The Splendor of Ruins

The built landscape is often how we relate visually to history. We visit archaeological sites, monuments, churches, temples, mosques, museums, forts, castles, and buildings of state. We speak of the pleasure and splendor of ruins — but how often does an architect contemplate what their creation will look like when it falls into decay? Will it still have a tangible presence? It is time going backward, returning to the beginning and exposing the bones of the structure. Archaeological sites have a form and presence never anticipated by the builders; in their altered state, we are embraced in a backward-gazing dream.

For many sites, the façade is everything. Builders were aware of light and shadow and how the interplay of the two would change throughout the day. The setting can be just as important and seductive. This would be important regardless of whether the building was religious, monumental, utilitarian, or residential.

While ruins remind us how much we have forgotten, they also give us license to dream.

Architecture is often used to make religious and cultural statements. For example, Bayon, at Angkor Thom, in Cambodia, is a state temple, a complex monument that uses face towers to create stone mountains of ascending peaks, and below are two bas-relief galleries with delicately carved historical, religious, and mythological subjects sweeping across the walls. Dancing Apsarases — spirits of the clouds and waters — are incised on pillars.

In Europe, the façades of cathedrals have saints, clerics, and angels floating above our heads, and the interior is a manmade space meant to encompass the heavens and earth, with soaring ceilings and rich imagery and decoration. They invite the congregation to worship and pray. Everyone has access to God. The altarpiece is an artistic testament to God’s power and glory and the focus of the richest display of wealth: paintings, gold leaf, carvings, and elaborate niches. Windows let in light, sometimes through stained glass, which adds a kaleidoscope of rainbow colors dancing on the floor and walls as the sun moves. It is light, mysterious, and holy.

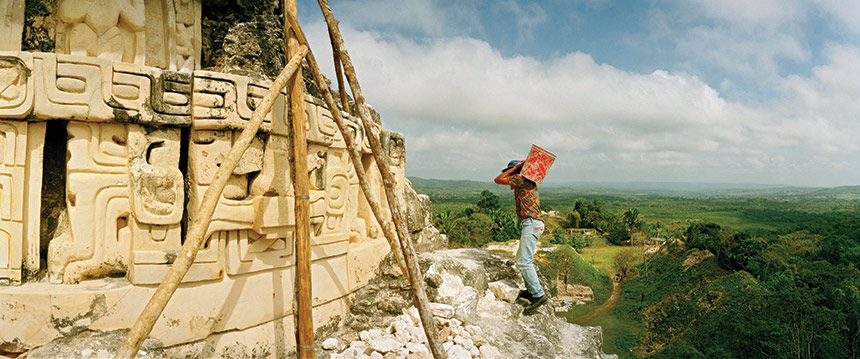

In the Americas, the Maya wrote their history on the outside of their buildings. Like any culture that believes the earth is alive, they used objects as symbols for the natural world. Their pyramids were mountains, and the doorways of their temples were the mouths of those mountains — cave entrances. Their Classic Period was noted for elite architecture, propagandistic monuments, and flamboyant theater-state rituals where epicenters of Maya sites were constructed as stage settings for religious spectacles, demonstrating the political and spiritual power of the rulers.

Humanity’s early impact on the landscape is found in the megalithic sites of Europe. Standing stones, stone circles, and cairns date to the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age. People have probably been anthropomorphizing the stones since soon after they were erected — brooding, pensive figures — maybe even witches or faeries in the woods or open moor. The builders of the Neolithic burial chamber at Pentre Ifan in Wales would never have intended it to be viewed as it is today — a large and elegant capstone balanced delicately on the tips of upright stones. They covered it with a mound of earth 130 feet long, traces of which still remain, but thousands of years of wind and rain have exposed the very essence of its design, revealing a monument of lyrical grace, equal to or surpassing modern sculpture.

An archaeological zone is referred to as a “dig” because we literally have to shovel through centuries of detritus to uncover the buildings to discover the site. There might only be the most teasing of hints, but often nothing left on the surface to tell us what will lie beneath. In the tropics we have archaeology under the canopy, mature hardwood forests crowning what once were palaces and pyramids, their roots, over time, inexorably crumbling masonry walls and breaking lintels in two.

