It was what G-d wanted from them.

Their guests poured in. Their guests sat down to the tables. First one wing was filled, then the next. They set for two hundred; they ended up receiving nearly twice that many. People were generous, and good-humored — they doubled up on chairs, the brickish Israeli soldiers pulling the meek Americans onto their laps; they pulled tree stumps to sit on from the surrounding forest. For the first time since they’d arrived, Sruly and Shoshana breathed easy. Their guests were helping each other, and helping them. The meal would surely be a success.

“Let’s get started,” said Sruly, and said it again, once the crowd had quieted. “We’ll begin with kiddish, the prayer over wine. Please pour for your friends, then for yourself. And would someone please uncover the platters?”

Shoshana heard it first. Before Sruly, maybe before anyone else. Distant, but urgent, first sounding like crickets, then like angry birds. The rustling of the platters. The appearance of first fruits. A few people were starting to look around; a few of the ex-infantry, the ones who were trained to notice such things. When they were closer, they sounded like elephants. But by that time, it was too late to do anything.

They dove down. First they aimed for the platters. At first, they looked like giant birds—their beaks like necks, taking up half their body. Then she saw their skin: reptile.

The caws came louder. The shrieks were on the ground, now. There was a screaming from all directions. Their mouths slashed from one side of their body to the other, their wingspan longer than a car, their beaks able to snatch even farther. They grabbed whatever was closest—fruit, meat, human.

Shoshana snatched her husband’s hand — he was standing still, petrified — and ran.

At first the press was on their side. They were newlyweds, putting on a dinner for strangers, giving of themselves, out to make a new life in a lost world. Soon, though, they stumbled upon the religious angle, calling them fundamentalists and missionaries and other barbs of zealotry, anything to keep the focus on the lives lost.

And it wasn’t that many lives, either. Of the 321 people at the meal (the journalists loved that number, 321 — it was like a countdown), nearly 300 were saved. Sruly and Shoshana were personally responsible for several dozen rescues, shooing people into the cave where they’d stored extra supplies, throwing rocks at the monsters, who were trying to snatch up more than they could chew. They’d both needed extensive therapy after that night, but the closest thing to a therapist in Manaos was this old yoga practitioner from Berkeley who’d moved here during the ’80s. The natives called her Mother Tho. She was at least seventy years old and she practiced a local form of transcendental meditation. While talking to her, Sruly learned that her birth name was Barbra Rosenblum. They invited her to dinner the following Friday night.

The hotel kicked them out. They couldn’t handle the influx of paparazzi; the noise was getting to the families, and Sruly and Shoshana couldn’t afford to stay there much longer, anyway. They found housing, first at the local youth hostel, then in a ragtag block of slum apartments. Toward the end of their first year, they moved into one of the old Victorians on the edge of town. A local donor sponsored rehabilitation of the decimated rear walls of the house. They covered the rear walls in iron.

Another thing that happened at the end of that year was their first baby. Around this time, there was a resurgence of press — the one-year anniversary of any tragedy was a wound easily punctured — but this time, they were prepared for it. Besides, they were too religious to have a television or internet. And, for that moment, the memory faded.

Life crept in. The harrowing moments get lost in a sea of other moments, less emotional but more numerous and, in every individual moment, more pressing. At times, the attack felt like something that had happened to someone else, on some other island. The urgency with which Shoshana pulled her husband away from the plateau seemed insignificant compared to the urgency with which her groceries needed to be cooked up before sunset, the urgency with which the twins demanded to be nursed, the urgency of just needing to get out of bed.

But: they stayed. Against every impediment, against her every expectation, they were still here. It was remarkable to her how life kept moving, even when you didn’t keep nudging it along.

Sometimes she received letters from those people, or their families. The ones she saved, or, more often, the ones she didn’t. Why didn’t you choose my son? one mother wrote to her — in Hebrew, which she could have pretended not to understand. But she couldn’t have. She was not that type of person, not anymore. Other people accused her of not trying hard enough; of not doing due research; of being foolhardy in coming to this country in the first place. This particular mother did none of those things. This mother wrote that she, Shoshana, was her proof that there was no G-d. If there was, she wrote, Shoshana would have chosen to save her son above someone else. It was dumb luck, bad luck, that caused him to be attacked, him and not someone else.

Shoshana replied to all of these letters. She poured ages of her time into each letter, spending hours when she should have been trying to meet new tourists (there were some, even the season after the attack, and growing in number each year after it), buying international postage even when she couldn’t properly afford to. She meditated on each reply for hours, sometimes days, before responding. To this mother, she wrote: Nothing in this world is luck, and each moment is preordained. We don’t know why G-d does what G-d does. That day was so confusing to me. I still don’t remember what I saw, and it gets less clear each day. Did I see your son killed? Did I see him in the back, battling off the creatures as others ran, saving ten others by sacrificing himself? In that space of not knowing, the truth could be anything, literally anything. You can say with certitude, he might have died a hero, and know that could be true. It’s a gift that not many other people have. It’s probably not a gift that you want — it’s not what I would want for my own children — but it’s the gift you are given.

Her own children left Manaos, carried on boats to planes, then from planes to yeshiva. In New York they studied, turned into rabbis and rebbetzins themselves, lived in the world that Shoshana and Sruly had left behind. What experiences they were having, Shoshana could only guess. It was a blind spot of her own. She assumed and prayed for the best.

She tried hard to keep them away from the island. All her children had wandering spirits — it was something they’d inherited from both of them — and she would not have them venturing up to the plateau, seeing what was up there. When they were children she had the ability to rein them in, and when she found she could no longer do that, she redirected their misbehaviors: always to the town below them, never to the jungle behind the house. When they reached that age when their peregrinations were guided not by mischief but by the heart, that was the age when she sent them away.

The children married off, one by one, dispersed to their own corners of the world. From time to time they returned, at first to check up on their parents, then to assist them, and then to see if they could take over. Sruly and Shoshana still held meals for Sabbaths and holidays, none quite so lavish as the first year’s, and all of them indoors. Sruly still led the meals, but he had trouble lugging out the tables, setting out all the dozens of plates and cutlery. Their oldest son flew in more and more frequently. He spoke openly of wanting to take over.

Then came the stroke. After it, Sruly was a changed man. He still led the dinners with the same enthusiasm, still spent his voice on Sabbath songs and the little speeches lined with jokes, just short of improper, to surprise and delight the young people who listened. But he began to take long walks, and she feared which direction those walks led.

There is talk of a reunion. One of the villagers tells her, someone with internet. She wouldn’t have believed it. Most of the people they’d saved were older than they were. Most of them probably weren’t alive. But a representative of the group contacted them by mail, asked if they’d be willing to host a Passover dinner. She surprises herself by not even asking Sruly — she knows what he’d say, and she knows she would overrule him — and saying yes.

