Why Mario Andretti Is the Greatest Race Car Driver of All Time

For more on Mario Andretti, don’t miss Post Editorial Director Steve Slon’s interview with the IndyCar legend. We also republished a June 1967 profile on the racer by John Skow, “Dueling with Slingshots at 180 MPH”.

If you want to talk about Mario Andretti, start with the number 111. It’s a powerful number on the face of it, combining the number 1 and lucky 11. It’s also the number of checkered flags Mario took in his legendary five-decade career. Few can rival his accomplishments. He could make a bad car competitive and a competitive car victorious — on any track, on any surface — including ovals, road courses, drag strips, dirt, and pavement. He won some of the greatest races in the world, including the Indianapolis 500 and the Daytona 500. He was Formula One World Champion. He was the IndyCar National Champion four times. He was a three-time winner at Sebring and won the Pikes Peak Hill Climb. He won races in sports cars, sprint cars, and stock cars.

As far as honors go, let’s just say the trophy case is full to bursting. Andretti was named Driver of the Year in three different decades (the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s), Driver of the Quarter Century (in the ’90s), and Driver of the Century in 2000. A fearsome competitor, he’s surprisingly modest about the accolades. “Well, you know,” he says, a trace of an accent betraying his immigration from Italy in 1955, “it’s the ultimate compliment to receive these honors. And I don’t say that lightly. I competed against racers I admired and drew inspiration from. So to be the one selected, I can only say, ‘Oh my God!’”

That phrase, “Oh my God!” is a frequent one. It comes up when talking about how overwhelmed he was to win a race or even to realize his youthful dream of competing in auto racing at all. It also comes up when he talks about the miracle of coming to this country at 15 and adopting it for his own, becoming an exemplar of the American Dream. But the expression never seems overused, because so many of Andretti’s experiences have an actual oh-my-God quality to them.

The future superstar of racing and his twin brother were born in Montona, Italy, in 1940. Montona, which is now part of Croatia, is about 35 miles from the city of Trieste, inland from the Adriatic Sea. Their father was self-employed and had made a decent life for the family owning and managing seven farms — mostly wheat fields and grapes.

World War II broke out around the time the twins were born. Even when the war ended, there was no peace because the borders were in dispute, as they always are following war. In 1945, Montona was ceded to communist Yugoslavia, “So our life changed dramatically,” Andretti says. “All our land was taken by the state. It was one thing for my parents to know deep down that they would never amount to anything under communist rule — and quite another to make a move. And move where? We stuck it out for three years hoping that the only world we had ever known would right itself.”

But when things hadn’t changed by 1948, the family of five, including Mario and his twin brother, Aldo, and their older sister, Anna Maria, traveled back to Italy. This was permitted as long as they didn’t take anything with them. Their first stop was a central dispersement camp in Udine. About a week later, they were transferred to a refugee camp in the medieval Tuscan town of Lucca.

For seven years, from 1948 until 1955, the Andrettis lived in the refugee camp that held 5,000 families. They shared a large room with about 25 other families, their quarters separated by blankets.

It was while living in Italy that the brothers fell in love with car racing. “In the town square, there was a parking garage,” Andretti says. “Aldo and I used to hang out there after school, and that’s actually where we learned to drive. The garage was always packed, and the cars parked in tight rows because space was such a premium. Businessmen who worked in the city would valet their cars and leave them for the day. Pretty soon, the two guys who owned the garage allowed us to park the cars. We would jump into these Lancias and Alfas and do burnouts! To this day, I’m wary of valet parking because I know what we used to do. We would practice standing starts, you know, like Formula One!”

The two guys who owned the parking garage further indulged the young racing fans by taking them to see local races like the Giro di Toscana. And one of Mario’s fondest memories is the sports car race called the Mille Miglia, a 1,000-mile lap around Italy. “One of the segments ran through the Abetone pass, near Florence. Every year, my brother and I would watch from the side of the road. Back home we would talk about nothing else for weeks. We were so jacked up.” Then in 1954 the fellows who owned the parking garage took the Andretti twins to the Italian Grand Prix in Monza. The boys were only 14, but the die was cast. Mario saw his idol, Alberto Ascari, and told himself: I’ll be back here someday.

