Considering History: Miriam Michelson and the Superwomen of the Suffrage Battle

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On May 21, 1919, the House of Representatives passed the 19th Amendment, prohibiting the states and federal government from denying the right to vote to U.S. citizens on the basis of sex, by a vote of 304 to 90. The House had passed the amendment one prior time, in January 1918, but that version had failed to secure passage in the Senate. This May 1919 passage, however, would on June 4 likewise pass the Senate, the crucial first two steps in the process that culminated with Tennessee becoming the 36th and final state to ratify the amendment on August 18, 1920.

That ratification represented the culmination of a far longer process still: the more than half-a-century battle of women’s suffrage activists to gain the right to vote for American women. In recent years, a good deal of attention has been directed to the divisions and flaws in that suffrage movement, including its frequent racism and segregation; indeed, a prior column of mine highlighted those darker histories.

Despite such shortcomings, the suffrage movement featured inspiring figures from every American community, strikingly impressive women who brought their unique experiences, perspectives, and voices to bear on not only the cause of women’s rights but every aspect of turn-of-the-century society. Far too often overlooked or forgotten, these women deserve prominent places in our national narratives. One woman who deserves such recognition is journalist and novelist Miriam Michelson. Through her articles on suffrage, gender relations, racism, and voting, Michelson used her writing to chip away at these barriers. Anew collection, The Superwoman and Other Writings by Miriam Michelson (edited and introduced by scholar Lori Harrison-Kahan), exemplifies these forgotten superwomen of the suffrage movement.

Miriam Michelson was born in a California mining camp in 1870, one of eight children of Samuel and Rosalie Michelson, a pair of Polish Jewish immigrants who had in 1855 fled anti-Semitic violence to join the Gold Rush. The family would settle in Virginia City, Nevada, where Samuel and Rosalie opened a store to supply the miners. By the age of 25 Miriam had begun her own journalistic career in that evolving Western society, working as a reporter and columnist for the San Francisco Call and San Francisco Bulletin. From these earliest pieces she challenged conventional narratives and advocated for progressive social causes, as illustrated by a September 1897 article for the Call, “Many Thousands of Native Hawaiians Sign a Protest to the United States Government Against Annexation.”

Women’s suffrage quickly became one of the causes on which Michelson’s newspaper columns most frequently focused, whether she was profiling individual leaders as in “The Real Susan B. Anthony” (1895), documenting the movement’s social and political gatherings as in “Viewed by a Woman: Miriam Michelson Gives Her Impression of the Congress” (1895), or linking suffrage to overarching arguments for equal rights and progressive identities as in “The Real New Woman: Miriam Michelson Likens Her to a Pleasant Dream, Not a Nightmare” (1895). In these and all her pieces Michelson brought nuanced observations and compelling style to the cause, making the case for equality as much through her own voice and perspective as through the content.

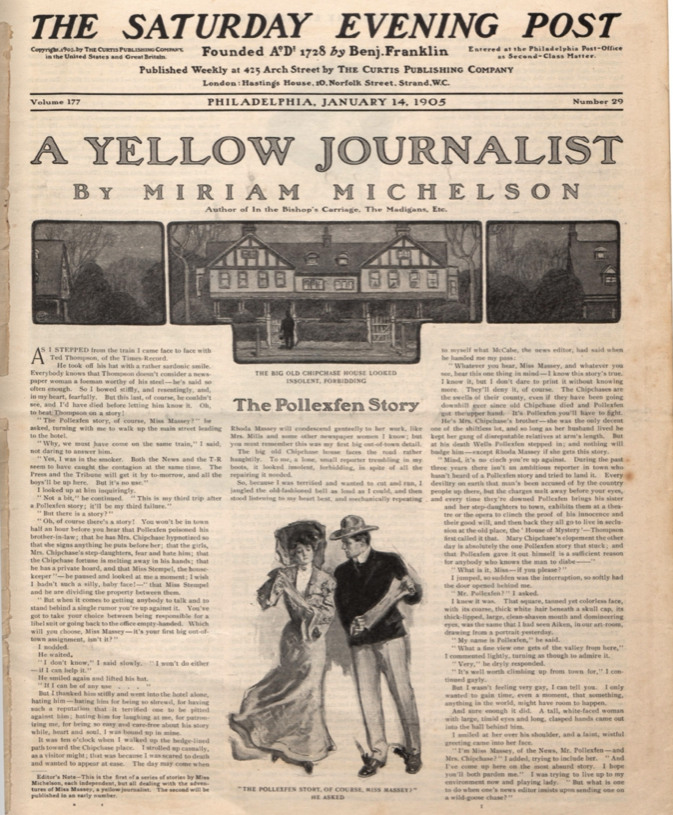

As Michelson’s career unfolded she turned to fiction as her central genre, but with that same combination of perspective, style, and progressive activism. One of her first novels, A Yellow Journalist (1905), was initially excerpted in several installments in The Saturday Evening Post and models the connection of her own career and perspective to these fictional stories. Yellow is narrated by Rhoda Massey, a hard-nosed young reporter, unconcerned with gender norms or expectations and determined to scoop her competitor Ted Thompson at all costs. Massey gradually becomes an impassioned social activist through the ethical and moral lessons offered by an older Jewish American woman whom she interviews.

Michelson extended such perspectives and themes to a quite distinct fictional genre with her novella The Superwoman (1912), a utopian fantasy about a matrilineal society in which early 20th century American gender roles and power dynamics are thoroughly and productively reversed. Throughout her career Michelson advocated for “The Matriarchate,” an alternative social order ruled by progressive female leaders modeled on both suffrage activists and the overall concept of the “New Woman.” In Superwoman she gave that theory extended imaginative shape and depth, creating a feminist utopia that predated by three years her colleague and friend Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 novel, Herland.

The ratification of the 19th Amendment did not, of course, usher in such a utopia, nor did it conclude the work and activism of figures like Miriam Michelson, who would continue to publish fiction, non-fiction, and journalism until her death in 1942. Yet the amendment represented a striking moment of progress and reflected decades of activism that led to that turning point. This singular and influential historical achievement would not have been possible without inspiring superwomen like Miriam Michelson.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons

Considering History: Vitriol and Violence, Radical Activism, and the Suffrage Movement

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

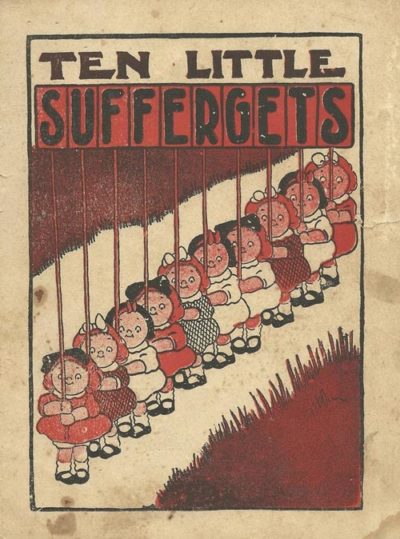

The early-20th-century children’s book Ten Little Suffergets (c.1910-1915) literally and figuratively illustrates the vitriol and violence often directed at the women’s suffrage movement and its participants. Based on the racist nursey rhyme “Ten Little Indians,” the book portrays suffrage activists as a group of spoiled young girls, carrying signs demanding such changes as “Cake Every Day,” “No More Spanking,” and “Down with Teachers” alongside “Equal Rights.” One by one the “suffergets” are either distracted by frivolous pursuits and abandon the cause or are violently removed from the march (such as by an angry father figure). The concluding image is of the final girl’s abandoned “dolly” (looking quite like the girl herself) with a cracked and broken head.

It’s possible in hindsight to see a now broadly accepted cause like women’s suffrage as being widely accepted and shared, as a significant political change that took time to achieve but without the kinds of hostile responses other such social movements have received. But in fact, across its more than half a century of existence, the American suffrage movement was quite the opposite: a profoundly radical and progressive idea that was subjected relentlessly to both rhetorical and actual attacks. Remembering those attacks always helps us consider the consistent courage of suffrage activists in facing such harassment and arguing for their cause, often in the most public places and ways.

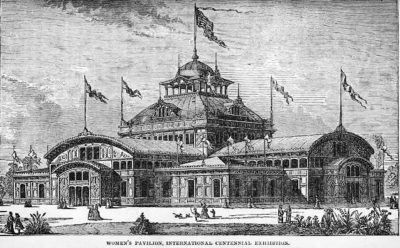

The July 4, 1876 protest at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia was one such occasion. For the first time at a World’s Fair, the Centennial included a separate Women’s Pavilion, a space in which to celebrate and share women’s identities, art and culture, and voices. Yet this impressive step was not without its limits, and one was the near-complete absence of any social or political issues — including the era’s most prominent such issue, suffrage — from the pavilion. Indeed, focusing more on domestic arts and crafts and housework, the Women’s Pavilion could be said to reinforce some of the most prominent arguments against women’s participation in the public and political spheres.

A group of suffrage activists, representing the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), decided to highlight this exclusion and their cause at the Centennial’s most public occasion, the July 4th celebration. Led by Susan B. Anthony, the group erected a stage of their own not far from the celebration’s official platform, and there read aloud a “Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States” (a revision and extension of the declaration produced at the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman’s Rights Convention). Before doing so, Anthony made clear the group’s willingness to confront their fellow Americans in this most public space, noting, “While the nation is buoyant with patriotism, and all hearts are attuned to praise, it is with sorrow we come to strike the one discordant note, on this 100th anniversary of our country’s birth.” Yet she added, “Our faith is firm and unwavering in the broad principles of human rights proclaimed in 1776, not only as abstract truths but as the cornerstones of a republic.”

Anthony, the NWSA, and their many colleagues continued to strike their discordant note and fight for the extension of those rights for the next four decades. Another very public moment of radical activism, and one met with particularly violent response, was the March 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade. Held in Washington, DC, on the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, the parade represented the largest gathering of suffrage activists and allies in American history, with more than 5,000 participants marching down Pennsylvania Avenue.

The marchers were met with sustained hostility, not only from many in the crowd but also from at least some of the police officers tasked to protect the parade. Hundreds of marchers were seriously injured; according to one eyewitness testimony quoted in The Washington Post, two ambulances “came and went constantly for six hours, always impeded and at times actually opposed, so that doctor and driver literally had to fight their way to give succor to the injured.” Yet the marchers, led by prominent activist Alice Paul and attorney Inez Milholland (riding a white horse), persevered, completing their planned route from the Capitol to the Treasury building, and drew national attention to both their cause and the violent attacks upon it.

The parade also featured an internal discordant note that produced one more moment of radical courage. The organizers intended the march to be segregated, with a separate cohort of African-American suffrage activists bringing up the rear. The pioneering journalist, anti-lynching crusader, and women’s rights activist Ida B. Wells asked if she could march with the Illinois delegation in the main march, and was initially turned down. Yet Wells did not accept this answer and, with the aid of sympathetic allies, defied this racist division and joined the Illinois delegation as the march began. In so doing, Wells embodied one more moment of radical persistence in the face of contempt and exclusion, a historical lesson that the American suffrage movement offers consistently and crucially.