There weren’t nearly as many people this time. Forget the ones who died that day. Many more were dead now, dead or unable to travel or simply unwilling. But people did come. She couldn’t understand why. After a life spent here, she understood the central paradox of her strange mission: it was her job to waken the sleeping spirit of inspiration, to talk to people who existed by nature with a different set of basic assumptions than she and Sruly did.

They did start showing up in the village. Sitting outside at the cafes, walking the beaches, emptying their money once again into the paltry tourist shops. And when they came, there was something about them that she recognized, something different than the usual seasonal tourists — something about their faces that didn’t change, their taste in clothes, something she couldn’t lay her finger on. She searched in their faces, wondering if it was mutual, but finding nothing.

The meal started like other meals. Her husband led them in the singing. She brought him wine. She brought the karpas, the fresh vegetable for the ritual; it was a fist-sized vegetable they found among the local flora, fist-sized, a color between olives and combat fatigues. Sruly’s hand stumbled, trying to peel it. She took it from him, sliced it open with a nail that was sharp from years of cultivation. The juices dribbled out, and she watched him eat it, slow and with doubtful teeth. He took pleasure in each unguarded slurp, and she took pleasure in watching him.

They went around the table, asking the Four Questions, Sruly pointing out that it wasn’t four questions at all, but one question with four reasons why the night was different, asking what these questions had to do with the festival anyway, how did these words represent freedom from slavery in Egypt. And then something in his voice cracked — something she hadn’t heard him sound like for a long, long time — and he began to sing another song, something low and pained and deep, and she remembered it as the last song he’d sung that day, the special tune he’d used for the prayer over wine.

She excused herself. She left the table suddenly, laying one withered hand on her son’s shoulder — he got up with her, ready to follow her — using her meager strength to push him back down. She made her way out the sealed-up back door, using a trick only she knew, shutting it securely behind her.

The rush of humidity struck her. Sruly needed the house dry, a condition of his lungs, and outside she found herself swimming through coolness and tangles of vines. This jungle, so close, and yet she almost never saw it. Rarely, on late afternoons when the guests were away and her husband was resting, when she needed to remind herself that she still believed, when she wanted to double-dare her Creator.

A few minutes into the jungle, she heard a rustling behind her. She turned around. There was someone, another woman, using a walker. It was a slim path, with unsteady, tapering gravel, and it wasn’t a very good choice. But she wasn’t going to stop anyone. She turned around. It was the Israeli woman, the soldier.

The woman reached into her shirt and pulled out a set of dog tags. “Remember me?” she said.

“Of course I do,” said Shoshana.

“I knew you’d made it out,” said the soldier. “I read about you on the news.”

“I knew you made it, too. I just know things sometimes.”

“Did you know you made me this way?” The soldier reached up, touched her hair, and Shoshana saw that she was wearing a wig.

Against her will, Shoshana felt herself blushing. “Was it because we saved you? My husband?”

“You saved me by being so goddamn Orthodox,” she said, and she said goddamn in English, it sounded so strange coming out of her Israeli mouth. “I hated how religious you were, how you thought you knew more about me than I did about myself. I swore up and down I wouldn’t come to your meal. I was so mad at you people being here, I told myself I would leave the country that night. And then I did, and then I read about you in the paper. I saw your picture,” she said, and shook her head. “After that, everything happened naturally.”

“We should turn back,” said Shoshana.

“Do you come here often?” said the woman.

And Shoshana smiled, the kind of smile that she herself didn’t know what it meant — something special, something wicked.

“I haven’t,” said Shoshana, “not yet.” She moved aside to let the woman ahead of her on the trail, and she held onto the walker to support it. Shoshana held her steady, one hand on the other woman’s hip. They pressed forward together. Ahead of them were distant cries like crickets.

Featured image: The Brook by Paul Cézanne

No Sweat Tech: Buying from Amazon: 3 Steps to Find What You Need and Avoid Fake Reviews

December is inarguably the big shopping season. All the holidays, the year-end bonuses (if you’re lucky), the scramble of shopping that ends up in the pile of presents.

But April and May? I call that the mini-shopping season. The graduations. The proms and school functions. Mother’s Day. And, if you’re really organized and forward-looking, Father’s Day.

While retail still offers doorbusting sales and holiday specials, more and more shopping is being done online, specifically on Amazon. Even if you end up buying an item somewhere else, you might check the reviews on Amazon first. That’s a good strategy; I’m a big believer in researching products before buying. But shopping on Amazon comes with its own problems and pitfalls.

Amazon’s Dangers

As one of the most popular shopping sites in the world, it’s no surprise that Amazon has attracted its share of crooked dealings and fraudulent schemes. Amazon has recently admitted to a problem with counterfeit goods being sold through its third-party merchants marketplace. The site also has a problem with fake reviews being posted for products. It’s so bad the FTC is getting involved.

Counterfeit goods? Fake five-star reviews that might be hiding the major flaws of a product? What should be a fun online shopping experience turns into a dangerous excursion when you can’t trust what you’re seeing.

If you’re ready to make a big purchase on Amazon, you can take some of the stress off by going through three steps to research both the product and reviews of the product. Buying online is always going to involve a little risk — after all, you can’t see “in person” what you’re purchasing. But a little due diligence will mitigate a lot of potential problems.

An Amazon Shopping Example: The Tale of the Toaster Oven

Let me tell you about my husband’s toaster oven.

When my husband and I got married, he had a toaster oven and I didn’t. So we use his toaster oven. The problem is that his toaster oven and I loathe each other. Whatever I put in it always seems to come back as charcoal. And the temperature and timer have been getting less reliable as the years go by. We’ve finally agreed that it’s time to retire the old toaster oven to the recycler and get a new one — possibly from Amazon.

Before I start shopping, though, I make sure I know what I want: a fairly large toaster oven, with dials instead of digital controls, and not more than $100.

Step 1: I Get My Basic Data

I start with clear parameters because of the breadth of Amazon’s offerings. A simple search for toaster oven brings 6,000 results! If I don’t have at least a general idea of what I want, I’ll get lost in those search results. As it is, there are a bunch of results I can dismiss off the bat — they have digital controls, they’re small, or they’re way out of my price range.

Eventually I find a toaster oven I like — a BLACK+DECKER TO3250XSB. Not sure why it sounds like a race car, but there you are. It’s got room for eight slices of bread, uses dials instead of digital controls, and is less than $70. Perfect. Now I start my due diligence by asking three questions.

Question 1: Where’s the Item Shipped from?

When you shop on Amazon, you might buy an item directly from Amazon, or you might buy an item from one of the merchants that sells on Amazon’s web site. Those merchants can deliver items to you in one of two ways — FBM or FBA.

