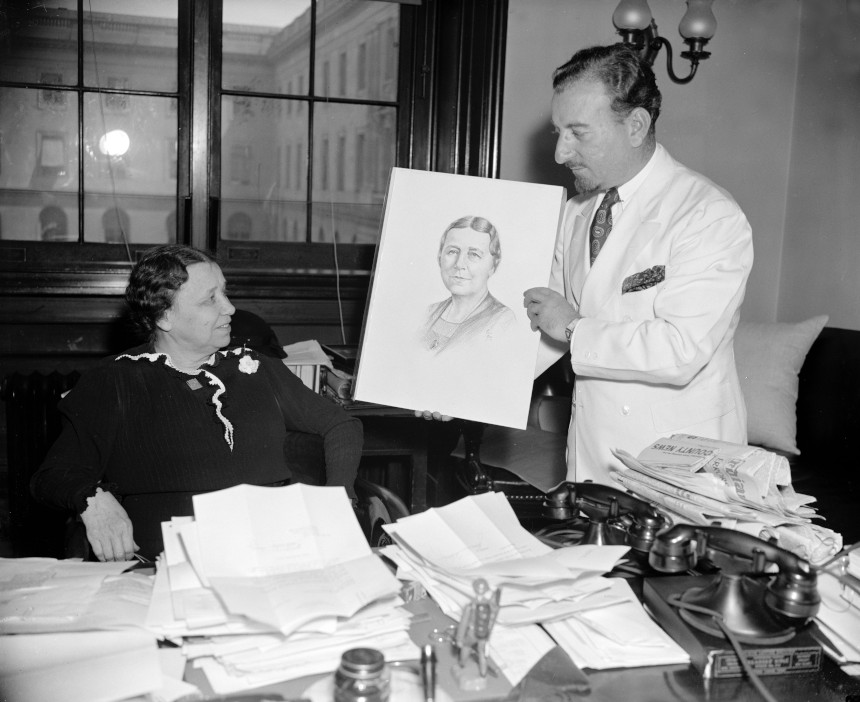

Mrs. Caraway Goes to Washington

The first woman elected to the U.S. Senate is not a household name. That woman, Hattie Wyatt Caraway of Arkansas, kept a very low profile. She is not considered a political trailblazer. Indeed, she voted with the rest of the Southern delegation against the Anti-Lynching Bill of 1934, intended to make lynching a federal crime. But though her name has become a historical footnote, Caraway, who was born in the shadow of post-Civil War Reconstruction and died at the dawn of the atomic age, offers a fascinating study in the challenges facing women in American politics.

Caraway won a special election to the Senate in 1931 after the death of her husband, Democratic Senator Thaddeus Caraway. This was not without precedent for a politician’s widow, because the move allowed the “real candidates” — the men — time to prepare their campaigns. But Caraway, at age 54, shocked the powers-that-be by announcing her plans to run in the 1932 general election.

In making the decision to run for a full term in the Senate, she knew she was breaking new ground for women. Until Caraway’s election, only one other woman had even set foot in the Senate, the self-styled “World’s Most Exclusive Club”; in 1922, 87-year-old Rebecca Felton had been allowed to sit in the chamber for a day as reward for her political contributions in Georgia. Though the 19th Amendment guaranteeing American women the right to vote had been ratified, the idea that government was a man’s sphere had not changed much since abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Sarah Grimké visited the U.S. Supreme Court years earlier in 1853. After Grimké was invited to sit in the Chief Justice’s chair, she stated that someday the seat might be occupied by a woman. In response, “the brethren laughed heartily,” she later recounted in a letter to a friend.

A widespread criticism of Caraway as she entered the 1932 campaign was that she was needed at home to take care of her children, even though they were already grown.