Now all the while, their father was determined to move the family to America. It was going on seven years since they had been in the camp (for Mario and Aldo, that was age 8 to age 15). Then, all of a sudden, their visas came through and their parents gave them the news: We’re moving to America. An Uncle Tony who lived in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, said he would sponsor them, a commitment that included the guarantee of a job and a place to stay.

On the morning of June 16, 1955, the Andrettis arrived in New York Harbor on the ocean liner Conte Biancamano. “It was a beautiful morning, my sister’s 21st birthday, as we sailed under the Statue of Liberty,” Mario recalls. “The backdrop of the city looked so beautiful, colorful, with all the yellow cabs flying around. My cousin Johnny picked us up with a Plymouth station wagon.”

It was an immediate culture shock to be sure, more so for Mario’s dad than for the kids. “Along the way, we stopped for lunch at one of those typical chrome diners. We didn’t know what to order, and we didn’t speak much English, so Johnny ordered for us, some hamburgers and things. Now, my dad had a very sophisticated palate — he said the hamburgers tasted like cardboard. But Johnny ordered a milkshake for us kids. I’d never tasted anything like that before! Oh my God, I loved the milkshake!”

As fate would have it, their new home was not far from the Pennsylvania state fairgrounds. And inside the fairgrounds, lo and behold, was a race track. “We arrived in Nazareth on a Thursday,” recalls Andretti. “But on Sunday, after church, we were at Uncle Tony’s house, and about a mile away there are these bright lights, and all of a sudden in the background, we hear this big roar. I looked at Aldo and he looked at me and we just booked!”

They followed the noise until they reached the fairgrounds. “Looking through the fence, we see these brute-looking cars, not very sophisticated like grand prix cars we had seen in Italy. But they were fast as hell!”

They resolved to get into a race there. But how? “When you have that desire,” says Andretti, “it supersedes reason. You just go out there and somehow you get it done. We just wanted to do it so bad. Now, there are three ways to get a car: Steal it (against our principles), buy it (we didn’t have any money), or build it. We were in manic pursuit to build a car.”

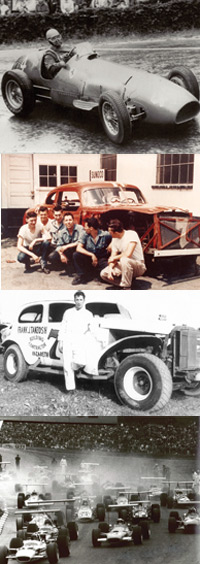

They worked part-time at a gas station to put some money together, and by 1959, they had built a racing machine from a 1948 Hudson Hornet Sportsman stock car. Andretti credits his science-minded buddy Charlie Mitch for helping them think big about the project. Most of the other drivers on this local circuit were driving rebuilt Fords and Chevys, modified with big tires and big engines. Charlie said, “Instead of building cars like everyone else’s, let’s do something special.”

Charlie and the brothers got in touch with a NASCAR team driving Hudsons that had developed an ideal “setup” for the car — a program for tuning, wheelbase, suspension, and so forth. The boys bought the professional setup and built their car to those specs. Their car was different, and so was their appearance. “Everybody looked very scruffy, wearing jeans and T-shirts. But Aldo and I got ourselves racing uniforms from Salas Sports in Italy, one white and one blue, with all kinds of zippers so they looked official. We had the two guys from the parking garage send them to us.”

To the other competitors at this dirt track in rural Pennsylvania, they might as well have been from Mars. “People asked, ‘Where are you guys from?’ And we said, ‘Oh, we’re from Italy. We used to race there,’ which was, of course, total B.S.”

Also total B.S. were their driver’s licenses. By the time their car was ready to race, they were still two years shy of 21, which was then the minimum age for racing. They managed to get help changing their birth dates on the licenses — something that would almost derail their careers later on.

But now, they were ready to go.

Only one of them could drive in that first race. “Aldo and I had to toss a coin. He won the toss. I was actually glad,” Mario admits. “I was very nervous. I knew if he did well, I’d have a shot to do well at the next race. I was perfectly happy to watch.”

Because the boys had no track record, the promoters started Aldo last in the heat race, a 16-car trial with 10 laps. “He went out there and won the heat!” Andretti recalls. “Oh my God! I could not believe my eyes.”

The winner of the heat was paid $25 immediately.

“Then, they started him last in the feature race, and he won that too!”