FBM means “Fulfillment by Merchant.” The merchant will ship the item to you directly from its warehouse. FBA means “Fulfillment by Amazon.” The merchant sends the item to one of Amazon’s warehouses, and Amazon takes care of stocking it and shipping it to you.

Most Amazon merchants are honest and want to give you a good shopping experience. But some aren’t. When you buy an item from a third-party merchant on Amazon and the merchant ships it to you directly (FBM), Amazon never sees it. It might be counterfeit. Items shipped FBA have somewhat better quality control because Amazon carries the item in its warehouse. If you’re looking for an item that’s in an oft-counterfeited category — things like fashionable clothing, makeup, and women’s accessories — you will eliminate a lot of risk by either buying just from Amazon or using a merchant that fulfills orders via FBA.

Question 2: What Are People Asking About This Item?

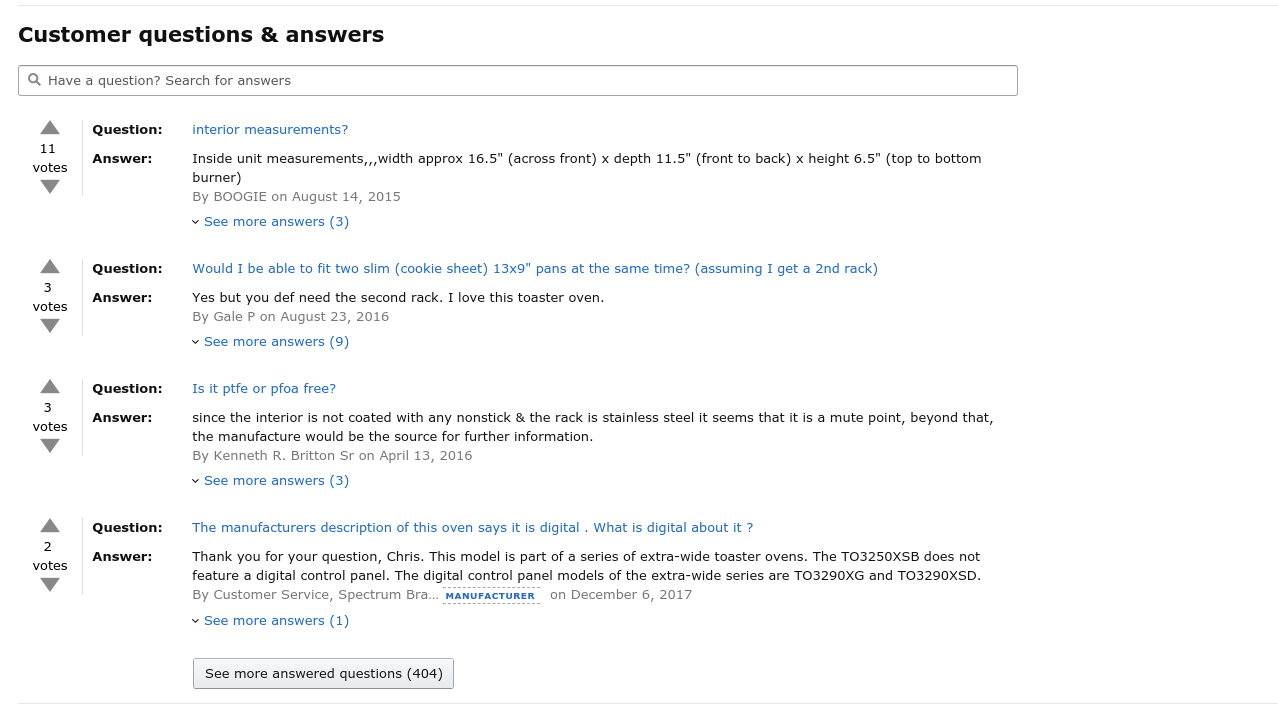

On about the middle of every Amazon product’s page is a bunch of questions that have been asked and answered about that product.

I always check that for two reasons. The first because I want to see if there’s anything I missed when thinking about the product. In this case customers asked if the interior of the toaster oven was coated with Teflon, something I hadn’t considered. (It doesn’t appear to be according to people who have purchased it.) Second is to see if the manufacturer responds to questions. I take it as a good sign if the manufacturer or seller responds promptly to questions with clear, easily understood answers.

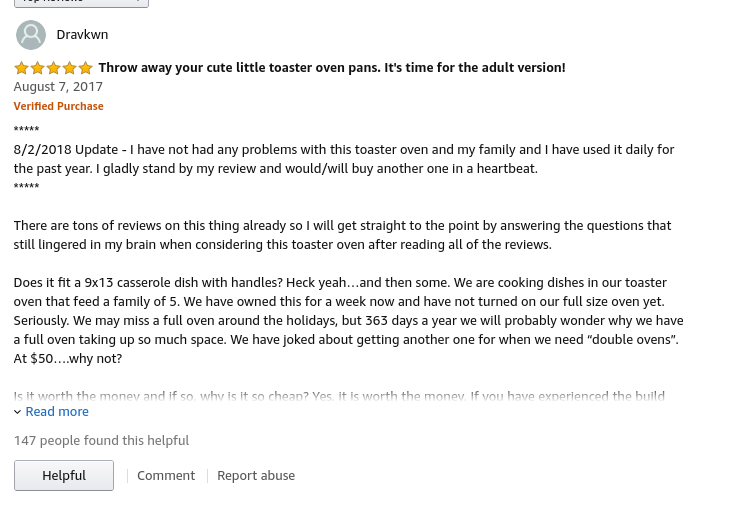

Question 3: What do the reviews say?

Amazon has two types of reviews: regular and verified purchase. A verified purchase review means that Amazon has confirmed the user purchased the item on Amazon and also that the user did not get a steep discount on the item. Verified reviews have a little orange “Verified Purchase” underneath the date of the review. Unverified reviews might be fraudulent, purchased or planted by the seller, or given in exchange for free products or even money. (The BBC recently interviewed two people who fake online reviews. One of them even fakes verified reviews! Nothing is completely trustworthy, unfortunately.)

Unverified reviews might be useful (I leave reviews on Amazon for books I’ve bought elsewhere all the time), but with verified reviews you know you’re reading a review for a purchased product, and that review is more likely to be honest. Dishonest sellers might attempt to game the review system, but it’s more difficult to do that with verified reviews.

Amazon makes it possible to see only verified reviews, but it’s a little tricky to find. If a product has any reviews, some of them will be on the product’s page. Down at the bottom of the reviews you’ll see a link that reads something like “See all 1,594 reviews” (in the case of this toaster oven). That will take you to a page of reviews for the product, along with a set of filters that allow you to see just verified reviews.