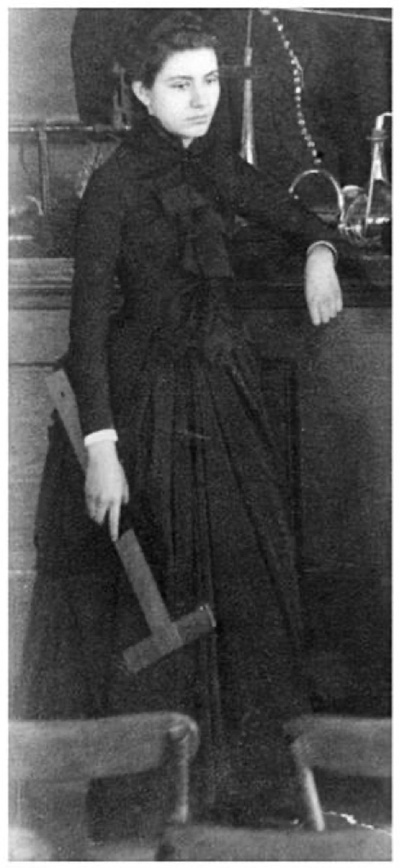

But in 1932, the year the Dow Jones hit its lowest point during the Great Depression, few Americans were laughing. Caraway, a small woman who always dressed in black after her husband’s death, could have easily passed as someone’s visiting grandmother in the halls of the Capitol. Her only previous elected experience was serving as the secretary of a small-town women’s club. But desperate constituents in Arkansas didn’t seem to care who she was, as long as she could help them.

Letters poured into Caraway’s Senate office, pleading for relief. As she read them and observed the action — or inaction — of fellow senators, she came to a startling revelation: Wasn’t a person — any person, even a woman — of moderate intelligence who worked hard, cared about average people, and stayed awake at their Senate desk (many colleagues didn’t) just as useful as those who made bombastic speeches?

Caraway’s three sons, West Pointers and high-ranking Army officers, supported her political aspirations. As she wrote in her journal entry of May 9, 1932, the first time she announced her decision to run: “Well, I pitched a coin and heads came three times, so because [my sons] wish and because I really want to try out my own theory of a woman running for office, I let my check and pledges be filed. And now won’t be able to sleep or eat.” Within two days’ time, though, Caraway seemed to have made peace with the decision, writing in her journal that she would “have a wonderful time running for office” if she could hold on to her dignity and sense of humor. During the campaign, she would need both.

A widespread criticism of Caraway as she entered the 1932 campaign was that she was needed at home to take care of her children, even though they were already grown. Sexism aside, Caraway’s campaign faced another problem: She had no money to run. But she did have a good friend in the flamboyant Louisiana politician Huey Long.

Long genuinely liked Caraway after spending time sitting next to her in the back row of the Senate, and he didn’t have much to lose by throwing his support behind her. Even if Caraway lost, it would not really be considered his fault since the odds were against her winning anyway. But if he were to help her get elected, he would emerge as a political miracle worker, and maybe even secure a rubber stamp for his pet programs. At the very least, he’d gain some ground in his power struggle with Arkansas’s other Senator, Joe T. Robinson.

With Long’s support, Caraway did win the 1932 election for a full term in the Senate, earning more total votes than all six men who ran against her put together. Some political observers said she would not have won without Huey’s help, but she notably defeated her opponents in counties where she and Long did not campaign.

In office, Caraway was dubbed “Silent Hattie” because she rarely delivered the thunderous orations her male colleagues were known for. It should be noted that there were male senators who declined to make speeches as well, but it was Caraway whose silence was labeled.

If she was quieter than most, her record spoke for her. As a senator, she worked tirelessly, earning a reputation as an effective public servant in the troubled times of the Great Depression and World War II. A saying among Arkansans became, “Write Senator Caraway. She will help you if she can.”

Caraway did her best work in committee, where she could speak normally without having to orate from the well of the Senate chamber. In this small setting, she could work to convince others of what average people needed, like flood control. She had seen the devastation in her state when roaring waters washed away entire communities during the Great Flood of 1927, the most destructive flood ever to hit the state and one of the worst in the history of the nation.

In office, Caraway was dubbed “Silent Hattie” because she rarely delivered the thunderous orations her male colleagues were known for.

When Caraway first ran for office, she ran on the premise that the nation could be served by an average person who knew the price of milk and bread, and who remembered there were people who had none. She walked her talk, carrying her lunch in a brown paper bag, and starting each day by reading every word of the Congressional Record. She never missed a Senate vote or a committee meeting. Nor did she take time away from Congress to campaign, as others did.

In time, she proved to herself that she had a mind as good as anyone’s in the Senate. While serving on the Senate’s Agriculture Committee, for instance, something that was important to her rural state, she realized that she knew firsthand about issues that affected farmers more than what she called in her journal the “manicured men” of the Senate.

