News of the Week: Black Friday, White Christmas, and the Many Joys of the Moist Maker

At Some Stores, It Actually Started Last Night

I don’t believe in Black Friday. I mean, I believe it exists. I’m not crazy, and I’ve seen all of the “pre-Black Friday sale” commercials. I just don’t think anyone should participate. Why stand in line with 1,000 other people just to save 40 percent on a toaster? You can always wait to buy the items (or buy them earlier than today), and there’s this thing called the internet where you can get all of the things you’re going to buy today (like, ahem, a new subscription to the Post), often at the same discount or even more.

If you do feel like shopping today, here are some tips for getting the best deals with the least amount of hassle. And don’t forget that this Monday is Cyber Monday, the day when many sites have big deals. By the way, when did the word cyber come back in vogue? I thought that went out with information superhighway.

If you’re feeling like a rebel, please note that today is also Buy Nothing Day. But I’d bet few people are going to celebrate it.

Christmas TV

Christmas season has begun, which means that Christmas TV season has also begun.

This amazing site has a really great list of all the Christmas specials and holiday movies that are coming up from now until New Year’s Day. So if you’re into movies like White Christmas and It’s a Wonderful Life or animated specials like Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer and A Charlie Brown Christmas, you’ll find it on the list. It even lists Christmas-themed episodes of TV shows, everything from ER and Friends to Father Knows Best and The Equalizer. You can even find out where you can watch classic Christmas specials from Bing Crosby, Perry Como, and Judy Garland.

I’ve looked at the schedule, and I’ve also done a search on some TV listing sites, and I don’t see Miracle on 34th Street at all. Seriously? I guess that’s why God invented DVDs.

Superman for Sale

I wasn’t a big comic book collector when I was a kid. I had some — I was into Superman, Batman, and Spider-Man — but I never thought about them enough to actually “collect” them. I had some in my attic, and once in a while I wonder if I ever owned anything that would go for a lot of money today. I never had the one where Superman made his first appearance though. I’d remember that.

That’s Action Comics #1, and it’s a rare, expensive thing, especially if it’s in fine to mint condition. One of them is going up for auction at Profiles in History in Los Angeles. It sold for 10 cents in 1938 and it could go for up to $1.2 million. It would make a great Christmas gift for the superhero fan in your family.

Maybe I should go back to my old house and check the attic. I’m sure the current occupants won’t mind.

Your NPR Name

There’s another meme (pronounced “meem”) going around the web — one of those things that passes from one person to another that everyone contributes to. This one is your National Public Radio name. Here’s how you do it: it’s a name that was popular in the 1880s–90s plus something that is being made obsolete by either global warming or the internet.

Mine is Clarence Brick and Mortar Stores.

RIP David Cassidy, Malcolm Young, Della Reese, and Mel Tillis

Four stars of the music world died this week.

David Cassidy was the lead singer of the Partridge Family on the 70s sitcom of the same name. He had one of the great voices in pop history, on songs like “I Think I Love You,” “Echo Valley 2-6809,” “I’ll Meet You Halfway,” and “Point Me In The Direction of Albuquerque,” and the group of studio musicians that played on the songs were first-rate. Cassidy died Tuesday at the age of 67.

Malcolm Young was a guitarist and founding member of the rock group AC/DC, known for such songs as “Highway to Hell,” “You Shook Me All Night Long,” and “Back in Black.” He died Saturday at the age of 64.

Della Reese started as a singer in churches and later with Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Miles Davis, and many others. She then became an actress and appeared in many movies and TV shows, including a starring role on Touched by an Angel. Reese died Sunday at the age of 86.

Mel Tillis was known for his stutter, which didn’t affect his singing of country songs like “Southern Rain” and “Good Woman Blues.” He was also a songwriter, penning songs for Kenny Rogers, George Strait, and many others. He died Sunday at the age of 85.

The Best and Worst of the Week

A new feature of Week in Review, where I pick two things that particularly stood out the past week, one good and one bad.

The Best: I have a confession to make. I haven’t watched 60 Minutes that much in the past several years. Not that it isn’t a great show — it’s still the best newsmagazine on television — but the main reason I tuned in, the main reason a lot of people tuned in, was for Andy Rooney’s essay at the end. The show isn’t the same without him. So imagine the happy surprise fans had when they tuned into last Sunday’s episode and saw Rooney at the end of the show again! They replayed his essay on Thanksgiving, and I really hope it’s just the first of many returns that Rooney will make to the show.