Take a glance at the verified reviews. Are they very much different from the mix of verified and unverified reviews? (If they are that’s a red flag.) Are there only a few verified reviews and lots and lots of unverified ones? Don’t try to read them all, just skim a few for impressions.

I took a look at the verified reviews, and they’re a confusing mix of five-star and one-star, but the pros seem stronger than the cons at the moment. I’m sticking with the toaster oven. Now I need to look more closely at the reviews.

Step 2: I Dig into the Reviews

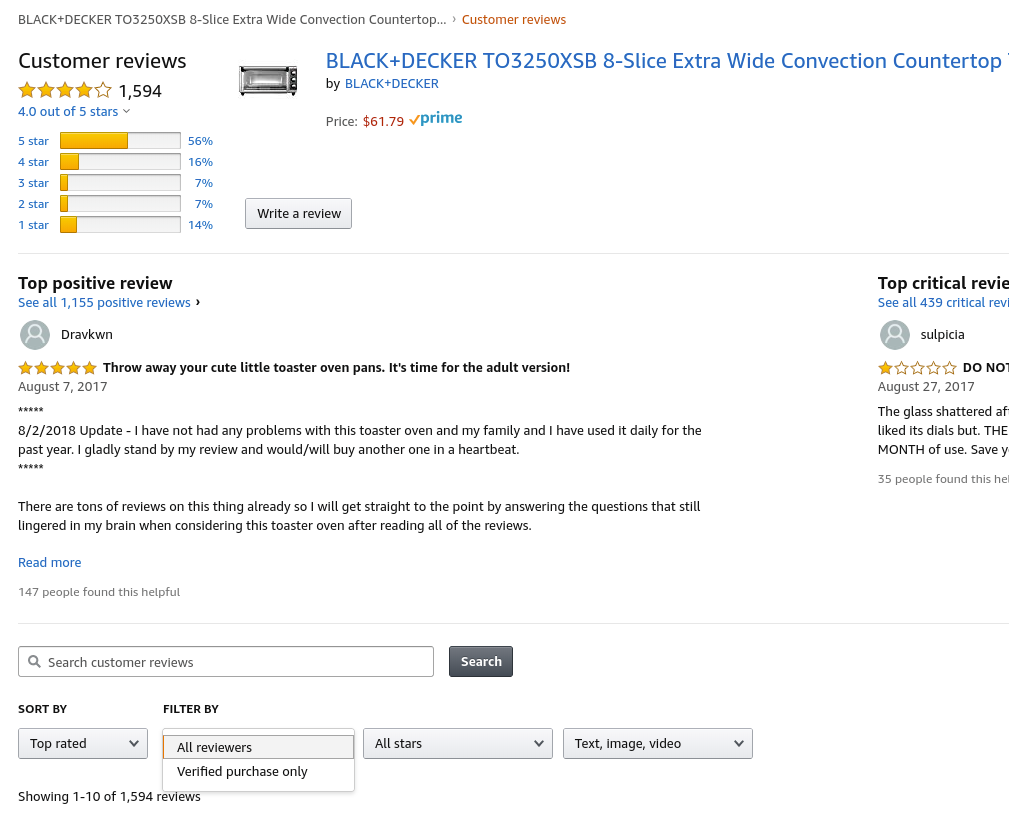

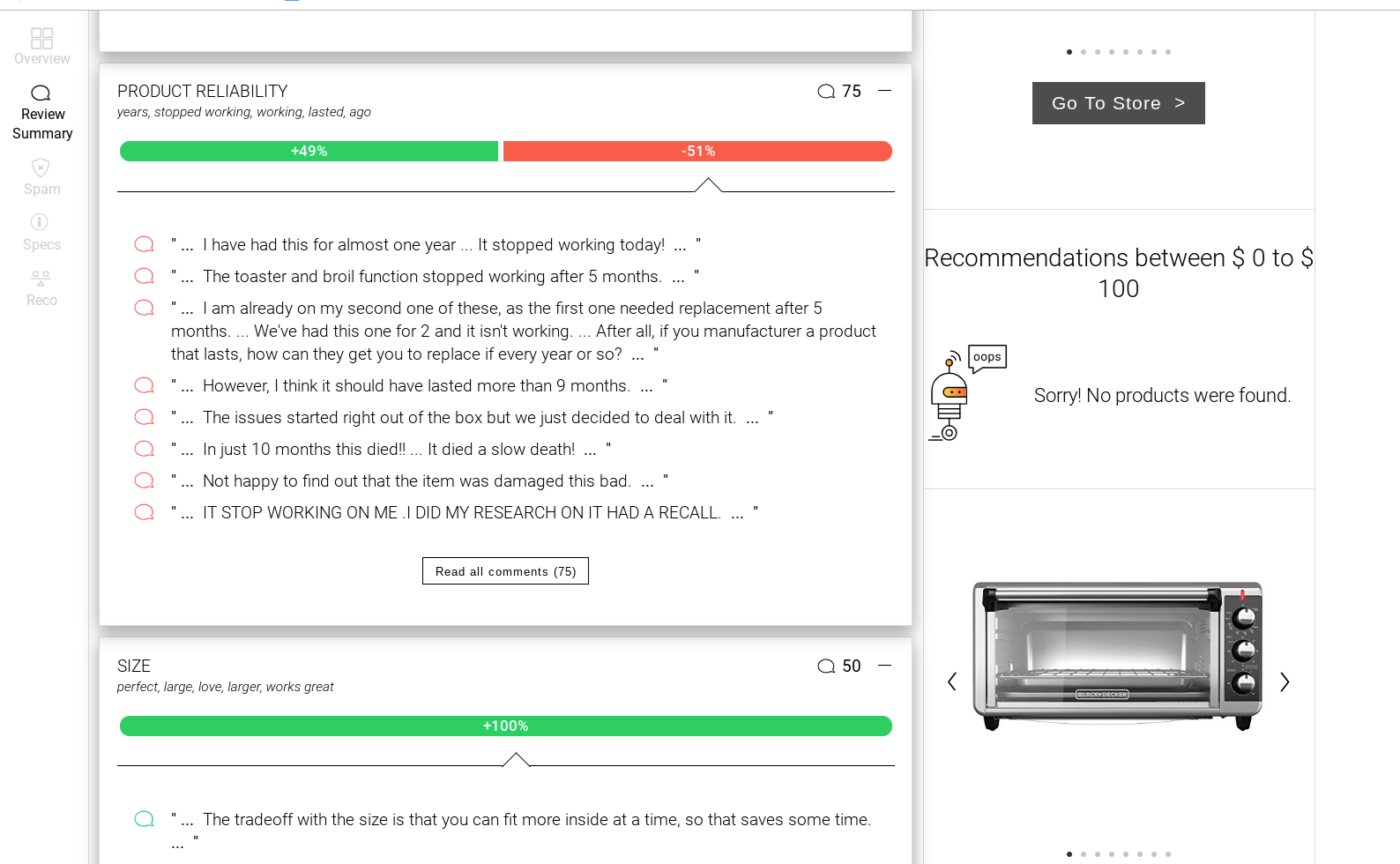

This toaster oven has almost 1,600 reviews on Amazon. Even if you eliminate the unverified ones, it still has almost 1,500 reviews. I’m not reading 1,500 reviews. Fortunately, I don’t have to because there’s an online tool to help me out: The Review Index Review Summarizer.

