Cartoons: Horsing Around

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Reginald Hider

October 6, 1951

Irwin Caplan

August 16, 1952

Goldstein

July 31, 1954

Chon Day

June 9, 1951

Gallagher

April 24, 1954

Frank O’Neal

April 19, 1955

Shirvanian

October 13, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Protecting Animals from Beasts

There was a time in this country when cruelty was hard to see.

Everyone knew what it was. They recognized it in the attacks of Native Americans on settlers, but they had a hard time seeing it among themselves. Life was hard. Cruelty, many assumed, was necessary — unpleasant, perhaps, but expedient.

But cruelty and brutality didn’t sit well with the ideas of liberty. The patriots of the new country were rightly suspicious of any “rule by force.” In the years following the Revolution, Americans started to recognize how cruelty was often used for domination — of the poor, the sick, the insane, of children, and women. By the mid-1800s, they even began to see cruelty in the system of slavery — or, rather, they started to acknowledge what they’d already known.

In time, the widespread practices of mistreating animals also became clear. The Post helped raise public awareness though numerous articles of the 1860s.

Here, for example, they denounce the cosmetic mutilation of dogs:

“Sir Edwin Landseer, one of the judges at the dog show in London, England, endeavored to exclude all dogs that had been mutilated by ear-cropping or otherwise. The principal reason… is, that the cropping of ears is most and hurtful of the dog… All dogs, more or less, require to be protected from sand and earth by overlapping ears; but especially do terriers, literally “earth dogs,” the species which, of all others, is most persecuted by cropping.

“The only excuse that can be set up for the system is a delusive one. It is said that fighting dogs fare better with their ears cropped, and the exigencies of fighting dogs have set the fashion of all others… Leave the dog his ear, and the assailant’s grasp of the sensitive gland [within] is impeded by the folds of the ear, and rendered much more feeble. Thus, even to the fighting dog, the long ear is a positive defense.” [Dec, 6, 1862]

Curiously the reporter accepted commercial dogfighting as an inevitability. (Dog fighting has been illegal in all states since 1976. The last state to outlaw cockfighting did so in 2008.)

The Post pointed out potential abuse of farm animals:

“Kindness must be constantly exercised toward milch cows, and we might add towards all domestic animals. Very often young cows are restless or irritable, especially during the operation of milking, but whatever the cause gentleness is the only treatment that should be allowed — violence or even harshness never. There are many causes after recent calving that may produce inquietude, but no other remedy will be effectual. A young animal never forgets ill treatment, and a recurrence of similar circumstances will remind the cow of former punishment.” [Sep. 2, 1871]

“Stabling of every description is an evil. It is impossible a stable should be so built that it will allow the animal one half the freedom he enjoys when loose out of doors… The fact is, our modern stables throw the stress upon the back sinews or flexor tendons, and thus prepare many an animal for injury… Nor is this all: the stall is perfectly at variance with the habits of the horse: he is evidently gregarious, [living] among crowds of his fellow-creatures; the stall dooms him to solitude, and the groom sits behind to see he does not put his nose over the division, only to look at a comrade. In many stables the stall is so small that the horse cannot turn around; he can lie down perfectly at ease in very few.” [Nov. 22, 1856]

“In offering Prizes for animals in agricultural meetings, distinction should be made between those smothered in fat, by which the framework is totally concealed, and those whose proportions are visible, though well covered with wholesome meat… It may be amusement — there is no accounting for taste — to watch an unfortunate quadruped daily increase in size, till he becomes unable to stand without assistance of his attendant, who is obliged to cram him by hand. This may almost be said to be cruelty to animals for no good purpose. [my italics]… The first thing to be considered in regard to stock is not who can, regardless of cost and trouble, bring before a wondering public a live mass of grease, which, after a gleam of astonishment has passed away, fills the mind with a sickening sensation and compassion for the sufferings of the brute – [quoted from the London’ Gardeners’ Chronicle, Feb. 7, 1857]

The Post even raised concerns about the abuse of animals in the name of science:

“In the veterinary colleges of France, especially in the great establishments of Alfort, and Lyons,… the pupils are regularly instructed in surgery by cutting up living horses… This fiendish lesson is given regularly twice a week; when the doomed horse is cast, and is then subjected to all sorts of surgical operations… Steel, and fingers guided by stony hearts, invade the poor animal at all points; these operations on the same horse lasting from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon, unless, indeed, the poor animal escapes from the diabolical torments inflicted upon him, by dying in the meantime… Vivisection is condemned everywhere but in France, as absolutely unnecessary to the successful cultivation of the veterinary art.” [Nov. 17, 1860]

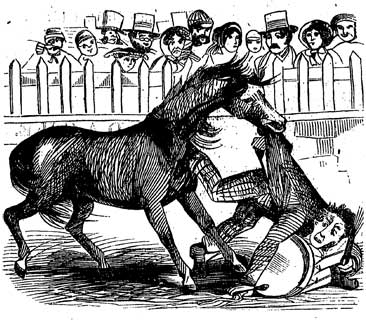

Americans in these years lived closely with horses. They relied heavily on them for transportation and farm work. The practices of beating, starving, whipping, and maiming horses was more than just barbaric, it was ingratitude.

“We would suggest to the society for the prevention of cruelty to animals — and an excellent and greatly needed society it is — to take a glance occasionally at the manner in which horses, monkeys, etc., are treated in our circuses. The whip, we are included to think, is much too freely resorted to by those who have the training of these co-called brute performers… Forepaugh’s Menagerie and Circus is now on its travels — an excellent Menagerie and a very poor Circus — but what pleasure can be derived by any intelligent and tender-hearted audience, from the displays of the leading horse… To see an animal naturally of a very fine intelligence, with its high spirits all broken down by the whip, and shivering and trembling over the difficult feats required of it, so far from giving pleasure, almost makes a sympathetic observer sick. [April 11, 1868]

The Post’s editors frequently praised the work of John Rarey, who had developed a method for horse training that avoided all beating and punishment.

“The horse, according to Rarey, is happier in finding his master than he could be without him, provided the action of his master be kind, gentle, and adapted to the needs and instincts of the horse. Make him feel that you have him utterly in your power and that your power is kindly, and the horse is your happy and affectionate servant henceforth.” [Feb. 16, 1861]

In praising Rarey, the Post was voicing one of its strongest arguments against cruelty to animals: that cruelty is never contained. The idea of using pain and fear, even on dumb animals, pollutes a democratic society. “Cruelty to an animal touches every human man and woman precisely as cruelty to a human being does — the only difference being one of degree and not of kind.”

“The force and benefit of Mr. Rarey’s precepts and example in bringing about a more humane and sensible mode of dealing with horses, can hardly be over-estimated. And in rescuing horses from foolish brutality, he is aiding in overturning the general reign of brutality and ignorance in the world. If horses can be managed by calm force used intelligently in a spirit of kindness, why not children, why not men? We therefore enroll the name of Rarey not only among the benefactors of Horses, but also among the benefactors of Mankind. [Feb. 16, 1861]