North Country Girl: Chapter 52 — The Whipped Cream Wars

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

James and I were back in Chicago where I had found an agency that had agreed to take me on as the World’s Most Unlikely Model. I had stopped trying to style my hair after one disastrous experiment with hot rollers when I was reduced to having to use scissors to cut a curler out from a tangle of hair, I never understood what foundation was for, and I topped off at 5’3”. But according to Silver, the astrologer husband of Ann Geddes, who owned the eponymous modeling agency, my horoscope showed that I would be a great success.

The morning after Ann and Silver elevated me to Professional Model status, I left James holding his head in his hands and took the El to a lonely weird industrial area that lay in the shadow of the gigantic Merchandise Mart. Ann Geddes had sent me here in search of a photographer who would take photos of me for free — photos I could use to create a modeling composite that would land me actual work.

I found a dirty business card reading “Frank Wojtkiewicz, Photographer” stuck in a mailbox slot on one of the more crumbling buildings. There was no doorbell and no one around. I pushed open the rusty steel door and rode a creaky freight elevator up to the third floor. I banged on another steel door, which was thrown open by a big Polish bear of a guy, wearing a torn, grubby t-shirt and holding a can of beer.

Frank grunted, “A model, huh?” and led me into the first loft I had ever seen. In the front huddled a battered fridge (which held nothing but beer and film), a filthy sofa, and a rumpled mattress, glaringly lit by tall metal paned windows overlooking the Chicago River. In the back was Frank’s studio and darkroom.

No, I had no photos to show him, I was hoping that he could take some. Yes, I would like a beer (at 9:30 in the morning). Yes, I had modeling experience (well, I did have one modeling job, by accident). Would I do nude photos? I hesitated and answered truthfully that I didn’t know. I couldn’t think of a reason not to; after all a senior citizen from Des Plaines and a med student and his wife had all seen me naked.

Frank was gruff, unwashed on the outside, marshmallow heart on the inside, a wannabe Screbneski who lived on beer (I never saw him consume solid food), and who had no paying work at all. I don’t know how he stayed alive. But he had lots of time on his hands to shoot pretty girls who came knocking at his door.

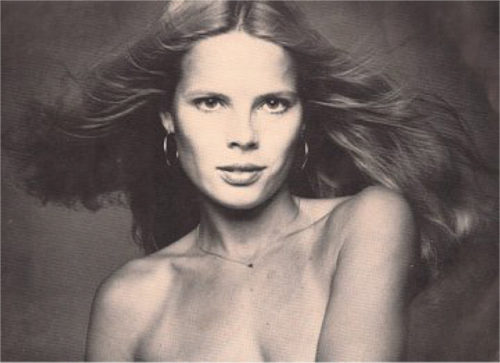

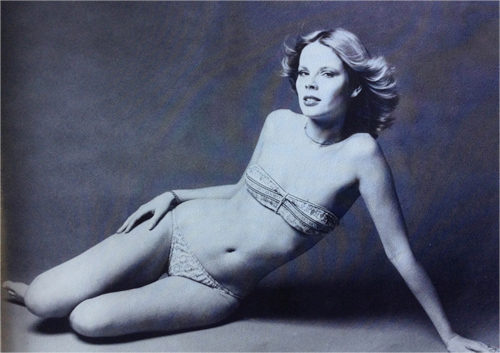

Frank set me up under a huge white umbrella and then bustled about fiddling with a bunch of silver reflectors and a gigantic floor fan before shooting off a roll of film. He took a beer and the film into his darkroom and emerged with photos of me that were so flattering it was like looking at someone else.

Frank shot me like a sexy angel, my hair glowing behind me, my skin gleaming like a South Sea pearl, cheekbones I didn’t know I had sculpting my face.

“Wow,” I said, and Frank swaggered a little. It seemed churlish not to take off my shirt. Frank shot another role of film, and somehow these photos were even better. I used one of these photos, cropped below the collarbone that only Frank could find, as my head shot for years, arms crossed demurely over my chest, hair blowing back, wearing nothing but the dainty star necklace James had bought me in Acapulco.

I asked Frank if he could shoot the other photos I needed, to show off my range, my versatility: me holding a coffee cup or steno pad or tennis racket. “Bring beer,” he agreed. These photos were not as inspired, but they did demonstrate that I could stand in front of a camera and smile. I now had professional photos that had only cost me a few six packs. And I had made a new friend whose dirty loft provided a refuge from James’s days of fury.