The voters of Arkansas, in turn, stood by her. Caraway was reelected in 1938, defeating a strong candidate whose campaign slogan boomed “Arkansas Needs Another Man in the Senate!” She therefore became not only the first woman to be elected to the Senate, but also the first to be reelected. Among her many firsts serving in the Senate from 1931 to 1945, she also became the first to preside over the Senate, chair a Senate committee, and lead a Senate hearing.

But it wasn’t easy being the only woman in the room. Caraway was often ignored by her fellow senators, and she had no mentor. Her position must have often felt insecure. Arkansas’s other senator, the powerful Joe T. Robinson, had very few interactions with her. She presumed it was because he was waiting for a “real” senator — a man — to arrive. Several of her journal entries reflect their terse relationship. On January 4, 1932, soon after Caraway entered the Senate, she wrote that Robinson “came around only for a moment at the instigation” of his chief-of-staff. On May 19, 1932, Robinson inspired her to write, “I very foolishly tried to talk to Joe today. Never again. He was cooler than a fresh cucumber and sourer than a pickled one.” Reflecting on their strained relationship, she once poignantly confessed in her journal, “Guess I said too much or too little. Never know.”

If she felt invisible in the Senate chambers, she was very aware that the press held her in the spotlight. At one point, she wrote in her journal, “Today I almost made the front page as I lost the hem out of my petticoat.” But Caraway didn’t view herself as a firebrand. Rather, she conducted herself as she believed a “Southern lady” would do. In her journal, she notes that she did not appreciate when a reporter “pushed into” her office. “I was terribly indignant,” Caraway wrote. “She got no interview.”

Still, in 1943, she notably cosponsored the Equal Rights Amendment, a piece of legislation that had already been introduced in Congress 11 times and failed each time. The proposal simply read, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Caraway was also one of the sponsors of what has been called the most momentous piece of legislation in American history, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, popularly known as the GI Bill. In doing so, she put herself up against powerful congressmen who condemned the bill for being “socialist.” But Caraway, who came from a struggling farm family herself (she had only been able to go to college thanks to the generosity of a maiden aunt), firmly supported the piece of legislation, which contained educational benefits for World War II veterans. She saw it as a manifestation of her belief that education was the key to progress.

By 1944, however, Caraway’s style no longer resonated with voters in the same way. During her bid for reelection, she placed fourth in the Democratic primary. The winner, J. William Fulbright, a wealthy former Rhodes scholar, went on to secure the general election and would serve as a powerful force in the Senate for the next 30 years.

On Caraway’s final day in the Senate in 1945, her years of service earned her the rare standing ovation by her all-male colleagues. Yet, even as they honored her, a statement — which was no doubt meant as a compliment — offers a telling window into what it was like to be the first. “Mrs. Caraway,” one of the men proclaimed, “is the kind of woman senator that men senators prefer.”

More than a half-century after Caraway’s death in 1950, the challenging reality of her precarious position as the first woman to break into the “World’s Most Exclusive Club” still resonates. A few years ago, I was sitting next to Arkansas Senator Blanche Lincoln at a speaking engagement when the Senator opened her daily planner. Inside the front cover, where she would see it immediately, Senator Lincoln had written the words Caraway had written in her diary when she decided to run for the first time: “If I can hold on to my sense of humor and a modicum of dignity I shall have a wonderful time running for office, whether I get there or not.”

Nancy Hendricks writes extensively on women’s history and is the author of Senator Hattie Caraway: An Arkansas Legacy.

Originally Appeared at Zócalo Public Square

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Library of Congress

How Nebraska Farmer Luna Kellie Was Radicalized Before the 1896 Election

In the late 1800s, one Nebraska farmer was beleaguered by an unruly farm, ten children, corrupt bankers, and indifferent politicians. She could have given up. But instead, Luna Kellie did something about it.

For most members of the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance, a political advocacy group, the work of organizing occurred solely during the Alliances’ meetings and events. Yet for Luna Kellie, the Alliance’s secretary, the work often continued until the wee hours of the morning. As she later wrote in her memoirs, “if I had extra time when others were asleep, I would devote it to writings for the papers.” Kellie’s work for the Farmers’ Alliance eventually drove her to become a leader in the larger populist movement that swept through the U.S. during the 1890s. Yet even as she took on more responsibility, her political life and home life continued to intersect in the same way they had during those late night writing sessions. While Luna Kellie is far from being the most famous of the populist leaders, hers is the story of a woman driven to political action by personal hardship, making it particularly emblematic of the American political climate in the lead up to the pivotal 1896 presidential election.

