Cartoons: Pigskin Grins

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Lamb

November 27, 1954

Harry Mace

November 15, 1952

November 1, 1980

Al Johns

October 26, 1957

Zeis

October 25, 1958

Walter Wetterberg

October 25, 1952

Gallagher

October 16, 1954

Bernhardt

September 25, 1954

Roy Wilson

September 18, 1954

Ernie Garza

December 9, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

5 Things You Didn’t Know About Monday Night Football

Monday Night Football kicked off 50 years ago this week. The broadcast was a crucial component in establishing the NFL as a dominant ratings force and making it the most-watched sporting league in the United States. Prior to its move to ESPN in 2005, MNF was one of the longest-running prime-time shows in the history of network TV. With a new season underway, here are five things you didn’t know about Monday Night Football.

1. It Has Hosted More Than 700 Games

Throughout the 50 seasons of Monday Night Football, the series has played 718 games as of September 21, 2020. The very first game saw the Cleveland Browns host the New York Jets. The Browns won 31-21 in a game that was watched by 33 percent of the total American viewing audience for that evening.

2. Gifford Had the Chair Longer Than Anyone

Howard Cosell remains the most famous original commentator; he held his spot for 13 years. Frank Gifford joined in the second season, and his run lasted until 1998, making him the commentator who was with the show the longest with a total of 27 years. There have been about 40 play-by-play announcers and color commentators across the history of the program on ABC and ESPN; the current team consists of Steve Levy, Brian Griese, and Louis Riddick. There have been dozens of sideline reporters and more than a dozen radio commentators; the current radio team is Jim Gray, Kevin Harlan, and Kurt Warner.

3. Famous Guests Have Hit the Booth

Over the years, a number of celebrities dropped by the broadcast booth. Visitors have included Kermit the Frog, Richard Nixon’s first vice-president Spiro Agnew, and President Bill Clinton. On December 9, 1974, both John Lennon and Ronald Reagan were in the both at the same time. Sadly, just six years later on December 8, 1980, Lennon was shot and killed in New York City. Cosell broke the news to most of America near the end of a Monday Night game between the New England Patriots and Miami Dolphins.

4. It Took Over American Sports and Went Global

MNF was firmly entrenched in the Top Ten of the weekly broadcast ratings for years, becoming one of the most popular shows in America. It elevated football to the position of the most-watched sport of the big three in the States, dethroning Major League Baseball as the favorite and holding off NBA basketball even at its biggest. The show is carried in Europe, Australia, and South America. ESPN has American broadcast rights, including streaming, through 2021. As of August, ESPN is looking to improve the deal for an extension.

5. Monday Night by the Numbers

The most-watched game ever was the Miami Dolphins versus the Chicago Bears on December 2, 1985. The Dolphins ruined the Bears’ shot at a perfect season, handing them their only regular season loss; the Bears would go on to win the Super Bowl (while, one presumes, doing the “Super Bowl Shuffle”). The Dolphins, however, take the title of Most MNF appearances (their 85th appearance is this season). The highest scoring game ever was in 1983 when the Green Bay Packers and the now-titled Washington Football Team ran up a combined 95 points.

The full “Monday Night Miracle” game (Uploaded to YouTube by the NFL)

MNF has been the stage for some amazing comebacks. One of the most popular came in 2003 when the Indianapolis Colts were down 35-14 against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Colts quarterback Peyton Manning engineered a comeback with four minutes left on the clock to tie the game; Colts kicker Mike Vanderjagt kicked a winning field goal in OT, giving the Colts a 38-35 win. However, only one game is called the “Monday Night Miracle,” and that honor goes to the October 23, 2000, game between the Jets and the Dolphins. The Jets scored a seemingly impossible 30 points in the fourth quarter, tying the game and sending into OT; when it was all over, the Jets had squeaked by 40-37.

Featured image: pixfly / Shutterstock

Considering History: The Washington Redskins, Oklahoma Territory, and the Myth of the “Vanishing Indian”

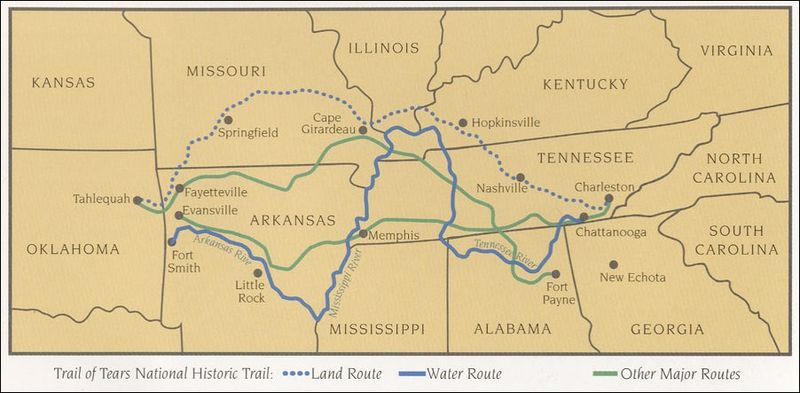

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Recently, we have seen two striking decisions on longstanding issues connected to Native American communities. On July 9, in one of its last announced decisions of this session, the Supreme Court ruled that the eastern half of the state of Oklahoma remains “Indian territory” under 19th century treaties that guaranteed the land for tribes forced west on the Trail of Tears, treaties that have never been amended by Congress and so (the Court ruled) continue to hold today. And on July 13, the NFL franchise the Washington Redskins formally announced that the team will be changing its nearly century-old racist name and logo.

The details of these two decisions are quite specific to their respective arenas, and reflect evolving conversations in each case. But taken together, they exemplify two longstanding and contrasting national narratives: those which depict Native Americans through reductive, stereotypical images in order to justify attempts to expel and destroy native communities; and those which recognize instead Native Americans’ foundational and continued presence within America.

In order to justify his proposed, genocidal Indian Removal policy which produced the Trail of Tears, President Andrew Jackson depicted Native Americans through such stereotypical and racist imagery, defining them as savages unable to coexist with European-American communities or indeed exist at all within the expanding Early Republic United States. In his December 1829 first President’s Annual Message to Congress, Jackson argued that “this fate [disappearance] surely awaits them if they remain within the limits of the States.” And in his December 1833 fifth annual message, Jackson went much further, claiming, “That those tribes cannot exist surrounded by our settlements and in continual contact with our citizens is certain…Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.”

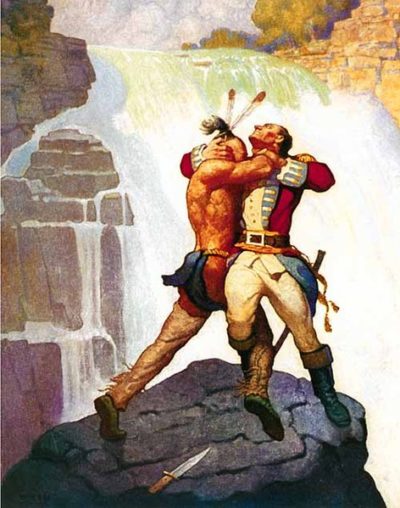

Jackson’s more aggressively racist depictions of Native Americans were complemented by a gentler and more insidious exclusionary perspective that came to be known as the “Vanishing Indian” narrative. Often advanced by figures and communities sympathetic to native rights, this narrative relied on images like the admirable but doomed “Noble Savage” to depict Native Americans as tragically but inevitably disappearing from the continent. James Fenimore Cooper’s bestselling historical novel The Last of the Mohicans (1826) illustrates this trope, arguing from its title on that its heroic Native-American characters are the “last” of a tribe that in fact still existed in Cooper’s era (and still does in our own). Poet Lydia Huntley Sigourney’s “Indian Names” (1834) is even more striking, as Sigourney uses the persistence of Native-American names on the American landscape to angrily (and inaccurately) lament the destruction of native communities: “Ye say they all have passed away,/That noble race and brave/… But their name is on your waters,/Ye may not wash it out.”

The “Vanishing Indian” narrative became a dominant trope across the 19th century and into the 20th, and in subtle but significant ways informed numerous prominent cultural works, as illustrated by Wellesley Professor Katharine Lee Bates’s 1893 poem “America” that became the lyrics for the song “America the Beautiful” (1910). That trope is most apparent in Bates’s second verse, where she describes America’s origin point: “O beautiful for pilgrim feet/Whose stern, impassioned stress/A thoroughfare for freedom beat/Across the wilderness!” But Bates likewise disappears Native Americans from the idealized images of the national landscape with which her poem opens, and which were inspired by a cross-country train trip from her Massachusetts home to a summer teaching job in Colorado. Bates originally named her poem “Pike’s Peak,” as she wrote it after a day trip ascending the mountain — but, like that name itself, her poem leaves no place for the Ute and Arapaho tribes who had been part of that landscape long before explorer Zebulon Pike arrived.

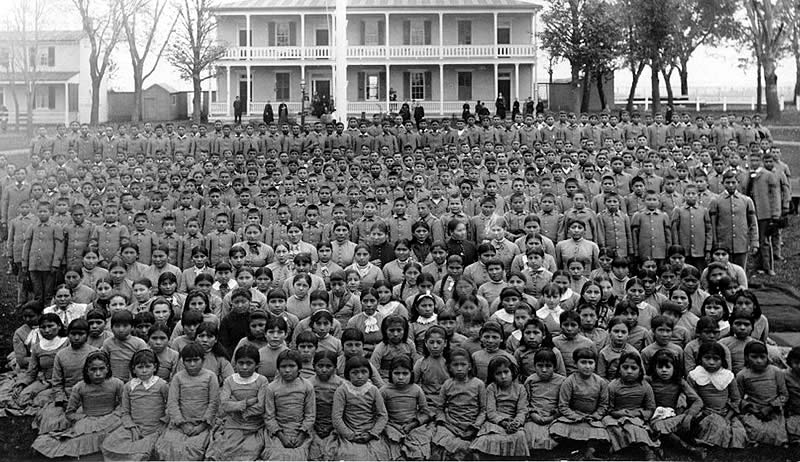

Bates’s 1893 trip took place just two-and-a-half years after the December 1890 Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota, an exemplification of the far more violent exclusionary attacks upon Native-American communities that continued throughout the 19th century. The late 19th and early 20th century also featured another, even more insidious form of cultural genocide designed to facilitate the disappearance of Native-American cultures: the boarding school movement, which (as Carlisle Indian Industrial School founder and former “Indian Wars” Captain Richard Pratt put it) was intended to “kill the Indian, and save the man.” Both these military and educational efforts illustrate that the “Vanishing Indian” was not just a cultural image, but also and most importantly an ongoing white supremacist goal.

As I wrote in this October 2018 Considering History column, Native-American activists and communities have consistently used legal and political means to challenge such attacks and advocate for their survival and their rights. In response to Jackson’s Indian Removal policy the Cherokee nation did so forcefully, with the tribe’s leaders drafting a series of “Cherokee Memorials” to the U.S. Congress that were published in the tribe’s newspaper The Cherokee Phoenix and submitted to Congress to request their assistance. The Cherokee also took their claims to the court system, and the Supreme Court sided with their rights to their land in the Worcester v. Georgia (1832) decision. Jackson famously ignored the Court and proceeded with removal.

Native-American legal and political efforts continued for the next century-and-a-half, including the two prominent moments I highlighted in my earlier column: Ponca Chief Standing Bear’s legal challenge which resulted in the groundbreaking 1879 decision that “an Indian is a person” for purposes of the law (and otherwise); and the numerous activists, including Zitkala-Ša and Nipo Strongheart, whose advocacy led to the watershed 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

The 1960s and 1970s American Indian Movement, founded in Minneapolis in 1968, continued to utilize the political and legal system to advocate for native lives and rights, while fostering the Red Power and Native-American Renaissance cultural movements of late 20th century America.

These destructive myths and their effects have endured, as illustrated by the horrifically high numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths on Native-American reservations — one more way (among too many, including the kidnappings and murders of native women and the destruction of native lands for pipeline construction) in which native communities continue to face the threat of disappearance. But the Supreme Court decision embodies a perspective in which Native-American rights and presence are seen and supported, and where native communities are defined as foundational and integral parts of America’s history, identity, and future.