The Worst: This also involves Rooney. Charlie Rose had Jeff Fager, longtime producer of 60 Minutes, on his PBS show. He was on for the entire hour, plus 15 minutes of the next episode, and they talked about every single contributor to 60 Minutes over the past 50 years. They talked about Mike Wallace and Morley Safer and Lesley Stahl, even Anderson Cooper and Oprah Winfrey and David Martin. Guess who they didn’t mention at all, not even in a quick, passing reference?

Andy Rooney.

Can you believe that? I was stunned. It was like watching a documentary on the Boston Red Sox and they mention all the players except Ted Williams. Rooney was arguably the most beloved person on the show for many decades, and he doesn’t get a mention? Very odd.

To make up for it, here’s an interview we did with Rooney in 1984.

This Week in History

First Appearance of Tweety Bird (November 21, 1942)

No, not that tweety bird, I’m talking about the little yellow bird from Warner Brothers cartoons. He (and yes, it is a he) made his first appearance in 1942’s “A Tale of Two Kitties.”

President Kennedy Assassinated (November 22, 1963)

This week, more of the previously unreleased files on the assassination were made public by the National Archives. The director of our own archive, Jeff Nilsson, has a nice retrospective on the many articles we’ve had on Kennedy over the years.

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Eavesdropping on Sis (November 19, 1949)

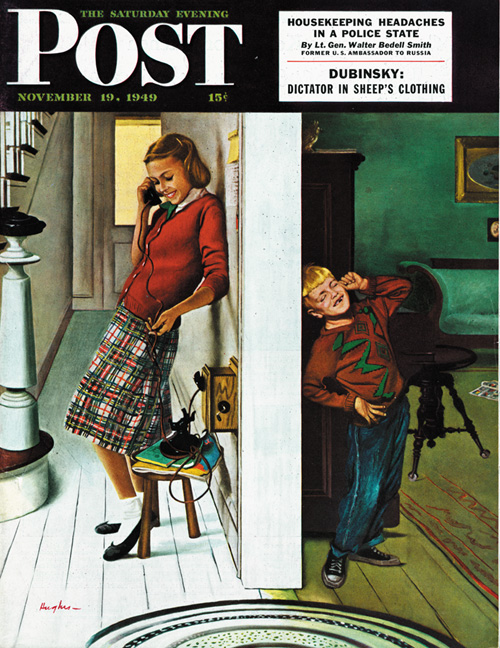

Eavesdropping on Sis

November 19, 1949

This scene by George Hughes is probably alien to many young people. Just one phone in the house, and it’s attached to the wall by a wire? That’s barbaric! But older people remember. I recall fondly the big, heavy black rotary phone we had in the corner of the kitchen. If you wanted to talk to your friends (or that girl you liked from school) on the phone, you had to do it there, in a high-traffic area. Now kids have their own phones and parents don’t know what’s going on.

This cover is actually one of three “eavesdropping” covers that Hughes did for the Post.

What to Do with Thanksgiving Leftovers

You probably have turkey and other foods in your fridge right now. My leftovers plan is pretty simple: I make sandwiches. I don’t make turkey soup or turkey casserole; I just heat up the turkey and stuffing and make big sandwiches. Also: reheated mashed potatoes taste funny to me.

Beyond sandwiches, here’s a recipe for Turkey Pumpkin Chili you might want to try. You get the two big tastes of the season in one bowl. Here’s a Next Day Turkey Primavera, and for something a little different, maybe these Thanksgiving Nachos.

Okay, if you’re just making sandwiches, let’s once again take a cue from one of the shows on that Christmas TV Schedule site: Friends. It’s The Moist Maker, the turkey sandwich Monica made for her brother, Ross, who flipped out when someone at work ate it.

The secret is the third piece of gravy-soaked bread in the middle.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Christmas in Rockefeller Center (November 29)

Last week I told you about the tree being delivered, and now you can see the official lighting and listen to the sounds of Gwen Stefani, Brett Eldredge, Leslie Odom Jr., Jennifer Nettles, The Tenors, and Pentatonix. The shows airs on NBC at 8 p.m. Eastern and is hosted by Matt Lauer, Savannah Guthrie, Hoda Kotb, and Al Roker.

Write a Friend Month Begins (December 1)

Personally, I think we should celebrate Write a Friend Month every month of the year. Here’s what you do: Get out some nice stationery — or go out and buy some if you don’t have any already — grab a pen, and take the time to write an actual letter. Not a quick note, but a real, long letter, the kind people used to write P.T. (pre-texting). Don’t use any smiley faces or web abbreviations like LOL. Put it in an envelope, seal it, place a stamp in the corner, and take it to a mailbox.

Oh, and don’t email or text the person to tell them that you’re mailing it to them. Let it be a surprise.

From Our Archives: Sixty Minutes With Andy Rooney

To honor Andy Rooney, who passed away on November 4, we are reprinting this interview that first appeared in the March 1984 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

From a cluttered corner at CBS headquarters in New York, Andy Rooney sips day-old coffee from a plastic Harris Tweed mug and grumbles about his “overnight” success. It took 64 years to get here, and like money, it’s “a pain in the tail,” he insists. It cramps his style when he meanders through hardware stores, is a source of embarrassment down at the lunch counter and sometimes causes him to miss the bus to work.

“A writer should be sitting over in the corner watching the dance and not be out there dancing,” he muses. “I’m not too keen about my recent well-knownness; I don’t handle it very well. If somebody comes up to me on the street and says, ‘Hey, I like your stuff,’ well, I can’t hate that. But it never stops there. Pretty soon he wants to be my best friend. I tend to be rude to people like that.”

He comes by his crustiness naturally. He’s one of the last of the trench-coat journalists who covered the Big War—World War II—for the print media. He was Sergeant Rooney then, a veteran of several bombing missions and the Stars and Stripes reporter who landed on Normandy Beach four days after D-Day to document the invasion of France. Hardly a suave TV personality in the Dan Rather-Peter Jennings tradition, he looks more like a preppy leprechaun with John L. Lewis eyebrows and a fondness for growling at strangers. His bite has earned him a reputation as CBS News’ resident curmudgeon, but his bark is more fun than fact. During a recent 60-minute interview with the SatEve Post, he was downright hospitable as he shared insights, the day-old coffee and all the comforts of his infamously cluttered nest.

“Sit down, sit down,” he urged, beckoning to a black vinyl chair that had a suspiciously gimpy leg. I sat, and the leg gave way and sent me flailing toward a floor strewn with size 8’/2 EEE shoes, maps destined someday for a wall and a family portrait of somebody else’s family.

“I’ve got to fix this chair,” he muttered resolutely from a squat position as he examined the now splintered leg.

He means it. An avowed do-it-himselfer, he prefers to fend for himself and refutes the notion that celebrity status translates into clout. Forget the limousines, the house on Long Island, the cadre of secretaries poised to take a letter. He commutes daily from Connecticut via train and bus, pecks out his own correspondence on an Underwood typewriter three years older than he is, builds furniture and bakes bread. He and wife Marguerite still live in the same house where their four children grew up.

“We paid $29,500 for it, and I have no intention of moving out,” he says.

His home away from home—the modest cubicle in the CBS building on West 57th Street—has a decidedly less permanent air to it. A hodgepodge of books are stacked every which way on shelves behind his desk and beg to be arranged. A gold-colored statuette, representing some lofty award for past accomplishments, reclines on its backside atop the books and close to a large box labeled simply “Jane’s stuff.” Pictures, yet to be hung, lean against a sway-backed couch.

“Just move in?” I ask.

He nods affirmatively and adds: “Ten years ago.”

The decor is eclectic—a functional jumble of treasures that smacks of the owner. Lampshades tilt uniformly off-center, mounds of paper threaten to obscure the desk; an LBJ-Lady Bird commemorative plate is tacked to the wall, and a grouping of black-and-white Hollywood publicity pictures invite visitors to test their knowledge of film trivia. But it’s no contest. Rooney explains the “celebrities” are actually Columbia Studio’s rejects— starlets who didn’t make it big in show biz.

To this unlikely haven comes a network-news crew each week to tape “A Few Minutes with Andy Rooney,” the wildly successful p.s. to television’s top-ranked show, “60 Minutes.” The humorous commentary has earned two Emmys since becoming a permanent feature of the show in September 1978. And that’s not bad for a low-budget operation.

