Carlos Bulosan’s ‘Freedom from Want’

In 1943, the Post commissioned four writers to craft an essay to accompany each of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, which had quickly come to represent America’s moral imperative during World War II. You can read the other three essays here.

Freedom from Want

Originally published March 6, 1943

If you want to know what we are, look upon the farms or upon the hard pavements of the city. You usually see us working or waiting for work, and you think you know us, but our outward guise is more deceptive than our history.

Our history has many strands of fear and hope, that snarl and converge at several points in time and space. We clear the forest and the mountains of the land. We cross the river and the wind. We harness wild beast and living steel. We celebrate labor, wisdom, peace of the soul.

When our crops are burned or plowed under, we are angry and confused. Sometimes we ask if this is the real America. Sometimes we watch our long shadows and doubt the future. But we have learned to emulate our ideals from these trials. We know there were men who came and stayed to build America. We know they came because there is something in America that they needed, and which needed them.

We march on, though sometimes strange moods fill our children. Our march toward security and peace is the march of freedom — the freedom that we should like to become a living part of. It is the dignity of the individual to live in a society of free men, where the spirit of understanding and belief exist; of understanding that all men are equal; that all men, whatever their color, race, religion or estate, should be given equal opportunity to serve themselves and each other according to their needs and abilities.

But we are not really free unless we use what we produce. So long as the fruit of our labor is denied us, so long will want manifest itself in a world of slaves. It is only when we have plenty to eat — plenty of everything — that we begin to understand what freedom means. To us, freedom is not an intangible thing. When we have enough to eat, then we are healthy enough to enjoy what we eat. Then we have the time and ability to read and think and discuss things. Then we are not merely living but also becoming a creative part of life. It is only then that we become a growing part of democracy.

We do not take democracy for granted. We feel it grow in our working together — many millions of us working toward a common purpose. If it took us several decades of sacrifices to arrive at this faith, it is because it took us that long to know what part of America is ours.

Our faith has been shaken many times, and now it is put to question. Our faith is a living thing, and it can be crippled or chained. It can be killed by denying us enough food or clothing, by blasting away our personalities and keeping us in constant fear. Unless we are properly prepared, the powers of darkness will have good reason to catch us unaware and trample our lives.

The totalitarian nations hate democracy. They hate us because we ask for a definite guaranty of freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and freedom from fear and want. Our challenge to tyranny is the depth of our faith in a democracy worth defending. Although they spread lies about us, the way of life we cherish is not dead. The American Dream is only hidden away, and it will push its way up and grow again.

We have moved down the years steadily toward the practice of democracy. We become animate in the growth of Kansas wheat or in the ring of Mississippi rain. We tremble in the strong winds of the Great Lakes. We cut timbers in Oregon just as the wild flowers blossom in Maine. We are multitudes in Pennsylvania mines, in Alaskan canneries. We are millions from Puget Sound to Florida. In violent factories, crowded tenements, teeming cities. Our numbers increase as the war revolves into years and increases hunger, disease, death, and fear.

But sometimes we wonder if we are really a part of America. We recognize the mainsprings of American democracy in our right to form unions and bargain through them collectively, our opportunity to sell our products at reasonable prices, and the privilege of our children to attend schools where they learn the truth about the world in which they live. We also recognize the forces which have been trying to falsify American history — the forces which drive many Americans to a corner of compromise with those who would distort the ideals of men that died for freedom.

Sometimes we walk across the land looking for something to hold on to. We cannot believe that the resources of this country are exhausted. Even when we see our children suffer humiliations, we cannot believe that America has no more place for us. We realize that what is wrong is not in our system of government, but in the ideals which were blasted away by a materialistic age. We know that we can truly find and identify ourselves with a living tradition if we walk proudly in familiar streets. It is a great honor to walk on the American earth.

If you want to know what we are, look at the men reading books, searching in the dark pages of history for the lost word, the key to the mystery of living peace. We are factory hands, field hands, mill hands, searching, building, and molding structures. We are doctors, scientists, chemists, discovering and eliminating disease, hunger, and antagonism. We are soldiers, Navy men, citizens, guarding the imperishable dream of our fathers to live in freedom. We are the living dream of dead men. We are the living spirit of free men.