Featured image: The delegation of Sioux chiefs to ratify the sale of lands in South Dakota to the U.S. government, December1889 / photo by C.M. Bell, Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)

Contrariwise: Youth Football Should Be Sacked

The numbers don’t lie. When it comes to sports in America, nothing’s bigger than football. More people watch it than any other sport, and the NFL’s marquee event, the Super Bowl, is viewed by roughly one-third of the country annually. But the sport’s wild popularity provides cover for a number of problems, not the least of which is the staggering number of injuries players at all levels suffer. And that’s why we need to end youth football in America.

According to the National SAFE KIDS Campaign and the American Academy of Pediatrics, every year, more than 775,000 kids under age 14 are treated in E.R.s for sports injuries. Nearly 215,000 of those come from youth football, with 10,000 kids requiring extra hospitalization. Though many consider hockey one of the most violent of team sports, for every reported injury from youth hockey, there are ten from football.

Those statistics alone are disconcerting, but also consider the impact of concussions or, worse, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). That debilitating condition, caused by repetitive blows to the head, has been shown to contribute to a wide range of maladies, from depression and anxiety to insomnia and memory loss. In the worst cases, it’s a factor in behavioral issues, progressive dementia, and even suicide. And it isn’t confined to NFL athletes. According to a 2012 piece in the Journal of School Health, every year, youth football players between the ages of 5 and 18 suffer 23,000 nonfatal traumatic brain injuries. The cumulative effect of these injuries doesn’t begin at the advanced levels; it begins anytime a child laces up and takes a blow to the head, no matter their age.

For every reported injury from youth hockey, there are ten from football.

If you’re wondering how youth football continues to exist with all these possible outcomes (not to mention the potential for paralysis, broken bones, and internal injuries), then you’re asking the right question.

Sure, removing youth football from middle schools and junior highs would dismantle the feeder system that leads to high school, college, and the pros. To that I say, “So what?” The long-term health of America’s kids is more important.

This article is featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Super Bowl Bests

The Big Game will be played today for the 54th time. Just in time for the impending clash between the Chiefs and the 49ers, here’s a look at some Super Bowl superlatives, from the best movie trailer debut to the best half-time show and more.

Best Movie Trailer: The Avengers (2012)

The Avengers Super Bowl trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Marvel Entertainment)

It’s easy to forget now in the age of Marvel movie domination, but the first Avengers film was considered a risky premise built on a gamble. In the early 2000s, the non-X-Men and Spidey characters were considered the B List. But that all changed with the 2008 breakthrough of Iron Man, the first part of Marvel Studios honcho Kevin Feige’s master plan. The next four movies (Incredible Hulk, Iron Man 2, Thor, Captain America: The First Avenger) built toward the formation of the team. A teaser at the end of Captain America (“Some Assembly Required”) and another teaser (set to “We’re in This Together” by Nine Inch Nails) set the stage, but the Big Game Trailer included the first version of the now-iconic “circle shot” of the team together for the first time. The Avengers had assembled, and an unprecedented string of successes would follow.

Best Commercial: Apple, “1984” (1984)

How Apple’s “1984” Commercial Changed the Super Bowl Forever | NFL Films Presents (Uploaded to YouTube by NFL Films)

There will always be endless debate about the best ad. There have been long-lasting favorites from the likes of Volkswagen (“Vader Kid”), McDonald’s (Jordan vs. Bird, “nothing but net”), Pepsi (1992 Cindy Crawford), and countless memorable beer spots. But potentially the craziest one is the Apple ad that ran only once. Evoking the films of Fritz Lang and the writings of George Orwell, the spot suggests liberation from a gray-hued dystopian by … the Macintosh computer? Though the spot aired just one time, it consumed conversation with opinion pieces, TV news airtime, and talk show discussions. Publications like Business Insider consider this the moment that Super Bowl ads became the biggest commercial availability of the year.

Best Half-Time Show: Prince (2007)

Prince Performs “Purple Rain” During Downpour | Super Bowl XLI Halftime Show |NFL (Uploaded to YouTube by the NFL)

You know a half-time show transcends mere mid-game entertainment when the NFL makes a mini-documentary about it. In the midst of pouring rain, the crowd heard an opening take on Queen’s “We Will Rock You.” Then the stage lit up: it was The Symbol. Prince appeared, said, “Dearly beloved … ” and the crowd went bonkers. What followed was a super-charged performance that included a mosaic of tunes like “Let’s Go Crazy,” “1999,” “Baby I’m a Star,” CCR/Tina Turner’s “Proud Mary,” Dylan/Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower,” Foo Fighters’ “Best of You,” and, of course, “Purple Rain.” It was showmanship of the highest level, made more incredible by the artist’s ability to transcend, and in a way, even take control of the weather to enhance the performance.

Best Play (tie): The Riggins Run and the Tyree “Helmet Catch”

Ask 50 people what the Best Super Bowl Play Ever was, and you’ll probably get more than 50 answers. However, if you ask people to list some of the best plays, a few elite moments will rise to the top every time. For that reason, the Post offers two selections, appropriately split between a run play and a pass play.

In Super Bowl XVII in 1982, the Redskins squared off against the Dolphins. Trailing on a 4th and 1, the Redskins handed the ball to John Riggins. Riggins broke through to pick up the 1st down … and just kept going. He ran for an additional 41 yards, right into the end zone. The play turned the tide of the game, and Riggins was named Super Bowl MVP.

In 2008’s Super Bowl XLII, the Giants were running out of time against the Patriots. In the final two minutes, scrambling Giants QB Eli Manning threw to wide receiver David Tyree, who was facing his own heavy pressure. Remarkably, Tyree secured the ball in mid-air by holding it against his helmet. The play gained the Giants 32 yards and a 1st down. The Giants went on to win, 17-14.

Best Game: Super Bowl LI (2017)

Super Bowl LI highlights. (Uploaded to YouTube by the NFL)

Let’s face it. Some Super Bowls have been thrilling, and others have been one-sided affairs that were decided in the early going. This was a spirited nail-biter that went into the first OT in Super Bowl history. You had the New England Patriots with Brady and Belichick and the Atlanta Falcons had MVP QB Matt Ryan. It certainly looked like it could be a blowout, as the Falcons led 28-3 in the third. But the Patriots came roaring back, dropping 25 on the Falcons to take it into OT. The Patriots won the coin toss and converted that stroke of luck into a TD, wrapping up their fifth championship.

Featured image: LunaseeStudios / Shutterstock

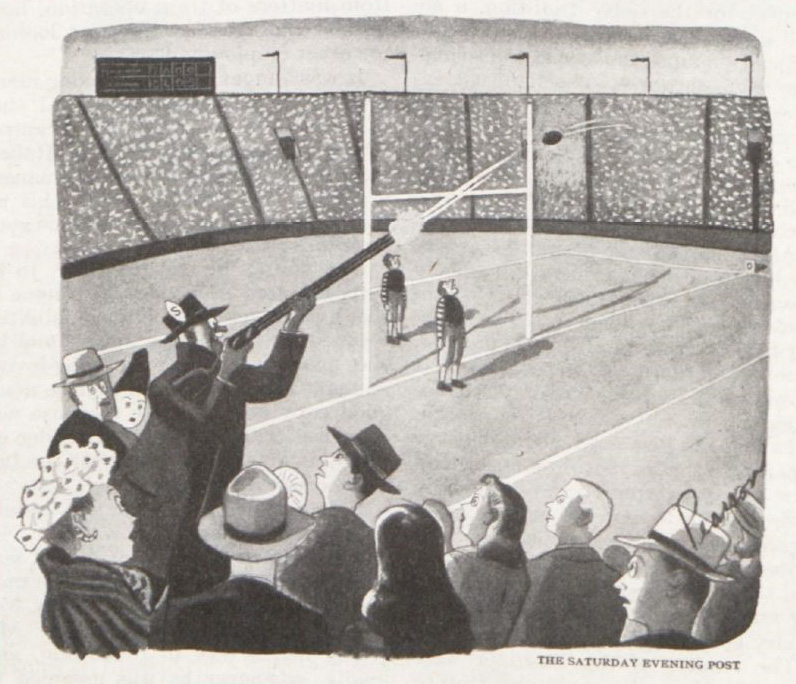

Cartoons: Gridiron Grins

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Blakley

November 18, 1950

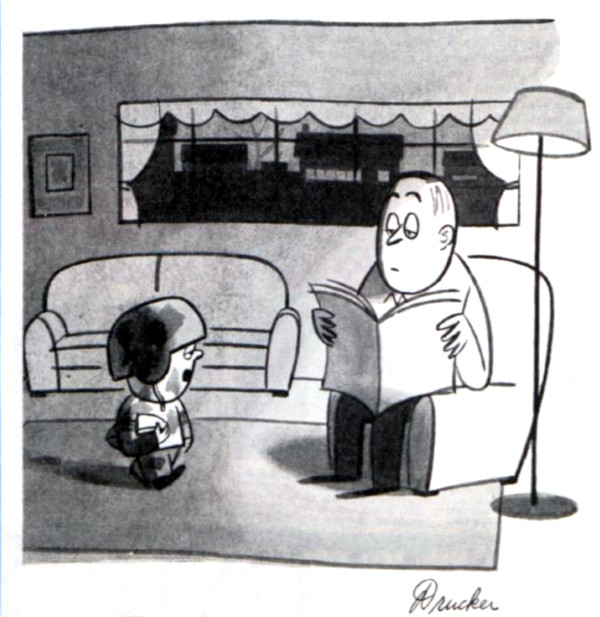

Drucker

November 17, 1951

Drucker

November 17, 1951

Starke

October 6, 1951

John M. Price

October 6, 1951

Tom Henderson

September 30, 1950

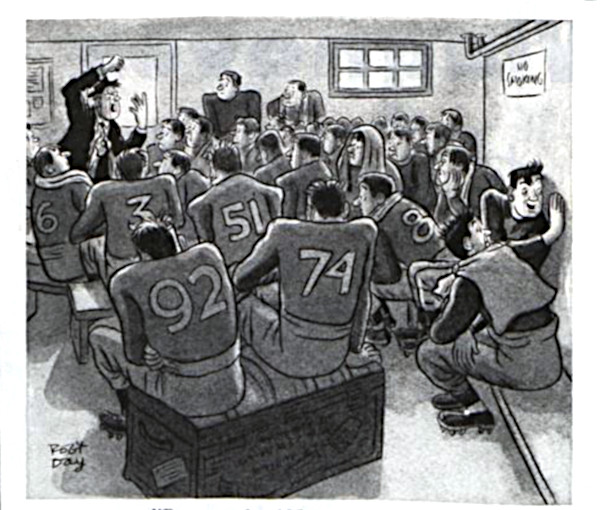

Robt Day

November 25, 1950

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The 7 Most Controversial Sports Moves

More than sixty years ago, the Dodgers made a move that’s still hotly debated. It wasn’t about management or personnel; it was about the location of the team itself. Forsaking Brooklyn for Los Angeles, the Dodgers earned New York’s eternal enmity in 1957 (and were followed by another New York team, the Giants, the following year). Team moves happen for a number of reasons (mostly money), but some have a harsher effect on the locals than others. Here are seven of the most controversial team moves in sports.

1. 1945: What Do You Mean the Rams Are from Cleveland?

The Rams franchise was established in Cleveland in 1936; initially, they were part of the American Football League. The following year, they switched to the competing National Football League, and remained until 1945, when they won the League championship. In 1946, the team moved to Los Angeles, based in part on poor attendance. Even the championship game couldn’t fill more than half the seats. Their departure didn’t leave Cleveland teamless; that same year, they got the Browns (named after Ohio State coach Paul Brown).

Upon moving to L.A., the Rams integrated African-American players as a condition of being able to use the Coliseum. With the Browns also choosing the take African-American players, the Rams helped open the League to a whole new segment of athletes and fans. The move also helped establish pro sports in L.A. and set the tone for many future teams to go west.

2. 1957: The Dodgers Move to L.A.

The Dodgers had been in Brooklyn since 1884, breaking the color barrier along the way when Jackie Robinson joined the club in 1947. After a number of rough years, they made it to the World Series in 1956, only to lose to the Yankees. The Dodgers’ majority owner, Walter O’Malley had encountered a number of obstacles acquiring land around New York for a new stadium, and the city of Los Angeles was simultaneously trying to entice teams to come west. After striking a deal with the city that allowed the franchise to build where they wanted, and to also own the stadium (rather than split it with the city), the Dodgers decided to move. One last roadblock came from the National League itself, which told the team they’d block the move unless another team went west. The Giants had been having their own stadium troubles, and it wasn’t long before both teams split for California. The double departure paved the way for the foundation of the Mets in 1962.

In a 2010 interview with WNYC, Michael Shapiro, author of The Last Good Season: Brooklyn, the Dodgers, and Their Final Pennant Race Together, summed up the impact of the move on the city: “What I came to understand is that what the Dodgers were about was a topic of conversation. That, in many ways, is what really makes cities work and what holds cities together . . .I think you can make a really powerful argument that what Brooklyn lost after the Dodgers left was a topic of conversation.”

3. 1960: Alliteration is More Important Than the Number of Lakes

The Lakers actually started with a move when Ben Berger and Morris Chalfen bought the Detroit Gems in 1947 and brought the team to Minneapolis. After a losing season that included the team surviving their plane crash-landing during a snowstorm, then-owner Bob Short decided to move the team to Los Angeles. They became the NBA’s first west coast team; in that inaugural year, star Elgin Baylor and rookie Jerry West led the team back to the playoffs, though they missed the finals by a basket. One interesting wrinkle about the move is that while the name “Lakers” was completely attributed to Minnesota’s 12,000 lakes, the name was preserved in the move, partially because of the nice alliteration.

4. 1982: The Raiders Begin Their Travels

The Oakland Raiders debuted in 1960 as one of the founding teams of the American Football League (which later merged with the NFL in 1970). In 1982, the Raiders moved to L.A., a change that lasted 12 years. At the outset of the 1995 season, they shifted back to Oakland, partially enticed by the city spending $220 million on stadium renovations. In 2016, billionaire casino magnate Sheldon Adelson put together a proposal for a new domed stadium in Las Vegas that would house both the UNLV team and a potential NFL franchise. Adelson held discussions with Raiders owner Mark Davis, who offered to contribute $500 million to the construction of the stadium if Las Vegas would also contribute. When Nevada legislators came through with $750 million in funding, Davis announced his declaration to move, a motion that was approved by the NFL. The Las Vegas Raiders are scheduled to kick off in 2020.

5. 1984: The Colts Sneak Out

After a lengthy and complicated run of cities, team names, and organization changes that stretched from Dayton, Ohio in 1920 through Brooklyn, Miami, Boston, and Dallas, the franchise officially became the Baltimore Colts in 1953. Over the years, conditions at Memorial Stadium continued to deteriorate, with seating, office space, and other amenities being inadequate for the needs of both the Colts and the Orioles baseball team, which shared the stadium. After years of struggle and attempts to get stadium improvements and funds, the city essentially said that they wouldn’t put in the improvements unless the Colts and Orioles signed long-term leases. The Orioles signed for one year; the Colts didn’t sign at all. The city of Indianapolis had begun construction of the Hoosier Dome, hoping to lure a team to the city; when they pitched Colts owner Robert Irsay, it had the desired effect. As the Maryland legislature attempted to pass a bill to seize the organization, Mayflower moving trucks rolled up to the Colts complex and moved the team equipment and belongings out. By the time that the legislature passed the eminent domain bill to seize the team, the Colts had made their way to Indianapolis. They became the Indianapolis Colts with the onset of the 1984 season, earning the enmity of Baltimore forever; however, they did endorse Baltimore receiving a franchise in the ‘90s, which eventually became the Ravens.

For some former Baltimore Colts, the move came as a savage betrayal. Legendary Colts quarterback and Hall of Famer Johnny Unitas severed all of his ties with the Colts organization after the move. He later threw his support behind the Ravens, recognizing them as the true legacy team. Today, a statue of Unitas stands outside M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore, a defiant reminder that some team moves are felt deeply by former players.

6. 2012: The Nets Get Out of New Jersey While They’re Young

The Nets began life as a charter team of the ABA, a presumptive rival to the NBA that debuted in 1967. In their first season, they were the New Jersey Americans. The next year, they moved to Long Island and became the New York Nets; they would win two ABA championships under that name. In 1976, the ABA collapsed and four teams merged with the NBA, including the Nets. They went back to the New Jersey in 1977 and became, of course, the New Jersey Nets. That lasted until 2012. As early as 2005, the Nets had announced their intention to move to Brooklyn, but financing, partnership agreements, and lawsuits among various parties spaced out both the move and the building of their eventual home, the Barclays Center. However, all the obstacles were cleared by 2012, and the Nets, like everyone else, moved to Brooklyn.

7. 2014: Ending 12 Years of Hornet/Bobcat/Pelican Drama

Sometimes, you have a fairly straight team move. Other times, you have a very confusing series of circumstances. The Charlotte Hornets debuted in the NBA in 1988 as an expansion team; that lasted until 2002, when the team moved to New Orleans and became the New Orleans Hornets. In 2004, the NBA placed a new expansion team in Charlotte, which became the Charlotte Bobcats.

An unintended side effect of the Hornets’ residency in their new city came in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when the storm seriously damaged New Orleans Arena. The team was forced to play in Oklahoma City’s Ford Center for the rest of that season and the next season before they could return home. However, their success in OCK allowed the Seattle SuperSonics to successfully move and become the Oklahoma City Thunder.

By 2013, the Hornets decided that they wanted to rebrand and give themselves a name more closely associated with NOLA. Ultimately, they decided that they would become the New Orleans Pelicans. The following year, the Bobcats took back the now-vacant Hornets to become the Charlotte Hornets once again. Today, the Pelicans, Hornets, and Thunder continue to be active, with the Thunder serving as a perennial playoff contender.

Questions remains if the NBA will return to Seattle. Though the Jet City did recently get the franchise for a new NHL team, NBA commissioner Adam Silver says that while he loves Seattle, getting the city another team isn’t a high priority for the league at the moment. Then again, from what we’ve seen, team moves will always be a possibility.

Featured image: The RCA Dome (originally the Hoosier Dome) was built to lure teams to Indianapolis; it was demolished in 2008 and replaced by Lucas Oil Stadium. (Josh Hallett, Wikimedia Commons via Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.).

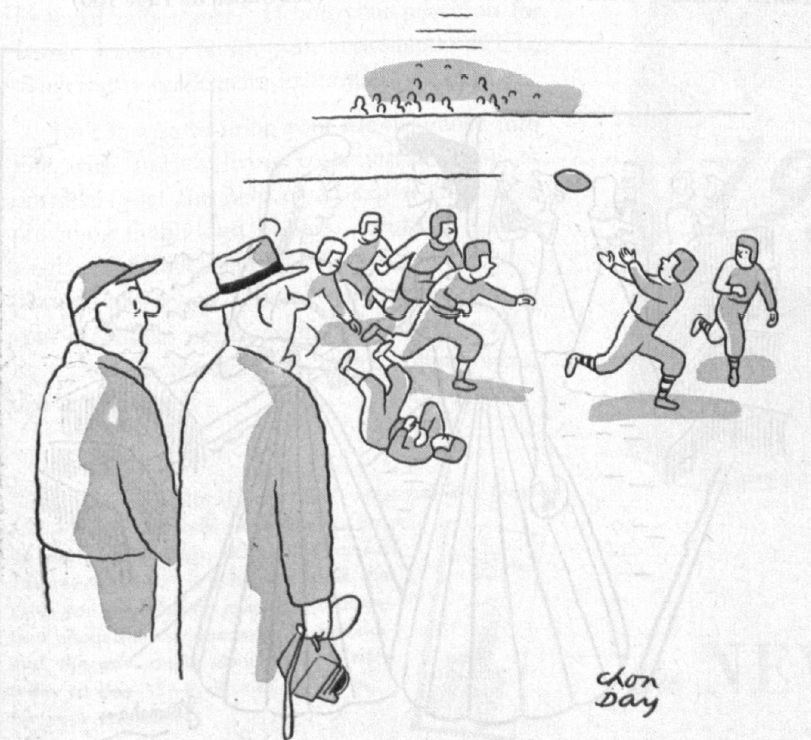

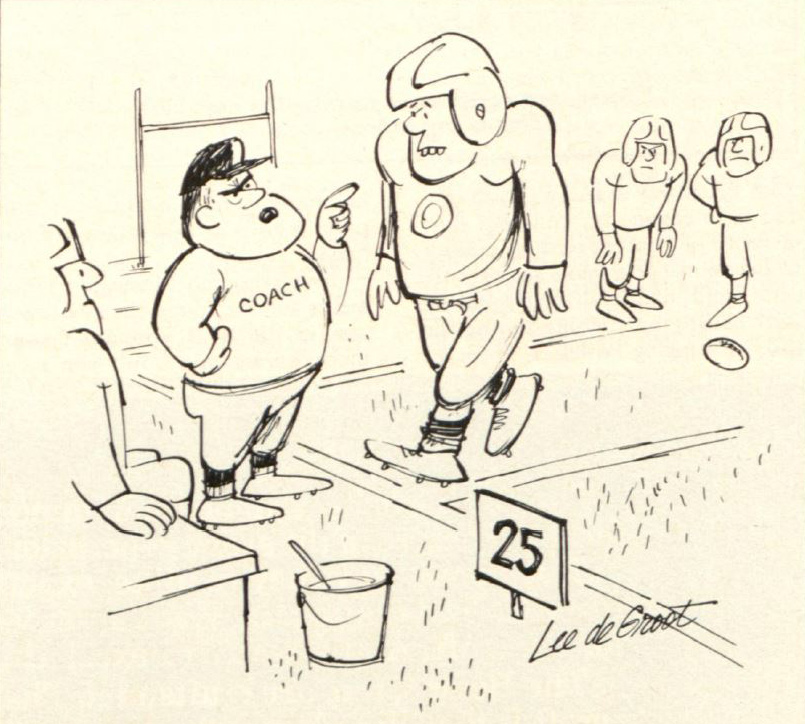

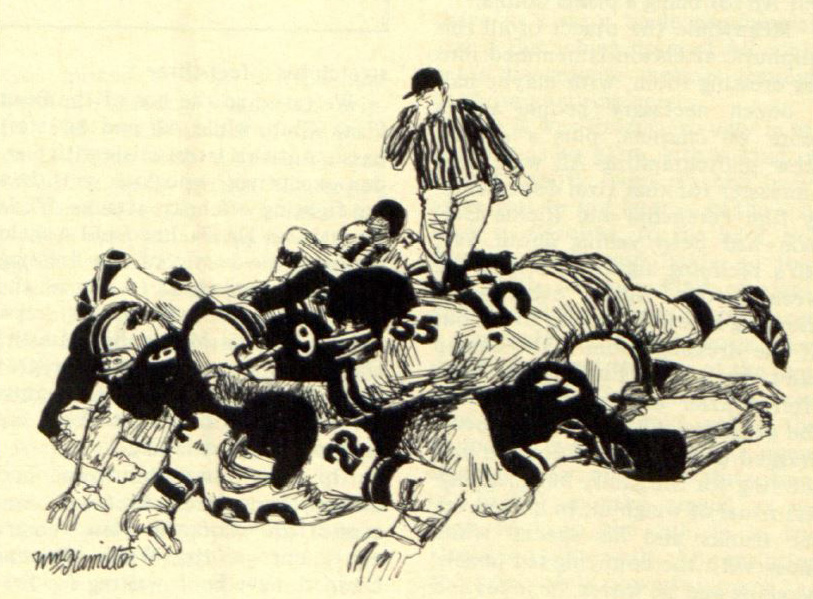

Cartoons: Football Fun

November 2, 1946

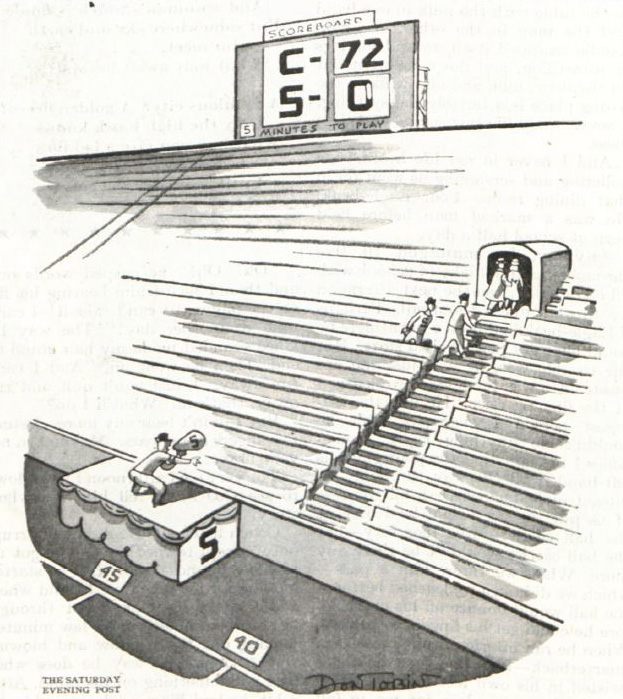

Don Tobin

October 19, 1946

October 12, 1946

Tom Henderson

October 12, 1946

November 16, 1946

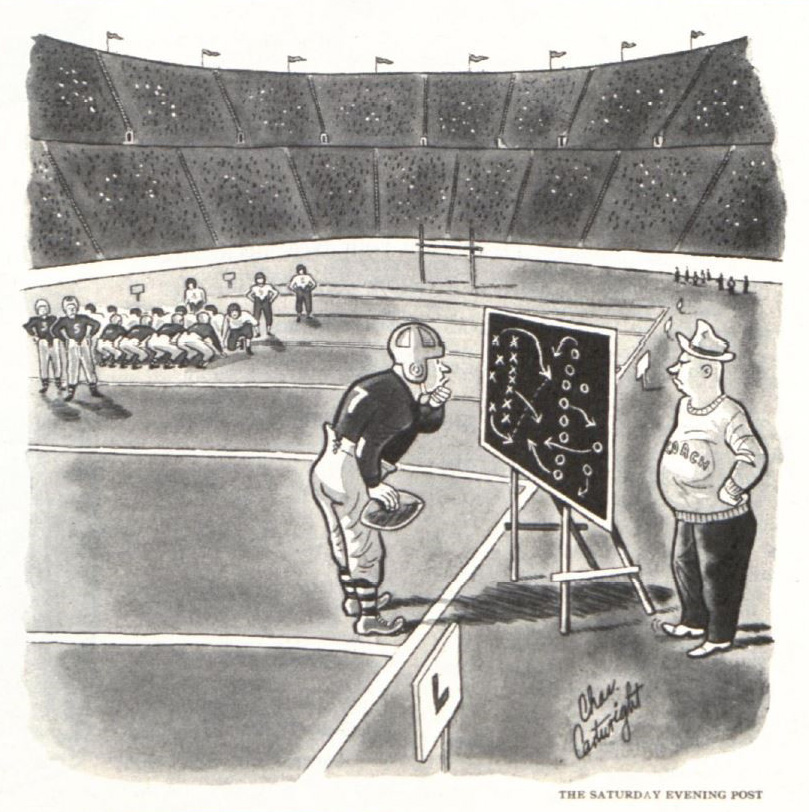

Chon Day

October 25, 1952

Lee De Grost

June 1, 1971

Hamilton

September 1, 1971

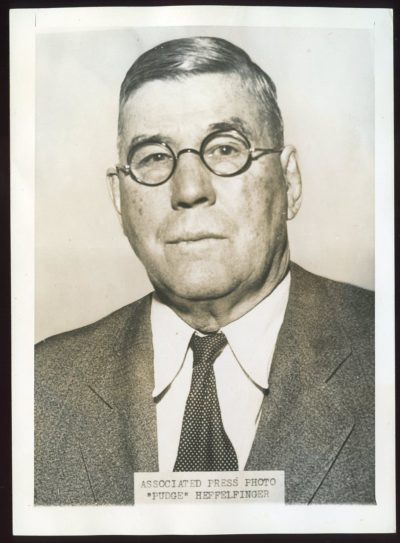

Considering History: Pudge Heffelfinger — The First Ever Pro Football Player

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

As the nation and world build up to the Super Bowl, always one of the most watched events of the year, it’s difficult to imagine a time when professional football wasn’t near the center of our cultural and social landscape. But the sport evolved through a series of distinct late 19th and early 20th century stages. But it was the career of one particularly prominent early football star named Pudge Heffelfinger that opened the door to pro football.

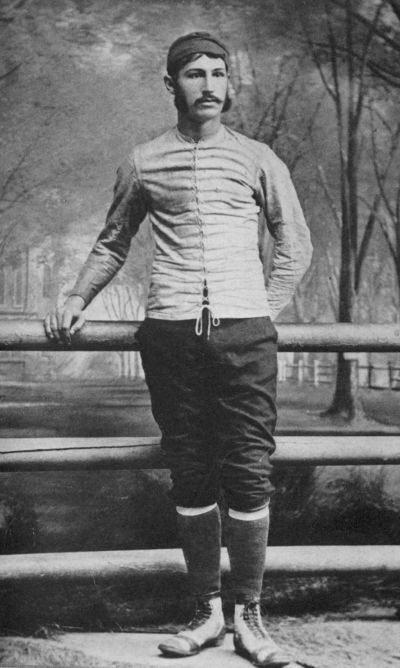

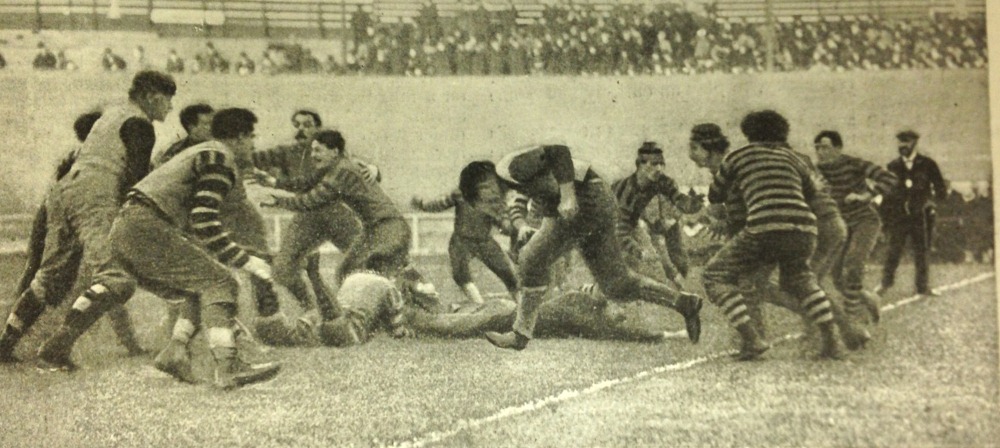

Invented sometime in the mid-19th century (as with baseball, the sport’s origins are hazy and contested) and played intercollegiately for the first time in 1869, by the 1880s football occupied a significant place in the national sporting scene. But the two central realities of football in the late 19th century are equally hard to believe today: that college football was pretty much the only game in town, and that at the center of the college football universe was the Ivy League, schools like Harvard and Yale.

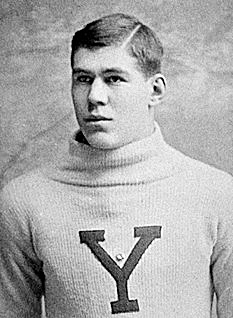

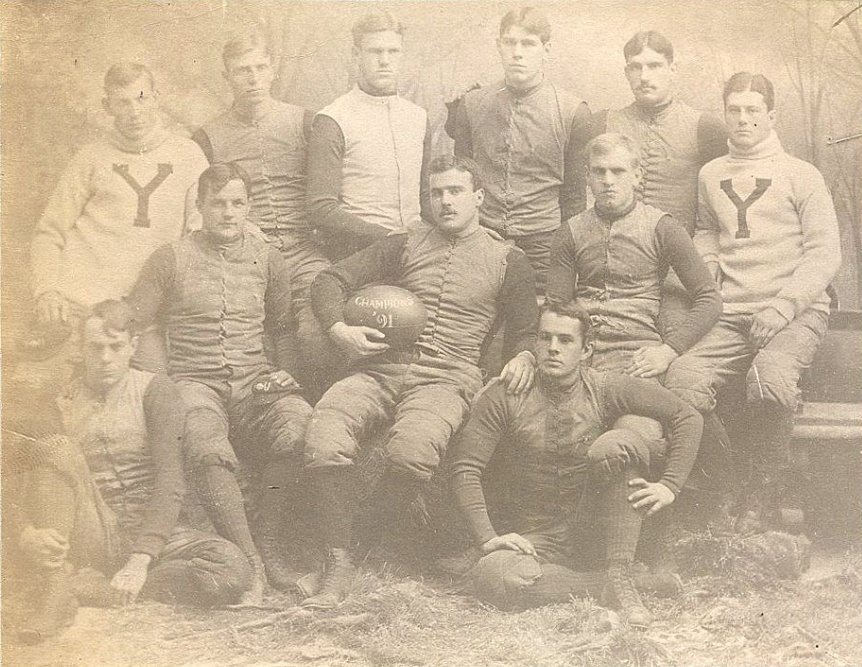

William “Pudge” Heffelfinger was born in Minneapolis in 1867, his father a Civil War veteran who had come by riverboat to the frontier city and opened a shoe factory there. A star athlete in high school, Heffelfinger went on to become a three-time All-American defensive guard during his four years at Yale (the 1888 to 1891 seasons).

Heffelfinger allegedly got off to a slow start – he was not aggressive enough, despite his 6’3” 210-pound frame. In order to motivate him, one of the assistant coaches wrote him a rousing letter in blood.

But it was under legendary coach Walter Camp, that Heffelfinger led the Yale team to undefeated seasons. The 1888 team, moreover, also gave up precisely no points on the season, outscoring its thirteen opponents 698 to 0 (for an average victory of 53.7 to 0). Few if any sports teams, from any era and at any level, have equaled the success of that Ivy League football squad.

Professional sports were beginning to emerge in America during that same late 19th century period; but when compared with the juggernauts that our major sports teams and leagues now are, they developed in a strikingly haphazard fashion. Both the historic paycheck that made Pudge Heffelfinger the first professional football player and the story of how that document was discovered embody that randomness.

In the 1960s, the Pro Football Hall of Fame, alerted by a rediscovered item from Pittsburgh newspapers, recovered a long-lost page from the account ledger of the Allegheny Athletic Association. That Association was one of many semi-pro organizations in the era through which former college stars like Heffelfinger could continue to play the game while pursuing their professional careers in other areas. But in late 1892, all that changed: the rediscovered ledger page reveals that Heffelfinger was paid both a $25 salary and a $500 “game performance bonus” by Allegheny to play in a game against the Pittsburgh Athletic Club on November 12, 1892.

It appears from the ledger and other sources that Heffelfinger was the only player paid to appear in that game, making him the first professional football player. Over the next few years, six other prominent players would be paid, some for individual games and some on salary for entire seasons. One of them was only 18 years old: John Brallier, who while quarterback at Pennsylvania’s Indiana College was paid $10 by the Latrobe semi-pro team for a September 1895 game against rival Jeannette. Such was the haphazard nature of “professional” sports in the 1890s, and yet these were the vital first steps toward the cultural behemoth that is the 21st century National Football League.

By the mid-20th century, both football in general and professional football in particular had become far more organized and wide-ranging. In his final role in football (after a few years of coaching at various universities and an unsuccessful attempt to take up the family shoe manufacturing business) Heffelfinger compiled and authored Heffelfinger’s Football Facts, an annual publication that featured statistics and schedules for both college and pro teams. This periodical, which was published between 1935 and 1950, was one of the first of the now-ubiquitous annuals created for every major sport. Heffelfinger’s Football Facts did more than just reflect football’s growth and popularity, though—it also helped contribute to those trends, using the name and identity of this iconic early star, as well as new 20th century journalism and media technologies, to publicize and sell the sport to familiar and new audiences alike.

In recent years, controversies such as concussion concerns and social protests have shifted the football landscape, and will no doubt continue to. But as Pudge Heffelfinger reveals, the story of football has been an evolving one from the outset.