Ride ‘Em and Weep: Amusement Parks in 1945

In 1945, World War II was ending, G.I.s were returning home, and Americans were ready to put the grim times behind them and have a little fun. Enter the amusement park.

Amusement rides made their debut long before the 1940s. The first rides – merry-go-rounds — have been around since the Roman age of emperors. In the 1600s, the French improved on the idea, developing a carrousel to simulate a jousting match.

The first carrousels appeared in America in the early 1800s, and the first planned amusement park – Playland – opened in Rye, NY, in 1928.

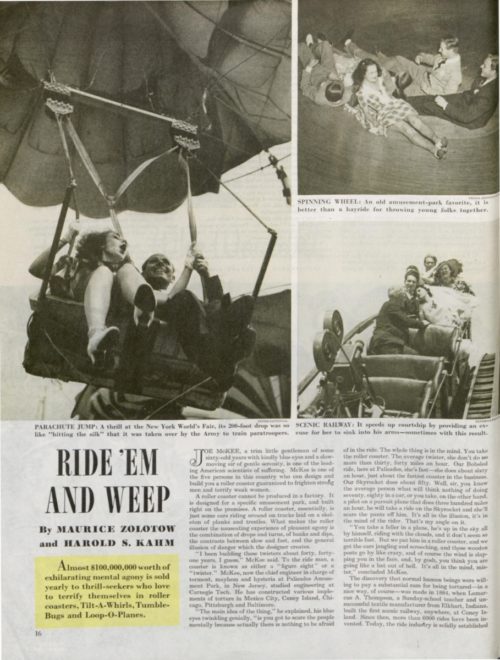

By the 1940s, amusement parks had expanded their offerings to Tilt-A-Whirls, Whips, Dodg’ems, Skooters, Loop-O-Planes, Ferris wheels, and Tumble-Bugs. It was enough of a national trend to appear in an article in the June, 9, 1945, issue of the Post, where the authors interviewed the creators of these scream machines. William Mangels, one of the largest makers of merry-go-rounds, noted that he’d tried using lions, tigers, and giraffes, but people always preferred the horses. Another manufacturer, W.E. Sullivan, owned a bridge company, but nobody bought his bridges. So he started making Ferris wheels, and sold five millions dollars’ worth.

But the real money was in the good old roller coaster – in 1945, one could ride the Thunderbolt, Skyrocket, Zephyr, Mile Sky Chaser, Cyclone, and Giant Racer. While the coasters of the 1940s didn’t nearly match the height, speed, or insane gyrations of modern coasters, they were just as terrifying – maybe even more so for being built upon clattering wooden frames.

In the 1940s, ride makers were still trying to figure out ways to make their coasters faster, scarier, and more stomach-turning. One inventor came up with the Loop-the-Loop, but it didn’t make the cut; at the time it could only move one car at a time around the vertical circle, rendering it unprofitable.

Then, as now, we can’t get enough of rides that terrorize. Why do we love them so much? A psychiatrist of the era said it allowed riders to “experience a pattern of emotions which brings him back to the ‘secure insecurity’ of childhood, and this is one of the sources of the perverse pleasure.”

Sadly, many of the parks mentioned in the article have since closed. Palisades Amusement Park, across the Hudson river on a bluff overlooking New York City, closed 1971. Luxury apartments were built in its place. Pontchartrain Beach outside of New Orleans closed down in 1983. And the Coney Island park mentioned in the article, Steeplechase Park, closed in 1964 (Coney Island is still home to two amusement parks – Luna Park and Deno’s Wonder Wheel Amusement Park).

Amusement parks of the 1940s were no doubt quaint compared to the slick, expensive, immersive parks of today. The authors couldn’t have foreseen what the theme parks would become, or that families would plan week-long vacations and spend thousands of dollars on them. The opening of Disneyland, after all, was still ten years off. But 75 years later, the thrill is still there. As one ride maker observed, “”The new generations are always growing up…and they are always discovering for themselves the same old rides, the same old thrills. No, you can’t ever change that. These rides are as old as gravity.”

Featured image: Geauga Lake Park, Geauga Lake, Ohio (Wikimedia Commons / Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers collection #77801)

Safety Second: Who Regulates Thrill Rides?

What is the price of excitement? Hundreds of millions of thrill ride attendees each year assume it’s the cost of a ticket, but some end up paying with a trip to the emergency room — or worse. Most people figure amusement rides are safe, but the safety regulations are fuzzy.

The United States boasts the tallest thrill rides in the world, and their namesakes suggest ferocity and danger: Fury, Intimidator, Lightning Rod. The appeal of amusement park rides is a feeling of peril — see the Post’s “When Science Takes You on a Ride” — but is there actually a risk?

According to the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions (IAAPA), the risk of “being seriously injured on a fixed-site ride at a U.S. amusement park is 1 in 16,000,000,” while the odds of being struck by lightning in the U.S. are 1 in 775,000.

Of course, the numbers are different for mobile rides — the ones found at carnivals and fairs. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission estimates that over 30,000 emergency-room visits in 2016 were a result of thrill ride injuries overall. A recent malfunction on a ride at the Ohio state fair that killed one teenager and injured seven others prompted Governor John Kasich to call it “the worst tragedy in the history of the fair.” Last year three girls fell at least 30 feet from a Ferris wheel car at a county fair in Tennessee, and last week a crew rescued three people from a county fair bungee ride in California.

Some mobile rides have had systemic problems, like the Zipper. In 1977, the CPSC issued a warning to consumers and filed suit against the Chance Manufacturing Co. after four separate accidents on the Zipper left four people dead and two injured. All four incidents involved the locks on the doors of the carriages. This case helped to establish the CPSC as a regulator for carnival rides despite industry claims that a thrill ride is not a “consumer product.”

In 1981, a budget bill stripped federal oversight of fixed-site rides from the CPSC in a move known as the “roller coaster loophole.” This amendment left it up to individual states to set regulatory measures for permanent amusement parks and water parks. Some states have enacted strict regulations, while others remain without any.

In Kansas, amusement parks were left to perform their own inspections until a recent law established tighter rules on reporting accidents as well as a state-sanctioned inspector. This came after Kansas Rep. Scott Schwab’s son died on a water slide at Schlitterbahn Water Park in Kansas City in 2016. The ride, called Verrukt, was the tallest water slide in the world at the time. Immediately following the accident, reporting from several news outlets revealed other riders who had expressed previous concern over the inadequate seatbelt restraints. Schwab gave an emotional speech to the Kansas House in March in support of the law that would add government regulation.

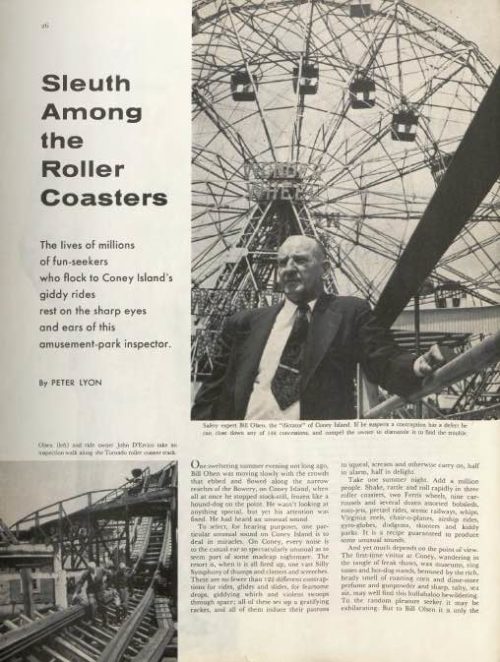

Regulation for the amusement ride industry had been left up to individual companies in the past, when there wasn’t much of an industry. Coney Island employed its own safety inspector in the 1950s, as reported in The Saturday Evening Post’s 1957 article, “Sleuth Among the Roller Coasters.” That sleuth, Bill Olsen, was a Brooklyn elevator inspector charged with issuing licenses to individual ride owners and ensuring their compliance to a safety code seemingly composed of his own whims. The author followed Olsen around the fun park as he relied on his ears to detect any glitches in the park’s 122 rides. To be fair, Olsen’s record during his tenure was laudable: “During the 17 years that he has been the inspector of Coney Island’s rides there has been no major accident and only one minor accident.”

Thrill ride safety is not so conspicuous in the modern days of gargantuan coasters, however. Permanent amusement parks are not under jurisdiction of the CPSC, and they’ve been building taller and faster thrills in recent years. The concern with roller coasters that drop passengers 400 feet at more than 120 miles per hour is less about malfunction than it is about G-force.

Massachusetts Senator Edward Markey has cited the new monster roller coasters as one reason to allow CPSC oversight at fixed-site amusement parks. A recent ABC News story quoted Markey: “Some of these rides now reach speeds of 100 miles per hour and forces greater than astronauts are trained to endure on the space shuttle.” The senator contends that data on injuries from these rides would be more centralized with CPSC oversight.

The amusement park industry is, of course, opposed to any new federal regulations. The IAAPA maintains that “a majority of the injuries occur because the guest didn’t follow posted ride safety guidelines or rode with a pre-existing medical condition.”

Whatever the future of thrill ride regulation may be, Americans do not appear to be halting trips to theme parks. Six Flags Entertainment announced a seventh year of record attendance. For less intrepid riders, technological advancement can afford thrills that rely on illusion instead of linear induction motors. Virtual reality, even in cases of malfunction, is unlikely to cause injury — other than a little nausea.

Featured image by GOLFX on Shutterstock