St. Louis was a crowded town in 1876, and both Kellie and her husband J.T. felt that their dream for a safe and prosperous life was becoming more and more improbable in the industrializing city. So when the couple read a railroad advertisement for cheap homestead mortgages in Nebraska, they jumped at the opportunity. As Kellie wrote, “It seemed to me a great chance to see a beautiful country like the pictures showed and have lots of thrilling adventures.” A new life on the prairie also carried with it the promise of financial stability, a safe home, and a happy family. But in reality, Kellie’s new life was anything but the Little House on the Prairie. Instead, the newly Nebraskan farmer found that her farm’s success and her family’s well-being were at the whims of railroad magnates, cutthroat capitalists, and financiers in faraway states.

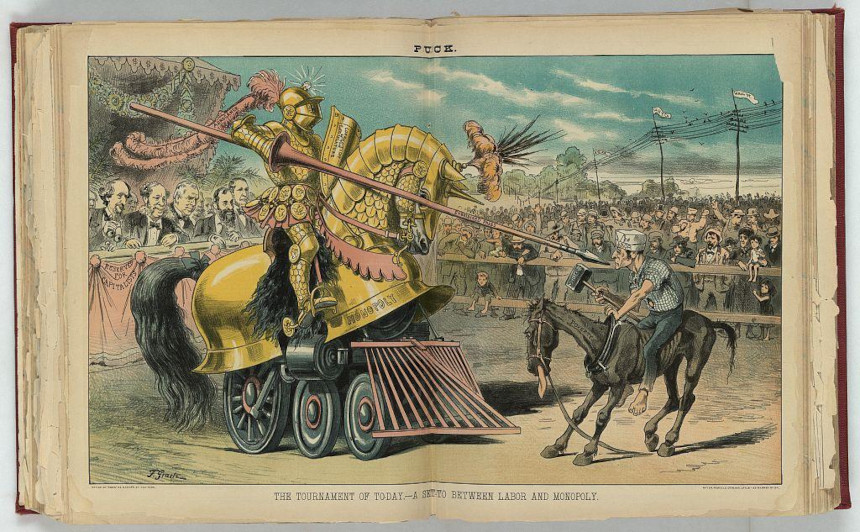

The decades after the Civil War promised a better life. Yet while the end of the 19th century was a time of widespread expansion, it was a time of even more widespread corruption. For freed African Americans, this corruption came in the form of Jim Crow regimes and new systems of oppression. For immigrants, it was political machines and decaying slums. For farmers — such as Kellie — corruption was apparent in the practices of railroads and banks that jockeyed for economic dominance over the vast expanses of the America west.

The end of the 19th century is called the Gilded Age on account of the decadence exhibited by urban capitalists such as Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller, yet this same monopolistic impulse extended across the country. Kellie was quick to point out how such corruption was at play in Nebraska, writing that

even after they [the railroads] had made 4 times the necessary ‘expenses’ had they [only] been content with a profit of 1 million a month instead of 2. If they knowing the farmers were raising their stuff for them below cost of production had said we will divide the profit on each haul of wheat and corn each carload of stock with you we would not only [have] been enabled to keep our place and thousands more like us but would have been enabled to live in comfort and out of debt.

One bad harvest was all that stood between most farmers and financial ruin, a fact that hung like a shadow over Kellie and her family. Midwestern homesteads were plagued by environmental hazards, ranging from crop-eating grasshoppers to tornadoes and disease. Kellie experienced all of these trials, with the extra challenge of raising ten children at the same time. Additionally, the mortgage on Kellie’s homestead was handled by an apathetic bank in distant Boston. As the bank continued to raise interest rates, Kellie and her family faced the very real possibility of losing their land entirely. To combat this fear, she began selling vegetables in nearby towns as a source of supplementary income, yet she knew that quick cash was not enough to remedy the challenges her family faced. She had realized that her failure to find success and happiness in Nebraska was the result of an economic system that disempowered prairie farmers for the betterment of railroads, banks, and the bottom line. And so Kellie turned her energy towards organizing.