The Review Index takes the URL of an Amazon product page, digests recent reviews, and spits out a series of summaries based on different review topics, noting whether the summaries were in general positive or negative.

In this case the reviews were mostly positive, but I’m concerned about the fact that product reliability was an issue in several reviews, with reviewers complaining that the product failed after a fairly short period.

Okay, after going through the review summaries, I’m still in favor of this toaster oven (though I’m seriously considering an extended warranty).

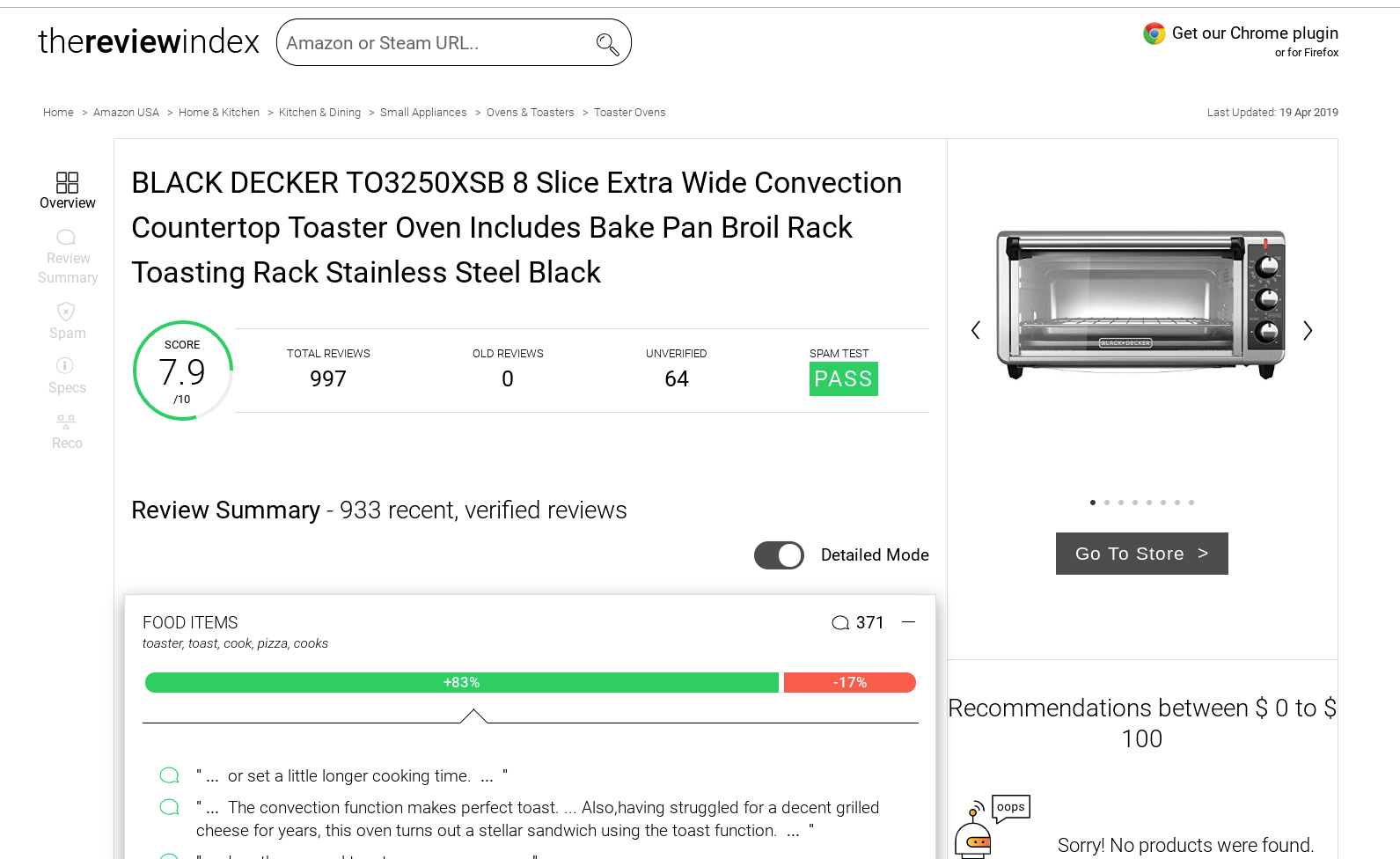

Step 3: I Double-Check the Reviews for Fraud

Finally, I want to do one more pass and look for fraudulent reviews. As I’ve already noted, Amazon has a fraudulent review problem. If an Amazon product has an overwhelming number of fraudulent reviews, that’s enough of a red flag for me to skip purchasing.