Within a week, I had 1,000 black and white composites (which I paid for) imprinted with my name and “Represented by Ann Geddes Agency.” I was officially a model.

Which meant exactly nothing. Models from Ford and Wilhelmina were always cast for the most lucrative jobs, television commercials, and ads in national magazines. As the Number Two girl at the Number Three model agency, I was rarely sent off to auditions or go-sees. I sadly let go of my former belief that I would be starring in commercials once or twice a week. But I couldn’t sit and wait for the phone to ring. I needed money and I needed to get away from James and his foul desperation.

I wore out my shoes and my feet criss-crossing Chicago, dropping off my composite at every photographer on Ann’s list in the hopes that he (there was not a single female photographer) would be shooting something that required a small cute girl. I took the El north and south and tried to figure out Chicago’s arcane bus routes, but mostly I walked. I was not going to waste money on cabs.

Every evening I mapped out a route of photo studios and businesses and ad agencies, seeing how many I could hit on the least amount of carfare. My Chicago had previously consisted of a four-block square, extending from our Oak Street apartment to Faces disco to the backgammon club, with occasional trips to Marshall Fields downtown for Clinique lipsticks and Frango mints, or back in the good old days of a year ago, north to Greektown for moussaka.

Now I had to venture forth all over that sprawling city, from suburban Evanston, where I looked longingly at the ivied and brick campus of Northwestern, to close enough to the stockyards to smell them, from the skyscrapers of Miracle Mile to the scarred and scary South Side, previously terra incognita to me.

There was actually a lot of modeling work in Chicago. Sears and Spiegel were there; their tombstone catalogs required scores of models, posing in everything from bikinis to tool sheds. Popeil, famous for the Pocket Fisherman, churned out new low-budget commercials for dubious inventions every week. There were conventions and fashion shows that needed models who could talk or walk. Chicago had major ad agencies, like Leo Burnett and J. Walter Thompson, who very occasionally had to shoot a commercial there instead of LA or New York. There were smaller shops who cast models in trade ads for surgical or restaurant or hair salon supplies (I posed in scrubs and white paper booties, wearing a hair net, and brandishing a blow dryer). And of course there was the gaping maw of Playboy, which chewed girls up by the dozen.

Ann told me, “The more you work the more you work,” and it was true. Before I had gotten to the end of Ann’s list, a photographer cast me in an ad for Diet 7-Up, a shot of the lower half of my face behind a bubbling glass of clear soda, because I knocked on his door the day before, wearing a slash of crimson lipstick. That ad helped me land my second commercial, for the local McDonald’s franchises: I took bite after bite of an endless supply of slightly chilled Filets O Fishes, until the director got the take where the sandwich looked really, really good.

As my portfolio and demo reel filled up, I got more and more bookings, although I never made as much money modeling as I had waitressing at Pracna. I even got to walk the runway once, modeling petite-size wedding dresses, which inoculated me against ever wanting such a thing. All the gowns ended in huge, flowing trains of slippery white or ivory or eggshell satin; it felt like I was towing a small car. At the end of the runway I had to stop and beam like a real bride into the blinding lights, then execute an elegant turn, somehow without stepping on my own train, falling off the runway or colliding into the model behind me.

There were some jobs I should not have taken: greedy for my day rate ($250!) I let my hair be cut in a goofy Dorothy Hamill wedge for a beauty school instructional film, which put me hors de combat till it grew out.

Tri-State Honda hired me to throw out the first ball at the White Sox’s Comiskey Park, after I lied twice: I claimed that I knew how to ride a motorcycle and that I owned a floor-length white dress. I bought the cheapest white polyester gown I could find; my plan was to wear the dress to the ball game, with the tags carefully tucked in, and then return it to the store the next day and get my $50 back.

The nice man who delivered the Honda motorcycle to Comiskey Park gave me a quick lesson, slapped me on the butt, yelled “You’ve got it girlie!” and sent me off across the field to the pitcher’s mound. I managed to not dump the motorcycle or run over any White Sox, and actually threw the ball in the direction of home plate. But my white dress didn’t fare as well: there were greasy black oil stains all over the skirt.

Not only was I out $50 on a dress I could never wear again, Tri-State Honda didn’t pay up. The Ann Geddes Agency was not very good at bill collecting.