Farmers around the country were beginning to identify the systematic roots of their poverty (including Kansas farmers who eventually brought their issue to the House of Representatives). However, both major parties were controlled by northern industrialists who had no inclination to support homesteaders. As a result, the populist movement emerged in different pockets throughout the country, eventually coalescing as a third-party option to fight for the livelihood of farmers.

Though it may not have been clear at the time, Kellie was at the forefront of the populist movement in Nebraska. Both she and J.T. were members of the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance, an organization that held town hall meetings and created literature that offered Nebraska homesteaders a voice in national politics. However, Kellie insisted that “the alliance at this time was not supposed to be political.” Instead, it was simply defending the work and lives of prairie farmers.

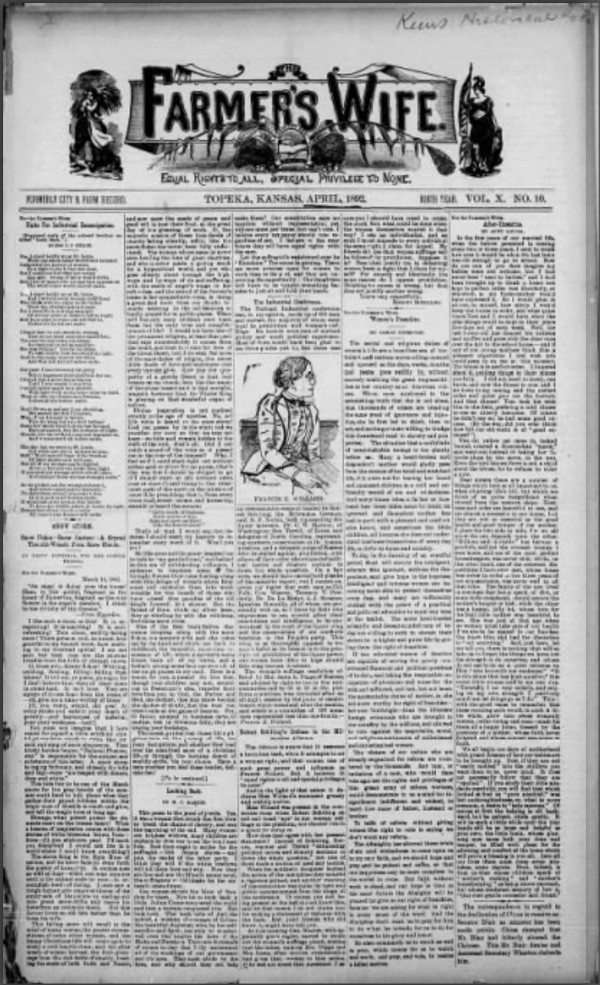

Still, Kellie continued to become more involved (much more than her husband) in the Farmers’ Alliance. She was elected as the organization’s secretary and took on the job of editing the Alliance’s newspaper, The Prairie Populist. In the paper, Kellie published biting condemnations of the railroads, bankers, and economic practices that had caused her family so much hardship. Her political awakening also extended beyond the needs of farmers. Kellie’s agency in the Farmers’ Alliance made her increasingly adamant about the need for women’s suffrage, and she soon took on the additional task of traveling to conventions around the country to fight for the vote. As The Scranton Tribune noted of one of her speeches, she “exerted her influence in favor of universal suffrage, undaunted by the fact that she was obliged to carry her baby with her during the long journey.” Kellie took on all of these new responsibilities while continuing to work on the homestead and raise her children, a feat that only strengthened the intensity of her political engagement.

As she traveled, Kellie earned a reputation for her fiery speeches. She was a songster, a type of public speaker who wrote political lyrics to well-known folksongs and would intersperse bits of verse throughout addresses. Luna traveled throughout Nebraska and its bordering states, engaging audiences of like-minded farmers with her urgent, song-infused speeches. The most notable of Kellie’s addresses was her “Stand Up for Nebraska” speech, which featured passionate lyrics about the deplorable practices of business monopolies and the financial security that Nebraska’s land should have provided:

Stand up for Nebraska! and shame upon those

Who fear the extent of their steals to disclose.

Who say that she cannot grow wealth or create;

But must coax foreign capital into the state.

Such insults each friend of the state deeply grieves:

Stand up for Nebraska and banish her thieves.

