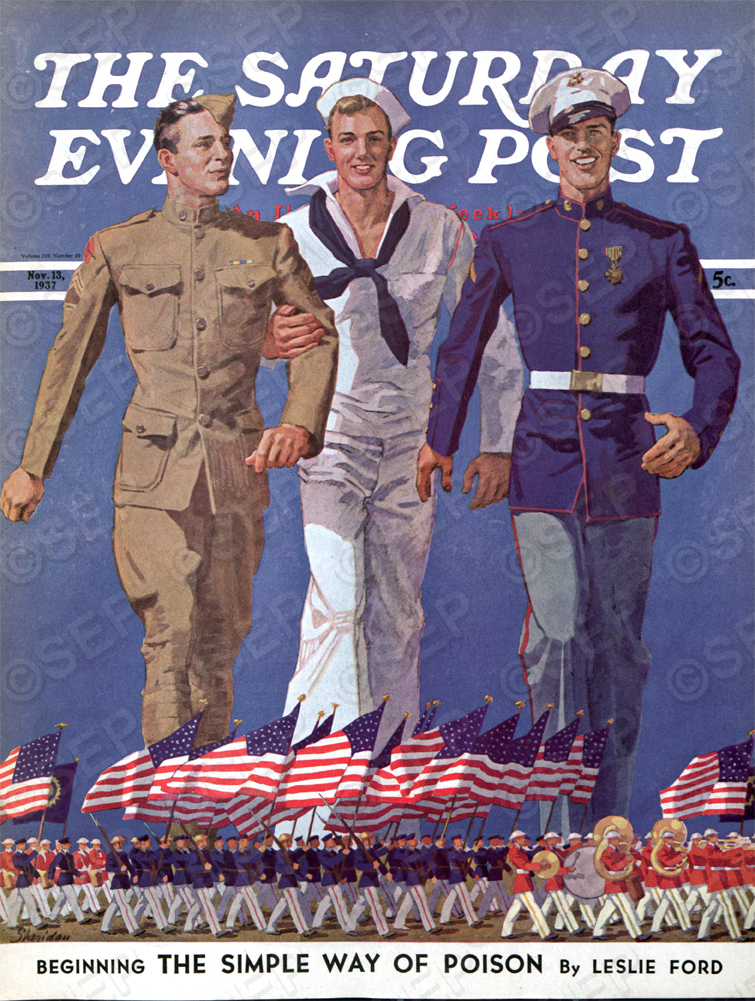

Tribute to Our Troops Essay Contest Winners

Thank you to all who participated in The Saturday Evening Post’s Tribute to Our Troops essay contest.

“The Saturday Evening Post, for nearly 300 years, has been proud to showcase the American way, and through this contest we honor soldiers past and present who risk their lives every day for our country,” says Steven Slon, editorial director and associate publisher. “We are very excited to present the inspiring tributes from our readers.”

Each of the winners will receive a watch courtesy of our co-sponsor Speidel.

“Speidel is very proud to have been a part of The Saturday Evening Post Tribute to Our Troops essay contest, and we offer our heartfelt thanks and congratulations to each of the winners,” said Lynn-Marie Cerce, co-owner of Speidel. “We would also like to thank all of our loyal customers—many of them Saturday Evening Post readers—who help us provide critically-needed financial support and services to members of the military and their families through our Change A Band, Change A Life™ charitable giving program.”

As part of the program Speidel is donating a portion of all sales proceeds, including purchases made online at speidel.com to Operation Homefront.

The following essays are the top 20 entries selected by the Post editors:

Honor Thy Brother

By Elizabeth Heaney

Walking through the battalion offices, I see a big, broad-shouldered staff sergeant intently focused on a dark blue uniform lying on his desktop. As I watch from the doorway, he leans over and places a narrow silver pin on the uniform’s chest. Before attaching the pin, he checks its placement in all four directions with a measuring device that calculates tiny, perfect millimeters.

After securing the pin, he checks each brass button down the front of the uniform in those same precise millimeters.

He’s wearing delicately thin white gloves on his huge hands, and touches the uniform gently, reverently. I’d seen soldiers prepare their dress uniforms to go up for promotion; this was different.

“Looks nice—you up for promotion?” I say from the doorway.

“No, ma’am. I’m escorting Tompkins’ body back to Iowa.”

Silence stretches between us.

“I’m so sorry you have to do that.” Then I add, “And I’m very grateful you will.”

“I wouldn’t have it any other way, ma’am. He was my soldier.”

Always a Hero

By Anne Linja

Navy Master Chief David Charles Linja—my husband, my hero—was holding my hand as we headed towards his retirement ceremony. There were many emotions and thoughts going through my mind. The most prevalent was “He’s coming home to us, our family. The U.S. may have had his heart, soul, and body for 30 years—and thankfully he stayed safe throughout all those years—but now he’ll be husband, dad, brother, son.”

As we stepped into the elevator, a fellow squid said, “Good morning, Master Chief!”

I responded, “He’s retiring today. It’s his last day.”

The sailor looked at me and respectfully said, “No, ma’am. He’ll always be a master chief.”

My husband suddenly had the biggest grin on his face, full of pride, knowing that he spent the last 30 years doing exactly what he was supposed to do.

Job Well Done

By Kathy Manier

While growing up in Orange County, I was always taught to thank our military for their service but never really had a full grasp of why I was thanking them—except for the obvious reason, fighting for my freedom.

Within the last couple years, I’ve personally come to know many service members, and their stories are humbling to say the least. To them, they are not heroes nor see any need to be thanked. They go to work every day like the rest of us—to do their job as best as they know how—except they don’t always get to come home at the end of the day.

They leave their families for months on end, work through holidays, and take the weight of the world’s problems on their shoulders. They sacrifice their safety, getting shot at, but for them it’s just another day at the office.

So for all the tears before each deployment, the PTSD that becomes the norm, the loved ones that are lost, the weeks of training in the middle of nowhere with no shower or bed, and the endless sacrifices they make on a daily basis, I thank them for their service, for just doing what they consider their “job.”

In the Steps of Our Ancestors

By Debbi Nelson

As a female child born into a lineage of proud males, I was raised on stories of ancestors who fought and died in the great conflicts—dating back to the American Revolution—of these United States. Images of draft cards and photos and the family stories still hold places of honor in my mind. As a youth, I could recite the stories, but, as an adult, I can feel them.

These were gutsy, in-your-face characters that hid their fears and left their families to benefit something bigger than themselves. Some never returned to their mothers or children. Some carried the horrors of war with them for the rest of their lives. But all of them watched with real pride each time the wind was slapped back by the Stars and Stripes. Their lives, and the lives of their comrades, were gifts that will never be forgotten.

Today, in big cities and small towns across this country, the tradition continues. I see young men and women putting their lives on hold in order to put on uniforms. The transportation and technology are different, but the American soldier is still the same, unafraid to defend. May God bless their every step!

No Thank You Required

By Greg Woodburn

After enjoying a wonderful meal on vacation with our two then-young children, we waited for our check.

Ten minutes became 30.

And we finally left without paying, but let me explain: Two businessmen across the room paid our bill, but requested we not be told until after they left. They saw a happy family, the waiter now explained, and simply wanted to do something kind with no thank you required.

Fourteen years passed, and then, last summer when I was leaving a local steak house, a U.S. soldier dressed in camouflage walked in.

“Hi,” I said. ”I want to thank you for all you do.”

“I appreciate that very much, sir,” the authentic American hero humbly replied while shaking my hand.

I wanted to say more, something less trite, but the table for two was ready and the hostess led the strapping soldier and his happy mother away.

I hope they ordered appetizers, wine to celebrate his homecoming, prime rib, plus dessert. And afterwards, I hope they had to wait a good long while, enjoying each other’s company and some laughs—even as they grew a bit impatient wondering where in the world their waiter was with the check.

A Hasty Prediction For the G.I. Bill

Its official name, when passed by Congress in June of 1944, was the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act, but it was soon renamed “the G.I. Bill of Rights.” While it provided several benefits to the veterans returning from World War II, the best remembered was the Reserve Education Assistance Program. Stanley Frank described the benefit in an August 18 issue of the Post:

Any man who has served in the armed forces for ninety days can attend for a year any approved school or college, and if he was less than twenty-five years of age at induction he is entitled to these benefits for a period equal to his military service after September 16, 1940, for a maximum of four years. The Government pays all bills for tuition and fees up to $500 a year.

It is a splendid bill, a wonderful bill, with only one conspicuous drawback. The guys aren’t buying it. They say “education” means “books,” any way you slice it, and that’s for somebody else. [“The G.I.’s Reject Education,” Stanley Frank, August 18, 1945]

He was right—partially, and only briefly.