The feature race paid $125. And the following week, it was Mario’s turn to drive and he repeated the same trick, winning both his heat and the feature. Between them, the boys had won $300 in two weeks’ time. Which was nice because they had run up about $1,000 in debt building their car.

The brothers became a formidable team, taking turns racing the Hudson on the minor league circuit. Then tragedy struck. Near the end of the 1959 season, Aldo was fighting for the lead in a race when he flipped over the guardrail, flinging the car end over end. He was taken to the hospital with a fractured skull. The doctors weren’t sure he’d make it, and a priest was called to administer last rites.

Their father was furious because he didn’t know the boys were racing. He had absolutely forbidden it because he felt it was too dangerous, so the boys had concealed their car-building project, working on the Hudson in a neighbor’s garage.

Aldo was in a coma for two long, scary months. When he finally awoke, his first words to Mario were, “I’m glad you were the one who had to face the old man!”

A year later, their new car was ready to go, and by then, their dad had come around a little bit. “He started realizing we were going to do this no matter what, so he might as well give in and join the party,” recalls Mario. “The way he did it was funny. After a race, he’d say to Aldo, ‘How did Mario do?’ and then he’d ask me, ‘How did Aldo do?’ For a while, he never asked directly.”

The boys kept racing, and they kept winning. Mario won 20 races in the sportsman stock car class in those first two seasons. Then, in 1961, the twins crossed the magic threshold of 21 years of age. “The reason we got away with fudging our age for so long was that these were local tracks, not sanctioned races,” Andretti explains. “But by the time I was 21, I didn’t want to be 23! In fact, I had a hell of a time getting back to 21!”

Mario’s first victory of consequence came the following year, on March 3, 1962, a 100-lap feature TQ Midget race at Teaneck, New Jersey. Then, on Labor Day in 1963, he won three midget features on the same day — one at Flemington, New Jersey, and two at Hatfield, Pennsylvania.

Midway through 1964, Mario finally was in a situation to gain national attention. His opportunity came when one of the drivers for an elite professional team was injured and Mario took over his seat. “That’s how it often worked,” Andretti says matter-of-factly. “You almost waited for a driver to get hurt (or worse) to get that chance.”

So for the second half of that season, Mario found himself racing against the best drivers in the world, driving the fastest cars of the day, on what is now known as the IndyCar circuit. It was the kind of challenge he’d dreamed of since he was a boy. “Finally I was able to compete against drivers like A.J. Foyt, Roger McCluskey, and so many others,” he recalls. “That first year, I had some good finishes, one third-place finish, and I won a 100-lap race at Salem, Indiana.”

Another personal triumph also occurred in 1964: Their dad finally came to watch Mario race. It was the first time he saw his son in action. It was also one of the first times Andretti raced against the elite of his sport. “I ended up finishing 11th, which I thought was okay,” Andretti says. “And I expected him to be very encouraging and say, ‘Hey you did really well against all these top dogs.’ Instead, he was disappointed. ‘I thought you were winning races!’”

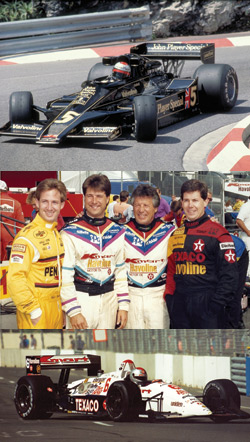

In 1966, after 11 years in America, the Andrettis applied for U.S. citizenship. “We felt we were solidly established and this was going to be our home for the rest of our lives, and we were thankful for that,” Mario says. In the years that followed, Mario’s achievements would become legendary: The world watched as he won the top NASCAR race (the Daytona 500) in 1967, the top IndyCar race (the Indianapolis 500) in 1969, and the Formula One World Championship in 1978 — an unprecedented trifecta. To this day, no other race car driver has ever won all three titles.

The sad part about this story is that it didn’t work out for Aldo. He had a second accident in 1969, after which he was hospitalized for several weeks and suffered such severe facial injuries that he and Mario no longer looked like identical twins. It was the end of racing for Aldo. “He had worked just as hard as me,” Mario says. “And he had wanted it just as bad. It’s hard for me to put into words how tough this was.”

In the ’80s, Mario teamed up with his son Michael, establishing the first-ever father-son front row in qualifying for the 1986 Phoenix IndyCar event. In the 1990s, with his two sons (Michael and Jeff) and his nephew (John Andretti), Mario made another first as the four family members competed in the same IndyCar race at Milwaukee, June 3, 1990. The following year, the four Andrettis raced against one another for the first time in the Indianapolis 500. Jeff was voted Rookie of the Year, joining Mario (1965), Michael (1984), and years later Michael’s son Marco (2006) as the only four members of the same family to win the award.

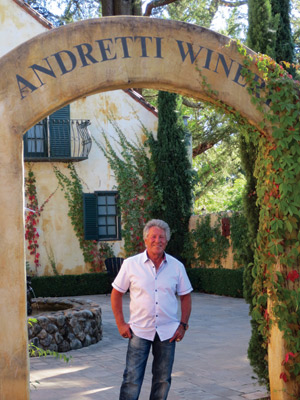

In 1993, he won at Phoenix, becoming the oldest driver (at age 53) to win an IndyCar race. Mario retired from full-time racing in 1994, but he still works nearly every day, doing high-speed testing for Honda and making appearances for such national brands as Firestone, Bridgestone, Honda, and GoDaddy. You’ll find his name on a winery in Napa Valley and a petroleum business in California. And he’s still tearing up the track in the Honda-powered two-seat IndyCar with Lady Gaga, Donald Trump, and other VIPs as his passengers. “My wife says, ‘When are you going to grow up?’” he says with a laugh.

It’s been a great career and a charmed life, but not without personal tragedy. As mentioned, his two sons, Jeff and Michael, followed him into auto racing. While Michael became successful as a driver and now as owner of the Andretti Autosport race team, featuring his own son Marco as a driver, Jeff suffered a devastating crash in Indianapolis that ended his career, nearly costing him his legs.

While Mario himself never experienced a serious injury, he did wreck his fair share of race cars. One crash that still haunts him came during a Formula One race in Belgium in 1977. As he told the online racing magazine The Player’s Tribune, “It began to rain just before the start of the race. I had won two of the last three races and I felt like I was in a good early position to distance myself in points in the world championship standings. I was on pole in my Lotus, side by side with John Watson in his Alfa Romeo. It was a standing start. At the green light, I got too much wheel spin on the wet track and he beat me off the line — one of the very few times I got beat off the line. As I approached Turn 3 — still pissed that he beat me off the line — I thought, I’m gonna go get him.”

But when he tried to make a move, he bumped Watson, and they both spun out and were out of the race. The experience was instructive: “You can’t win a race on the first lap. But you can lose it,” he says today, adding, “you wish you had that one back.”

Considering the dangers of auto racing, did Andretti ever have qualms about putting not just himself on the line, but his brother, his sons, his nephew, his grandson? “No question, it’s a dangerous sport,” Mario says. “Did we dwell on it? No. We know of the hazard, but if you’re going to race, you have to accept that fact. You have to be willing to take the risk to reach your goals.”

What is the distinctive quality that makes him one of the greatest drivers of all time? “I have a clear thought about that,” Andretti says. “I loved driving. I wanted to do it so bad, oh my God, you have no idea! It goes back to the days when I was watching my idol Ascari on the track. I thought to myself, I would give anything, a limb, to be able to do that someday! And when it started happening, I felt so blessed and so fortunate. My passion and desire for the sport is unequaled anywhere. I still do love it. It all goes back to the fact that I had to overcome not just the obstacles, but I had to try to impress even my own father. I had to show him, ‘Dad, you have to realize how much I really want this.’”

Mario Andretti, who didn’t arrive in this country until age 15, today is as patriotic an American as you’ll find anywhere. “I represent a shining example of the American Dream, an immigrant who came to this country and this country gave me the opportunity to satisfy the ultimate dream,” he says. “When you look back at the tragedy of World War II, the tragedy of having to leave your home, the tragedy of having to live for seven years in a refugee camp — oh God, the living conditions — but all of that negative turned into a beautiful positive for us.”

Only in America?

Andretti answers: “I don’t think it could have happened anywhere else.”

Also read our June 3, 1967, profile of Mario Andretti from the Post‘s archive.

Steven Slon is the editorial director for The Saturday Evening Post. He wrote about Alaska in the March/April issue. Follow him on Twitter @steveslon.

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.