“I sent them an invoice.”

“Ann, can you send them another?”

“I will, after 30 days.”

Thirty days later.

“Tri-State Honda still hasn’t paid? Ann, please call them!”

“I’ll call after 30 days.”

Seething, I took my anger and frustration and a six-pack of Budweiser to Frank’s loft.

“It’s not fair!’ I cried. “And Ann isn’t helping. Honda is this big company, with all these motorcycles, and they’re taking advantage of me!” I struck my best Little Nell pose. “It’s not about the money, it’s the principle!’

“Oh, it’s about the money,” said Frank. His jaundiced take was that Ann didn’t want to piss anybody off. They were the number three agency in Chicago, and didn’t want a reputation for hounding clients over what was $10 for them. If I wanted my money, I had to get it myself. Frank had an idea; we smoked a joint of very good weed and he told me what to do.

I put on that oil-besmirched dress and went back to Tri-State Honda’s offices armed with several cans of Reddi-Whip. I told the befuddled receptionist that I was the Tri-State Honda White Sox girl and they owed me $100. If I did not get paid immediately, I was going to enjoy some Reddi-Whip, and in the process would most likely get whipped cream on the reception area’s couch and carpet. I assured her that it was very hard to get the smell of soured milk out of fabric. I sat on the couch, removed the red cap, and tilted the nozzle towards my mouth.

Frank was certain this would work, as he had once convinced a would-be model to be photographed wearing nothing but whipped cream and ended up having to toss out his sofa; I guess the stink of old dairy overwhelmed the ever-presence aroma of spilled beer in his loft.

“Can’t they arrest me?” I worried. “Probably not for Reddi-Whip,” said Frank.

The receptionist picked up the phone and the man who had hired me rushed out. I adjusted the nozzle so it pointed away from my mouth and towards the couch. “I’ll get your check,” he yelled.

Unfortunately, that $100 check was made out to the Ann Geddes Agency, leaving me $90 minus the dress and my El fare to and from Comiskey Park.

Frank was right. It was about the money. James’s good days were getting farther and farther apart. Even in those rare times when he was feeling flush again, it was hollow, as if he were acting the part of the old, confident James, the man of the world, successful investor and drug smuggler, the gambler who beat all the odds. I needed money: I had to bulk up my escape fund.

North Country Girl: Chapter 51 — Big Pink and the Invisible Man

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

James and I were in his hated hometown of Winnipeg. He had been summoned there by Elena, the daughter he had deserted years ago. As a family reunion it was a disaster; James showed no desire to spend any quality time with his chubby, homely daughter, who was more introverted and tongue-tied at 22 then I had been at 15.

Having completed his obligatory visit with Elena, James rooted out his best friend from high school, Robert, whom he had heard was doing well financially, but not exactly through legal means. Luckily for James, his pal was not locked up in the hoosegow; he was currently out on bail waiting for his next court appearance.

I felt right at home as we drove through Winnipeg to Robert’s house; his neighborhood was almost identical to the middle-class one I grew up in: big red brick houses on spacious, carefully maintained lots shaded by tall pines and paper-barked birch trees. We pulled up to one of these stately homes. A pretty blonde woman invited us in with a tight, brittle smile, introduced herself as Robert’s wife, and led us into the living room where Robert was waiting for us.

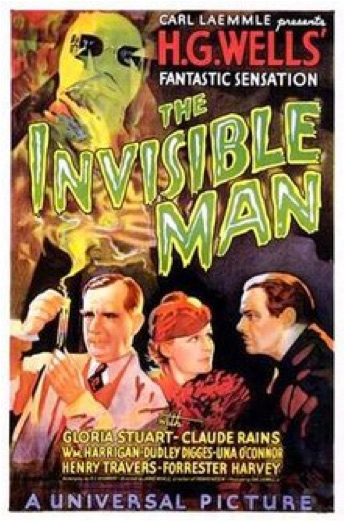

Robert’s head and hands were completely swathed in white bandages; he looked like Claude Rains in The Invisible Man. Where his face was supposed to be there were four holes poked out for eyes, nose, and mouth; his hands were oversized, slightly grimy gauze mittens. The charge he was facing was arson for profit. Robert may have been a successful criminal, but he had obviously completely screwed up this last job.

Robert’s nervous blonde wife brought out a round of Seagrams and Seven-Ups, my alkie grandfather’s tipple of choice but not mine; the rich, spicy, evocative smell of the whisky made me feel that I was seven years old.

Robert took his highball through a bendy straw, squeezing his glass between his stiff bandaged hands like a raccoon. James never asked “How’re ya feeling?” or “Oh boy, I bet that stung,” or made any reference to the fact that we were having a conversation with a man who didn’t have a face. Unlike sitting with someone who has a cast on their arm or leg, there was no humorous recounting of how Robert came to have these injuries. My own face twisted into a rictus of a smile as I tried to get through the inevitable small talk: where I was from, how I liked Winnipeg, how long the drive from Chicago had taken. I was relieved when the conversation turned to anecdotes of boyhood hijinks and whatever-happened-to’s, although I couldn’t seem to relax my face.

After they had exhausted the boring gossip about their old schoolmates, Robert said, “Hey, why don’t we all go up to my house on the lake for a few days?” I did not want to look at this talking mummy for another second, but James had already accepted, probably delighted to be out of the reach of his daughter.

In Minnesota if you had a place on the lake it was a homey cabin, with appliances from the 1940s, one or two bunkbeds in every room, musty furniture, a deck of cards with “two of clubs” scribbled on a joker, tangled fishing gear, and either electricity or indoor plumping, but never both. That was what I had pictured in my mind as we drove through the forest surrounding Lake of the Woods, catching glimpses of the shining silver water between trees. It all seemed so welcoming: the almost black firs contrasting with the gleam of white birch, the hand-painted signs posted at each turnoff with the owners’ names or the corny names of their cabins — “Dunmovin”, “The Oar House,” “Dock Holiday” — were all as familiar to me as breathing. I almost forgot that riding in the passenger seat in the car in front of us was a man with no face.

James followed that car when it turned at one of those signs, a white board with “In the Pink” neatly painted on but wanting a bit of touching up. James’s El Dorado bumped down a narrow dirt track towards the lake where we found not the rustic cabin I had expected but a sprawling modern white brick ranch. We walked into an immense living room with three sides of floor-to-ceiling windows that held all shades of sky and lake blue. Along the shore, the dark green forest was as perfectly reflected as if the water were a mirror. Next to one set of windows were twelve chairs surrounding a lengthy dining table. To the left I could see into a spacious, sleek kitchen. Robert had already told us, “Plenty of room! We’ve got four bedrooms, each with its own bath!”

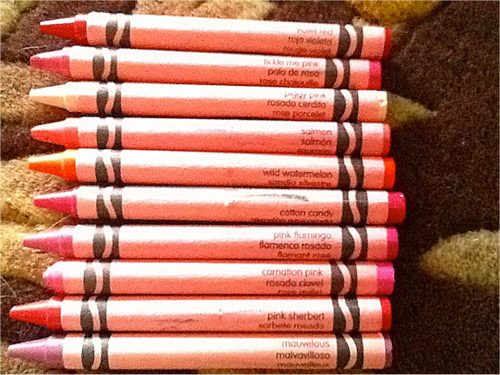

There was only one thing wrong. Everything inside the house was pink. Not just any old pink, but the exact shade of a carnation pink Crayola crayon. The sofa, the rug, the paint on the walls. The bathtubs and sinks. All the modern appliances in the kitchen. That big dining table and all the chairs.

Robert, raising his voice to be heard through his mask of bandages, showed us around, the proud owner of all that pinkness. “You wouldn’t believe the deal I got!” he boasted. When the woman who had owned and proudly decorated the house had died, there had been no other offers, and the heirs couldn’t wait to get that pink elephant off their hands.

It was like being in a brain, or an intestine, all that throbbing pink. As I soaked in the pink tub later that evening, I tried to imagine different scenarios for this obsession, but failed to come up with a likely story, as it was obviously just madness.

Not only was everything pink, everything was really nice. That tub was huge, the hot water inexhaustible. You sunk so deep and comfortably into the pink couches, all you wanted to do was sip a cocktail and gaze out the picture window at the lake. The wooden dining table and chairs were heavy and substantial, all painted and shellacked so they shone like a manicured nail. Where could you even go to buy a pink Whirlpool dishwasher? I wondered.

“You wanna see something funny?” Robert asked and led us down to the lake. There, at the end of the dock, deep in the water, under the flashing pike and drifting waterweeds, was a pink refrigerator. A salmon pink refrigerator. The wrong shade of pink. When it was delivered to the house, Mrs. Pink had freaked out and made the delivery men dump it in the lake. The big two-door refrigerator that was currently purring away in the kitchen perfectly matched the stove and the walls and the cabinets and everything else in the pink house.

“Some house,” said James. “How long have you had it?” Robert bought the house three years ago and hadn’t changed a thing. He didn’t see anything wrong with the interior, everything was first class, custom made, top of the line. So what if it was pink?

During the day I spent as much time as possible down at the dock reading or swimming or gazing out at the lake, trying not to think about James losing his fortune and his mind, his unhappy twice-rejected daughter, the bandaged arsonist with third degree burns, or the crazy house looming behind me. I lingered by the water till the loons started their plangent calls, the signal for swarms of enormous mosquitoes to descend and drive all humans inside, where three of us dined off pink plates at the huge table, Robert alternating between highballs and a disgusting looking liquid food sucked up through a straw.

James never mentioned his daughter Elena, and I certainly was not going to bring her up. He was restless as a chained wolf at that lake house; the Winnipeg Free Press did not carry even yesterday’s NYSE reports, and his requests for a New York or even a Chicago paper were met everywhere with disbelief: why would you want a newspaper from somewhere else? There was no TV at the lake house, Robert apologized, no reception out there in the north woods. James, not a lover of country life under the best of circumstances, cut our visit short. We said goodbye to that ranch house of insanity. James went to shake hands with our host, slapped him on the back instead, and we drove back to Chicago.

The news waiting for James was especially bleak. Highline shares were tumbling faster than ever. James spent the day yelling at the TV, trying to get his broker — who he now was convinced had intentionally dumped that piece of shit stock on him — on the phone, or staring into space.

I needed my own money and had a harebrained idea of how to earn it. I was going to be a model. I had already made one commercial and earned $100, why couldn’t I do two or three commercials a week?

I didn’t have a copy of my Mexico commercial. I didn’t have any professional photos. And I topped off at 5’3”. When I showed up at the Ford Modeling Agency the receptionist gazed several inches above my head, where my face was supposed to be, then showed me the door. Ditto at Wilhelmina.

In the Chicago Yellow Pages I found a small ad for the Ann Geddes Modeling Agency, which turned out to be a waiting room with three chairs, an unoccupied receptionist’s desk, and a tiny private office where Ann Geddes, a former model herself, was waiting for me, along with her husband Silver, who was a stockier, grayer version of James, and who, true to his name, wore massive Navajo silver rings and bracelets and a silver hoop in one ear.

“When’s your birthday?” Ann asked.

“Oh, I’m twenty-one.”

“No, the date and the year and if you know it, the time.”

Having gotten that settled, I started babbling about my Mexico tourism commercial (leaving out that I had been the emergency replacement) and my acting experience in high school (leaving out that the experience consisted of three lines in “You Can’t Take It With You” and the co-star role in a student-directed one-act play).

Ann Geddes was ethereally gorgeous, with long, rich red hair and milky skin unmarred by a single freckle. Her beauty was not intimidating. She was as warm and friendly as an older sister; it was easy for me to rattle on like an idiot. Silver, who had been scribbling on a pad the whole time, interrupted my life story: “I’ve got it!” He was an astrologer; while I was trying to talk my way into being a model, he was casting my horoscope. He announced that despite my shortcomings, the stars were aligned and the Geddes Agency would be happy to represent me, their take ten percent of everything I earned.

This did not mean I would have steady work or a regular income. The star of the Ann Geddes Agency was another small blonde, who was a lot prettier than I was and had several commercials under her belt that she actually had copies of. When the call came in for a model to pose next to a refrigerator or power tool to make it look bigger, she was sent. I was the backup blonde.

I did not discover my second banana status until later. At the moment I was thrilled: I was officially a model. Ann blithely handed me a contract to sign and a Xeroxed contact list of every photographer in Chicago, from the newest Chicago Art School graduate to Screbneski. It was up to me to call on all of them, trolling for modeling work.

But before I could do that, I needed a composite, an eight by eleven calling card with a pretty head shot on the front and photos showing a range of commercial personas (young mom, career girl, sportswoman) on the back to leave with the photographers. Ann took a red pen and scrawled a circle around one name on her list.

“Go see Frank Wojtkiewicz first. He might take composite photos of you for free,” she said, her face as smooth and blank as a china plate.