Through the Farmers’ Alliance, Kellie found her political voice to speak against the “foreign capital” of railroad companies and the larger wealth gap that was present throughout the United States. However, as the populist movement ballooned into a national third party, Kellie was quick to realize that the local roots and honest message of the Farmers’ Alliance was being corrupted. In the lead-up to the 1896 presidential election, the wildly successful populist candidate William Jennings Bryan agreed to combine forces with the Democratic Party and run as their candidate. So-called “fusionists” were in favor of this decision. People like Kellie, who believed that the populist movement’s central mission of helping farmers was being betrayed, did not.

Kellie continued organizing for the Farmers’ Alliance, but her premonitions were partly realized. Bryan lost the 1896 presidential election, and soon thereafter the Populist Party lost steam. It was perhaps the movement’s only chance at success on a national scale, and it was squandered. The community organizing that was the bread and butter of the populist movement faded into obscurity, and soon enough the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance also disbanded. Kellie continued speaking at conventions and fighting for women’s suffrage, but her political fervor waned.

Kellie continued working on her homestead, and many years later wrote a memoir for her family (which has since been published and serves as the principal source for this article). Quite poetically, she scribed the story of her life on the back of unused Farmers’ Alliance certificates. In its closing pages, Kellie offers a disillusioned soliloquy to the results of her political work. She writes, “And so I never vote [and] did not for years hardly look at a political paper. I feel that nothing is likely to be done to benefit the farming class in my lifetime. So I busy myself with my garden and chickens and have given up all hope of making the world any better.”

It is a heartbreaking sentiment coming from a woman who contributed so much to the populist movement, yet even Kellie’s own words might fail to capture the full scope of her impact. Luna Kellie’s goal was never to have a career in politics; still, she found widespread acclaim as a speaker, writer, and organizer. She was driven to politics by personal hardships, and even though the main cause she fought for may not have found success, she did succeed at giving a voice to the great number of people who faced problems similar to hers.

Featured image: Library of Congress

Considering History: Sophia Hayden and the Hidden Cost of American Sexism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Late last week, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren ended her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, leaving the primary without any of the ground-breakingly high number of women who had once been part of its slate of candidates. (Hawaii Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard remains in the race but has received only two delegates and has never polled above low single digits.) While Warren’s campaign and exit were both influenced by a number of factors, her departure has occasioned numerous commentaries on the continued, frustrating reality (particularly when compared to most other nations in the world) that the United States has never elected a woman to its highest political office — a reality particularly worth engaging on the occasion of Women’s History Month.

The presidency is a strikingly visible element of American society, making the historic and continued absence of women likewise quite apparent. But that absence also reflects a far wider and deeper, and yet often more difficult to spot, aspect of our collective histories: the ways in which sexism and the glass ceiling have driven so many of our most talented and impressive women out of their chosen professions, leaving our entire society profoundly diminished as a result. Few American figures and stories encapsulate that hidden cost of sexism better than the architect Sophia Hayden Bennett (1868-1953).

Hayden was born in Santiago, Chile, to a Chilean mother (Elezena Fernandez) and an American father (George Hayden), a dentist who had moved to Chile from his native Boston a few years earlier. When she was six, her parents sent her back to the Boston area by herself, to live with her grandparents in Jamaica Plain and attend school. While studying at West Roxbury High School she became interested in architecture, and she would go on to attend MIT, graduating in 1890 as one of the first two female graduates of a collegiate architecture program in American history (her classmate, Lois Lilley Howe, with whom Hayden shared a drafting room at MIT, was the second).

Despite that prestigious degree, Hayden was unable to find an apprentice position at any local architecture firms and took a job teaching mechanical drawing at the Eliot School, a vocational grammar school in Boston. But less than a year later she learned of a strikingly unique new opportunity: the chance to design the Woman’s Building, one of the planned exhibition halls for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. After extensive negotiation, women’s rights groups had convinced the exposition directors to create a Board of Lady Managers comprised entirely of women, and in February 1891 that board, headed by the socialite and activist Bertha Honoré Palmer, announced a competition for the Woman’s Building design, open only to female architects.