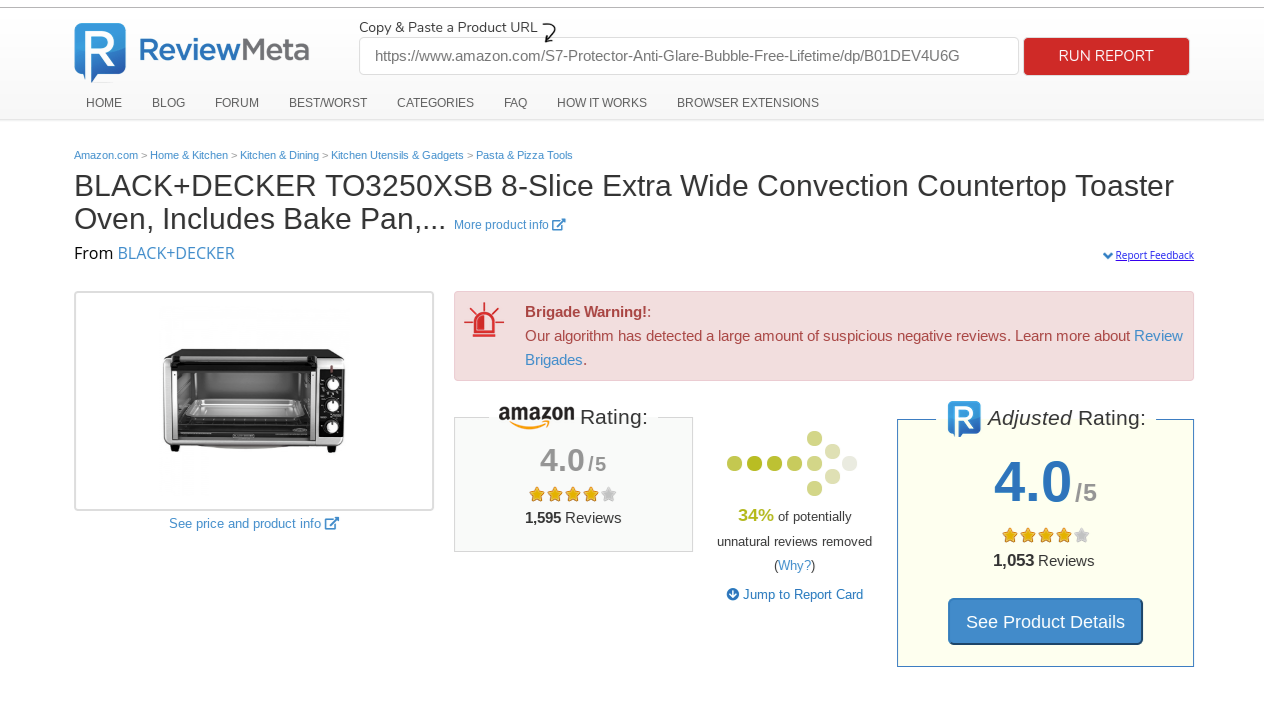

That’s why I’ll use one more tool to check the reviews and see if there’s any funny stuff going on. It’s called ReviewMeta.

ReviewMeta works a bit like The Review Index, where you put in an Amazon product URL and it draws certain conclusions. But instead of summarizing the content of the reviews, ReviewMeta is looking for fraud and patterns of fraud.

Ah, that’s interesting! ReviewMeta has found what it believes to be a pattern of fraudulent reviews, but they’re fraudulent negative reviews, not positive. ReviewMeta goes through not only the review but the reviewers, looking at their average rating, other things they’ve reviewed, and how they review, to give the reviews on the product page a score in several categories.

It takes a little time to go through the entire ReviewMeta report, but I’m not seeing lots of red flags here. There are some deleted reviews, but when considered as a ratio of the overall reviews it’s not bad.

You might be thinking this is a lot of work, and it is. Whether the work is worth it is up to you. If you care about someone enough to get them a gift, you want it to be the best gift possible. If you’re buying something for yourself, you’ll probably want to use these tools for items that are more expensive or those that will be heavily used. My husband and I both like toast and we’d like to get a good toaster oven I get along with that will last for a while, so I have no problem carefully choosing one. On the other hand, you might not want to check out a product this thoroughly unless it was, say, over $200.

Vetting substantial purchases I make on Amazon (and as I just noted, definitions of “substantial” can vary) has become a habit for me. Once you get used to quickly looking at where an item comes from, skimming through the questions, and getting a sense of what the reviews say, it becomes a fast process with a big payoff: getting the most from your money — and avoiding product returns!

Featured image: Shutterstock

10 Best Winter Reads

Fiction

The Dreamers

by Karen Thompson Walker

A mysterious illness causes people to fall into perpetual sleep in this eerie and beautiful novel by the author of the best-selling Age of Miracles.

Random House

The Current

by Tim Johnston

In this thoughtful yet driving mystery, two young women plunge into a Minnesota river, but only one comes out alive. As she investigates, the layers peel back chapter by chapter.

Algonquin Books

That Churchill Woman

That Churchill Woman

by Stephanie Barron

Winston Churchill’s American-born mother is the subject of this historical novel that reads like The Paris Wife meets PBS’s Victoria.

Ballantine

The Silent Patient

The Silent Patient

by Alex Michaelides

People will be talking about this debut thriller about a wife and husband with a seemingly perfect life, a shocking murder, and a therapist obsessed with uncovering the motive.

Celadon

Black Leopard, Red Wolf

Black Leopard, Red Wolf

by Marlon James

The Man Booker Prize-winning author has written an African Game of Thrones, the first in a trilogy.

Riverhead

Nonfiction

Dreyer’s English

Dreyer’s English

by Benjamin Dreyer

Could this be the next Eats, Shoots & Leaves? Language lovers will cherish this witty guide to proper writing by Random House’s longtime copy chief.

Random House

Wild Bill

Wild Bill

by Tom Clavin

He was literally a living legend, the first lawman of the Wild West, and this is his definitive biography by the bestselling author of Dodge City.

St. Martin’s Press

The Unwinding of the Miracle

The Unwinding of the Miracle

by Julie Yip-Williams

When the author was diagnosed with terminal cancer, she set out to write her story for her two girls, creating this vibrant exhortation to live life truly, openly, and bravely.

Random House

Inheritance

Inheritance

by Dani Shapiro

In 2016, the author submitted her DNA to a genealogy website and learned that her father was not her biological father, setting off this memoir about identity, paternity, and family secrets.

Knopf

Maid

Maid

by Stephanie Land

This surprisingly beautiful, moving, and levelheaded memoir explores the contrast of a woman trapped in poverty while working as a maid for upper-class America.

Hachette

The Amazon Effect

Yesterday I went online and bought a Wallet Ninja. I hadn’t realized I needed a Wallet Ninja until a week ago, which is when I read that it’s among Amazon.com’s 10 best-sellers. When a company that lists some 565 million products in the U.S. market announces that the Wallet Ninja (imagine a credit-card-shaped Swiss Army knife) is a runaway hit, count me in. Gotta have one.

Does that suggest I am an easy mark or weak or lazy? Yes. Especially the lazy part. Like millions of others who routinely shop at Amazon’s sprawling website, I am complicit in its takeover of America and all we proudly stand for: unbridled consumerism.

Everyone I know seems to be an Amazon patsy (aka customer). Devotees cut across every religion, political affiliation, and lifestyle. (Some argue that shopping at Amazon is a lifestyle.) The upshot is that Amazon is the least exclusive club in the country but, in some ways, among the most powerful.

To the chagrin of authors, lawyers, and visibly agitated consumer advocates, Amazon has grown into a corporate behemoth. By helping set prices for its vast array of merchandise, it can influence consumer trends as well as broad cultural preferences. And indeed there are potentially dangerous social implications in this. No other web retailer has that kind of clout. Walmart.com claims less than 4 percent of the e-commerce market in the U.S., to Amazon’s nearly 50 percent. Amazon is truly the octopus that swallowed our civilization whole.

Amazon is truly the octopus that swallowed our civilization whole.

Because the company admits it is almost insanely focused on numbers, let me share a few: It did $258 billion in sales in 2018. It’s on pace to become America’s largest clothing retailer by 2021. A year later, the company’s private-label brands are positioned to reach $25 billion in sales. Its annual Prime Day is now tantamount to a national holiday, with more than 100 million products sold to Prime members over a 36-hour period. (Employers take note: 60 percent of that shopping is done from work.)

The truth is that Amazon dominates online sales not only because it’s got everything you could ever want just a click away, but rather because — well, yes, it’s because of that just-a-click-away thing. It’s what in the biz they call “frictionless.” If I want a box of metal paper clips, I can pick them up at any stationery store. But what if I prefer them in teal? Am I going to drive around searching for those? Ain’t gonna happen. I’ll order from Amazon — maybe not at a great price, either, because teal-colored clips are, y’know, scarce. But I’ll have them in a few days. One click.

That means that a store somewhere in my ZIP code has lost a sale, right? Actually, no — because that store probably no longer exists, thanks to Amazon. Retail shops across the country have been slaughtered by the company Jeff Bezos created.

Adding insult to injury, Amazon is now devoting some of its huge cash pile to building its own stores — actual physical buildings in places where there had once been locally owned establishments. Amazon Books, for example, is rolling out as I write. If this sounds to you like dancing on a grave while selling the deceased’s funeral program for profit, you get the point.

But wait, there’s more! The company is currently launching two specialty marts: Amazon 4-star and Amazon Go. An Amazon Bank is rumored. The secret sauce in each instance is extreme convenience, playing to our desire for pampered lives. Amazon Go locations will not even have sales clerks. Or checkout registers. Or scanners. Just stroll out, thief-like, with your bagged goodies. Sensors will invisibly collect codes and bill your account.

Disgusting. No human contact. No warmth.

I’m in.

In the last issue, Neuhaus wrote about his actual neighbor, Mister Rogers.

Top 10 Books for Holiday Giving

Fiction

Nine Perfect Strangers

by Liane Moriarty

In the latest novel from the author of Big Little Lies, nine strangers gather at a health resort, and all leave changed.

Flatiron Books

Paris Echo

by Sebastian Faulks

The past and the present collide as Hannah, an American historian studying WWII in Paris, takes in an Algerian teenager as a lodger.

Henry Holt

The Feral Detective

The Feral Detective

by Jonathan Lethem

The author’s first detective novel since Motherless Brooklyn is set in Los Angeles and features the quirky characters, as well as the zigs and zags, his fans expect.

Ecco

Once Upon a River

Once Upon a River

by Diane Setterfield

A mysterious girl pulled from a river in an English village is at the center of this spellbinding novel about science, magic, and the stories we tell.

Atria/Emily Bestler

The Dakota Winters

The Dakota Winters

by Tom Barbash

In a classic New York family saga, 23-year-old Anton Winters returns to his family home in Manhattan’s famous Dakota Building in 1979 to try to save his father’s waning career.

Ecco

Nonfiction

Becoming

Becoming

by Michelle Obama

A personal, intimate account of the public and private experiences that shaped the former first lady.

Crown

Churchill: Walking with Destiny

Churchill: Walking with Destiny

by Andrew Roberts

The author of a stunning biography of Napoleon turns his eye toward the great English leader, using extensive new historical documents.

Viking

Gene Machine

Gene Machine

by Venki Ramakrishnan

The Nobel Prize-winning biologist tells the riveting story of his race to discover the inner workings of biology’s most important molecule.

Basic Books

Big Week

Big Week

by James Holland

The noted historian chronicles the massive WWII Allied air battle to decimate the Luftwaffe, through the experiences of those who lived it.

Atlantic Monthly Press

Art Matters

Art Matters

by Neil Gaiman

“The world always seems brighter when you’ve just made something that wasn’t there before,” Gaiman writes in this collection of four essays about the power and importance of art.

William Morrow

Adventures in the Kindle Trade

Six months after Maurice Sendak died in May 2012, The Believer published an interview British journalist Emma Brockes had done with him. She asked him his opinion of e-books. “I hate them,” Sendak responded. “It’s like making believe there’s another kind of sex. There isn’t another kind of sex. … Even as a kid, my sister, who was the eldest, brought books home for me, and I think I spent more time sniffing and touching them than reading. I just remember the joy of the book, the beauty of the binding.” [Read the related article “A War on Writers?” by Steven Slon from the Jan/Feb 2015 issue.]

I know the feeling. I too grew up holding, fondling, and smelling books. When I got older I began collecting them. I’ve spent hundreds, probably thousands, of hours hunting down books of writers I’ve gotten to know. When I began writing books of my own, there was such a thrill to see them in print. I will never forget walking past the Madison Avenue Bookstore in Manhattan the week my Conversations with Capote was published in the winter of 1985. It was my first book. And there it was. It was, to say the least, a very special, very personal moment.

My books — my own, and all the others I’ve collected — mean a great deal to me. But I no longer hold the opinion Mr. Sendak did. I don’t hate e-books. I can’t, because my last seven books have been — I hate to admit — e-books.

When Ann Patchett, best-selling author of Bel Canto and State of Wonder, and the owner of an independent bookstore in Nashville, Tennessee, was asked her opinion of e-books, she said, “I care that you read, not how you read.”

I care too. I care very much. The 11 books I am currently reading weigh 19.5 pounds; in my Kindle they weigh zero — that alone makes a good case for e-reading.

“The recent contractions and consolidations in the publishing business — layoffs, dwindling sales and advances, mergers of houses once thought unassailable — have left a widespread sense of unease about the durability of books,” Giles Harvey wrote in a recent New Yorker article about why failed novelists turn to writing memoirs about their failures. “Reading in bed with his girlfriend, novelist Benjamin Anastas wonders if the rise of e-books ‘will help keep writing alive and well into the digitized future, or if my problems are an early warning that my profession is about to go extinct.’”

I don’t think books will go extinct. More precisely, it’s become a changing art. According to the book research firm Bowker, self-publishing now accounts for more than 458,564 books annually, with Amazon leading the way. E-books cannot be ignored. The new problem is how to separate the good from the bad and the ugly.

In the April 2013 Wired, Evan Hughes wrote, “After centuries in which books and the process of publishing them barely changed, the digital revolution has thrown the entire business up for grabs. It’s a transformation that began with the rise of Amazon as an online bookseller and accelerated with the resulting decline of the physical bookstore. But with the shift to e-books — which now represent upwards of 20 percent of big publishers’ revenue, up from 1 percent in 2008 — every aspect of the existing framework is now open to debate: how much books will cost, how long they’ll be. … The only certainty is that the venerable book business, a settled landscape for so long, is now open territory for anyone to claim.”

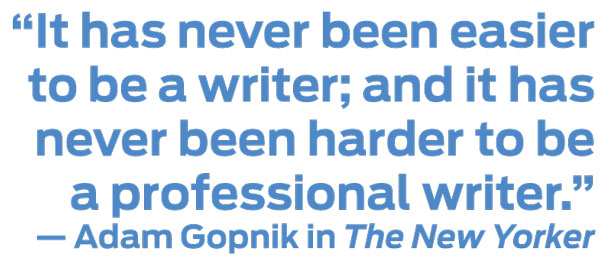

Adam Gopnik, writing in The New Yorker, expressed a similar sentiment. “Thanks to the Internet, the disproportion between writerly supply and demand, always tricky, has tipped: Anyone can write, and everyone does, and beginners are expected to be the last pure philanthropists, giving it all away for the naches. It has never been easier to be a writer; and it has never been harder to be a professional writer.”

It has always been hard to be a professional writer. And yes, it’s a lot harder today. When I started writing books, I received an advance from a publisher that allowed me enough time to write the book. It was never a great deal of money — I got $50,000 for the first book, and $215,000 was the most I ever got, but that book (The Hustons) took me three years to write. Thankfully I was able to supplement my income by writing for magazines, until that world began to shrink as well. So the challenge is to continue being a professional writer — i.e., a writer who makes a living from his writing — in an e-book, self-publishing world. That was the quandary for most of the writers I knew. The only way to find out was to jump in. If I wanted to write what I wanted to write — novels, satire, poetry, memoirs — I would have to test the waters by sticking my own feet in them. I made an investment in myself. And a deal with Amazon. Would it turn out to be a deal with the devil? Or with my savior?

I’m not alone. Name writers like Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, and David Mamet have all put out e-book originals. But, as Bruce Miller, president of Miller Trade Book Marketing warned, “Celebrity authors may have great luck self-publishing, but most authors are not famous.”

Amazon has added a new twist to this market by hiring an editor, David Blum, who carefully selects Amazon Singles, original works of 5,000 to 30,000 words of both nonfiction and fiction. He gets more than 1,000 submissions a month and has published 345 Singles in the first two years of the program. Approximately one-third of these have sold at least 10,000 copies, at an average of $2 per Single. As the writer gets 70 percent of this, it’s understandable why so many are trying to make the cut.

But the truth is, with every successful e-book writer’s story, there are hundreds of thousands of failures. “There are so many stories out there about people who have made it big self-publishing,” literary publicist Julia Drake told Publishers Weekly Select, a magazine devoted to self-publishing, “and there’s not enough out there about the 99 percent of the authors who’ve self-published a book and it disappears.” The only reality each writer faces is his own.

My first step was to spend $350 to digitize the four books of mine whose rights had been returned to me: Conversations with Capote, The Hustons, Conversations with Michener, Above the Line, and Conversations with Brando. Then I found out about Amazon’s White Glove Program, a program for established writers. If invited in, Amazon will take care of the business of digitizing your books and will work with you to get them ready for self-publication, pending your approval. I was invited to join that program. And then they told me about their Select program, where I would be “allowed” to offer any of my books for free to their readers for up to five days over three months. Why would I do that? I wondered. To raise my profile, I was told. The higher one’s profile, the better chance of gaining new readers. Freebies were designed to create word-of-mouth sales. And since I had more than one book, if a reader took one of my books for free, they might be encouraged to buy the others. Besides the four previously published books, I had seven others I was working on. My Amazon contact thought it would be a smart idea to release them all at the same time. Instead of putting out one book and waiting, I could put out all 11 books, so when someone went to my book page they could see all of them at once. But I was still some distance away from publishing. Before I could digitize them I needed my trusty copy editor to go over each and every paragraph. Once she was done, I needed to place the photos I wanted to include, to get permission to use illustrations and quotes, and to get each book cover designed. Once everything was in order, I gave the books to Amazon. When they said they were ready, I went over each of them and found problems that had to be fixed. That back and forth took a few more months. When it came time to click publish and see these books go public, I next had to think about how to market them. Because so many books go out into the electronic world each day, I was really just getting started. And this was the worst part of the process, because it meant letting all the people I knew, through email, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter, that these books were now available.

This was now my welcome to the real world of social networking. The world where all your friends, and “friends,” and former students send congratulations and encouragement and then go on with their busy lives. In other words, ignoring your pleas to buy your books. That’s when you begin to see the genius in Amazon’s free books idea. If they won’t purchase, then you can give them a taste, select one of the books, and nudge them to buy the others. So, I put up Capote first, and lo and behold, 2,000 people took it the first day. When sales of the other books remained meager, I offered them Brando for free. One thousand took that one. When no one was buying either of the novels, I put one up one month, the other the next. Four hundred people took them. Yoga? No! Shmoga!, my satire on yoga? I could barely give it away. How do I know how many people are buying, borrowing, or taking them for free? Because I can go to my reports on Amazon and check the month-to-date unit sales. Whereas before I had to wait six months to find out how any of my books were selling, now it is instant.

The first month, I earned over $600. The second, around $400. The third, under $200. It’s not exactly what I was selling in print. The Hustons had a 50,000 print run and supposedly sold 80 percent of those; I don’t have the figures of all the other books, but I do know that each of them sold at least in the four or five figures.

Stephen Marche, in Esquire, has pooh-poohed writers who whine about the terrible state of publishing today. He points out that “for writers starting out, there are more options, more means of access to the marketplace, than ever before.” And he quotes two pollsters (Gallup and Pew) who claim that the number of books the average American reads per year is 17. He says we’re in “the golden age for writers and writing.”

I agree that there are more options for writers today, but what Marche neglects to address is how many of these options allow a writer to actually earn a living from his writing. He points to how J.K. Rowling is richer than the queen of England and that Tom Wolfe got $7 million for his last novel, but there will always be writers who hit the literary lottery. It’s all the others in the game that Marche dismisses by saying “Everyone seems to understand and accept this golden age except the writers themselves.” Well, yes, the writers in the trenches. They don’t quite understand and accept. As for the average American reading 17 books a year? You’ve got to be kidding me. I know a lot of educated people. Very few of them read 17 books a year. Most people I know just read occasionally and watch a lot of TV. They can reference Mad Men, Game of Thrones, Seinfeld episodes, and Downton Abbey. But ask them what they thought of The Gravedigger’s Daughter or The Emperor of All Maladies and see if their eyes cross.

“It does seem a bit high,” said Joyce Carol Oates when I asked her what she thought about it. Oates is the only writer I know who can write 17 books a year. “Maybe these are self-help books and cookbooks,” she mulled.

Having taught gifted English majors at UCLA for 10 years, I’m pretty convinced that even they didn’t read much more than what they were assigned. It may be far easier for all of them, and for anyone else, to self-publish these days, but getting people to actually read these things? That’s a whole other story.