“I don’t move a thing,” says Rooney. “It’s been a strange union problem because they say we’ve got to have a set decorator. But we don’t have a set. We shoot right in here. See that microphone? It runs into Bob Forte’s editing room. Believe me, we don’t fuss with this thing. Sometimes the cameraman will say there are too many white papers on the desk—causes a glare—so I toss some yellow paper on top and say, ‘Is this better?’ Sure, we make concessions; but it’s very homemade. Remarkably homemade.”

For the show Rooney generally sits at his desk in front of the jammed bookshelves and to the right of LB J and Lady Bird. He peers over horn-rimmed half-glasses and addresses issues close to home, wherever home may be. Viewers seldom notice the “set” since his words command their full attention. He’s the folksy philosopher who un derstands little things. He manages to say what others only feel, and this ability has established a kinship with “60 Minutes” aficionados. Often sage, sometimes silly, always succinct, his messages zing in on truths common to everyone. He can evoke chuckles when he sounds off on designer jeans and tears when he comments on the pain of growing old. The most common topics become special under his treatment, and his way with words has swelled the ranks of Rooney followers to such proportions that a brief Sunday-evening fix of his humor just isn’t enough. Fans have turned in increasing numbers to his three-times-weekly newspaper column—now syndicated in 324 publications—and to his books, the most recent, And More by Andy Rooney, a bona fide best seller of 1 million copies in hardback and 2 million in paperback. Still, it’s television exposure that has brought about the star status and the high visibility he finds so disagreeable.

“I’m irritated that some people think I only got successful when I did ’60 Minutes.’ I was doing things I was proud of 20 years ago,” he grumbles. “Fame is an overrated quality. I don’t think nearly as highly of well-known people as I did before I was one. And money. It’s a lot like fame. Overrated. Oh, I enjoy having $150 in my pocket instead of $32 or $19, but that’s all. Money is a pain in the tail. I’m no good with it—I don’t know what to do with it.”

Unbelievable? Not so, says Mr. Rooney, although he concedes perhaps once fame wasn’t quite as distasteful as it is today.

“I did a piece once called ‘Mr. Rooney Goes to Washington’ about seven or eight years ago,” he recalls. “It was a good piece—an hour long. I remember the next morning a guy came up to me at the bus stop and said he had seen the show and had really liked it. I was pleased. That was about the last time I was pleased.”

His impatience with fame is caused partly by his inability to understand why he deserves it. He refutes all claims that he’s better than Buchwald, more wry than Rogers or in the same genre as Menken, Twain or Thurber.

“That’s baloney. Buchwald is funnier than I am; Menken and Twain were so much smarter. No, I reject that. I’ll never last as they have,” he protests. “What I do is easy; I can’t believe it’s special or different. But it’s a delight—the most fun I have. I enjoy making it clear to people that we are so basically the same for all our differences. I can’t get over the fact that there is a common thread that runs through all of us. We share so many characteristics. It makes the world a little less lonely place to be, and I like that feeling.”

His talent for tugging at the common thread comes from his ability to totally tune into his subject. Heightened perception, he calls it, and it’s available on command. He explains that when he has to write a column or commentary, he merely turns up his tuner and grabs hold of something he might otherwise overlook. He looks at the subject head-on and dissects it. When the writing is done, the antennae retract and he reverts to being a tourist.

If this perception is a natural gift, it’s been carefully honed by the down-home Hoosier, Borge was veddy sophisticated, Levinson was folksy Jewish and Godfrey was, well, just Godfrey.

“Writing for those guys was a terrific lesson. I’ve probably borrowed something from all of them. They were tough; there was a lot of arguing. It was highly competitive getting your stuff into the monologues,” he admits. “There’s no writing more precise than the kind that has to provoke laughter. You know you’re hitting people when they laugh. It has to pay off, and the positioning of words is so important in triggering it.”

Joke writing led to collaboration with Harry Reasoner on several CBS News specials. Rooney provided the words and Reasoner added the voice. Not until he joined the Public Broadcasting Service’s “The Great American Dream Machine” did Rooney actually go on camera himself. Afterward, he was contacted by an advertising-agency talent scout who wanted him to narrate a headache-remedy commercial. That told him a lot about his voice, he quips.

He returned to CBS, this time to both write and narrate such on-the-air efforts as “Mr. Rooney Goes to Dinner” (he added 14 pounds by the end of the assignment), “Mr. Rooney Goes to Work” and an occasional political commentary. Viewers related to his less-than-perfect physique (a pudgy 5′ 9″), his appearance (rumpled) and his voice (restrained whine). When the dueling duo of Shana Alexander and James Kilpatrick went on vacation from “60 Minutes” in the summer of 1978, Rooney was tabbed as the replacement. The temporary assignment became permanent the next year, leaving him little time for the longer, more in-depth stories he had always enjoyed.

“I miss reporting a lot,” he admits. “But the fact is, I have become more valuable to myself and everyone else by doing more writing and less reporting.”

He stops, props his 8 1/2 EEEs up on his desk and engages in a little pipe dream: “You know what I’d really love to do?” he asks. “I’d like to throw myself into writing and reporting for Charlie Kuralt. I’d like to just give him my stuff. For one thing, he does things better than almost anyone in the business. Then I could slip back into anonymity. I’m telling you, it wouldn’t bother meat all.”

He loves the language and the agony of arranging and rearranging words, the shaking-out of a piece of writing until nothing remains except the emotion that propels it forward and makes it reach out and touch the reader or listener. The creative process is tough, causing him to rant, wring his hands and pace as his assistant Jane Bradford reads, edits and passes judgment.

“Jane checks everything I do. If I spell my own name she checks and makes sure it’s all right. She drives me crazy, but she’s very good. I make a lot of mistakes, and she keeps me from making a fool of myself. The other day I was desperate to get my column done. I finally finished it and gave it to her to read, and she said it just wasn’t good enough. God, I knew she was right. I had to sit down and do it over.”

Even a bit of writing scrutinized and passed into print is not immune to Rooney’s self-criticism.

“I look at things I wrote ten years ago and think, ‘My gosh, how could I have done that?’ Then I look at things I wrote last year and think, ‘How could I have done thafl When am I going to grow up?’ ”

He claims he has a particularly difficult time ending things well, and that holds true not only for his writing but for his other passion, woodworking, as well. Both require patience—not his long suit.

“Actually, it’s a real shortcoming of mine. I guess I’ve gotten better at it in my column, but I’m a big woodworker and I’ve never been able to finish furniture very well, either. I’m interested in the idea of forming a table or a chair or a cabinet, but then I don’t have the patience to finish it the way I should.”

So immersed is he with his vocation—writing—and his avocation— woodworking—that he often describes one in terms of the other. A particularly tough script is called “a real cabinetmakers’s job of writing.” His profession underwrites his passion, and his only splurge since he became a TV celebrity has been a $2,700 power saw. He used it to build, from scratch, a free-standing writing room at the family vacation compound in upstate New York. Weekends from May to October are spent at the New York “cottage,” which is a sprawling, white colonial estate with two outbuildings—one for writing and another for woodworking. From the first he churns out columns and scripts; from the second come tables and sideboards.

“My kids have a lot of my furniture in their houses. Sometimes I make it faster than anyone wants it. I’m not a natural woodworker, but I use good wood and have pretty good ideas. Boy, you talk about being self-taught. When I built my writing room I couldn’t get over how many mistakes I made. I fell off a ladder at one point, and that stopped construction for about a month.”

In many respects he’s self-taught in his writing craft, too. His ideas are good, his instincts are on target and if the words feel right to him, chances are he’s succeeded in building a thought people can relate to. He takes care in choosing his topics and is particularly wary of subjects that might amuse the cosmopolitan folks of New York but elude residents of rural America. He frets that a recent piece on the irritations of air travel only touched a small segment of his audience. He rejects the suggestion by a CBS coworker to use telephone answering machines as the object of an upcoming diatribe. “How many viewers have answering machines?” he asks.

He stays in touch with his audience by living the normal life he champions. He avoids posh parties and the social set in an effort to protect his averageness. At a time when TV programming is determined by ratings and demographic studies, he refuses to be influenced by scientific data. Don’t burden him with the number of households tuned to CBS at 7 p.m. on Sundays. Don’t tell him which geographic areas of the country appreciate his humor most or which pockets of the population prefer a Lawrence Welk rerun.

“That’s the road to death,” he says of market studies. “It’s like trying to understand flight by dissecting the entrails of a robin. I would never study the numbers. A good pilot knows how it feels to fly right.”

And after more than 40 years in the business, he’s flying higher than ever. He’s earned his stripes with a flight plan that has proved to be impeccable: From his cluttered vantage point, he looks out at the dancers and simply wings it.