Technology Was Killing Attention Spans 115 Years Ago

People are too easily distracted. News of a major tragedy will hold their interest for a few days, but boredom quickly sets in and attention drifts away.

That’s what the Post editors concluded after people learned a hurricane had destroyed a major American city on the Gulf Coast. “Money and food were sent,” they wrote. “The heart of the country went out in sympathy. The awful story was eagerly read. But by the third day there was a distinct falling off in interest. … By the [fifth day] even the headlines were not looked at.”

They weren’t describing New Orleans in 2005, but Galveston in 1900.

In September of that year, a hurricane swept inland to destroy a city and kill some 10,000 people, making it still the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history. It was, of course, a major news story. Yet two months later, Post editors observed that people had quickly lost interest in the tragedy.

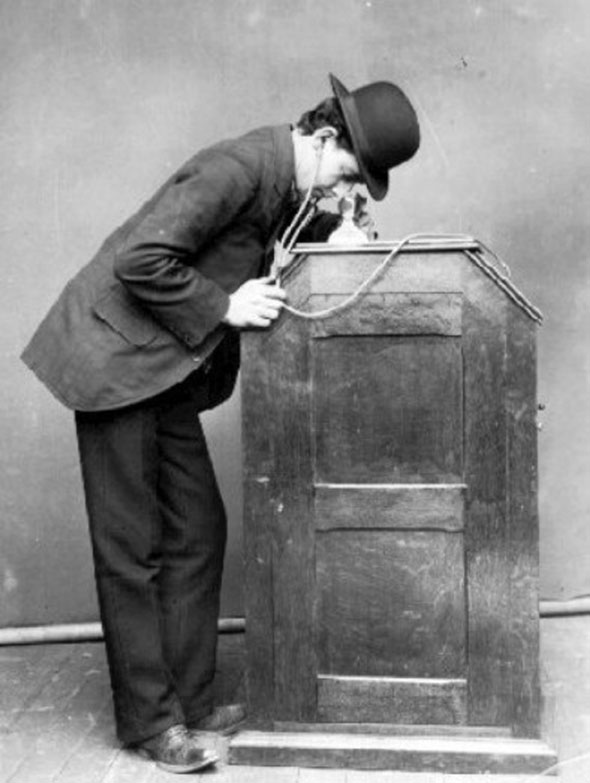

The editorial — published nearly a century before life became enmeshed with the Web and smartphones — blamed technology for the lack of focus. Life was becoming too fast-paced. Rapid communication, made possible by steamships, the telegraph, and the new telephone, was making people impatient with any delay. Even the kinetoscope, Edison’s patented personal hand-cranked movie viewer (pictured above), was contributing to America’s growing inability to stay focused.

We can smile at the thought that steamships were making people more distracted. But it appears that technology does indeed make it harder for us to concentrate. This year, the Microsoft Corporation published a study that showed between the year 2000 and 2013 the average attention span dropped from 12 to 8 seconds. That’s one second less than the attention span of a goldfish.

If true, this fact suggests that people will find it increasingly difficult to remember and learn from tragedy. And if that’s the case, maybe we should heed the editors’ advice from 115 years ago: “But it were well if, with all our increasing swiftness, we should stop and think a while now and then.”

50 Years Ago: Racial Violence Explodes in Birmingham

1964 © SEPS

On March 2, 1963, the Post ran an article on racial tension in Birmingham, Alabama, entitled “A City In Fear.” The editors couldn’t know how prophetic it was.

The story appeared as part of a series focusing on the progress of civil rights in the South. Post articles reported Georgia and South Carolina were taking early steps toward integration, but Alabama was stubbornly resisting any change.

The nation had already heard of Freedom Riders—activists traveling through the South to help register black voters—being viciously attacked in Birmingham. And newspapers had carried shocking photos of Birmingham police using fire hoses and police dogs to break up demonstrations by black activists.

In his report from Alabama, journalist Joe David Brown said he was discouraged by the racial violence he found in his old hometown of Birmingham. “The people were as charming as ever, but their hardened attitude, their fear of desegregation saddened me.”

Birmingham, he wrote, was the largest American city that was taking no steps to address its racial problems. The city refused to establish any official communication between its white and black communities. “If [the city] had hired experts and set out to do it deliberately, it probably could not have been so successful in creating a bad national reputation,” Brown wrote.

Politicians were capitalizing on fears in the white community by talking up resistance to integration. The president of the city commission had recently closed the city’s entire park system because a federal court had ordered the city to integrate its facilities.

The forces of segregation had been encouraged by the recent election of George Wallace to the governor’s office. He had gathered support by preaching unyielding resistance to federal orders to integrate the state’s schools, claiming that he would go to prison before allowing black students to enter in the state’s university. In his inaugural address, he made a characteristic appeal to the pride and fear of the state’s segregationists. “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

All this demagoguery had set back the cause of civil rights, as a prominent Birmingham minister told Brown, “For more than eight years the mightiest and most influential people in this town have told us to fight, to resist, not to give in at any cost. … After whipping these people into a fighting mood … it simply is not possible to tell them that the rules have been changed.”

The absence of progressive leadership further encouraged a small number of racists who had begun a campaign of terror in the community. Just three months earlier, “a crude dynamite bomb ripped apart the front of a church in which a group of small Negro children were rehearsing a Nativity play. It was the 17th bombing in and around Birmingham since 1957, all of them directed against Negro churches and the homes of civil-rights leaders.”

The segregationists of Birmingham had long maintained control by suppressing any opposition from the black community. Now they were beginning to smother opposition among Birmingham’s white residents. Their threats prompted newspapermen to keep loaded shotguns by their front doors. They silenced business leaders by threatening attacks on their spouses. They dumped garbage on the property of citizens who endorsed integration or, in some cases, burned crosses on their lawns. In the previous five years, more than 50 crosses had been burned in the city.

Despite these threats and legal actions from the city, integration still proceeded. On September 10, 1963, classes were held in Birmingham’s first integrated classrooms.

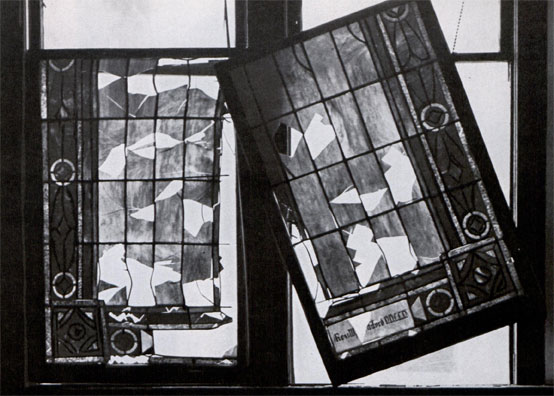

The following Sunday, at 10:22 a.m., a bomb exploded under the stairway of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church. Four young black girls within the church were killed, and 22 people were injured by flying rubble.

In his 1964 article on the “The Birmingham Church Bomber,” author George McMillan wrote, “As nothing else had done—or perhaps could do—it epitomized the ugliness of racial conflict.”

Immediately after the bombing, the FBI entered the case, announcing it was launching “the biggest manhunt since the Dillinger case.” But the big manhunt was interrupted a few weeks later when the Alabama State Police arrested three men for the bombing: Robert Chambliss, Charles Cagle, and John W. Hall. State prosecutors were only able to charge the men with illegal possession of dynamite. Convicted, the men were fined $100 and sentenced to 180 days in jail. They appealed and, at the time of the article, were free on bail.

The FBI later admitted that the state police had made their arrests before federal investigators could gather the evidence necessary to convict the men for murder.

Two years after the bombing, the FBI focused on Chambliss and two associates: Thomas E. Blanton Jr. and Bobby Frank Cherry. But the FBI’s surveillance evidence was inadmissible in court, and witnesses refused to testify against any of the suspects.

It would be 14 years before Chambliss was indicted for the murder of the girls. He was eventually convicted of one murder and died while serving a life sentence. Blanton avoided punishment for 38 years before he was finally convicted in 2001 and sentenced to life in prison. The next year, Cherry was convicted and died in prison two years later.

The church bombing, and the shooting of two other children that day, represents the worst of racial violence in the city. But the violence shown by Birmingham’s police, and anonymous bombers, introduced a new level of bitterness to the national campaign for civil rights.