As of February 1, 1945, only 12,844 discharged veterans throughout the country, in a total of 1,500,000, were attending schools under the G. I. Bill. Less than 1 per cent.

Frank had interviewed G.I.s at two veterans hospitals and found them anxious to get home and back to work as quickly as possible. Only 10% showed interest in further education. Most of these soon dropped out of the program.

Boiling down the figures, about 2 per cent of the amputees and neurosurgical cases—those who need it most—indicate an intention of having a go at serious, brain-building learning.

United States Army statistics prove that though [public education] has been free it hasn’t been popular. Only 23.3 per cent of the troops finished high school, and 3.6 per cent are college graduates. The average American soldier left school in the tenth grade, but … there are 5,000,000 in the armed forces who failed to graduate from grammar school.

Frank suggested the problem wasn’t schools, but “unchanging human nature”—i.e., most men don’t want to plan very far ahead in life.

We are, perhaps expecting too much of the tired, bewildered, embittered soldier, disassociated as he has been from civilian life, in asking him to plan his career. In normal times, most people have modest ambitions and are content to drift with the tide, evading responsibility if they can.

Though the college-benefit program had been in effect for a short time, some Post editor already saw the education benefit as a giant waste of taxpayer’s money.

Yet, by early the next year, there were signs of a general shift in Americans’ attitude toward education. Civilian adults, like the returning veterans, wanted to make up for the opportunities they’d lost during the war, and the Depression before it. Early in 1946, the Post reported “facilities of the country’s adult-education program are creaking under the load as [Americans] enroll by the hundreds of thousands.”

If, citizens have reasoned, a university can help practicing physicians, engineers, and so on, keep up to date, why can’t it tackle things that have ordinary folks stopped in their tracks?

A Gallup poll last spring indicated that 34 per cent of the adult population—25,000,000 folks—had the impulse to take advantage of part-time educational facilities after the war. [“Look Who’s Going To School Now!” Harold Titus, Feb. 9, 1946]

And just one year after the Post reported G.I.’s rejected education, it ran “Crisis at the Colleges.”

Heads of American colleges … are confronted with a reality that has always been a democratic dream: the opportunity to raise the educational attainments of a solid chunk of a whole generation. Because of the Government subsidy to servicemen, the opportunity is here; men who could never come to college under ordinary circumstances are enrolling or knocking at the doors.

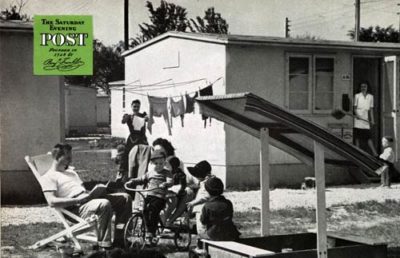

[However] the colleges do not have the facilities, the housing, the instructors, or classrooms to handle [the opportunity]. The primary, the immediate, the all-important, problem is housing.

Thousands of eligible veterans were turned away last September because the colleges had no place to quarter them; thousands more were turned away in February at the beginning of the second semester. And yet the enrollment of veterans rose immensely because the colleges did find some place, some way, to house some of them.

Here was the situation at Illinois during the second half of the school year. Total undergraduate enrollment at Urbana … was 12,780. This is more students than ever attended there before. … Total veteran undergraduate enrollment was 5509.

There were veterans living in basements, veterans in garrets, veterans in made-over garages and abandoned filling stations. There were 300 sleeping in double-decker beds in the gaunt building known as the Old Gymnasium Annex.

Gone is the campus where every prospect pleases… Cruelest blows to academic serenity are the clotheslines behind the trailers and prefabricated houses. Along with the leaves of the traditional whispering maples there are, diapers and children’s underpants blowing in the wind.

By the time the program ended in 1956, it had helped 2.2 million Americans attend college and another 6.6 million receive training.

It would be hard to over-estimate the effect on this country made by this wave of America’s college-educated G.I.s. It enabled these men to lead the changing industries of the post-war world. It also produced a higher expectation for education in the American public; a 10th-grade education became less socially acceptable in the growing middle class.

The G.I.-Bill generation passed its faith in education on to the next generation, which passed on to their children. It is still an article of faith to many Americans today despite the low employment rate of college graduates.