Growing Up In America’s Heartland

By the middle of the 20th century, most Americans didn’t live in rural areas. Not even most Midwesterners. But I was born a fifth-generation Kansas farmer, roots so deep in the county where I was raised that I rode tractors on the same land where my ancestors rode wagons.

During the 1860s, the Homestead Act invited any adult citizens or immigrants who had applied for citizenship — including, at least officially, single women and freed slaves — to occupy and “improve” an immense area west of the Mississippi River in exchange for up to 160 “free” acres.

That land had been inhabited for centuries by native peoples, of course. Those tribes had been harmed by European raiders long before the United States was formed. But the late 19th century marked the devastation of the Plains tribes as the federal government strategically and violently “removed” their people and annihilated the bison herds they followed for sustenance.

Meanwhile, 1.6 million people, many of whom were poor whites, were welcomed west with the promise of land ownership. That was profit-motivated propaganda; the U.S. had given massive swaths of land to private railroad companies with the idea that the development they promoted and enabled would commercially invigorate the country from one coast to the other.

The concern was never about the people being summoned to farm the land. It was about turning land into a commodity and immigrants into its workers.

A handful of my ancestors came to the United States in the 1800s, stopped for a generation in Pennsylvania Dutch Country, and took on the Kansas prairie by the 1880s. They could have stayed in New York City, as so many did after crossing the Atlantic. Instead, they ventured into the so-called frontier.

I grew up not knowing about that history, because my family had a way of not discussing themselves or the past. The stories I know, I know because I asked again and again. But as a child I nonetheless absorbed the self-understanding that sustains a rural people who have grown and hunted their own food for a very long time. What I understood is that we were hard workers, and what we worked was the earth.

Many who tried that work as homesteaders didn’t last more than a few years on the prairie. They shot themselves in the head while blizzards buried their sod houses in drifts. They pushed farther west toward more verdant places when drought starved their crops and therefore their children. They took a Pawnee’s flint arrow to the thigh and died from infection. Intimate problems, all of them, but ones that stemmed from public policy: The federal government had given them land to work as though the arid plains were just like rich eastern soil, as though it was a great deal. By and large, it wasn’t wealthy folks who took the offer.

Those who managed to profit or at least subsist on their land soon saw the population tide turn. After the Homestead Act, it was only a matter of decades until the American industrial revolution made cities into hotbeds of economic potential. Factory smokestacks beckoned from city skylines, and agriculture became an option rather than a requirement for the underclasses. For some of them, a new system of state universities and land-grant colleges held the promise of higher education and work in office chairs, rather than on their feet.

But once my family got to Kansas, they stayed. They worked the land too hard and too fast for the soil to keep up, and the prairie wind buried their houses in dirt. Many people fled the Great Plains then, amid the Great Depression and black, hellish, roiling clouds of dust in the 1930s. Still, my family stayed. Maybe they wanted to leave but didn’t or couldn’t. I don’t know. But not even the Dust Bowl drove them out.

It wasn’t all bad. Though money was scarce, you would have had your basic needs met because we knew how to grow and build things.

By the 1950s, advancements in farming equipment finally allowed for the economic dream of something beyond mere subsistence. Farmers were working huge swaths of land, putting away a large surplus of grain that would be distributed around the world by way of new transportation infrastructure — ports, highways, and railroads the country had invested in.

Then came trouble with banks.

Land prices rose in the 1970s, and banks started granting farm mortgages using a farm’s productivity as collateral, regardless of a family’s ability to repay. When land prices fell during my 1980s childhood, collateral value did, too; interest rates spiked, and farms were foreclosed on in droves.

They called it “the farm crisis.” Family operations went under in record numbers, and federal farm bills didn’t stop the corporate and global forces that were devastating small farmers like us. During the first 10 years of my life, from 1980 to 1990, rural Kansas lost about 40,000 residents, while Kansas metro areas gained about 150,000.

That was the climate I came up in. All around us things were closing: the small-town department store, the hardware store with its tiny drawers stretching to the ceiling, the local restaurant. Lawyers took down their small-town shingles and doctors moved to cities.

But we held on.

It wasn’t all bad, that poor rural place. Though money was scarce, you would have had your basic needs met because we knew how to grow and build things. The popular image of Kansas is a monotonous, level expanse. If you drive through without getting off the interstate highway, that might be all you see for hundreds of miles, but some corners of Kansas are made of modest hills, woods, red-rock formations, slight cliffs. Still, my family fit the stereotype as both a people and a place: farmers on flat earth.

Some of us saw a beauty in that earth that people heading west toward the Rocky Mountains seemed to miss. But the earth was more of a tactile experience than a view. We had it on us. Cars got stuck in muddy ditches after thunderstorms. My feet got stuck in the marshy edges of ponds full of cattails. Gravel got stuck in my knees when my bike tires slid on roads made of sand.

We pulled radishes out of the garden, rubbed them on our jeans, and ate them right there if we pleased because a little dirt was good for you. After a shower, it was still under our fingernails and in the grooves between our toes.