The competition’s $1000 prize/commission was significantly less than what was offered to male architects for the exposition’s other buildings, and so Louise Blanchard Bethune, considered the first professional female architect in America, refused to submit a concept. But Hayden did submit, and out of the 13 proposed designs it was her innovative concept, based in part on concepts from Italian Renaissance classicism, that the Board (along with Chief of Construction Daniel Burnham) selected as the winner. She traveled to Chicago to begin work on turning that design into construction plans as quickly as possible, as construction needed to begin in the summer of 1891 to be ready for the exposition’s May 1893 opening.

That hugely expedited timeline was only one of many challenges that Hayden would face over the next two years. Despite having chosen Hayden’s design, the Board of Lady Managers identified a number of perceived shortcomings and requested many changes, including the addition of an entirely new third story, which required Hayden to overhaul many other aspects as well. Moreover, Board Chair Palmer decided to take control of the building’s interior design away from Hayden entirely after the architect resisted some of the Board’s other substantial proposed changes. Hayden managed to respond to, complete, and work around such extraordinary requests within that very tight schedule and on budget to boot, and the Women’s Building was formally introduced at the exposition’s October 21, 1892, dedication ceremony. But shortly after, it was reported that Hayden suffered a possible nervous breakdown (in some reports referred to as “melancholia”) in Burnham’s office, and she was confined to a “rest home” for months in order to recover.

It’s impossible to know precisely the role that Hayden’s gender played in all those developments, although it’s certainly important to note that such medical diagnoses and conditions themselves were hugely gendered in the late 19th century (as illustrated by the long history of the illness known as “hysteria,” as well as related contexts like physician S. Weir Mitchell’s popular “rest cure” for women and the depiction of its destructive effects in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s autobiographical short story “The Yellow Wallpaper”). Moreover, many of the prominent responses to her design were overtly limited by narratives of gender, as illustrated by architect and critic Henry van Brunt’s argument (as part of a long series entitled “Architecture at the World’s Columbian Exposition”) that the building seemed “rather lyric than epic in character, and [that] it takes its proper place on the Exposition grounds with a certain modest grace of manner not inappropriate to its uses and to its authorship.”

Although Hayden was “cured” in time to leave the rest home and attend the exposition before its November 1893 closing (after which the Women’s Building, like most of the exposition’s structures, was demolished), she would as far as we know never design another building. An editorial in the journal American Architect lamented that fate while managing to reinforce sexist narratives at the same time, writing, “Miss Hayden has been victimized by her fellow-women. The unkind strain would have been the same had the work been as unwisely imposed upon a masculine beginner.” Hayden returned to the Boston area, eventually marrying local painter William Bennett in May 1900. Their wedding announcement in the Boston Daily Advertiser noted that “both are highly esteemed and respected . . . versatile as well as talented,” but again as far as we know Hayden never again publicly employed her prodigious talents, living her remaining six decades as a private person in their Winthrop, MA home.

What might American architecture, America’s cities, American society have looked like if Sophia Hayden had continued to design buildings? What would American history look like if we had elected a woman president by now (or if women had received the vote before 1920, for another example)? Such questions remain painfully hypothetical and unknowable, reflecting a collective loss that parallels the individual and personal costs of sexism so embodied by a figure like Sophia Hayden.

Featured image: The 24 female MIT students in 1888. Sophia Hayden is in the front row, far left. (MIT Museum)

How Our Grandmothers Disappeared into History

I recently googled my grandmother’s name. I wanted to know the date she died so I could better place a childhood memory. In the 21st century, embarrassingly, the internet has become the family Bible. The first hit was a link to my own book, a history of Southern motherhood. I had dedicated the book, in part, to her. My stomach gave a funny flip. I had gone looking for my grandmother and found myself — and yet my own writing was resurrecting her. This is an ouroboros of women’s history. We search for our mothers in the past and find only mirrors.

Women are notoriously hard to find in American archives. Their names keep getting folded under. You have to trace fathers and husbands to triangulate an identity. Names float down the generations on rafts of privilege: whiteness helps, as does wealth, and maleness makes everything simpler. A George Washington is a George Washington eternal. (His wife Martha was a Dandridge, then a Custis, then a Washington.) I am white, and my mother’s ancestors were of the class that kept others in bondage. Even with all their record-keeping, I can see only eight generations down the female line: Elise, Elise, Elise, Ellen, Elizabeth, Elizabeth, Mary, Ann, and then a woman identified as “Unknown.” Unknown couldn’t legally own property and had nothing to pass down except the intangibles of her voice, her scent, whatever knowledge she possessed, and, perhaps, her first name. Maybe she was named Ann too.

Names float down the generations on rafts of privilege: whiteness helps, as does wealth, and maleness makes everything simpler.

Though trained as a historian, I am now a novelist, a sequence of careers that anyone who knew me years ago could have predicted. The fictions I wrote as a youth were nearly suffocated with names. I was a budding genealogist, a self-historian, and was entranced by naming — that defining impulse that led me also to fill my mother’s grade books with made-up students. But naming is nurturing too; I wanted to rope my characters into a web of relation. When I was 12 or 13, I learned about Lydia, an ancestor on a different branch of the family who would have been about my age during the Revolutionary War. The story I started writing about her got sidetracked by a detailed map I made of her 45 cousins, but what narrative I spun was marked by my obsessions:

Father used to call me Lyd-John. It was a little joke of ours — I was the boy born with a silly girl’s name. I never used to consider myself bound by all the rules of maidenhood; the etiquette, the dress, the eating habits (Father says I eat like a horse), but as I grow up and across and sideways, I find myself uncomfortably slipping into propriety. I fear I’ve been around Mother too much.

Perhaps my fear was invisibility: not being remarked, recorded, remembered. Another of my early American grandmothers was named Desire — who could forget that? One of her grandmothers shows up on our family tree as Wife #1. Beyond that, unknowns.

As women took the names of their men, so too were many enslaved people stuck with the names of those who claimed to own them. In writing my history book, I learned of a Southern family that had maintained better records than my own. Each newborn was listed with a name, birth date, and the name of the child’s mother. No fathers at all, because the state of enslavement, since the Virginia Slave Law of 1662, was dependent on the condition of the mother. White men could gift their names to white descendants, erasing the heritable influence of white women, and simultaneously — conveniently — absent themselves from black lineages, converting their own forced offspring into property.

As the names of black babies in that Southern family were being recorded by a white hand, a white daughter (Sarah) was taken from home by her husband. Her letters to her mother (also Sarah) are one-note: “I cant help regretting that I could not spend a few more days with my ever Dear Mother before I left you Dearst and best of Mothers. Of all the tryalls that ever Crossed me that of parting from my Dear mother has been the hardest.” When the elder Sarah died in 1818, the 37 enslaved people she counted as her personal property were sold, at least five of them mothers with young children. Thirty-seven bodies amounted to $18,535 (about $350,000 today), money which went — where? To Sarah’s one surviving son, most likely: Francis, named after his father.

But white Sarah had named her daughter Sarah, who named her daughter Sarah. And on the plantation simultaneously was a black Sarah, whose daughter Moll named her first daughter Sarah. My white great-grandmother Elise named her daughter Elise, who named her daughter Elise. There is a holding onto identity — to slim power — here.

Stories can live on without names, though they’re harder to find, harder to push to the front of others’ imaginations.

How do you search for a woman in the archives if her name is only Sarah? For many African Americans — whose racial identity was determined by legal status, whose legal status derived from the mother — genealogies break off mid-tree. Even in white lineages, women dangle tenuously, like leaves. How to find a simple “Sarah” in America? Sarah who raised you, who washed you, who maybe taught you letters, and how to hide, and what parts of religion to trust? To hunt for our mothers’ names in the past is to pull back the heavy curtains of property — both being propertied and being property. Names denote possession. I’m a descendant of the South Carolina Clinkscales. So too is Jimmy Carter; so too is a black woman who checked me in at a conference several years ago. I recently saw a Clinkscales pop up in the credits of I, Tonya, and I later looked him up: a young black man from Georgia. We might be kin; we might just share a white man’s name.

Naming alone doesn’t create history, as I learned in my early attempts at historical fiction. Stories can live on without names, though they’re harder to find, harder to push to the front of others’ imaginations. So I call out the dead Sarahs when I find them, I ask the living Elises for their memories. I clutch my ancestors’ objects, which I know I’m lucky to claim. I have my great-great-great-grandmother’s fork, my great-great-grandmother’s ring, my great-grandmother’s sewing table, my grandmother’s small pink compact, the powder within still smelling strongly of her. A fork, a ring, a table, a mirror. This is the moral of naming, that what has a label is remembered. If we in turn label the unknowns, will the ghosts of our mothers begin to rise?

This article originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org).

It is also featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock