Considering History: Pudge Heffelfinger — The First Ever Pro Football Player

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As the nation and world build up to the Super Bowl, always one of the most watched events of the year, it’s difficult to imagine a time when professional football wasn’t near the center of our cultural and social landscape. But the sport evolved through a series of distinct late 19th and early 20th century stages. But it was the career of one particularly prominent early football star named Pudge Heffelfinger that opened the door to pro football.

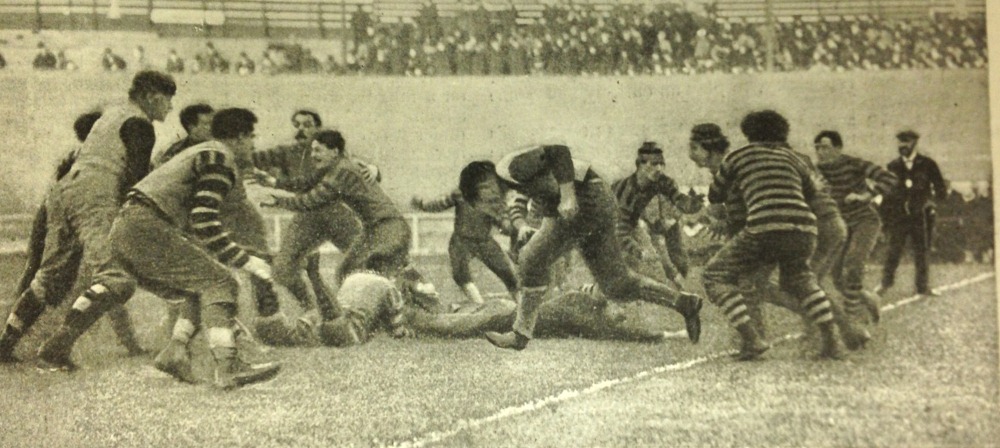

Invented sometime in the mid-19th century (as with baseball, the sport’s origins are hazy and contested) and played intercollegiately for the first time in 1869, by the 1880s football occupied a significant place in the national sporting scene. But the two central realities of football in the late 19th century are equally hard to believe today: that college football was pretty much the only game in town, and that at the center of the college football universe was the Ivy League, schools like Harvard and Yale.

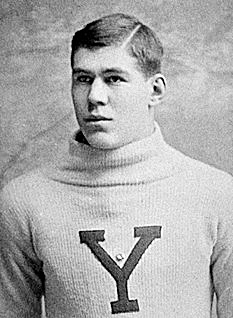

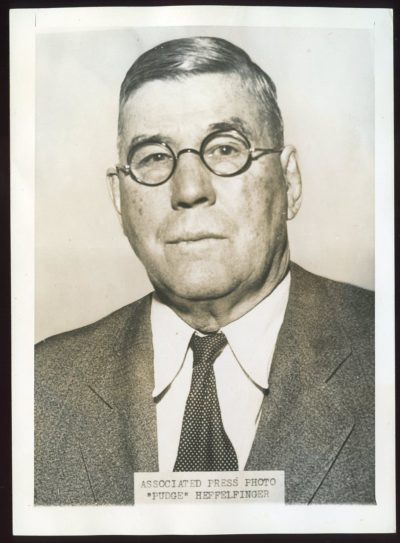

William “Pudge” Heffelfinger was born in Minneapolis in 1867, his father a Civil War veteran who had come by riverboat to the frontier city and opened a shoe factory there. A star athlete in high school, Heffelfinger went on to become a three-time All-American defensive guard during his four years at Yale (the 1888 to 1891 seasons).

Heffelfinger allegedly got off to a slow start – he was not aggressive enough, despite his 6’3” 210-pound frame. In order to motivate him, one of the assistant coaches wrote him a rousing letter in blood.

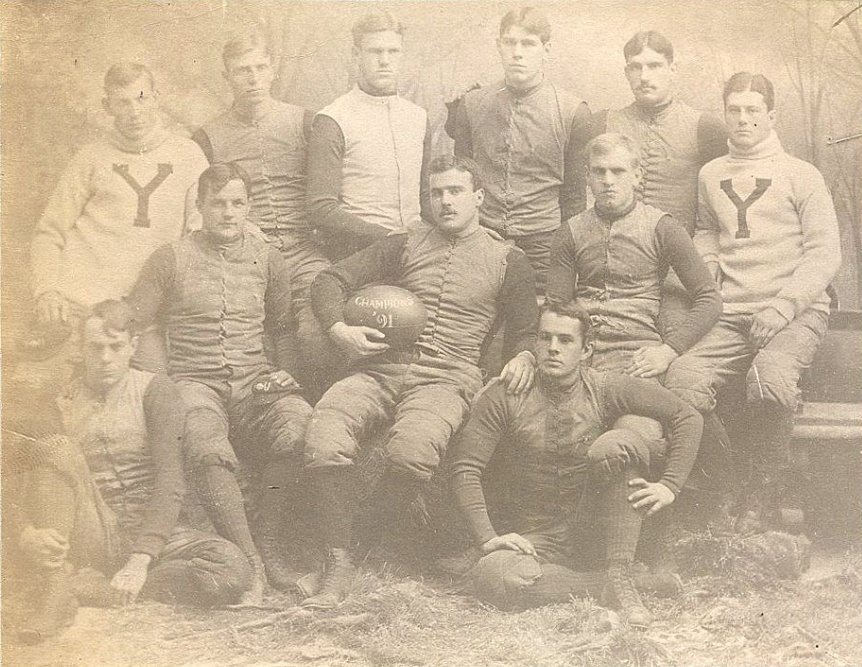

But it was under legendary coach Walter Camp, that Heffelfinger led the Yale team to undefeated seasons. The 1888 team, moreover, also gave up precisely no points on the season, outscoring its thirteen opponents 698 to 0 (for an average victory of 53.7 to 0). Few if any sports teams, from any era and at any level, have equaled the success of that Ivy League football squad.

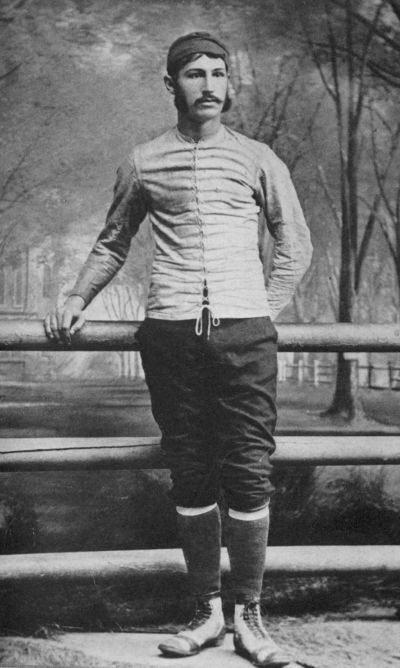

Professional sports were beginning to emerge in America during that same late 19th century period; but when compared with the juggernauts that our major sports teams and leagues now are, they developed in a strikingly haphazard fashion. Both the historic paycheck that made Pudge Heffelfinger the first professional football player and the story of how that document was discovered embody that randomness.

In the 1960s, the Pro Football Hall of Fame, alerted by a rediscovered item from Pittsburgh newspapers, recovered a long-lost page from the account ledger of the Allegheny Athletic Association. That Association was one of many semi-pro organizations in the era through which former college stars like Heffelfinger could continue to play the game while pursuing their professional careers in other areas. But in late 1892, all that changed: the rediscovered ledger page reveals that Heffelfinger was paid both a $25 salary and a $500 “game performance bonus” by Allegheny to play in a game against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club on November 12, 1892.

It appears from the ledger and other sources that Heffelfinger was the only player paid to appear in that game, making him the first professional football player. Over the next few years, six other prominent players would be paid, some for individual games and some on salary for entire seasons. One of them was only 18 years old: John Brallier, who while quarterback at Pennsylvania’s Indiana College was paid $10 by the Latrobe semi-pro team for a September 1895 game against rival Jeannette. Such was the haphazard nature of “professional” sports in the 1890s, and yet these were the vital first steps toward the cultural behemoth that is the 21st century National Football League.

By the mid-20th century, both football in general and professional football in particular had become far more organized and wide-ranging. In his final role in football (after a few years of coaching at various universities and an unsuccessful attempt to take up the family shoe manufacturing business) Heffelfinger compiled and authored Heffelfinger’s Football Facts, an annual publication that featured statistics and schedules for both college and pro teams. This periodical, which was published between 1935 and 1950, was one of the first of the now-ubiquitous annuals created for every major sport. Heffelfinger’s Football Facts did more than just reflect football’s growth and popularity, though—it also helped contribute to those trends, using the name and identity of this iconic early star, as well as new 20th century journalism and media technologies, to publicize and sell the sport to familiar and new audiences alike.

In recent years, controversies such as concussion concerns and social protests have shifted the football landscape, and will no doubt continue to. But as Pudge Heffelfinger reveals, the story of football has been an evolving one from the outset.

Let’s Make Football a College Major

On a fall day in 2012, right after taking a frustrating sociology exam for which he would receive a B, Cardale Jones – a student-athlete at Ohio State University – tweeted something that he would later regret:

Jones saw college as football and classes as an inconvenience. At the time, and again two years later when the quarterback led his team to a national championship, Jones’s tweet brought intense criticism. But maybe it shouldn’t have.

College football players spend more than 40 hours per week on football, including time on the practice field, in the weight room, with trainers, and in film study and team meetings. On average, college athletes spend more than 30 hours a week on their sport. The US National Collegiate Athletic Association has a rule limiting college athletes to 20 hours per week, but it is rife with loopholes and a target of lawsuits.

Such ambitious schedules leave college athletes exhausted and with little energy for coursework. In many cases, the primary reason they are attending college in the first place is to play a sport. Many athletes evince a dedication exceeding all but the most committed students of the sciences or humanities.

In fact, the phrase ‘student athlete’ is redundant. To be an athlete is to be the student of a discipline as rigorous and as noble as literature, chemistry or philosophy. The ancient Greeks, who invented the idea and practice of the academy, conceived of athletics as a basic component of education and culture (paideia).

Ancient precedents aside, any college course catalogue today reveals many majors focused primarily on a physical or practical, rather than theoretical, field of study. The University of California, Berkeley, my alma mater, supports majors in art practice, dance and performance studies, theatre and performance studies, music, film, creative writing, journalism, communications, and business administration. The art practice major consists ‘largely of studio courses’ and focuses on artistic production, although students also take classes in art history, theory and business. All of these majors combine educational requirements of practice and theory, but focus on practice. They provide an obvious model for majors in sport.

The football major, for example, would consist of the practicum, the many hours of physical training, practice, film study and meetings. Courses would also be required in the history, science, criticism and business of the discipline, as well as in the related fields of physiology, nutrition, journalism and sports management. Indeed, all of these fields of study already exist. A graduate of the football major could claim some expertise in the field, and be someone with the potential for significant impact, as an athlete, coach, trainer, agent, commentator, consultant, or team member in a complex organisation.

Some critics might argue that sport is not intellectual enough to be enshrined as a field of academic study. But this objection presumes a much too restricted view of intellect, a proper account of which must also clearly make room for performative activities such as art, theatre and dance. Thanks to recent scientific and academic research, we have a much better appreciation of the intelligence required for athletic excellence.

Sport intelligence requires cognitive performance that is extremely demanding: the ability to read the complexity of a situation, to come to near-instantaneous intuitive judgments about how to react, and to move the body accordingly. It requires, as the journalist Chuck Squatriglia explained about soccer research in Wired, ‘what neuropsychologists call executive functions, which include the ability to be immediately creative, see new solutions and quickly change tactics’.

In this respect, the demands of football are especially rigorous. Because it involves large teams with 22 players lining up on any one play to perform a strategic manoeuver, if on offence, or to counter that manoeuver, if on defence, it requires more preparation off the field than any other sport. American football players spend more time in meeting rooms, watching film and reading binders of plays than doing anything else. As Nicholas Dawidoff wrote in The New Yorker:

In developing a game plan, coaches typically break down everything that happened in the opponent’s past four games to granular levels of ‘tendencies’ – down, distance (to a first down), field position, and time remaining on the game clock. Once assembled, this research fills many pages of the game-plan binders players are given on Wednesday to prepare them for Sunday. (Teams have also begun to use iPads.) The binders are dense with intricate drawings and written instructions. They are often as thick as a left tackle’s fist.

What players learn is then tested under high-stress real-world conditions, in practice and actual games. How many fields of study can say the same?

I would also argue that people suffer from an impoverished view of the human mind. The popular tendency is to think of consciousness as something that happens inside the head or the brain, but philosophers are challenging this view with an approach that sees the mind as the interaction of one’s entire neurological system with the environment. The US philosopher Alva Noë, for example, who has written several books exploring a new theory of mind, appeals to practices such as dance, which demonstrate how mental activities can be bodily and spatio-temporally extended, coordinated and social, and both reactive to and manipulative of other people and the world. And psychologists such as Howard Gardner have theorised that kinaesthetic intelligence, the ability to use the body to solve problems, is a distinct form of intelligence worth study.

While these distinctions might be unfamiliar to many, people do seem to recognise the unique intelligence of athletes and how that intelligence can translate into other domains. Businesses, law firms and other complex organisations requiring a sophisticated balance of competition and cooperation often recruit from college athletics, especially from team sports.

Creating sports majors also addresses real problems. Unlike philosophy or anthropology, sport is a booming multi-billion dollar industry in the United States and around the world. It offers potential for employment in an extensive variety of fields: coaching (high school, college, pro), physical training, marketing, law, consulting, design, management, and more. Sports majors would help athletes to succeed in these fields. If Cardale Jones, for example, does not make it in the National Football League, his next-best options might be as a football coach, trainer, agent or businessman.

For at least a century, US universities have decided to include athletics in higher education, and that is not going to change. Nor should it. We just haven’t pursued the logic to its proper end. It is time to make football a major.![]()

David V Johnson

This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.