We rarely bothered to wash our cars and pickups because they went up and down muddy roads every day and what was the point? What came out of the dirt went into the kitchen. Grandma Betty showed me how to chop vegetables, peel potatoes, pull guts out of chickens, and beat the eggs they laid.

Grandma breaded pork chops Grandpa had butchered and put them in a hot skillet while I stood on a kitchen chair in my underwear running a hand mixer through a bowl of boiled potatoes and milk.

We were country people in the middle of the country, living in a way that, I gather from things they’ve said to me over the years, some middle-class people in cities and suburbs on coasts thought had died long ago. For someone who never worked a farm, for whom the bread and meat in deli sandwiches seemed to magically materialize without agricultural labor, the center of the country was a place flown over but not touched.

“I haven’t heard of anything like that since The Grapes of Wrath,” people with different backgrounds would say to me in all seriousness when I described life on the farm. They thought we didn’t exist anymore, when in fact we just existed in places they never went. It was an easy way to think, I guess. I rarely saw the place I called home described or tended to in political discourse, the news media, or popular culture as anything but a stereotype or something that happened a hundred years ago.

We were so invisible as to be misrepresented even in caricature, lumped in with other sorts of poor whites, derogatory terms applied to us even if they didn’t make sense. We lived on the open prairie, so we weren’t the hillbillies of the Smoky Mountains or the Ozarks. We weren’t roughnecks in oil fields; Kansas had a humble tap on oil thousands of feet below the prairie, but nothing like Oklahoma or Texas to the south. Redneck and cracker didn’t quite translate, since their American usage was rooted in the slave South, against which Kansas had lit many of the fires that sparked the Civil War.

Slang terms for my plains ancestors who built dwellings there from sod, the only available material for lack of trees, didn’t survive in common vernacular. We were so willfully forgotten in American culture that the most common slur toward us was one applied to poor whites anywhere: white trash. Or, since we moved in and out of mobile homes, trailer trash.

But as members of all sorts of stereotyped groups know, the popular image — selected or fixated upon by someone more powerful than you — doesn’t tell you much about the life.

For one thing, anyone who has lived it knows that what matters less than the trailer is where the trailer is parked. Ours was in the country by my father’s choice, on the land where he later built our house. The place was thought boring for being grassland — mountains and forests being the landscapes that more often inspire awe — but without hills and trees we had a bigger sky than Montana, an unobstructed view of bright color between dark thunder clouds like nothing I’ve ever seen elsewhere. Those displays were so grand outside a single-wide metal dwelling on wheels that it felt less like us having a good view than like God having a view of us. I could feel how small we were.

I knew, so deeply that I wasn’t even conscious of it, that my family was on the outside of something considered normal. That normalized thing was the city, suburbs, even little burgs of 3,000 people. We called them all “town,” even the small ones seeming to lord over us when we wore dirty jeans to visit a bank teller wearing a suit from Dillard’s. Places with banks, schools, stores, and county courthouses — let alone skyscrapers — represented to us a sort of power we were removed from, a disenfranchisement not only by culture but by geographic distance. This bred in us a distrust of just about anyone who held a power we didn’t — even those who tried to help.

I rarely saw the place I called home described … as anything but a stereotype or something that happened a hundred years ago.

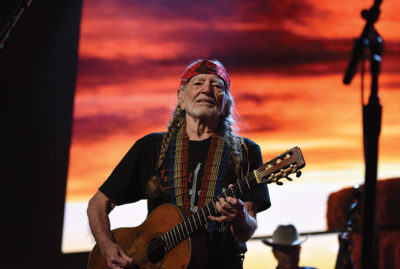

“I never seen a dime of it,” Grandpa Arnie would say about Farm Aid, the concert fundraiser begun in 1985 to save dying family farms. The founders were white singers from humble places: Willie Nelson, who was born the son of an auto mechanic during the Great Depression and spent the summers of his youth picking cotton in the Texas heat. John Cougar Mellencamp, who was born in small-town Indiana and became a grandfather at age 37. Neil Young — well, he was a middle-class hippie from Canada. Grandpa Arnie didn’t know or care about any of that. All he knew was that he’d never been to a big concert in his life, and he wouldn’t get to go to this one.

All around us, farm loans were underwater. Old farmers died and their kids sold everything off; many of them had already moved to cities, which their parents often encouraged for their survival. That economic collapse deepened a consensus within society that a talented person from the country would endeavor to “get out.” Some did. They got scholarships to college, blew town, and — their politics and economic prospects having changed — never looked back. That “rural flight” made way for the idea that country people can’t “make it” in a bustling metropolis. But the ability to measure distances for planting alfalfa and smell the right moment to cut it isn’t so different from the ability to map out a subway trip and feel when a stop has been missed.

Like all industrialized countries, America started out country and turned city. My people didn’t turn with it. Instead of striving toward glowing economic meccas, they stayed on tractors in fields, or in small towns where life struck many of them as not just good enough but preferable to bigger places. Often, it’s not that country people can’t hack the city but that they choose not to — or life just played out differently regardless of their desires.