Everywhere we are on the march, passing through darkness into a sphere of economic peace. When we have the freedom to think and discuss things without fear, when peace and security are assured, when the futures of our children are ensured — then we have resurrected and cultivated the early beginnings of democracy. And America lives and becomes a growing part of our aspirations again.

We have been marching for the last 150 years. We sacrifice our individual liberties, and sometimes we fail and suffer. Sometimes we divide into separate groups and our methods conflict, though we all aim at one common goal. The significant thing is that we march on without turning back. What we want is peace, not violence. We know that we thrive and prosper only in peace.

We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Under the lynch trees, amidst hysterical mobs. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.

We are the sufferers who suffer for natural love of man for another man, who commemorate the humanities of every man. We are the creators of abundance.

We are the desires of anonymous men. We are the subways of suffering, the well of dignities. We are the living testament of a flowering race.

But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

What do we want? We want complete security and peace. We want to share the promises and fruits of American life. We want to be free from fear and hunger.

If you want to know what we are — we are marching!

Somersaulting into America

The letter that would change my father’s life — and eventually lead to his recent induction into the USA Gymnastics Hall of Fame — arrived in 1964, at his high school in Nara, Japan. Addressed to Yoshi Hayasaki, it was from an American.

My father, 17 at the time, could not make out a single sentence typed by Eric Hughes, a professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. He asked a campus English teacher to translate. “It sounds like he is trying to invite you to come to America,” the teacher told my father.

Hughes, as it turned out, had started a men’s gymnastics team at the University of Washington in 1956, a time when the sport in the U.S. lagged behind Japan and the Soviet Union. While on sabbatical in Japan 1964, Hughes scouted for talent. That was when he first spotted my dad, a 5-foot-3 city and regional champion, ranked as one of the top five gymnasts in Japan.

The letter stated that if my dad earned admittance to the University of Washington, he would be guaranteed a scholarship to the school, and could compete on its team. All my father really knew of America at the time came from watching translated episodes of Rawhide. Coaches and teammates could not understand why my dad would even consider competing in another country — in the U.S. of all places — when Japan was already the gymnastics superpower. Everybody was against the idea, including his father.

Still, the thought of America electrified my dad. He had been offered scholarships to Japanese universities, and saw that many former champions became physical education teachers, while others became foot soldiers for corporations. “I saw my future,” he told me. “It was like a blueprint.”

There is a Japanese proverb: “The nail that sticks out will be hammered down.” It is a saying I’ve thought about throughout my own life, as someone who feels like I’ve at times stuck out, even in America. Here, however, it is possible to find your own way, and embrace the road less taken. Back then, in Japan, my dad could practically see the hammer’s face.

For him, America was uncharted territory that seemed to offer an escape, or at least an adventure. Grudgingly, my grandfather assented, telling Dad: “Do not come back until you have accomplished something.”

To read the entire article from this and other issues, subscribe to The Saturday Evening Post.

How to Be Neutral

Why does America find it so difficult to remain neutral?

Why do we seem impelled to take sides and get involved in global politics?

A century ago, as the U.S. watched Europe sinking in the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson asked Americans to be “neutral in fact, as well as in name. … We must be impartial in thought, as well as action, must put a curb upon our sentiments, as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference.”

But when war returned to Europe 25 years later, President Roosevelt declared, “This Nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well. Even a neutral has a right to take account of facts. Even a neutral cannot be asked to close his mind or his conscience.”

This was not neutrality, wrote Post contributor Demaree Bess, and he knew what he was talking about. For the previous two years he had been living in Switzerland. The small European republic had maintained its freedom for over a century while observing rigorous neutrality, which he defined as “the state of being friendly to two or more belligerents, or at least not taking the part of any.”

The Swiss, he wrote, couldn’t understand how Americans thought they were being neutral when they were encouraging their government “to line up with one set of European powers against another set, even before a war starts.” According to Bess, Americans thought simply declaring neutrality gave them the right “to take sides violently in every conflict which occurs in any part of the globe.”

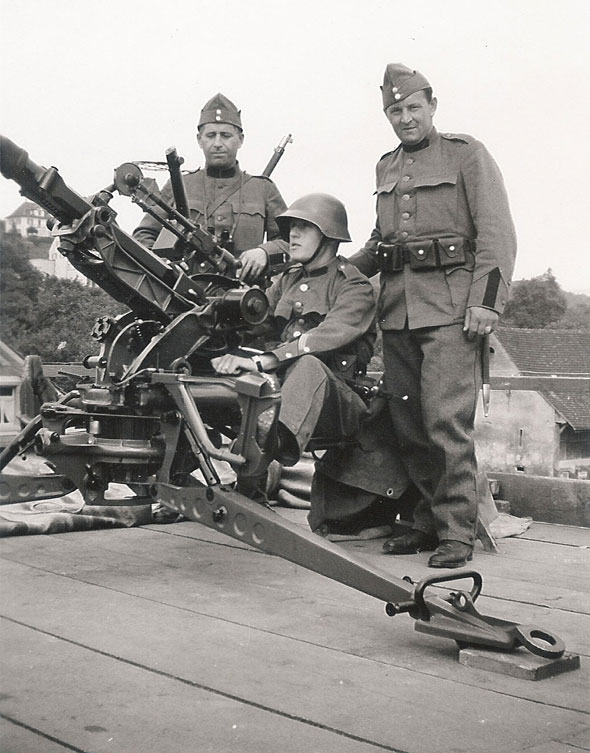

The Swiss would stay out of the war, Bess wrote, because they would not fight for the things they believe in. The only cause for which the Swiss would take up weapons — which they were ready and prepared to do — was an invasion of their homeland. “They never even discuss the possibility of fighting for an abstract principle, such as collective security, or for any distant colony … or an ally in Eastern Europe. … They have only their own little country, which they spend all their time and attention cultivating. They are prepared and willing to fight for that country, if it is invaded.”

Between 1936 and 1939, the Swiss had spent $230 million to reorganize defenses. They modernized weaponry, especially antiaircraft defense and frontier fortifications. The government also increased the amount of training required of all Swiss citizens between 18 and 60 years of age. “This country of 4 million can put an army of 500,000 into the field within two days or less,” Bess wrote. When the Swiss Federal Council saw Europe sliding toward war, it mobilized the entire army. In just three days, its entire national force was ready.

Bess obviously admired the Swiss system, which, he reported, had created a “democracy united in its determination to preserve its democratic ideals as well as to keep its boundaries intact.” Reading his article, you get a sense that he thought the United States would be smart to adopt the Swiss model, and in his words “mind its own business.”

Could the U.S. have remained neutral, as its isolationists wanted? Probably not, in the long run. As much as its citizens might have wanted to stay out of the conflict, the country’s great wealth, spacious land, and open borders would have proved too tempting for the Axis, who would have found some pretext to seize American soil.

Japan was already anticipating an attack on American interests in the Pacific in 1939. Hitler, though, didn’t draw up concrete plans for conquering America, because he believed it was peopled by mongrel races incapable of defending themselves. He probably assumed that, after subjugating Europe and Russia, America’s manufacturing and agricultural wealth would simply fall into his lap.

Switzerland could make neutrality work because of several advantages America didn’t enjoy. First were its formidable mountainous borders. Admirable as its citizen army might have been, its effectiveness depended as much on the country’s alpine geography as its training and spirit. The Swiss army might have proved far less effective if it had to defend a nation as flat as Poland. Nazi Germany had, indeed, drawn up plans to invade Switzerland, but concluded that that conquering such a mountainous country wouldn’t be worth the cost.

Switzerland also benefitted from Nazi’s leniency toward the Swiss whom the Nazis considered essentially German. Hitler and his followers didn’t feel compelled to dominate the Swiss as they had the Czechs and Poles.

Besides, a small, wealthy neutral country next door offered many attractions to Nazi Germany. Switzerland provided an intelligence post where German agents could pick up Allied information. Also, several banks in Switzerland proved very helpful to Nazi officials who wanted to store their plunder beyond the reach of their own government. They found Swiss bankers more than happy to do business with them, even enabling them to store and trade stolen paintings.

Moreover, factories in neutral Switzerland, which weren’t being bombed by the Allies, could provide Germany with a steady supply of much needed steel and weapons. And, for a price, the Germans could use Switzerland’s transalpine railway to keep supplies flowing to their ally Italy.

But Bess couldn’t have known all this in 1939, when neutrality still seemed a workable response to the world war. The next seven months proved what a bad idea this policy was. One by one, other neutrals — Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Holland — were seized by the Nazis, bringing the war closer to the shores of neutral America.

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago: