Considering History: Anti-Semitism and Jewish American Activism

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Today Jews around the world celebrate Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement and the end of the High Holidays for 2018. Here in the United States, the holiday period has seen continuations of two distinct but interconnected trends: troubling instances of anti-Semitism, from the chants of “Jews will not replace us” at the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville to the staggering upswing in anti-Semitic incidents on college campuses; and striking moments of Jewish American activism, as with the Rosh Hashanah sermon delivered by Stephen Miller’s childhood rabbi (Neil Comess-Daniels) in which the religious leader calls out Miller’s ideas and policies as “completely antithetical to everything I know about Judaism, Jewish law, and Jewish values.”

Each of these moments has a great deal to tell us about both the Jewish American experience specifically and American politics and society more broadly in 2018. But they also connect to longstanding and under-remembered American histories of both anti-Semitism and Jewish American activism, two threads that emerged with particular clarity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

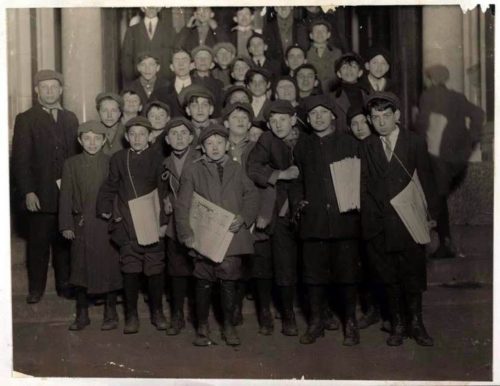

As my colleague Michael Hoberman traces in his book New Israel/New England: Jews and Puritans in Early America, Jewish Americans have been an influential community since the nation’s earliest post-contact origins. But it was the final decades of the 19th century and opening ones of the 20th that the Jewish American community truly exploded in size, thanks in particular to waves of immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe. Between 1880 and 1925 more than 2.8 million Jews immigrated to the United States, many fleeing anti-Semitic attitudes and violence in Europe. By the turn of the century these immigrants had turned communities such as New York City’s Lower East Side into some of the largest Jewish neighborhoods in the world.

As those Jewish American communities became more sizeable and prominent, so too did instances and trends of American anti-Semitism become more widespread. Leading voices in the nascent Populist movement frequently blamed Jewish “financiers” such as the Rothschilds for the era’s increasing ills of inequality and stratification, culminating in a scandal during the 1896 presidential campaign when sitting President Grover Cleveland was revealed to have sold bonds to a so-called banking “syndicate.” Founded just two years earlier, the xenophobic Immigration Restriction League focused many of its attacks on new Jewish arrivals, describing them for example as “beaten men from beaten races, representing the world failures in the struggle for existence.” These trends continued into the early 20th century and contributed significantly to the 1921 and 1924 Quota Acts, the nation’s first overarching immigration laws and ones that severely limited arrivals from Eastern and Southern Europe.

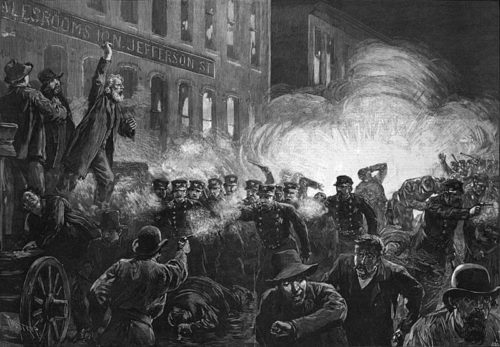

Late 19th century anti-Semitism was also deeply intertwined with collective fears of “anarchists,” labor movement organizers, and other radical figures and influences in American society. Descriptions of the eight radical journalists and anarchists arrested and tried for the May 1886 Haymarket Square bombing, for example, consistently emphasized their “foreign” and “alien” identities and perspectives. This collective prejudice added one more chilling layer to comments like this one, in a New York Times editorial on the case: “In the early stages of an acute outbreak of anarchy a Gatling gun, or if the case be severe, two, is the sovereign remedy. Later on hemp, in judicious doses, has an admirable effect in preventing the spread of the disease.” And indeed, despite the trial’s farcical qualities all eight defendants were convicted, with seven sentenced to hang (three were eventually pardoned but four others were hung).

Jewish Americans did play a key role in the early labor movement and other influential activist efforts. Some of the earliest and most prominent national labor leaders were Jewish American, including Samuel Gompers (a Sephardic Jew who had immigrated to the U.S. from England during the Civil War and became the first leader of the American Federation of Labor after its December 1886 founding) and Daniel DeLeon (an immigrant from Curaçao who became a leading figure in the groundbreaking Socialist Labor Party). More radical but just as influential was Emma Goldman, who immigrated from Russia to New York City in 1885 at the age of 16 and went on to become one of the turn of the century’s most famous activists, organizers, and writers (and also an open opponent of organized religion, making clear that there were many distinct threads in this Jewish American community).

Abraham Cahan extended Jewish American activism into the realms of journalism. Cahan was a towering turn of the century figure who deserves a far more central place in our collective memories. Cahan immigrated from Lithuania to New York’s Lower East Side in 1882 at the age of 22, fleeing a wave of anti-Semitic pogroms after the assassination of Russia’s Czar Alexander II. He quickly became active in labor and socialist movements, and in 1897 founded and began editing a weekly socialist newspaper, The Jewish Daily Forward. Named after a prominent British Social Democratic paper, the Forward (or Forverts) was published entirely in Yiddish, wedding its portrayals of Jewish American identity and community to its radical politics in clear and defining ways.

Although those politics were never absent from the Forward’s pages, Cahan made clear that the paper, the first American periodical published in Yiddish, had a broader role to play in the Jewish American community as well. The paper, he wrote, must “interest itself in the things that the masses are interested in when they aren’t preoccupied with the daily struggle for bread.” As a result he made sure to include sections on literature and culture, family and relationships, and, most famously, the advice section the “Bintel Brief” (or “bundle of letters”). In this column, Cahan himself answered reader letters on virtually every topic under the sun, including many relating directly to the multi-cultural experiences of Jewish American arrivals, families, and communities.

Cahan brought those same multi-layered interests and subjects to his literary career. Works like the 1898 short story “A Sweatshop Romance” depict the worlds of work and labor activism in fictionalized but still radical and political ways, linking audience sympathies for the story’s working class immigrant protagonists to their implicit support for labor movement concerns and efforts. But in his socially and psychologically realistic novels, especially his masterpiece The Rise of David Levinsky (1917), Cahan broadens his scope to depict many different themes and stages within the immigrant and Jewish American stories, while also linking them to shared subjects such as the American Dream, “rags to riches” ideals and realities, and more.

Indeed, what Cahan’s writings ultimately reveal is just how fundamentally American Jewish American experiences, communities, and activism are — a point that, now as then, offers a vital counter to anti-Semitic fears and hostilities.