We can see fragments of this happening today even where we live. The weeds that spring from the smallest of crevices; a sidewalk broken by a tree root, its outline traced by the bulges and cracks of the concrete; a vacant yard turned feral by neglect or foreclosure. Leaves and weeds accumulate, break down, and the mulch becomes soil. More weeds, bushes, and trees take root in the soil that collects on rooftops, inside vacant buildings, along abandoned tracks. An animal builds its nest, a bird drops a seed, and each and every thing adds its part — a reminder that, even in a city, we live in nature, even if that nature is a product of human influence. People and their towns and cities might hold nature in abeyance, by differing degrees, but it is always a part of our world, and once a city goes into decline or is abandoned, the natural world takes over.

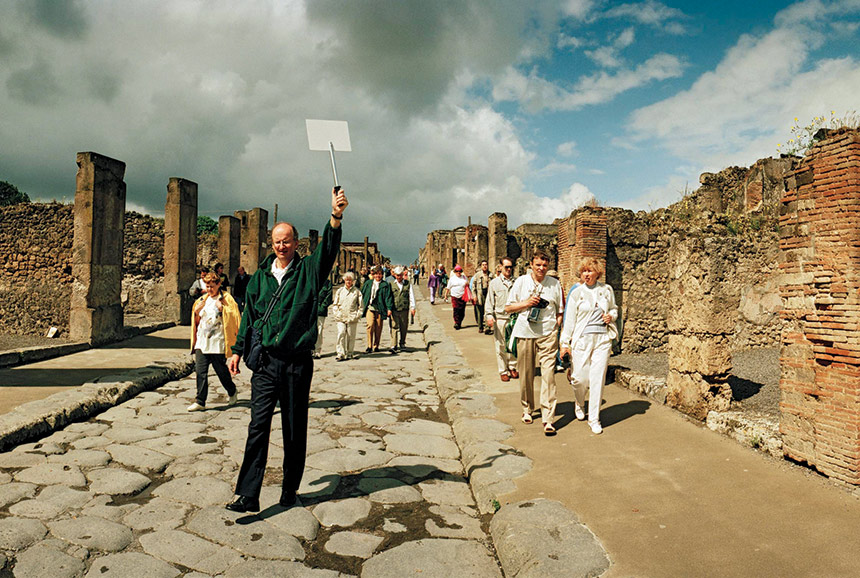

Ruins provide us an enigma to study and try to decipher. We walk around trying to see the overall picture, meanwhile looking for the details that will inform our thoughts, and we are free to come up with our own hypotheses. Many archaeological sites are in park-like environments — they can be pleasant to visit. People bring picnics and play games and turn it into a family outing, cheerfully oblivious or simply enjoying that, once upon a time, intrigue and pageantry inhabited the spot. They might nibble on their appetizers where soldiers once massed, kings spoke to their subjects, merchants contemplated perilous and long journeys, and captives were sacrificed.

While ruins remind us how much we have forgotten, they also give us license to dream. We can try to imagine what buildings once looked like, what a square full of people might have sounded like, what the market might have smelled like packed with vendors and all the wealth of their wares. Ruins expose us to cultures we might not have known existed, to history we can look forward to learning, to discovering more about the people who probably never entertained the thought that one day we would be standing here wondering who they were.

We think of ruins as being isolated cultural sites, but our effect on the earth has been so significant that we have entered the Anthropocene Era. Sometimes we deceive ourselves into thinking that these changes have been utterly natural, but we are living in the ruins of a natural disaster of our own making, a process started thousands of years ago but accelerating quickly. “Nature is not a temple, but a ruin,” writes J.B. MacKinnon in The Once and Future World: Nature as It Was, as It Is, as It Could Be. “A beautiful ruin, but a ruin all the same.”

Just as Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote about impermanence in his sonnet “Ozymandias,” and later Robinson Jeffers in his poem “Hands,” we should realize that one day someone will stand where we now live and wonder who we were.

Photographer Macduff Everton wrote The Modern Maya (UT Press) and collaborated with Linda Schele and Peter Mathews on The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs (Scribner). For more, visit macduffeverton.com.

This article is featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Sans Souci, Haiti: Built between 1810 and 1813, the ruins of the royal palace of King Christophe (Henry I) are now a National History Park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Copyright © Macduff Everton. All rights reserved.