When I was a kid, the U.S. was a few decades away from reckoning with the reality that the next generation would be worse off, not better off, than the one before it. But my community had been facing dwindling odds for generations. They knew that children like me likely wouldn’t and shouldn’t aim for life on a farm. Few country kids were pressured to keep a farm going.

Well ahead of middle-class America, for all my family’s emphasis on hard work, on some level we’d done away with the idea that it always paid off. Being as we got up before dawn to do chores and didn’t quit until after dark, it was plain that the problem with our outcomes wasn’t lack of hard work. The problem was with commodities markets, with big business, with Wall Street — things so far away and impenetrable to us that all we could do was shake our heads, hate the government, and get the combine into the shed before it started to hail.

Of all the forces that caused what social scientists call rural flight, the most powerful one during my childhood was perhaps industrialized agriculture, in which big farming operations with massive machinery churn out products. Small farms like my family’s, where the pigpen contained three sows and a litter of piglets, had no place in such an economy — one that was about more, bigger, faster.

In 1980, the year I was born, there were 65,000 hog farmers in Iowa, working out to about 200 hogs per farm; 32 years later, there were 10,000 hog operations with 1,400 animals each. Meanwhile, the grain industry consolidated, shutting down local co-ops. Rural jobs dwindled, people moved away, and the services and stores and schools that couldn’t be sustained by a hundred people boarded up.

There’s another sort of rural-urban imbalance, though: When so many people migrate to and populate cities that they experience over-crowdedness and high unemployment, sociologists call it overurbanization. For working people, the fantasy of the city can shake out just as poorly as 160 free acres of hard silt. That only became more true as I was growing up. Incomes kept falling, and costs kept rising. Cities were gentrified and became unaffordable.

It wasn’t just the death of the family farm you would have been born into but the death of the working and even lower middle classes, regardless of their place.

Somewhere along the way of America, people moved from farms to cities until the nation was a more urban place than a rural one. My father’s family had held out and held on for generations, though, preferring air to asphalt and lightning bugs to streetlamps. Or maybe they were just so far off the grid that they didn’t know any other life for comparison.

If I live to be an old woman and the trends of my early life continue, by the time I die, half the Kansas population will live in only 5 of 105 counties — people consolidated like seed companies. There’s a strength in that, environmentalists and economists might suggest, but perhaps a greater weakness.

President Dwight Eisenhower, a native of rural Kansas, said, “Whatever America hopes to bring to pass in the world must first come to pass in the heart of America.” The countryside is no more our nation’s heart than are its cities, and rural people aren’t more noble and dignified for their dirty work in fields. But to devalue, in our social investments, the people who tend crops and livestock, or to refer to their place as “flyover country,” is to forget not just a country’s foundation but its connection to the earth, to cycles of life scarcely witnessed and ill understood in concrete landscapes. For a sustainable world, one in balance both economically and environmentally, the American heart needs a strong, well-supported, well-respected chamber outside its metropoles.

The life force that flows back into it will likely be from other places. The meatpacking towns of western Kansas, for instance, have become some of the most ethnically diverse places in the country as immigrants stream in from Mexico, the Middle East, and Central America to take factory jobs amid industrial agriculture’s boom.

Statewide, according to the 2010 census, many rural counties had declined, and more than 8 out of 10 Kansans were white. But the Hispanic population had grown by 60 percent in the last ten years. That’s a demographic shift not without tensions but one that has been embraced by some small-town whites, who knew their home must change to survive. As Europeans who moved west and built sod houses on the prairie learned, you either work together or starve alone.

Of all the gifts and challenges of rural life, one of its most wonderful paradoxes is that closeness born of our biggest spaces: a deep intimacy forced not by the proximity of rows of apartments but by having only one neighbor within three miles to help when you’re sick, when your tractor’s down and you need a ride, when the snow starts drifting so you check on the old woman with the mean dog, regardless of whether you like her.

When I was well into adulthood, the U.S. developed the notion that a dividing line of class and geography separated two essentially different kinds of people. I knew that wasn’t right, because both sides existed in me — where I was from and what I hoped to do in life, the place that best sustained me and the places I needed to go for the things I meant to do. Straddling that supposed line as I did, I knew it was about a difference of experience, not of humanity.

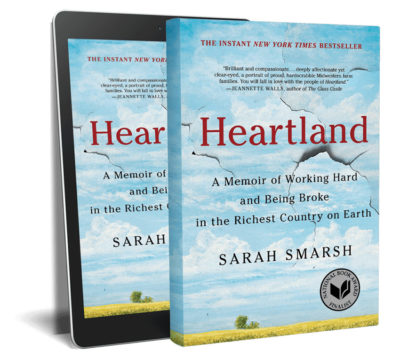

From Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth by Sarah Smarsh. Copyright © 2018 by Sarah Smarsh. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock